Three Falcons Players Died Off the Field in the Late ’80s. Could Their Old Teammates Help Me With My Own Loss?

When I moved back to Atlanta, in 2016, I found myself in a dark wood—specifically, Wesley Woods, the psychiatric hospital at Emory University. Insomnia. Suicidal ideation. At 2 a.m. on Sept. 3, I was buzzed into the dimly lit second floor as a Congolese nurse with bright beads at the end of her braids guided me to Room 15.

“Breakfast is at 7:30. The doctor will see you shortly. All is in God’s hands.”

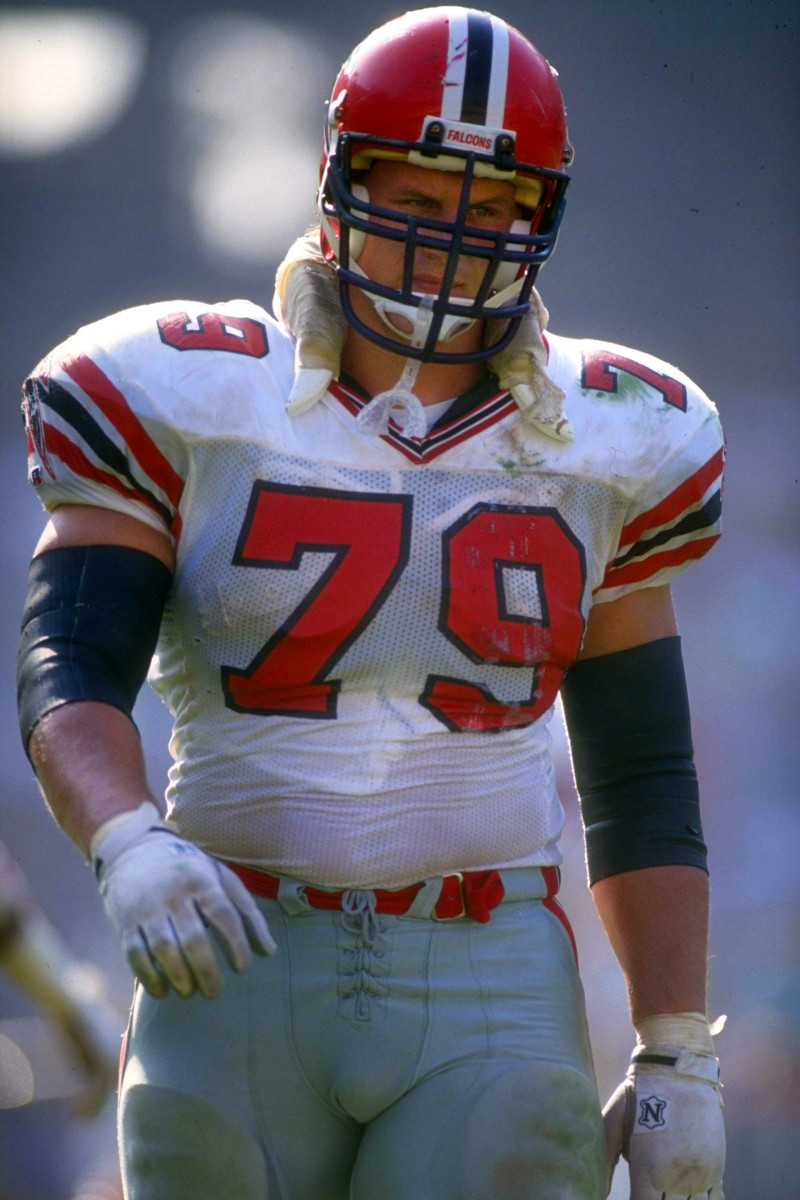

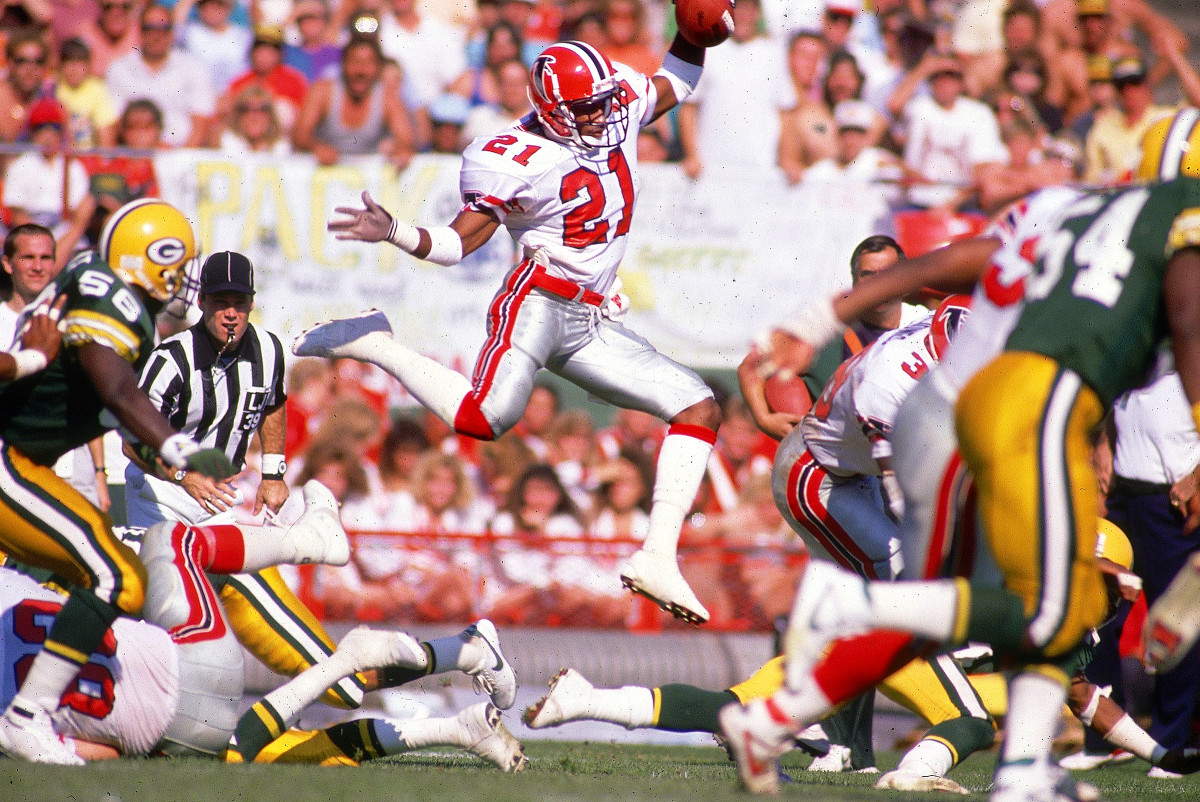

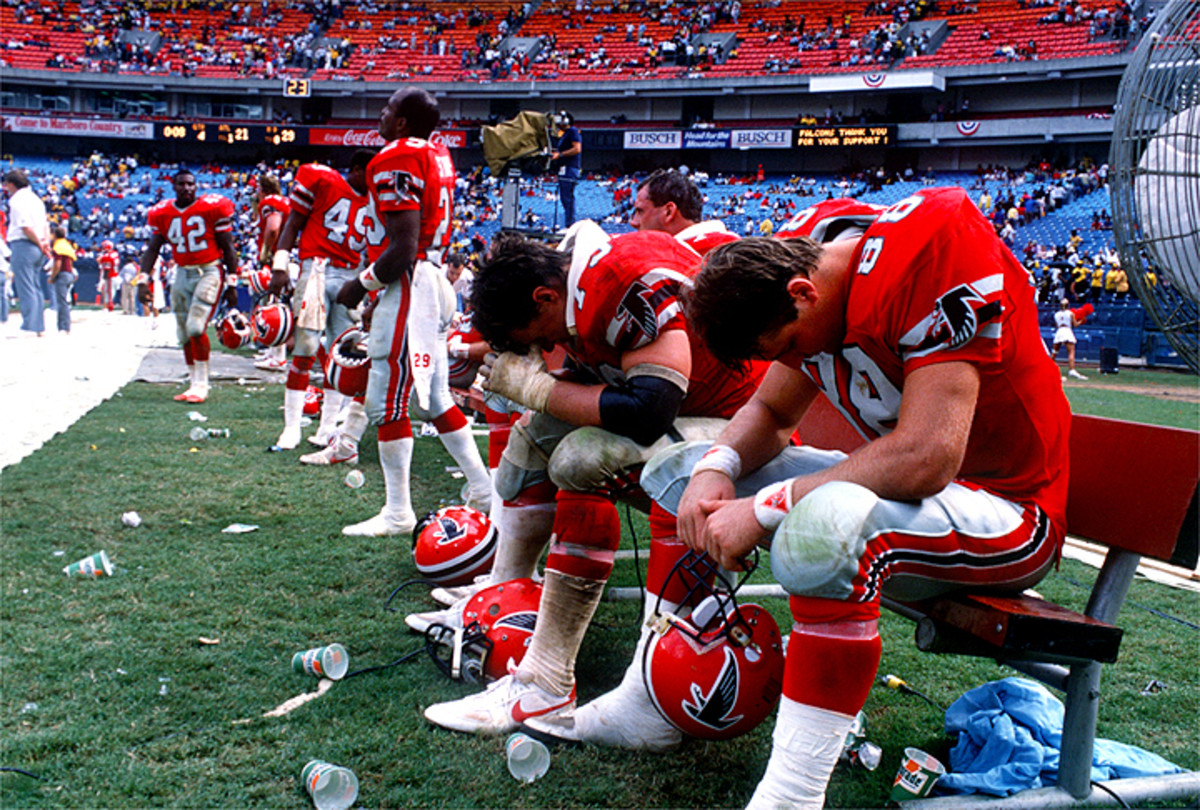

I was six days away from 40. My wife, Alice, and our two daughters were asleep at my parents’ home, but I wasn’t thinking of them. That night I recalled the 1989 Atlanta Falcons. Deion Sanders, No. 21. Bill Fralic, 79. Tim Green, 99. We lost nail-biters; we blew leads and got blown out. To fall in love with those Falcons, as I did at age 13, was to find love below rock bottom. No NFL franchise had ever suffered the deaths of three active players in such proximity: Between October ’88 and December ’89, David Croudip, Ralph Norwood and Brad Beckman all perished.

The funereal Christmas Eve finale against the Lions was my first NFL game. Official attendance at Fulton County Stadium was recorded at 7,792, but that’s impossible. We were fewer. Arctic air had settled across the Southeast. We wore ski masks, Santa caps and brown paper sacks. Bundled in flannel and Army-surplus blankets, we migrated with the sun around the stadium. At halftime, large chunks of us simply drifted away.

Those of us who stayed wanted to see Deion. In the opener against the Rams, in September, he’d returned a first-quarter punt 68 mercurial yards for a touchdown. Swarmed by would-be tacklers, Sanders dropped the ball, recovered it, Houdinied, reversed field and then whoosh. He high-stepped 30 yards into the end zone, each stride sending electric currents clean through our chests.

Who is this? What was that? Were we allowed, as Falcons fans, to … hope?

“Breathtaking,” veteran Atlanta newspaper columnist Mark Bradley recalls on the phone 30-odd years later. “If you saw it, you remember exactly where you were.”

I was in Room 15 when the images from 1989 floated back. As the final gun sounded on that season, I scurried down to the front row and leaned over the sideline railing. The 3–13 Falcons trudged toward their locker room, heads hung. With a Deion rookie card and a black Sharpie in my pocket, I called out to my hobbled heroes. Without breaking stride or looking up, guard Bill Fralic and linebacker Tim Green tossed a red wristband and a white towel, respectively, toward the stands.

Unlike the old Coke commercial where Mean Joe Greene lobs his jersey to a young fan, there was no shared smile. No ambient championship glow. To be a Falcon, to love the Falcons, is to face defeat.

The towel and the wristband float in slow motion, and in the summer of 2020 I reached out to members of those 1989 Falcons. Depression is like living in a house without a roof. Sometimes it's sunny. Sometimes it pours. During the coronavirus pandemic, my skies have kept changing. The acute depression has passed. Quarantine pulled Alice and I closer, our family stronger. But I want to find the Falcons who brought me joy in that joyless season. I want to know how they endured that Sunday and beyond.

“Do you need any help?” the kid with the Coke asked Mean Joe Greene. I wonder that, too. But I’m no kid. I’m a middle-aged Falcons fan who survived a major depressive episode. And as vaccinations stall and the Delta variant spikes, I want the towel and the wristband to linger a little longer.

I didn’t expect Tim Green’s reply to arrive so quickly, but I should’ve. As an English teacher, I’m a veteran of the Scholastic Book Fair, where his young-adult book titles arrive in minted stacks. Green, at 57, is a prolific writer; he’s also an ALS patient. Life expectancy after an ALS diagnosis is two to five years. Green is in Year 3. “Oh, that was a miserable season, Jeremy!” he writes. “I remember it well.”

It’s a season that Green and I revisit over email. We write back and forth like former English majors. We write until 1989 becomes almost the present.

December 24, 1989; 10:17 a.m. (give or take)

Tim Green glances into his rearview mirror on I-85. Atlanta’s early-morning Autobahn is empty, but he resists the urge to open up his red Mazda RX7. The car was his first purchase on his rookie contract. At midnight, that deal expires. The seat belt across his chest tightens. In Week 10, against the 49ers, Green ruptured his clavicle. The bone bulges now against his chest. When he laughs, sneezes, shifts in his sleep, Green feels the force of football’s first and final word.

Green speeds under Spaghetti Junction, a tangle of highways. By day’s end, he and his wife, Illyssa, will be home with his family in New York. Their first Christmas. Illyssa is six months pregnant. Green, who was adopted as an infant, has never looked into the eyes of a blood relative. The pain lifts.

The skyline of Atlanta looms. In the passenger’s seat sits a dog-eared copy of Crime and Punishment. Since his days as a high school wrestling state champion, through his All-America football career at Syracuse and into the NFL, as a first-round pick in 1986, Green’s pregame ritual is to read. Reading settles him. In the locker room he stands out, but he welcomes it.

What do people fear most? the novel’s hero, Raskolnikov, asks. A new step, a new word.

In team meetings, Green sketches out scenes for novels in the margins of his playbook. During summers, back in Syracuse, he shows drafts to his friend and mentor Tobias Wolff. Late at night, at his desk, he reshapes paragraphs. He has carved out a writing life, but he’s not ready for his NFL dream to end.

The RX7 cruises past The Varsity and past Georgia Tech. In college, Green skirted injury, but each NFL season has been sacked. A torn calf. Busted knee. Cracked neck. Concussions. His head swells so much that he often cakes his hair with Vaseline so that later he can remove his helmet.

Being a Falcon has provided Green a crash course in defeat, and in 1989 losing is compounded by loss. Croudip. Norwood. Beckman. In the locker room, after Beckman’s death, players stare past coaches or lock eyes with the floor.

The stadium in view, Green merges right. The cold will magnify the pain. He’s never taken Xylocaine, the liquid-gold nerve blocker that flows through NFL locker rooms. At halftime in San Francisco he begged doctors for the needle, but trainers couldn’t administer the shot. Too close to the heart.

Green pulls into the players’ lot and looks twice. A row of vehicles hitched with U-Hauls. A flotilla of pickups and cars set to flee. A season sunk.

“Do you have a history with depression?” The doctors’ questions in Room 15 at Wesley Woods moved in a circle.

I did. Twenty years earlier. 1996.

“Suicidal ideation?”

Yes. Same time.

“Can you speak about that time?”

“It was the last time I lived here.”

“Here?”

“Atlanta.”

Georgia. On March 21, 1996, my college roommate and best friend, Jason Kenney, died in a drunk-driving accident on St. Simons Island. Jason was driving; I was his passenger. Jason severed his C6–C7 vertebrae; I broke my left foot and sustained a concussion. One of the visitors at the hospital where I recovered was Ryan Patterson, our friend and classmate at Young Harris College. As I slept, Ryan drew on my cast. When I woke, he was strumming his guitar. Fifty-one days later, back at school, in the mountains of north Georgia, Ryan was killed in a head-on collision. His passenger, Stacy Coffey, who sat next to me in communications, also died.

In the summer of 2016, Alice’s mother faced a third major surgery related to a rare and aggressive form of breast cancer. We decided then to move from our home in Boulder, Colo., to Atlanta. A few nights after making that decision, I stopped sleeping and started seeing myself dead or dying, cast in a melodramatic light that I neither welcomed nor understood.

“I was there!” Joe Fralic tells me of that 1989 finale. Joe’s kid brother, Bill—left guard for the Falcons, and before that a two-time Heisman finalist and three-time All-America at Pittsburgh—was wrapping up his fourth straight Pro Bowl season at the time.

I tell Joe: I’m glad to find another soul who was at the stadium that day.

“Well ...” Joe, 62, says from the lumberyard he manages in Huntington, W.V. “I was supposed to be there.” In Joe’s voice I can hear the cadence of Pittsburgh’s vanished mills and the echo of his brother.

Bill Fralic died of cancer on Dec. 13, 2018. He was 56. In obituaries and, back further, in profiles from throughout his career, it’s impossible to read about him without meeting his family. Bill Sr. and Dot Fralic had three sons: Mike, Joe and Billy, in that order. During quarantine, Mike, now 65, spent his days with Dot, 88, outside of Pittsburgh. Both encouraged me to call Joe. “Everybody,” Dot says, “loves Joey.”

Calling Joe from my front yard, a neighbor approaches and asks whether I am using the 5G Network. Do I believe COVID is real? she asks. “Do you find it odd that six feet is the same depth as a grave?”

I call Joe from the backyard.

December 24, 1989; 10:32 a.m.

Joe Fralic peers out the window of his Atlanta hotel room. Growing up in the shadows of Pittsburgh's Edgewater Steel Plant, he knows cold. And this is cold. He’s driven 500 miles with his wife, their 6-year-old daughter and their infant son, all to watch Billy.

As high schoolers, the Fralic boys had bench-pressed blast furnace counterbalances and bulldozed opposing linemen. Mike went on to play at South Carolina, Joe at Marshall. On weekends, Billy, still at Penn Hills High, drove with his dad to watch their games, the highway’s white lines sliding by like so many hash marks.

Bill Sr. was relieved when Billy chose Pitt. His back ached. He refused to fly. Twice, in Korea, he’d been shot from the sky. Two Purple Hearts. But the broken back was courtesy of Edgewater Steel, where he was the president of United Steelworkers Local 1246.

“Don’t forget,” he told Billy before the Falcons took him No. 2 in the 1985 NFL draft, “they’ll toss you to the bone pile.”

Indeed, in that Niners game, Week 10 of 1989, Fralic broke his right pinky. Another entry in a swollen medical file. At age 11 he’d shattered his left arm. The bone never healed. In his first NFL game he pinched nerves in his neck. By the end of the ’89 season he could barely lift his left arm.

On playing with pain, he once told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, “You have to be able to stand outside yourself as an observer.” After games, though, such distance wasn’t possible. In the locker room, teammate Mike Kenn would help Fralic peel the left elbow brace from his flesh, like melted tread from a tire.

Joe knows Billy’s pain. And he feels the cloud hanging over the Falcons. Croudip. Norwood. Beckman. An echo of his college days. In 1970, Marshall suffered an unimaginable tragedy: the crash of Southern Airways Flight 932 and the deaths of 75 people tied to the football program. Seven years later, when Joe played there, the loss lingered.

In Atlanta, Joe studies the bone-white cold and looks back to his kids bundled in bed. No need to turn them into popsicles. It’s Christmas Eve. It’s freezing. They could be back in West Virginia as night falls. Billy would understand.

Back at Billy’s home, no trophies or plaques or gridiron photographs adorn the walls. Once, Joe spotted a pill bottle sitting in a windowsill, something thick inside. He asked Billy what it was. “Drywall?”

A pause.

“That’s part of my knee.”

The house stayed silent.

“A reminder,” Billy said.

I barely touched breakfast and stayed in Room 15 for lunch. After dinner, on the common-room sofa, Harold, a Black guy with wire rim glasses and white, speckled beard, sat down next to me. He wore the light-blue gown and flip-flops handed out at intake. (Harold was not his real name; I’ve changed it here for privacy.)

“Got a sec?” he asked.

I nodded.

“We’re here, right?” he asked. “And you don’t want to be here.”

I shifted in my seat and shook my head.

“Good,” he said, “but to get out, you gotta come out. Each morning, sit right here. See and be seen. You with me? That’s step one. Steps two, three, four and out the door: right up there.”

He nodded to the daily schedule on the dry-erase board: Group Exercise. Group Circle. Outside Option.

“Go to groups. Be on time; they take roll. After groups, play cards. Out here. You like books? Read here. At meals, clean your plate. They check that, too. You get points.”

I nodded.

“And get outside to that courtyard. Listen to the birdies. Watch the clouds. And when the doctors ask, the answer is: stronger. Always. Got that?”

“Stronger.”

“How much stronger, Jeremy?”

“A little stronger every day.”

“Atta boy.”

The nurse announced lights out. Harold stood, straightened his gown and walked back to Room 18. At breakfast the next morning, I wolfed down Corn Flakes, two boiled eggs and buttered toast. On the sofa I read Jurassic Park. In Group Exercise I performed sun salutations. The stale potato salad and tomato soup were no match for me at lunch. In Group Circle I shared Fears and Hopes. At dinner I gobbled down a sweet potato, grilled chicken, garden salad and a slice of peach cobbler. All the while, the door to Room 18 remained closed.

Tommy Nobis is the greatest middle linebacker you won’t find in the Hall of Fame. His widow, Lynn, and their daughter, Devon Jackoniski, speculate on why. Nobis’s stats stack up with Dick Butkus’s and Ray Nitzsche’s, both men first-ballot Hall of Famers. But Nobis starred on a dismal Atlanta expansion club, the No. 1 pick out of Texas in their inaugural draft, in 1966, and his brilliance was unable to escape Falcon tar and feather.

Politics play a role, too. How much light will the NFL shine on former stars who openly struggled with CTE? After Nobis’s death in 2017 at age 74, and then his diagnosis, Devon wrote an op-ed about what the disease had taken from her family. The Nobises, once again, did not get a call from the Hall of Fame. Devon doesn’t worry about that, but she does want the world to know what her father faced.

December 24, 1989; 12:38 p.m.

Tommy Nobis settles in next to the scouts in the Fulton County Stadium press box. Forever Mr. Falcon, his official title at this point, in his late 40s, is Atlanta’s director of marketing. He sowed the frozen field below with sweat and sinew, only to harvest broken bones, blown-out knees and a bell that kept ringing.

Nobis surveys the clusters of fans. 10,000? The season had started with a bang. His kids' friends used to shrug when he asked who their favorite Falcon was. Now? Deion! Deion! After the opener, the Falcons beat Dallas in a sellout home victory.

The Falcons lost 11 of the next 13.

As bad as Atlanta had been over the years—just five winning seasons between 1966 and ’89—the game was good to Nobis. His stature allowed him to start the city’s first Special Olympics, as well as the Tommy Nobis Center, a nonprofit job-training and placement center for disabled adults.

Still: all that losing. The Falcons had nearly landed Vince Lombardi to be their first coach, in 1966, but he wanted an ownership share. Instead, they settled for one of his Packers assistants, Norbert Hecker, who sent Nobis and the rookies on a roofless bus to Black Mountain, N.C., where Billy Graham prayed over the team. Divine intervention was needed. Especially for the placekicker, Wade Traynham, a former gravedigger who against the Eagles, in Week 2, planted for the opening kickoff and whiffed.

How long? Lucy asks. All your life, Charlie Brown. All your life.

Nobis missed nothing that first season. Hard-wired to football’s currents and churn, he recorded 294 tackles. Rookie of the Year. Pro Bowl. The Falcons went 3–11.

In 1989? Stuck on three wins again.

Nobis knows how tragedy can strike. His younger brother, Joe, while a sophomore linebacker at Texas, had drowned before the start of the Longhorns’ 1968 season. Tommy, visiting home during the offseason, was in San Antonio at an Andy Williams concert with his parents when UT assistants delivered the news. Croudip. Norwood. Beckman. Three memorials, three funerals. Nobis, in retirement, had greeted each player on their first day of work with a smile and a handshake, just as he did every other Falcon.

On that Christmas Eve, Nobis stares ahead. Where has it all gone wrong?

Before that first season, in 1966, ownership held a write-in contest: pick the team’s nickname. Entries included the Yellow Dogs, Rebels and Goobers. “The Falcon,” wrote Julia Eliot, a school teacher, “is proud and dignified and doesn’t drop its prey.” She could’ve been writing about Nobis, who stood on the sideline that first NFL Sunday in Atlanta. A glorious September day. The stadium packed. Bright-blue sky. As part of the pregame ceremonies, a trainer released a live falcon. The crowd members pointed and shielded their eyes as the bird circled the field, rose higher, soared over the stadium and disappeared.

On May 11, 1996, the evening my friends Ryan and Stacy died, they were on their way to the spring formal at our college. They had invited me to go with them. I declined. They insisted. I almost relented, but I went home to Atlanta for the weekend. Later, at Ryan’s funeral, I sat with Jason’s parents. At Stacy’s, I wondered why, in all of this, I couldn’t cry. For the rest of that summer I drove around Atlanta at night as the world descended upon the city for the Olympics. After a bomb went off in Centennial Park, killing two people, I waited for the next blast. This is my Atlanta. The summer of 1996. Driving through the night in a whirl on the highway. Waiting.

Eventually, running restored a balance to days and nights. Under the moonlight in northern Georgia I ran countless mountain roads. Unlike driving, I propelled the motion. Each step had purpose. Running solved nothing, but everything came into a sharper focus. And for two decades the road kept rising.

After a long trail run, overlooking the Blue Ridge mountains, I asked Alice to marry me. Later, running the sun-kissed trails of Albuquerque and Boulder, the feeling of home expanded.

Living in Atlanta again, the horizon shrank to highway. I had no intrusive memories of my accident. Hotlanta. No flashbacks. The ATL. But background and foreground blurred. The City Too Busy to Hate! Memories competed with memories and crowded out the present. Exhausted, sleep escaped me. Terminus. Marthasville. The End. The feeling wasn’t like drowning. I’d drowned already, and there at the surface I watched the motions of someone else’s life.

Before dawn, in the shower, I glommed onto the wall. During lunch, at school, I locked a bathroom stall and slumped to the tile floor. On the first of September, I got up for work and collapsed. “You need help,” Alice said. “Now,” she said. “Please,” she said.

December 24, 1989; 12:47 p.m.

We scan the sidelines for No. 21. Deion was listed as probable before the game—a sprained shoulder from the week earlier. But our search is in vain. Deion will not play. Even in disappointment, we’re unable to shake the memory of the season opener, in September.

On that day, Rams punter Chris Hatcher received the snap and whipsawed his right leg. Boom. The ball soared skyward, spinning rapidly as if determined to orbit.

Sanders went on to play the role of a lifetime. Prime Time. As a reality TV star, he was always in character. A Hall of Famer, he adorned his bust with a durag. He opened a charter school. He took a job coaching Jackson State and in the press conference after the first game reported his jewelry missing. He appeared on Celebrity Family Feud.

Name a two-sport professional athlete in American sports history ...

He starred in a Super Bowl and a World Series. He was a Yankee, Brave, Red, Giant. … With Atlanta, in 1992, he led the National League in triples. Deep into that year’s World Series, against the Blue Jays, he conjured the ghosts of Cobb and Jackie and hit .533 with five stolen bases. Earlier in that season, a local prophet hung a banner in the outfield: DEION, THIS IS YOUR BRAIN, alongside a picture of a baseball. And THIS IS YOUR BRAIN ON DRUGS, with a football.

Deion caught flak over breaking the unwritten rules of America’s pastime. He wrote new ones. To unwind, he fished. The charter school closed in scandal. His missing jewelry: found. Team Sanders beat the Kardashians/Jenners by 34 points. Survey says ...

Hatcher’s ball hung midair as if it might claim a permanent spot of sky.

Humility? They don’t pay anyone to be humble. Football? Baseball? Both. Offense? Defense? Yes. A 49er and a Cowboy. He played for Baltimore and D.C. He scolded players who were suing the NFL over its concussion coverup … while filing a worker’s comp claim himself, for injuries suffered on the field. As part of his filing, a team of doctors found him to be 86% disabled. In 1999 he returned a punt 70 yards for a touchdown while concussed.

Several times he attempted suicide, but he detailed only one instance. Summer. 1997. Just across the banks of the Ohio River from Cincinnati, on Interstate 71. He punched the accelerator of his red Mercedes and free-fell 40 feet through the dark. Two days later, he went 1-for-4 against the Cubs.

Red-hot, like an object with wings, Hatcher’s ball plunged toward the earth. “Were you nervous?” reporters would ask him after the game. “Any butterflies?”

“Butterflies?” he’d say. “No, I had buzzards flying around in there.”

Around 2 p.m. on Sept. 10, 1989, East German guards patrolled the watchtowers of Potsdamer Platz. The Cosby Show topped the Nielsen ratings. Prime neared Time. Ralph Norwood watched from the sideline as Brad Beckman sprinted downfield to block. Under the football floated Deion Sanders.

Run to daylight?

Be daylight.

“It could be worse,” Harold said, breaking our silence in the courtyard. I waited for the punch line, but he went back to his Sudoku.

I doodled in the margins of a crossword. My daughter Rose was celebrating her fifth birthday, 21 miles away. Her younger sister, Grace, was about to turn 2. The guilt was immense. Alice didn’t think it would be a good idea to call. I agreed. A rare break from our fights that summer.

I had put Alice in an impossible place. We accepted teaching jobs in Atlanta and our house in Boulder was set to sell when I said: “I can’t go back.”

“That's not logical,” she said.

She was right, but I wasn’t wrong. When she visited Room 15 in a pink dress, we stared out the window, speechless. Months later, when she wore the dress again, I told her I hated it. She said she hated my everyday gray sweatpants. “Fine,” I said. “Fine,” she said. We separately hate-donated the offending garments to Goodwill. But that night, on the phone, Alice’s voice sounded wearier than my companions’ in Group Circle. The party was fine, she said. Paw Patrol balloons. Cake and candles. Ice cream.

Rose had fun, Alice said. Really, she said. “She didn’t even know you weren’t there.”

December 24, 1989; 1:04 p.m.

Tommy Nobis leans forward, hands together, like a prayer. Bill Fralic, right hand clubbed, watches his breath fog. Surreal, Tim Green thinks. A game without fans. The quiet is extraordinary. He catches bits of conversations floating down from the stands.

Mist pours from the face masks of the backs and receivers who orbit the planetary linemen. Next to the sideline heaters a few Falcons hold their helmets at their hips. The wind swirls and Styrofoam cups bob over acres of mostly empty seats.

The billboards under the lights anchor the empty stadium. Enjoy Coca-Cola. Minolta. Bud: King of Beers. The Marlboro Man in left-center field gazes from his post. I blink at him. I blink at the desolate stands, the frozen field. I do this several times. A nervous tick. The Bible lessons at my evangelical school are big on The End. In the twinkling of an eye, at the last trumpet … the dead will be raised imperishable.

Stitched to the shoulder of every Falcons jersey is a black patch with the numbers of the fallen.

The demise of David Croudip on Oct. 11, 1988, didn’t add up. Father to a 3-year old girl, the 5' 8" health nut and former Marine had mastered the roster’s razor edge through kamikaze special teams play. A teetotaler, Croudip refused even fast food. But after a loss to the Rams he overdosed on a solitary late-night drink of apple juice and cocaine. It later emerged that Croudip had sought counseling for depression. His medical history records no concussions, but his sister, Frieda, remembered telling her kid brother to stop leading with his head. A wounded brain seeks relief. Cocaine, like a shot of espresso, ignites a cardiac surge that kick-starts cerebral blood flow. A bump. A pick-me-up. Croudip was 29.

Ralph Norwood was 23, a rookie, when he plowed his Nissan 300-ZX into a tree on the day after Thanksgiving 1989. Investigators said that the offensive tackle, a second-round pick from LSU, had fallen asleep at the wheel. The night before he was found, his fiancé, Kim Anderson, was worried. Norwood had called her at home in Baton Rouge five or six times a day around the holiday—he’d wanted news about their 3-year-old daughter, Ashlee, and updates on their wedding, planned for the coming June. Without word from him, though, Kim went to her job at the post office that morning uneasy.

Not even a month later, on Dec. 18, journeyman tight end and special teams ace Brad Beckman was in the back seat of a Toyota Supra that was crushed by a tractor trailer on icy I-85. He would have celebrated his 25th birthday in two weeks. A memorial service was held on Wednesday. On Sunday, I took my seat on the 30-yard line as the Falcons kicked off against the Lions.

After the game, reporters asked Fralic to describe the season. “Just calling it bad doesn't even come close,” he said. “Somebody will have to invent a new word.”

The airplane cruises at 35,000 feet as Tim and Illyssa Green rest. A white Christmas in New York awaits. Due to the extreme cold, two Exxon storage tanks in Baton Rouge ignited and exploded around 1:30 p.m. on Sunday. Joe Fralic, meanwhile, rides the curved highway along the spine of the Blue Ridge. Two workers were killed. Back in Atlanta, Bill and his fiancé, Susan, search for a place to eat. Another was thrown airborne against a sheet-metal building. Tommy Nobis drives past plastic wise men and front-yard Santas en route to homemade enchiladas and tamales and a candlelight service at Mount Zion Methodist. The fire roared all night. Harnessed to a game without end, Nobis thrashes in his sleep. Once he accidentally hammered Lynn right on the nose. At 10 p.m. across the U.S., It’s a Wonderful Life begins. Kim Anderson, who was home in Baton Rouge stirring pecan candy when the blast went off, lies with Ashlee—her baby, their child—until Ashlee falls asleep. A pink, electric Barbie car, a gift from her Daddy, sits near the tree. Check your local listings. In Tim Green’s luggage, in the epilogue of Crime and Punishment, Raskolnikov dreams of a virus that floats free of the page and into today:

He had dreamed that the whole world was doomed to fall victim to some terrible, as yet unknown and unseen pestilence spreading to Europe from the depths of Asia. ... Entire settlements, entire cities and nations would be infected and go mad. Everyone became anxious, and no one understood anyone else; each thought the truth was contained in himself alone, and suffered looking at others, beat his breast, wept, and wrung his hands. They did not know whom or how to judge, could not agree on what to regard as evil, what as good.

Sheltering in place, Tim Green’s days begin with sunshine. He wakes with Illyssa in their home on the shores of Skaneateles Lake, all five of their children home. Each morning their son Troy brings his own daughter, Thea, all of 16 months, into the bedroom.

“Poppa!” she calls.

Tim and Thea steal moments together. Thea doesn’t know that ALS impairs Tim’s movement, or that exposure to COVID-19 could ravish his immune system. Thea doesn’t know that there’s no cure for ALS, or what those three letters mean. She knows that she wants Poppa's phone.

She points and says, “Pease!”

Tim slides over his phone and watches Thea play.

Thea points to the TV remote. “Pease!”

He passes the remote. The indulgent grandpa. Already yielding.

Downstairs in his wheelchair, with family close, Green settles in for another day of quarantine. Downtown Syracuse is deserted. Pigeons swarm Times Square. America has stopped, not unlike the way time moves with ALS, in rapid slow motion.

Beating the odds is not new to Green. He retired from the NFL in 1993, when he was 30, and published his first book the same year. He’s written 38 more since then, including memoirs on the search for his biological mother and on life in the NFL. But he truly found his voice (and the New York Times bestseller list) with his young-adult sports series.

Between books Green practiced law; worked as an NFL broadcaster on Fox and a correspondent on NPR and hosted a reality TV show; operated real estate holdings; coached youth and high school sports; and spoke in hundreds of gyms and libraries across the country. He misses the kids. Their questions and energy.

“Like everything else I miss, I don't pine for it, but rather cherish the memories,” he emails. “And who knows? They may find a cure for this damned disease one day and I'll be back on the road!”

An eternal optimist whose favorite author remains Dickens, Green knows the fight he faces. “I am pretty far along,” he writes. “Although I can still move my arms and legs, they are weak. My hands barely work, and my feet are completely gone.”

As football delays its reckoning with CTE, ALS presents a different set of questions. CTE’s victims often look fine even while the brain is being strangled by a cascade of neurological chain reactions. The brain of an ALS patient can remain crystalline, but the disease’s erasure of nerve cells and motor skills unfolds before us in real time. From a wheelchair, Stephen Hawking traversed black holes. Lou Gehrig shuffled to the microphone at Yankee Stadium to deliver sport’s finest speech from memory.

Green revealed his own bad break on Nov. 18, 2018, on 60 Minutes. Three years later, he still has no doubt that head trauma endured from football is responsible. Yet football, for him, is still a place of magic. A magic so strong that he stands by his assertion that players would accept the trade-off: 20 years from their life to play in the NFL.

Since his announcement, Green has raised over $4 million for ALS research. In September 2019, Syracuse retired his no. 72 jersey, at halftime of a game against Clemson. Some 50,000 fans roared. Surrounded by his family, Green waved. Now, at home, he is still surrounded. “I try to walk a little every day with a walker and both my oldest boys on either side of me to prevent a fall.”

Until there’s a cure, Tim Green has work to do. The writing calls.

Green completed his last novel by typing just on his phone. Now, for his next book, he uses optical tracking technology. He writes on a wide computer screen using his eyes, a Gaze Point cursor allowing him to shape the text. The pace has slowed, but the pages fill by subtle and discreet shifts in focus. Green travels where the characters take him. Just as always. One word at a time.

Bill Fralic did not want anyone other than his wife to touch him, but Susan already knew that. She wouldn’t hire an RN. She would administer shots. She would research every treatment option for bile duct cancer. She was a daughter of the mills—Allegheny Ludlum Steel—with several semesters of nursing school and a lifetime of loving her husband.

Who else was going to write letters to the Japanese pharmaceutical company asking for extended dosages of trial treatments? Who else was going to trade texts with the doctor at the cancer center in Houston? Who else was going to pray: Please keep him here. Put this in my body, so he can stay.

When Fralic was first diagnosed, in July 2017, doctors gave him six months—but he’d already told Susan long before that: He didn’t suspect he’d live a long life. Even so, he took the long view. During the lost season of 1989 he began working in insurance. He started his own company, specializing in underwriting for interstate auto-haulers, and in 1993, after eight NFL seasons, he retired. “Football has been my identity for most of my life,” he said at the time. “As football went, so did I. I’d like to think I’ve grown beyond that now.”

The people who meant the most kept coming to Atlanta. Mike and Joe brought Dot. They traded stories about Bill Sr., who died on Memorial Day 2016. The brothers returned six more times. They talked of faith and God and Billy’s soul. When Penn Hills friends and old teammates visited, Susan didn’t allow for talk of treatments or goodbyes. Just stories and ribbing and laughter. After one visit, Bill told Susan, “I want to be here for you—but if this is it for me, I am so grateful for my life.”

A God. Billy. The Bull. Rambo. Rambull. King William.

On the afternoon of Dec. 13, 2018, Susan kissed Bill goodbye. Three years later, when she is asked how she’s doing, she pauses. A year of mourning followed by quarantine—how do you explain the double feeling? Peace and sorrow? Presence and absence?

“It’s unexplainable,” she says, “when you really love somebody, and they are no longer there.”

The service for William P. Fralic was held at St. John’s the Baptist, in Penn Hills. Outside the church, over the Pennsylvania turnpike, across the Bessemer and Lake Erie rail line, around the corner from the volunteer fire department and down Elfort to the end of Lorretta Drive, the tall trees still stand. Between chores and practices, the Fralic brothers once chased each other under this canopy of green. A forest of oak, birch and sycamore still stretches along the Allegheny, up the steep banks and bluffs where deer walk above the city whose three rivers converge.

Harold and I ended each evening at Wesley Woods on the sofa. Over the following year, I’d find myself on many sofas. Once, a therapist suggested we pick up from last time. “You were talking about your mother,” he said. I was? “And your father.” My dad? “How emotionally unavailable they were.” They were? This went on until he realized he had the wrong file. Oops.

Another time, a doctor shared that she, too, had a hard time going back home. “Where’s home?” I asked. “Northern Pakistan,” she said flatly, “in a village controlled by warlords.” Her tone did not suggest: See, it could always be warlords. She stated fact as fact and let me file it away.

Each Sunday, I parked myself on my parents’ oversized sofa in front of the big screen. In Falcons-fan collective memory rest shadowy tales of blown playoff leads to Dallas (in 1978 and ’81) and, more recently, high-definition recollections of a squandered 17-point lead to the 49ers in the 2012 NFC championship game. Hope? I knew better. On the ancient sofa I wanted to be entertained. What fate awaited the 2016 Falcons? 8–8, likely. Wild card? Maybe. A division title? O.K. A historic run through the playoffs? Hey, now. A 28–3 lead against the Patriots late in the third quarter of the Super Bowl?

Charlie Brown approaches the ball. Lucy smiles. Her psychoanalytic fee? A nickel.

Super Bowl victories? That’s the stuff of Disney commercials. Hollywood. Saints and Buccaneers fans. Our divisional neighbors—formerly our friends in lowly expansion—have moved up. We find refuge elsewhere. Take the 1999 NFC championship game win over the Vikings.

In the aftermath, my sisters and I, along with my buddy Big Dave, drove to the Falcons’ facility and were swept up in a wave of 5,000 fans. High fives turned to hugs. Strangers wept. Our Falcons? Our Falcons?! The gate to the practice field was unlocked. We streamed in and danced and roared as the team thanked us from the rooftop of the facility. The Waffle House on the hill nearby glowed yellow and bright.

Later, as we dispersed to the parking lot, a grandfatherly figure with a taciturn smile stood bow-legged on the sidewalk. He nodded to the jubilant fans pouring off the field, his hands in his pockets. His forearms were ropes. His biceps, formidable. A mighty, bald cypress. It was him. The first Falcon. The founding Falcon. Mr. Falcon. Our lone star.

I introduced myself. Tommy Nobis’s hand, an intricate root system, enveloped mine.

“You’ve seen it all, sir. But have you ever seen anything like this?”

Nobis smiled and ruefully shook his head. “Naw,” he said, “this is … something.”

We talked about the game. The comeback. Overtime. A road playoff victory. Our Falcons.

Nobis kept smiling, shaking his head.

“Ever see this many people on the practice field?”

He rubbed his chin and looked out over the darkened green. “You remember the old stadium?”

I told him I did.

“Many of those games didn't have a crowd this big,” he said. We laughed, and I felt the pull of the cold. “But I’ve never seen anything like this.”

I wasn't sure whether to shake hands again or salute, but Nobis beat me to the spot. He winked, slapped my shoulder and said, “Onto the big game.”

We drove home under the stars—the same indifferent stars that shone over Miami two weeks later when the Falcons lost to the Broncos. The same celestial band that dwarfed Houston in 2017 as another Super Bowl slipped away, to the Patriots. During that season, Nobis watched each of Atlanta’s games on TV. Devon sat with him and asked how the Falcons were doing.

“Are the Falcons playing?” he’d ask, confused. When Nobis died on Dec. 13, 2017, the night sky was clear.

A year later, Boston University neuropathologist Ann McKee announced that Nobis’s Stage IV CTE was the most severe case her team had ever seen. The storms that had long raged inside the Nobis home now had a source. For solace, in high school, Devon would run for miles around her neighborhood. Now she knew why her dad blew up so easily at restaurants, in banks and at her own wedding. Now Lynn understood Tommy’s issues with crowds, loud noises, kids. His depression and paranoia—“the Falcons,” he’d say, “are following me”—made sense. Tommy Nobis, a tireless advocate for disabled people, had spent his adulthood disabled.

His family knows that now, but “it wasn’t until after he passed away,” Devon says, “that we realized we didn’t really know who Tommy Nobis was.”

On my last of three nights at Wesley Woods, Harold and I watched a local-news sports report from the Falcons’ preseason practice. Quarterback Matt Ryan was being interviewed.

“Matt’s all right, you know?” Harold said.

“Yeah, Matt’s all right.”

“He’s no Mike Vick.”

“Nope,” I said. “Only one Mike Vick.”

“Mike just flicked that wrist.”

“Mike Vick threw lasers. … You remember Vick in that Vikings game?” I asked.

“The run?”

“When he split two dudes.”

“Swoosh,” Harold said.

We laughed and let the brilliance of Michael Vick float between us.

“Two minutes,” a nurse announced.

Harold sighed as if catching his breath.

“You know,” he said, “there was one greater than Mike Vick.”

Our plane had shifted. The elevation. We were no longer talking quarterbacks.

“Yes,” I said.

“You with me?”

“I am with you.”

Harold shut his eyes, cradled an invisible football, raised it high and pointed.

“Prime,” I said.

Harold smiled and shook his head: “Prime. … Time.”

We laughed and high-fived. The nurse asked us to please stop, please keep it down, but we did not stop and we did not keep it down. We rose up. No longer mere occupants of Rooms 15 and 18, we were two witnesses to the human limits of flight.

The 2020 Falcons botched a simple onside-kick recovery, scored an unintentional touchdown, fired a head coach and suffered a litany of losses that would be inexplicable to any other franchise. Nine times they blew leads, but two of those occasions stand out, each a 15-point fourth-quarter head start wasted—and in back-to-back weeks. (No team has ever lost in this manner twice in one season.)

The first one, against the Cowboys, was spoiled largely by Dak Prescott. In the aftermath, Dallas’s quarterback was mobbed by teammates. A week earlier, Fox commentator Skip Bayless had criticized the QB for sharing his experiences with anxiety, insomnia and depression following the suicide of his brother Jace. Bayless found the comments beneath the “quarterback of America's team.” In a year when 375,000 Americans died from the coronavirus, 27 million lacked health insurance, 30 million were unemployed and 40% of those polled reported negatively altered mental health, Prescott, indeed, stood squarely that Sunday as America’s Quarterback.

In the celebration, Falcons tight end Hayden Hurst sought out Prescott. Hurst, too, has faced depression. He has survived a suicide attempt. And on the field the two embraced. Hurst, who runs a foundation that focuses on mental health issues for veterans and kids, told Prescott that he’d like to work with him someday. Prescott agreed.

The courage of both men is compounded. According to a 2019 study in The American Journal of Sports Medicine, the longer an NFL career, the greater the risk for depression and cognitive decline.

On that frozen Sunday in 1989, the wristband and the towel disappeared into outstretched hands. But the next morning under the Christmas tree sat a game-used Falcons helmet. I picked up the headgear and sank into the sofa. This lid—Bike-brand shell; three-bar cage, plus a vertical bar—was no toy. I ran my hand over the polycarbonate dome and traced the fissures on the crown.

Tommy Nobis and Deion Sanders could only watch that Christmas Eve as Bill Fralic braced himself and Tim Green soared off the edge. Blinking in the stands, I sought an old chaos of the sun. The Marlboro Man, however, never blinked.

Steady, he kept watch. He saw things near and far. The silent witness to our winter spectacle.

Sometimes the voice catches her, and the years collapse around Lynn Nobis. She’s back in Austin with Tommy. Willie Nelson is playing for Coach Royal at the Villa Capri Motel. Tommy watches Willie’s fingers on the frets.

Now, sitting alone in her parked car, Lynn closes her eyes as Willie sings:

Life goes on and on

And when it's gone

It lives in someone new

It's not somethin' you get over

But it's somethin' you get through

At the Tommy Nobis Center in Atlanta, clients who navigate cerebral palsy, Asperger’s and Deafness—masked and socially distant—prepare PPE kits on the assembly lines of the 39,000-square-foot warehouse and load them onto trucks, to be delivered across Georgia.

In Pittsburgh, Mike and Dot and Joe Fralic play cards. Before quarantine, they’d all go to Rivers Casino. A hot hand, Dot knows when to fold ’em. She has her limit: $100. The secret, she says, is to never go below that. Once, at the slots, Joe spotted her dip past that mark. “Whatcha doing, mom?” he asked. “Well,” she said, pulling the lever, “I’m no quitter.”

In Baton Rouge, Kim Anderson walks her postal route. After her fiancé’s death she took a sorting job inside—but after five years she went back out to deliver, and she’s been walking her route ever since, making more friends than she can count. During the pandemic, waves replace hugs, but she feels the smiles. On sunny days, she takes her lunch into the shade of a pecan tree.

Sometimes Devon will walk by her son’s room as he strums his guitar, the chord progression moving from D to G: Out in Luckenbach, Texas, ain't nobody feeling no pain.

Five times Susan Fralic has had the same dream. Bill appears in the background. Which is odd. Not like Bill. Just blending in on the edges. But there he is, smiling.

Ashlee Norwood is now Ashlee Noel, with three boys of her own. She teaches 11th Grade U.S. history and African American studies at Humble High in Houston, where she tells her students, “Always ask hard questions.” In her closet, next to her graduation gown and a kente cloth, hangs her father's red Falcons jersey.

Tim Green and I exchange 100 emails over the summer. I share a few details about my depression. Tim listens, encourages. We also talk about coaching our kids in youth sports. I share pictures of my daughter’s U-5 and U-8 soccer teams, the Iron Puppies and the Fire Unicorns. He tells me about his daughter’s college lacrosse season. We detail the pleasures of reading with our children and rattle off the books we savor. Sometimes we talk about the weather.

When the weather is nice, Tim goes outside with his family, where he’s “keenly aware of God’s gifts.” A colony of swallows nest in boxes across his yard. Orange orioles call from the treetops. Yellow warblers, red cardinals and hummingbirds join in. “I often close my eyes and enjoy the symphony of calls,” he writes. “Occasionally, ospreys and bald eagles will cruise the shoreline from high above.”

For the rest of that summer, on my three-mile run, birdsong bounces at dawn from pine to dogwood. Up and down our hilly metro Atlanta neighborhood, I run past yard signs: Everything Will Be O.K. … A Frontline Hero Lives Here. My pace quickens as I scan the tree line and savor gratitude’s sharp sting.

When I was a kid, a sad-sack football team gave shape to every Sunday. What I needed from the Falcons in 1989—a modest win streak—they couldn’t provide. Years later, they gave more. And in the evenings after dinner, I walk with Alice, Rose and Grace, and I watch the patchwork of sky for all that is there and all that is not.

• Tear Gas and 'Melancholia': Argentina Can't Let Go of Maradona

• How the Failed Super League Exacerbated the Fan-Owner Dynamic

• He's Old-School. He Doesn't Do Analytics. And He's Thriving in Today's MLB.