Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

Dak Prescott rises from the wooden table in his kitchen. It’s June, and he’s standing at a pivot point—far enough past the worst stretch to look back but not that removed, either. He strolls down the hallway to his office, returning with a single sheet of notebook paper that he saved for more than a year but has shown only to his girlfriend. The words are blue, the handwriting tidy. He holds the paper delicately by the top corners.

Jace MacKenzie Prescott

A Life Taken to Save Millions

You’ll never be forgotten for one second.

-Why didn’t you ask me for help?

-Did you tell someone how bad you hurting?

-Do you know how many people you affected?

-Do you know you’re adored, admired, loved?

Prescott wrote those sentences on April 23, 2020, the day he’ll always remember but would give anything to forget. The night before, after weeks filled with anxiety and depression, not to mention a contract saga that dragged on without end, he slept soundly for the first time in forever. He woke up after 8 a.m. to his father and friends standing in his bedroom with red eyes and anguished faces. His phone looked like a slot machine, pinging and flashing with hundreds of missed calls and unanswered texts.

• Get the football preview issue featuring our Dak Prescott cover story here.

A few hours earlier, 300 miles away, Dak’s uncle, Phillip Ebarb, had been awoken by a police officer in the middle of the night. The cop said, “I’m here to inform you that your nephew, Jace Prescott, is deceased.”

“What are you talking about?” Ebarb asked. “What do you mean?”

The officer didn’t know what to say. So he said only the truth.

“He took his own life.”

Ebarb screamed, then collapsed. He drifted through the next few hours as if living in someone else’s nightmare. He had to call Jace’s girlfriend, who was waiting outside the hospital, believing her boyfriend was still alive. He had shot himself at their apartment and died soon after.

Dak needed to escape the bedroom, and those anguished, tear-streaked faces. He went outside, by the pool, and when he looked up, he no longer saw the “dark cloud” that had hovered over him. Instead, the sun was blinding. He couldn’t think. He bolted back inside to write the letter, 15 minutes after he found out.

His oldest brother, Tad, immediately flew from Lake Charles, La., to Dallas. But upon arriving at Dak’s home, Tad lingered outside, blaming himself, smoking a cigarette, unable to walk in. When Dak found him out there, Tad could only say, “I’m sorry.”

“Don’t apologize,” Dak told him.

So they started telling stories, looking back, attempting to make sense of what did not and probably never will. Introversion was Jace’s default setting. He didn’t talk much about his feelings. Dak had checked on him about a week earlier. “This is my life,” Jace responded.

Dak’s thoughts spun in a thousand different directions. To Nathaniel, his father, who had to tell him his mom died in 2013, meaning Nat had delivered the worst possible news twice. To Tad, whose last promise to his dying mother was that he would care for his younger brothers, always; who had forgotten to message Jace to meet up that April and would be haunted by the text that slipped his mind. And to Jace, not only for the life they shared but for what had now become unfathomably clear—what they didn’t.

Even then, something unexpected happened. Deep into his worst 18 months ever—those miserable, universe-questioning, transformative months—Dak gleaned important wisdom that he would carry into the 2021 season. Just thinking about others, their pain, helped him to deal with his own.

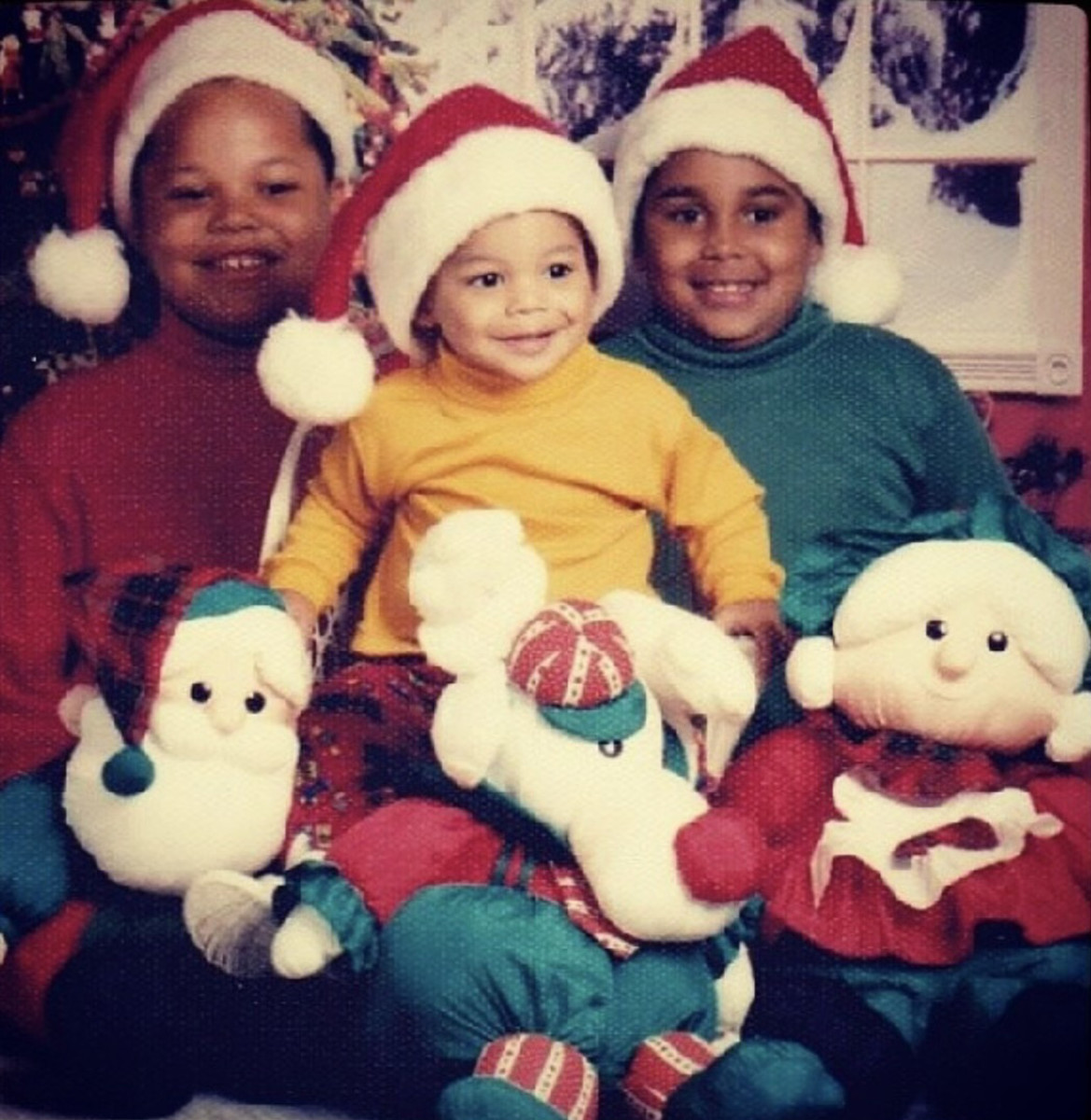

Fourteen months after that terrible day, Prescott arrives early at a cigar bar near the Cowboys’ headquarters in Frisco, Texas. He’s alone—no entourage, no reps. Early into a nearly three-hour sit-down, he grabs a legal pad and begins to draw the first and most important home field of his life. He sketches the sliver of a yard in northeast Louisiana; draws his older brothers’ bedrooms; outlines the living room/bar/kitchen and the room he shared with his mother, Peggy.

His eyes dance as he scrawls, the memories returning. Someone put a hole in that wall trying to kill a spider with a hammer. There were scratches all over that door from a few thousand too many Nerf dunks.

For a household that moved around and spent more than a few nights without any home at all, the trailer park and all the fields nearby made up the only world they ever needed. The one they could create themselves.

Long before fame, even before football, Prescott absorbed an important concept in that single-wide trailer. He can summarize it in one word: manifesting.

Even in a family that turned competing into “almost an illness,” the boys’ aunt/nanny, Valrie Gilbeaux, says the youngest one stood out. For what he wanted. For how his brain worked. Prescott watched the movie Little Giants, over and over, relating to one scene where players reminisced about times they had beaten their brothers. Because that’s exactly what he had wanted since the day Jace handed him a football and said throw. Dak developed a method for speed-eating Oreos, figuring out that if he detached the cookies from the creme rather than shoving the whole thing in his mouth he could actually swallow faster, like a mini-Kobayashi.

He was the dreamer in the family, the one who manifested reality before any sports psychologist deployed that term. He alternately predicted his future as a movie star, football All Pro or President of the United States.

“Everything in my life [that happened], I’ve constantly thought about,” he says. “Of saying things, believing things, working, then watching them come to fruition.”

He wasn’t like the other children. He didn’t want a picture with or an autograph from a famous athlete, because he expected to become one. He kept a Matchbox car, an El Camino, for the day he would drive the real thing. Yet, when Tad complained of the endless rotation of the same meals—chicken, meatloaf, spaghetti—Dak looked at him earnestly and, despite being younger by six years, said, “Bro, I’m just grateful we got something to eat.”

The nearest college football power, LSU, didn’t see Dak as a college quarterback, at least at first. So he went elsewhere, lifting a lackluster Mississippi State program to a No. 1 national ranking. Manifesting. The coach who recruited him, John Hevesy, soon discovered that Prescott’s “leadership skills just overpower you.” Manifesting. He switched majors to psychology, because he wanted to coach, and he hoped to better understand the psyche of future players. Manifesting. Prescott would lead the Bulldogs into Tiger Stadium, then topple LSU just as he had decided in his head after the scholarship didn’t come. Manifesting.

His sophomore year at Mississippi State, he showed up at the football facility at 6 a.m. the day before his mom died, telling coaches he must play that afternoon—to sort through his loss, to give meaning to her death. These older men stared back at him, trying to understand how someone could be 20 and 40 at the same time.

Ebarb would take his youngest nephew fishing around then. He wanted to gauge Dak’s mental state in the best way they know how: out on the water, phones shelved. They stopped at a small store in a small town to purchase fishing licenses. All broad shoulders and big smiles, Dak laughed and told jokes.

As they strolled back into the parking lot, four women followed them outside. They wanted to take a picture with Mr. Charming. Ebarb snapped away, before they asked him an odd question. Who, exactly, was his nephew?

“He just projects that vibe,” Uncle Phil says, “that he’s somebody. ”

Ebarb knows exactly where that comes from: “When you have decided what you’re going to be your whole life, it’s just who you are.”

His nephew now lives in North Dallas, on grounds so expansive they could fit a small trailer park in the backyard. His estate—pool, football field, pond, golf green, fishing creek—unspools over seven acres, because that’s the exact size he dreamt of as a child. There’s an El Camino parked in the garage. It’s near the Ferrari with the personalized license plate: SINGLEWIDE.

Everything from the layout of the property to the activities Dak partakes in speaks to the duality he created. He took the place he loved the most and made himself a larger, fancier, upgraded version. In some ways, everything is different now; in others, nothing is.

He laughs. The mind sure is a funny place.

As Prescott ascended throughout his 2016 rookie season, his rise struck many as improbable. But not him. He expected to become one of the NFL’s top quarterbacks, to change the minds that doubted him.

In four seasons, he manifested a new reality, becoming the most important player on the highest-valued team in America’s most popular sport. But that climb created a first-world problem. To retain his services and push to end a championship drought that now stretched over two unacceptable decades, Cowboys owner, Jerry Jones, needed to pay the face of his $5.5-billion franchise the kind of massive contract that either launches teams or ruins them.

Watch the Dallas Cowboys online all season long with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

As negotiations dragged on, the worst thing that could have happened on the field did. On Oct. 11, 2020, Prescott starts his day in a hotel room, buses to the stadium, then watches from the home locker room as his friend Alex Smith completes the most remarkable comeback in NFL history. Smith had jogged back onto the field for the Washington Football Team almost two years after nearly losing his leg from infections that followed a gruesome on-field break. “I got chills,” Prescott says.

Fast forward a few hours. Cowboys-Giants. Third quarter. Prescott goes down on a routine tackle by Logan Ryan. He thinks he rolled an ankle. He leans over and sees his right leg bent sideways, the ankle pointing outward. He hears his mom in that instant, imploring him to get up because that’s how she would know he wasn’t hurt. He tries to bang the ankle back into place, realizes he cannot stand and waves frantically at the sideline, as Smith prays from afar and Jones grimaces in the owner’s box.

A friend had told him years earlier that in times of crisis he should thank God over and over. So as the broadcast team screamed “oh no” … thank you God … as doctors rushed onto the field … thank you God … as teammates patted Prescott on the helmet … thank you God … as the cart drove him away … thank you God … as he buried his tears in a towel … thank you God. “That was my peace in all this,” Prescott says.

The processing began as soon as the cart sped off. Prescott was honest with himself, immediately: His season was over; no need to raise false hope. That’s why the tears ran from his eyes in streams, why he covered his face with a towel. Then, forward. He watched the rest of the Cowboys victory on his phone in the ambulance. He sent a congratulatory message to Andy Dalton, the quarterback who had replaced him. He texted Gilbeaux, the aunt he had spied in a tunnel at the stadium, telling her, “Quit crying; I will be fine, it will be fine.”

Doctors delivered a diagnosis that suggested otherwise: a compound fracture and a dislocation. Because of the type of injury and severity, his break forced an obvious comparison to Smith’s extensive damage.

Tad was upset, and not just about the end of a promising season, but because he had urged Dak to sit out the first six games, in order to make a point in negotiations and remain at full health. “It’s not like I’m gonna get hurt,” Dak told him.

The Cowboys, depleted by injuries and without their star quarterback, would limp through a 6–10 campaign. First, Dak woke up in the hospital. Tad’s thoughts ping-ponged. He knew Dak had overcome far worse, especially that past April. But he also worried the injury might change the Cowboys’ plans.

Not Dak. “What I’ve been through, I’ll call it a callused mind,” he says, describing a broken ankle as “just another scratch that’ll heal up, that’ll make me stronger.” In the months that followed he would sometimes pull up the video of that hit late at night and cringe. But as a nurse wheeled him out of surgery, toward anxious friends and family, Prescott said only two words.

They spoke, as always, to his mindset.

“What’s next?”

Back in the cigar lounge, for the first time in over an hour, Prescott pays cursory attention to the bank of televisions on the opposite wall. Tennis star Naomi Osaka is on the screens. She had withdrawn from the French Open a few days earlier, citing her mental health. To Prescott, her struggle shows that the mind is more than a funny place. It’s also a delicate one.

The quarterback says he never grappled with his psyche—until he did. He remembers looking at others and thinking, “What the hell are you stressed about?” He didn’t understand stress on a baseline level; like as a concept. But that changed in 2018.

Despite a playoff and Pro Bowl season, Prescott spent too much time in the worst place on earth for anyone who wants to feel decent about themselves: Twitter. Outside perceptions began to bother him, and football—really, everything around it—“started getting a little hard.”

He deleted the app from his phone, allowing others to run it for him. But it wasn’t just Twitter; it was everything around football, from celebrity to fame to expectations to outside noise.

Prescott had already met twice with a therapist, who taught him to vent about what bothered him. He needed to in ‘18, and often would to Jace, especially as it related to the noise/perception of the contract. To be clear: It wasn’t an issue in the locker room. The base salary—the one he earned in the final season of a four-year, $2.7-million deal—didn’t offend him, either, not the kid from the single-wide. His annoyance instead centered on how the endless conversation around it affected his off-field focus; he wanted to tunnel into football and let his representatives handle negotiations. But everywhere he went, every news conference he attended, every round of golf he played, every stranger he bumped into—everyone wondered the same thing, for the better part of three years. “Do y’all want me to go crazy?” he sometimes thought, as pundits and strangers, outsiders all, “created a lot of false narratives for who I am and how I think.”

How Dak shapes his thinking is the most relatable thing about him. He’s an elite Google searcher, with no rabbit hole too deep, no topic too farfetched to immerse himself in. In recent months, he looked into the plight of Dallas’s homeless population, Mississippi State’s national champion baseball team and incoming football recruits.

These dives speak to a mind that’s always racing, probing, thinking. But during the global pandemic in 2020, the same endless curiosity started to birth adverse effects. With a more typical, physical injury, there would be goals, day-to-day improvement, therapy, people to lean on, in-person conversations to be had. The pandemic was not that, nor something he could control. He worried about his family contracting COVID-19 and his life as anything other than the Cowboys quarterback. He says he doesn’t believe the contract factored into his growing apprehension, but it’s certainly possible that it did, even on a subconscious level.

“So much anxiety built depression,” he says, before laying out his thought process. Well, now I’m sad. Now, I’m upset. Now, I’ve got these thoughts of: What’s going to happen to me? What legacy do I have? Who am I if I’m just in this room?

Truth is, he had already been anxious. Before the pandemic Prescott took a trip to Los Angeles, renting a place in Newport Beach down the street from Kobe Bryant. In his youth, Prescott had rooted against the legend; over time, he came to idolize the man instead. One night, they both went to dinner, separately, at a nearby steakhouse. Someone asked if Prescott wanted an introduction. He declined, figuring that Bryant was busy entertaining his own guests, assuming they’d meet eventually.

A week later, his girlfriend, Natalie Buffett, gasped and handed him her phone. Bryant had died in a helicopter crash. As the couple rode to the airport, they passed by the residence, with dozens of news crews stationed outside a gate lined with balloons, flowers and sympathy cards. Prescott felt a surge of anxiety in that moment, because he saw Bryant as powerful, invincible, young. “It just showed me how close death is,” he says. “That nobody’s safe and all of us have a ticket out, and that’s the reality of this world.”

Prescott loved his seven acres but started to feel confined there, the sprawling estate more like a cell than any trailer, before his brother died. He’s “almost embarrassed” to say that, knowing many had it so much worse. But that didn’t change how it felt when he couldn’t get out of bed, leave his room, or pick up his phone. “Like I was in a box, and I couldn’t get out of the box,” he says. “It felt like sunny days were dark.”

Through Bryant’s death and the start of the pandemic, Prescott did not speak with another counselor. But he did reach out to family members; specifically, his brothers. It was Jace, his “big ol’ teddy bear,” who responded first. “I’m here for you,” he tapped back.

Jace had lived with their mother at the end, watching the cancer wreak its devastation, every day a little worse. He saw her take her last breath. Maybe he worried he had disappointed her, because of what many projected him to be: a star who would play in the NFL. But Jace suffered, too, in part because of the sport he loved. He told relatives that when he fell on one middle school opponent, he could hear the poor kid’s bone snap. He shattered his own wrist, suffered other injuries and didn’t finish college. “Not long after that, [she] passed,” Tad says. The trauma continued piling up. “Just stacks and stacks and stacks.”

Dak never expected any positives would come from his brother’s death. He didn’t want any. But in many ways, if he’s being honest, he believes it steeled him. Losing Jace gave him gifts he would give back, like clarity, the ability to sort through his emotions and sort out his future.

That lucidity helped Prescott map out and maximize his time away. He told doctors he didn’t want to put a timetable on his recovery, because he planned to do as much as possible each day and didn’t want an arbitrary deadline he would inevitably try and beat. “I didn’t care what they said, honestly,” he insists, which is exactly what his aunt remembers his mother saying after the cancer diagnosis.

With no football to play and up to 12 hours a day where his still-healing leg needed to be elevated, Prescott considered himself in a more holistic way. He still had trouble sleeping, which meant more Google searches; deep dives on nutrition that led him to cut out fast food, for instance. He also read more, gleaning recommendations from coaches, teammates and an unexpected source—Ryan, the opponent whose tackle had injured him.

The defensive back sent a handwritten letter and two books that helped him recover from his own season-ending injury (a broken leg) years earlier: Relentless, by Tim Grover; and The Mamba Mentality, by Bryant. The Cowboys mental coach, Chad Bohling, introduced Prescott to other clients, like Derek Jeter. The Yankee great told the quarterback that he had hurried to overcome an ankle injury and wasn’t in full health when he returned. Don’t rush back, the Hall of Famer counseled.

Prescott graduated from crutches to a boot, walking to running—mundane steps he viewed as small injections of “joy,” because he had chosen to look at them that way. Using the same thought process, he elected to undergo a second surgery, to stabilize the ankle and avoid another procedure in later years. Sure, this pushed his recovery out a couple weeks. But he elected to see it as potentially gaining back months in a later off-season.

He started golfing more, because he liked the solitude, the way he competed only against himself. He took up tennis for the same reason, because “you think it’s you vs. the other person, and it’s not. It’s you vs. the net, you vs. the backline.” These, too, were mental reps.

For months, this practice extended way beyond football. Prescott devoted extra time to numerous off-field causes: raising money for a cancer research grant in his mother’s honor, donating $1 million to police training, partnering with three mental health organizations, sponsoring after-school programs. He donated a thousand meals for the homeless. He also wrote to politicians on behalf of a prisoner, Julius Jones, who he believed was wrongfully incarcerated for murder.

The point to all of this was to become a more complete person, in an authentic way. Combat homelessness because he himself had been without a home. “It wasn’t just for football,” he says. “And because I love football, and football has been easy, it allows me to love it even more.”

Ultimately, Prescott does not consider his 2020 season “lost.” He believes surviving the physical and mental gauntlet will allow him to play for another 15, 20 years, if he desires and can stay healthy. His mindset was reinforced by a random interaction in a restaurant, when a little girl approached his table and asked if she could show him a picture. On her phone, there was a chihuahua, cute but with legs turned outward like Prescott’s on the day of his injury. She had fostered the puppy because of him. “His feet are on backwards just like yours were,” she said. Her thought process, the framework especially, stunned him. He knew then something else: The mind is a funny and delicate place—but also a beautiful one.

On the day of that injury, despite the nausea and the headache, Jones rushed to the locker room to see Prescott before he left for the hospital. The owner wanted to hug him, to tell him they’d get through it. But he had a more important point to convey first, even if he knew it best not to discuss figures: He needed Prescott to know the Cowboys still wanted to sign him.

The quarterback says he always expected to stay in Dallas, although it’s easy—and practical—to say that now. But it’s one thing to believe it and another to sign one of the richest deals in sports history, a notion highlighted by the machinations in negotiations. In 2019, before the Cowboys applied the franchise tag to Prescott, both he and Jones left a scrimmage against the Rams in Hawaii believing they had all but agreed to terms. Cowboys legend Troy Aikman, then broadcasting the Cowboys opener, was told that Prescott might put signature to paper before kickoff. But the sides simply ran out of time.

Still, Jones recognized the value in his quarterback. He cites the authenticity, the “human element” of Prescott’s leadership, the mindfulness unlike any he has “ever seen.” Then he adds availability, nodding to Tony Romo and his injuries. Jones says his biggest regret in his decades in pro football is not winning a Super Bowl with Romo behind center. In Prescott, he sees many of Romo’s best traits. “It’s called makeup,” Jones says. “At every step, he has over-delivered. I heard him talk about ‘generational wealth.’ He was always a generational thought in my mind [as a Dallas Cowboy].”

Michael Irvin remembers a night out with Stephen Jones, Jerry’s son and the Cowboys director of player personnel, at a Super Bowl a few years back. Over cocktails, Irvin says Stephen told him that “one day I’m going to write a check for about $200 million” to Prescott. At first, Irvin balked, thinking Stephen was overestimating how high the cost of franchise quarterbacks would rise. But negotiations stalled long enough for that estimate to be right.

Still, Prescott ignored the delay as best he could. He instructed relatives not to bring it up. He told his girlfriend he hoped that Dalton “balled out” in his place. When Tad mentioned sitting out in 2020, Prescott said the franchise tag represented a $29 million raise beyond the endorsement income that already allowed for the seven acres and the Ferrari with the personalized plate. This was at least we got something to eat all over again—the same outlook that Prescott says helped him “move forward with happiness” just hours after the broken ankle.

Last February, Prescott and Buffett traveled to Park City, Utah, for a vacation. The quarterback doesn’t ski, so he spent a week staring up at the mountains and into the fire. He felt something odd as the hours flew by. Maybe … relaxation? Calm?

Upon returning to Texas, he decided to check in with his agent. So many “sources” were claiming this and that. He needed to know, from the most direct source of all. He instructed Todd France to text rather than call but France instead buzzed Prescott a few hours later. “Do you love me?” he asked, as both men started laughing.

Eleven months after he lost his brother, five months after the ghastly injury, Prescott inked a four-year extension worth up to $160 million. The more relevant numbers—$126 million guaranteed, $66 million signing bonus—signified how much the Cowboys valued him. Irvin says it will “look small” in the years ahead.

As Tad heard France go over the details, he stopped hearing the agent’s voice. There was a movie playing in his head: the brothers rollerblading around the trailer park, Dak’s signature victories, their mom, Jace. This montage ended with an event that hasn’t happened yet—“me laying on the field with him,” Tad says, “making snow angels of confetti.”

The night he signed, rather than plan a massive celebration, Prescott and Buffett went to an already-scheduled dinner. He can’t remember if anyone made a toast. But she remembers walking in, and every other diner standing up, delivering the man from the single-wide trailer a standing ovation. “It’s amazing that I got hurt and before I ever got on the field again, I was rewarded,” Prescott says. “But that plays a big part in the things I’ve manifested.”

After he tells that story, he points to the red scar that runs for about six inches across his right ankle, forming a wishbone after the second surgery. Same word: mindset.

At the cigar bar on June 1, Prescott presents the antithesis of a football star all but guaranteed nine figures in career earnings. He’s dressed in shorts and a T-shirt, slip-on shoe covering the scar, nothing fancy, no obnoxious branding. He heads to the back room, which is empty, and reclines on a black leather couch.

At that moment, the wall of TVs is tuned to NFL LIVE. The analysts are debating Dak Prescott; specifically, whether he’s ready for the magnitude of what’s in front of him. Briefly, it’s like he’s trapped in a hall of mirrors. That’s his face, his highlights, on something like 20 screens.

This is also life, his, in America’s largest and most scrutinized fishbowl. Prescott knows, because everyone knows, that Dallas has not won the only game that matters to its deep-pocketed owners and rabid fanbase since triumphing in Super Bowl XXX. On that day—Jan. 28, 1996—he was 2 years old.

Ankle healed, mind fortified, Prescott returned this spring, everything different and nothing changed. Before jogging onto the field, he reached for a familiar touchstone, the one that reads, “It is a privilege, not a right, to play, coach and work for the Dallas Cowboys.”

Prescott had heard from greats like Irvin about the improved outlook that can be gleaned after football is taken away. “You’ll realize there’s nothing in the world like this,” Irvin told him. When he patted that stone, Prescott understood.

The quarterback continued toward the field, anticipation building, reminding himself that “staying positive through all the bulls---, through the fight, was worth it.”

“Football has always been my getaway, my peace,” he says. “There’s no way to put into words the fact that, yeah, the last time I was out here, I got my leg snapped, and there was a lot of uncertainty in the world.” Now, he says, “when you’re doing so much, just being intentional and purposeful, it’s amazing to get to do the things you love to do again.”

Prescott follows that with a promise: “I’m telling you, I’m going to be a better player in every aspect when I’m back. A lot of the things that have happened, they've allowed me to be here, but I don't even know if I've reaped the strength yet. What I mean is … that's to come.”

Still, this isn’t a fairy tale. Not yet, anyway. As soon as Prescott finished practice, he received a call about his father, whose blood pressure had elevated, requiring paramedics to stop by and check on him. Then, Buffett was in a car accident. (Both would ultimately be fine.) But rather than allow his anxiety to build, Prescott simply breathed, adding context with each exhale. He will write his story. He alone could choose how to respond.

Prescott would summon those same vibes this summer, when he missed significant time during training camp with a right shoulder injury. Even though he hated missing all the reps he sought in practice, he did not attempt a single throw for weeks, jumping in for handoffs and simulating drop-backs—running through the motions, except for his favorite one. He reminded himself of Jeter’s advice. He knew he didn’t want to miss games like last year. He also watched motivational videos sent over by an assistant coach every morning at 5 a.m. One line in particular resonated: the patient man is the wealthiest one. The patient man returned to throwing in late August; his outlook, improved, his immediate future, not entirely clear.

He’s now a mental health advocate. In a sense, he’s reluctant—he feels guilty because of why he has become that, because his brother died and no amount of awareness raised or lives saved will bring him back. That’s what Prescott means when he says he has “credibility in this” now. But at the same time, there’s not an ounce of reluctance—“a life taken to save millions,” one more accomplishment to manifest.

Dak and Tad vowed to be vulnerable with each other. In the spring of 2021, Tad’s wife gave birth to a baby boy. They named him Jace McKenzie Prescott II. But Tad calls the newborn Mak, marking a way of honoring Dak, too.

On the anniversary of Jace’s death, the brothers ordered Jace’s favorite, Cicis Pizza. They ate at the kitchen table on those seven acres, near the note that Dak had kept, and decided to remember what they knew, rather than thinking about what they didn’t.

Through his soul searching, Prescott discovered that what he wants most will no longer define him. Not in sum. The twist: Because Prescott refuses to be reduced to one-or-the-other arguments—Super Bowl champion or failure—he’s more likely to win.

The talking heads define Prescott in binary terms: good enough or not, franchise quarterback or not. He ignores that exercise, looking away, never to look back. Inside the lounge, he lights an Davidoff Aniversario Short Perfecto. He takes a puff and asks the waitress to mute the televisions.

“Perspective,” he says, “has become my greatest strength.”

• The Falcons, Depression and Me

• The NFL’s Problems With the Deshaun Watson Investigation

• Copycatting the NFL’s Trendiest Offense Is Harder Than You Think

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.