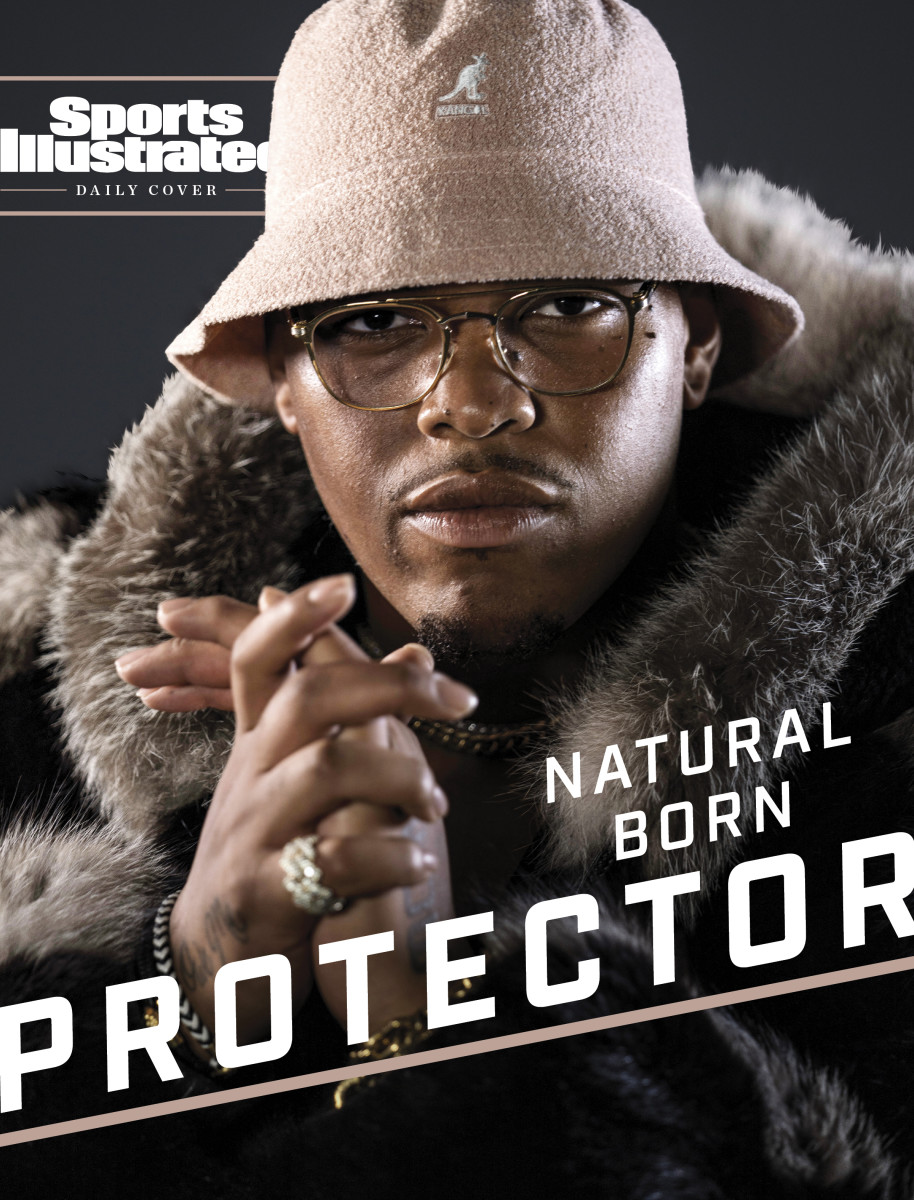

The Son of Zeus Forges a New Path

Like a weak-kneed kid wary of monsters, Orlando Brown Jr. tiptoed through the presidential suite at The Westin Kansas City at Crown Center, peeking around its plush couches, opening the closets in both bedrooms, checking behind the doors of all three bathrooms. It would’ve been a strange sight for any witness, were the 6-foot-8, 345-pounder not traveling alone, but Brown had reason to be cautious: As he figured, the space was so hilariously huge that some of his new Chiefs teammates had to be lurking in the shadows, itching to welcome Patrick Mahomes’s latest blind-side bouncer to town with a little scare.

By then, less than a week after the two-time defending AFC champions acquired him from the Ravens, Brown had grown accustomed to surprises. There was the late-April trade itself, which he’d learned about from an Adam Schefter tweet moments before his agent called. And the charter jet that the Chiefs dispatched days later to his home in Norman, Okla., the first time he had ever flown private (other than to road games). And the team camera crew that had greeted Brown on a darkened tarmac in Kansas City, documenting his arrival. “It was 9 or 10 o’clock,” Brown says. “I wasn’t expecting that.”

Another awaited him in his palatial hotel suite—Brown estimated it was twice the square footage of the apartment he occupied as a rookie in Baltimore—which proved free of would-be pranksters but stocked with wings, ribs, brisket and burnt ends from a local barbecue joint, again courtesy of the Chiefs. Mouthwatering as this spread was, Brown managed only a few bites before falling asleep. “Emotionally, all the love was just so overwhelming,” Brown says. “I was like, God, this is the craziest s--- I’ve ever experienced in my life.”

Just as wild, to some degree, was the fact that Brown was there at all, headlining an offseason overhaul of Kansas City’s offensive line after the pummeling Mahomes took in Super Bowl LV. For some it is one of football’s unlikeliest success stories. A third-round selection out of Oklahoma whose stock famously cratered thanks to—in his words—“the worst combine ever,” Brown goes even further when detailing his limitations in a modern game that prioritizes mobility from its blockers. “I’m the worst athlete in the NFL,” he says, “and I confidently stand proud on that.”

And yet it also makes perfect sense that Brown has risen to start for the league’s most dynamic passing attack—even if his debut, against Myles Garrett in Sunday’s 33–28 win over the Browns, was a little rocky. After all, the role not only represents a career culmination for the two-time Pro Bowler but also a fulfillment of a generational dream bequeathed from father to son.

As Brown had mused to himself while aboard the private jet, cruising to the land of barbecue and big expectations, “Man, everything is coming to fruition.”

Looking back, the fuzzy family photos hint at a predestined path. In one, baby Orlando Jr., a year and a half old and barely able to walk, dons a Ravens jersey. In another, he cradles one of his father’s size-17 football cleats as if it were a teddy bear. “When I snapped those,” his mother Mira Brown says now, “I realized there was a chance someday he’d want to be in the NFL.”

As Brown Jr. recalls, that goal didn’t crystalize for him until one overcast Sunday afternoon in October 2004. Then 8, he was in the family section in Baltimore to watch Orlando Brown Sr. and the Ravens host the Bills. “I don’t know what was so special about that game, but it was the first time I ever really paid attention to every rep for the O-line when my dad [and left tackle Jonathan Ogden] were on the field,” Brown Jr. says. “I remember thinking to myself, This is what I want to do when I grow up. And I can do it better.”

Known as Zeus for his herculean presence, the 6-foot-7, 360-pound Orlando Sr. cast a big shadow over his namesake. A native of inner-city D.C. and a defensive line convert who went undrafted out of South Carolina State in 1993, he persevered to play nine seasons at right tackle with the Browns and Ravens—despite a wayward penalty flag that temporarily blinded him—winning over cold hearts with his aggressive attitude and affable personality. “Zeus,” his first NFL head coach, Bill Belichick, said once, cracking a rare smile, “is probably one of my all-time favorite players.”

Aside from a single peewee season in kindergarten, though, Orlando Jr. was forbidden by his dad from playing organized football throughout his early childhood. “I think it was out of fear of me [and younger brothers Braxton and Justin] not living up to expectations,” Orlando Jr. says. “He had such a hard road, and I think he saw a lot of himself in me. It was like, Man, I don't want my son to go through what I went through as an athlete.”

Even so, Orlando Jr. soaked up all he could. He spent countless hours at Barnes & Noble, studying decades-old books of offensive-line drills. He tagged along to the Ravens’ facility whenever possible, working as a ball boy, battling his brothers in Madden in the players’ lounge, and scarfing down chicken salad whipped up by Manny, the team chef. Back home, his television viewing was typically limited to two choices: Sanford and Son reruns, and VHS tapes of his father’s NFL games. Often they would watch the latter together, Junior peppering Senior with questions about blocking techniques and schemes.

“Because I couldn’t play, I read and researched so much,” Orlando Jr. says. “I still was educating myself on the game, and he still was educating me as if I was playing. Which is, like, super weird.”

Finally, the summer before eighth grade, Orlando Jr. begged, through tears, to strap on the pads. “I’m like, I want to play, I’m the biggest kid in school, everybody makes fun of me,” Orlando Jr. recalls. “And he told me straight up, ‘I’ll let you play. But you can’t quit until you’ve got 10 years in the NFL and a Hall of Fame résumé. You’ve gotta approach this with the mindset that you’re gonna be the best left tackle ever.’ And 13-year-old me is like, ‘Yeah, O.K. I’ll do it.’ ”

To Orlando Sr., whose entire NFL career took place on the right side, left tackles like Ogden were the stars, the leaders of the line who earned the biggest salaries, commanded the most respect and inspired a best-selling book that would become a Hollywood blockbuster starring Sandra Bullock. Nothing less would suffice for his son. In one oft-told story, when a junior varsity coach at DeMatha (Md.) Catholic made the mistake of trying to deploy Orlando Jr. at right tackle, Zeus thundered back, “If he's not playing left tackle, put him on defense.” The coach relented.

Most other times Orlando Sr. was a hands-off mentor, hardly the type of sports parent eager to drag his son to the park and drill pass sets until dark. “I would have to really press him to do that,” Orlando Jr. says. But his guidance still outfitted Orlando Jr. with a foundation, both literally—when Orlando Jr. was starting out, “because I was so big,” he says, his dad brought him to the Ravens’ facility to get adult-sized cleats, gloves and other gear from the team equipment manager—and philosophically, as Senior scripted his vision for how Junior could break the mold of the smaller, cerebral left tackle. “You’re going to be bigger, you’re going to be more ferocious, you’re going to be more intense,” Orlando Sr. would say. “Take that right tackle mentality and apply it to the left. Finesse and power.”

By 2011, Orlando Jr. was living full time in Baltimore with his father, who had separated from Mira, and commuting an hour each way to DeMatha during the week, a decision that he had made with his future in mind. “My dad had already experienced what I was trying to get to,” he says. One day in late September, the Brown men had a long phone chat, mostly about a fight Orlando Jr. had sparked at a recent practice. “He was telling me to keep that old-school mindset, that it would take me far and long,” Orlando Jr. recalls.

It was the last bit of advice he ever got, and the last time they ever spoke.

Two days later, on Sept. 23, Orlando Sr. was found unresponsive in his home, dead at 40 due to complications from undiagnosed diabetes. Then in 10th grade, Orlando Jr. received the news at school when a fan tagged him in a rest-in-peace tweet. Stricken with grief, he nonetheless summoned the courage to ride with his mother to Orlando Sr.’s place, grabbing a few mementos strewn about the bedroom: an NFL duffel bag, a white bandana and a pair of Nike D-Tack lineman gloves all in his possession today.

The funeral was held at a Baptist church outside D.C., not far from where Zeus was raised. Hundreds of relatives, friends and former teammates attended. A slideshow looped pictures from football games and family outings; Belichick, tied up with in-season duties for the Patriots, sent a glowing letter that was read aloud. At one point, Orlando Jr. rose to deliver a eulogy. “He got up on that podium, and he was in tears,” Mira recalls. “I’ll never forget what he said: ‘I’m gonna make you proud.’ ”

Mark Fleetwood was sitting in his office at Peachtree Ridge (Ga.) High School in late 2011 when a pair of head-turning visitors ducked through the doorway in succession. The first was a familiar face: area native Tony Jones, a former NFL tackle who won two Super Bowls with the Broncos in the late 1990s. The second, while unknown to Fleetwood, was one of the biggest young men he had ever seen, standing three inches taller than the 6-foot-5 Jones and weighing nearly 450 pounds.

“Please tell me you’ve got some eligibility,” Fleetwood blurted, unable to restrain himself.

“Coach,” Orlando Jr. replied, “I’m 15.”

Sitting down, Brown explained that he had relocated to the greater Atlanta area with his mother and two brothers following his father’s sudden death, and that his godfather—Jones, who had blocked alongside Orlando Sr. in Cleveland—was helping him scope out high schools. He added that he was hoping to play varsity football, specifically left tackle, even though he had never made it higher than DeMatha’s JV. “You could tell he was green,” Fleetwood says, “but it was a very mature conversation.”

After Brown enrolled at Peachtree and entered offseason workouts, Fleetwood realized that the lineman who went by “Little Zeus” was perfectly serious about his goals. “He told me, ‘I’ve got a dream, man. I’ve got to prove myself. I want to do what my dad did—and more,’ ” Fleetwood recalls.

But it was also clear that Brown was far from perfect on the field, leading Fleetwood to bench him two games into his junior year. “Orlando, you can’t move; I can’t let you continue to start,” Fleetwood told him. Brown could’ve very well punted on the family dream there. The move to Georgia was meant to be a fresh start, free of a legacy that had loomed over him in Baltimore. “Everywhere we’d go, it’d be in my kids’ faces: Your dad passed; you’ve got shoes to fill,” Mira says.

Instead, he tackled the challenge, rising at 6 a.m. each morning to run before class and returning to the school track for more sprints after football practice. He also revamped his eating habits, switching to the Subway diet. All told, he shed close to 100 pounds by his senior season. “His mentor was gone, so he had to mature fast,” Mira says. “He had little brothers to look after. He took on the responsibility of, This is my job now. I’ve got to make sure you guys are good by sticking it out and being serious with football.”

As a senior, Mira recalls, Brown flattened so many opposing pass rushers that he was not only inducted into the local Touchdown Club but awarded a new nickname by its members: the Pancake Man. A three-star prospect, Brown was committed to Tennessee until the Volunteers, having overcommitted in their recruiting class, revoked his scholarship offer just before signing day, citing his low grades. He quickly found a home at Oklahoma—and, before long, another father figure, too.

Jammal Brown (no relation) first met Orlando Jr. at a football camp in the late 2000s. The latter was a middle-schooler tagging along with his dad, not yet permitted to play but more than big enough to hold blocking pads; the former, a unanimous all-America tackle for the Sooners who later won a Super Bowl and made two Pro Bowls, was less than impressed. “Big ol’ out-of-shape kid,” Jammal recalls.

Years later, after Zeus’s death, Jammal, who had been in high school when he lost his mother to lupus, reconnected with Orlando Jr. to extend a helping hand. Based in Norman, the now 40-year-old became an even more valuable resource once Orlando Jr. arrived, offering counsel on buying big-and-tall clothes to paying bills. More than that, though, Orlando Jr. found in Jammal someone who could help him get where he wanted to go as a player. So he drove to Jammal’s house in between two-a-days, breaking down the morning session on his iPad before returning to campus for the afternoon practice. They worked out together, studied the techniques of NFL left tackles together and shopped for healthy groceries together. “I give him a lot of credit for understanding and listening,” Jammal says.

The result: Brown won the starting job as a redshirt freshman, beating out a redshirt senior, and two years later became Oklahoma’s first unanimous All-America offensive lineman since his mentor. All the while, his motivation never wavered. It was there in his jersey number—78, what his dad rocked for two seasons with the Ravens—and underneath his helmet, where he wore that white bandana for every single snap.

It was also there in the two messages that he would write on athletic tape before games. The first: “RIP Dad.” The second: one of several Bruce Lee quotes, including “Be like water,” or “As you think so shall you become.” As Brown explains, “My dad was really into Bruce Lee and karate movies and s--- like that.”

Despite his success, Brown was realistic about his chances at the combine. “Every team I met with, I told them I was gonna be the slowest guy,” Brown says. “Most of your offenses, your tackles are elite athletes. I’m on the complete opposite side of the spectrum.” Even by those standards, though, his 5.85 40-yard dash, 14 bench press reps and 19.5-inch vertical jump were historically poor: No offensive lineman in the 2018 class did worse in those categories. And while it’s impossible to know just how much this affected Brown come draft day, it’s hard to imagine a consensus All-America with NFL bloodlines—not to mention the two-time Big 12 lineman of the year—otherwise plummeting past the first two and a half rounds, passed over in favor of 15 other offensive linemen.

Then, at the 83rd pick, Brown’s phone rang. On the other end was a voice he knew well. A decade or so earlier, on the day that Orlando Jr. had accompanied his dad to the Ravens’ facility for his first set of football gear, the Zeuses popped by the office of then GM Ozzie Newsome, who couldn’t resist prodding Orlando Jr. about his genetic potential. “He’s like, ‘You never know, 10 years from now, we could be drafting you; you could be a Raven!’ ” Brown says.

And so, when he saw that it was Newsome who was calling, Brown picked up in shock. “You’re playing, dawg,” he said. “You’re playing.”

“Has it been a long day for you, man?” Newsome replied.

“Long as hell, yessir,” Brown said.

Then Newsome asked, “Your dad smiling down right now?”

Life had come full circle. After the draft, landing at the Baltimore airport, Brown ran into Ed Reed, one of his dad’s old friends and teammates. “I remember him coming to the house when I was a boy,” Brown says. Manny the chef was still serving chicken salad in the cafeteria. A No. 78 jersey once again hung in a stall with his surname. A visit to his former elementary school, Pot Springs, was punctuated when a teacher produced a copy of a homework assignment in which Orlando had predicted that, when he grew up, he would play for the Ravens. “Still gives me goosebumps,” Brown says.

Just one catch: Like every other team he visited before the draft, Baltimore primarily envisioned Brown as a right tackle, a position he had never played thanks to his dad’s hard line. “You go from having a set foundation to having to create a whole new style of play at the next level,” he says. “The balance, the timing of my punch, my feet, my strength—it was so hard for me.”

For help he turned to a trusted source, bugging the Ravens’ video staff for copies of old games as far back as 1996. “To be honest, I didn’t have much to go off but my father’s tape,” Brown says. The lessons helped Brown thrive in Baltimore’s ground-based offense, carving running lanes for Lamar Jackson and making the Pro Bowl in his second season. And yet, even though the game has evolved to the point that right tackles are just as crucial (and handsomely paid) as their counterparts—the emphasis on quicker passing offenses as well as a trend of star pass rushers lining up primarily across from the right side of the offensive formation has erased any practical difference—Brown never lost sight of where he really wanted to be.

His big chance finally came early last October, heading into Week 4 against Washington, when Brown asked coach John Harbaugh if he could step in for longtime left tackle Ronnie Stanley, who was out with a shoulder injury. Harbaugh agreed, Brown says, but on short notice: Brown only slid over before the Saturday walkthrough, giving him little time to prepare for a position he hadn’t played in three years. “I basically got thrown in the fire,” he says. But the Ravens won 31–17, Brown was named the team’s offensive player of the game and gifted a commemorative ball and afterward he called his mentor in tears. “He was like, ‘Bro, they gave me the opportunity; I’m just so thankful,’ ” Jammal Brown says.

The rush seemed short-lived when Stanley returned the following week, and Brown went back to right tackle. But then, against the Steelers in Week 8, Stanley went down with a season-ending broken ankle. The sight of Stanley leaving Heinz Field in an air cast devastated Brown, but it was also a second chance to seize his dream. Starting on Jackson’s blind side for the rest of the year, Brown allowed zero sacks or hits in nearly 400 passing snaps and made a second straight Pro Bowl.

All of which led Brown to do some soul-searching after the Ravens lost to Buffalo in the divisional round. Speaking to his mother, his mentor, and his agents, Joe Panos and Justin Schulman, he made a tough call: With Stanley having signed a five-year, $98.75 million extension two days before his ankle injury—“which was the right thing, he’s an amazing player,” Brown says—and the path to his job therefore blocked, Brown would have to leave Baltimore to get where he really wanted to go.

As he tweeted on January 29, simply, “I’m a LEFT Tackle.”

Among those caught off-guard by this were the Ravens, who expressed their displeasure at Brown making his stance public before telling team brass. That his agents were nonetheless granted permission to speak with other teams can be read, at least in part, as validation of Brown’s goal. “Given [Baltimore GM] Eric [DeCosta]’s relationship with the family, he understood it,” Schulman says.

Studying the offseason tackle landscape in early February, Brown says, he figured that his best chances lay with the Jaguars, the Chargers, the Washington Football Team and “possibly” his dad’s old coach in New England. But when his camp began gauging interest in him, pushback returned in several areas. One was the potentially steep cost of a trade. (“[DeCosta] wasn’t going to just give him away,” Schulman says.) Another was the perception that Brown’s new team would have to include a contract extension as part of the trade, given that his rookie deal was set to expire at the end of the 2021 season. (“A big hurdle,” Schulman says.) Finally, many clubs expressed concern about Brown’s ability to succeed at left tackle in a pro-style passing offense. (“Which I understand,” Brown says. “I blocked for Lamar; I still run a 5.8, you know what I mean?”)

When more than two months passed without a bite, Brown took a risk and bet on himself, letting teams know that he would play out his contract without an extension. That was enough to interest the Chiefs, who had signed prized left guard Joe Thuney but whiffed in the Trent Williams sweepstakes to replace outgoing tackle Eric Fisher, leaving a gaping hole in a unit that, riddled by injury, allowed Patrick Mahomes to be pressured more times (29) than any quarterback in Super Bowl history.

After another two weeks of back-and-forth, the six-pick, one-player deal was finalized while Brown was taking pass sets at Oklahoma’s indoor facility in Norman as part of his offseason training. “He was shocked,” Schulman says. A flurry of phone calls with various Chiefs officials followed—GM Brett Veach, coach Andy Reid, chairman Clark Hunt—as well as with DeCosta and Ravens majority owner Steve Bisciotti, to whom Brown expressed his emotional thanks.

“What they did for my family from the beginning, giving my dad an opportunity, and then turning around years later and giving me an opportunity,” Brown says, “it was so hard to walk away from that.”

Then he put down his phone and finished his pass sets.

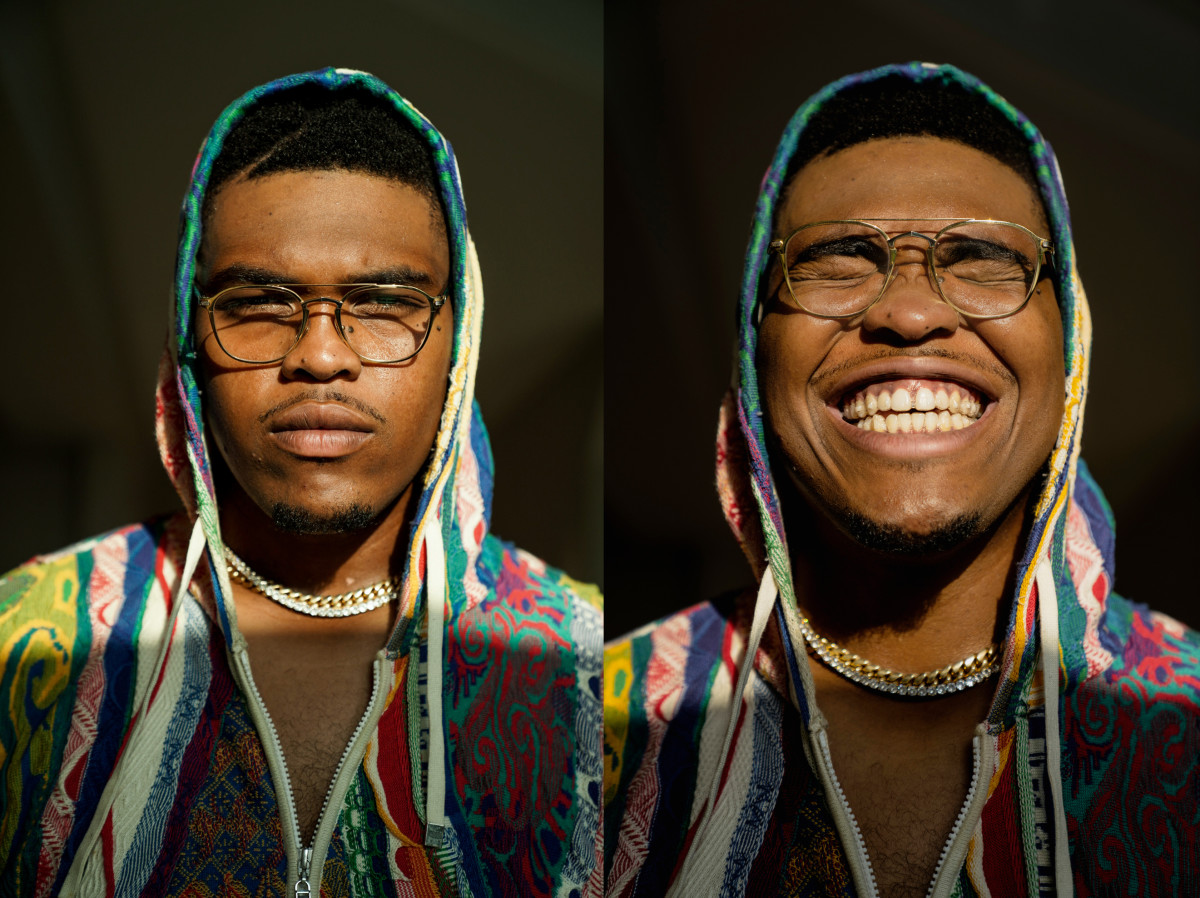

Little Zeus appears on the Zoom screen from his house in Kansas City, sitting in front of a white wall and wearing a black T-shirt that reads “FCUK EXCUSES.” It’s mid-August, halfway through Chiefs training camp. “I’m having a blast, man,” he says. “It’s been so much fun, just learning the system; it reminds me of being a kid again—the love for the left tackle position. I’m super excited.”

Clearly Chiefs fans are stoked, too: A few recognized him at the Westin and asked for pictures when he visited after the trade in April; several months later, as he was just getting settled in their Overland Park neighborhood with his girlfriend and infant son, an otherwise ordinary trip to Target for assorted home goods resulted in so many autograph requests that he placed a gobsmacked call to Mira, who recalls him quipping, “Mommy, I just got swarmed at Target; I need security. I’m a celebrity out here!”

Among those heralding Brown’s arrival was his former college teammate and roommate. A lifelong diehard from Topeka, Kansas, Quinn Mittermeier had been living in Norman when news broke of Brown’s trade—at which point he went to his storage facility and surprised Brown mid-pass set at the Sooners’ facility, clad in a Chiefs hat and a Royals shirt, playing the team’s Arrowhead Chop chant on his phone.

Not long before training camp, Mittermeier, 25, now a legal assistant in Southern California, accompanied Brown to a Royals game, where Mahomes had booked a suite. Other Chiefs offensive linemen were invited, too, including 2021 draft picks Trey Smith and Creed Humphrey, who opened the season at right guard and center, respectively. Watching their interactions, Mittermeier was struck with how the incoming rookies gravitated toward Brown. “He’s a leader now,” Mittermeier says.

To fit into Reid and Eric Bieniemy’s system, which attempted 13.8 more passes per game than the Ravens’ offense last season, Brown must grow in other ways, too. Specifically he cites Kansas City’s fondness for jet sweeps, play-action and other disguised plays as a chance to showcase how he can “manipulate blocks,” coming off the snap the same way each time no matter run or pass. “So often the guys that play this position are super athletes—Lane Johnson, Ronnie Stanley, Laremy Tunsil,” Brown says. “Even though it’s a play-action, they may still be able to just take a pass set every play, mirror the guy,and leave it at that. That’s not my game. I’m gonna manipulate my blocks and make them all feel the same to this guy I’m going against. That's where I’m able to take advantage of people.”

True to form, he has been studying up. Curious how Reid had used bigger tackles in the past, Brown sought out tape of former Eagles Tra Thomas, King Dunlap and Jason Peters; when Mittermeier visited in Kansas City, Brown couldn’t wait to hop on YouTube and share some of Thuney’s snaps. He even dug up a DVD player and watched some early 2000s games from the tail end of his dad’s career, noticing striking similarities in their fundamentals and fluidity. “I was taken away [by] how much his game grew as a player,” Brown says. “Although he dealt with more injuries and stuff like that, man, he was just such a better player than he was early on. Even with one eye, he's out there kicking a--.”

They are becoming alike in many other ways, starting with their (lack of) vision: Though Brown uses glasses off the field he refuses to wear contact lenses during games, considering them an unwelcome “distraction,” he says. “If I had to get hand signals from the sideline, we’d be f-----.”

Family and friends, meanwhile, look at Brown and see Zeus’s silliness, visible everywhere from his reputedly spot-on impressions, usually of his coaches, to the way Brown introduced Tyreek Hill to the origins of his “Pancake Man” nickname during OTAs, belly-bumping the star receiver to the grass as they jumped to celebrate a touchdown. Then there are the contents of Brown’s closet, overflowing with his dad’s mink fur coats and other retro fashion choices. Senior was an avid collector of exotic cars who often dropped off Orlando Jr. at elementary school in a Rolls-Royce Phantom, yet preached financial piety: “He told me, ‘Just because I own 11 cars doesn’t mean that you should. Don't chase my lifestyle. Create your own and make it better.’” Indeed, Little Zeus’s purchasing habits have been far less expensive. He has a collection of “at least 12” supposedly lucky foxtails, each one bought on eBay from the same Montana woman. "I might be the only person that's keeping her in business," he says.

Perhaps most of all, though, Brown is becoming his father because he too has become a father. His son’s full name is Orlando Brown III, but Brown calls him Three, or Butter, because he “looks like a butterball.” And while Brown emphasizes his desire for his son to “just enjoy being a kid” and not feel pressure to follow in two generations of size-umpteen cleats, he already knows what he will do if Orlando III ever asks to join the family business and play football. “I’m gonna give him everything I got,” Brown says. “All of it. The film, all my tips and tricks, whatever he needs to know.”

Just like his dad did for him. Maybe even better.

• Inside Tom Brady's Forgotten Rookie Year

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

• How the Bucs Are Leading a Linebacker Revival

• The 9/11 Story That Inspired Tom Brady