The Discovery, Mystery and Controversy of the Original Horns

Mr. H is tall, bald, white and 45 years old. He is personable, soft-spoken and curious. He lives comfortably, with his girlfriend, mostly in central California. His wealth derives from collecting: watches and diamonds, jewelry and art, gold and silver and coins. He travels the state visiting jewelry stores, secondhand stores and antique stores, looking for rare finds or buying whole estates. The vast majority of his purchases hold no historical significance. They are, as he puts it, “someone else’s treasures.”

On a typical day in an atypical life, Mr. H and his partners will spend between $10,000 and $50,000. He describes his group as “volume buyers” who rely on sources and their tips. Sometimes, he will shell out much more, deep into the millions, landing hundreds of gold coins, rare Impressionist paintings, or sport model vintage Rolexes from the 1960s—“anything, really, that’s of exceptional quality or value,” he says. And, though rarely, sometimes his business intersects with sports.

In another lifetime, Mr. H ran a baseball card shop. He still follows the market, tracking the latest boom, and has netted a Babe Ruth rookie card and the coveted 1952 Topps Mickey Mantle. Then there's his more recent discovery, from a purchase in Palm Springs, Calif., Mr. H and his partners bought several items that once belonged to Fred Gehrke, the late NFL running back and executive who holds a special place in the Pro Football Hall of Fame, where he occupies a wing that’s home to few members. In that sale, Mr. H discovered an artifact that might be of vast historical significance ... or not.

Mr. H does not want to be identified in this story, nor do his friends; all maintain they’re not relevant to the narrative. That’s debatable—because of what they found in Palm Springs, which they paid roughly $40,000 for last year. “I didn’t realize how important what I bought [could be],” Mr. H says.

Hence the relevance, I told him, as we embarked on a reporting journey that was long, perplexing and just plain weird. He laughed, not budging. His insistence on anonymity marked the first unexpected twist in a story that unspooled more like a detective caper, a tale about a football helmet, a stroke of marketing genius and the man who, 75 years ago, was responsible for both.

THE IMPLICATIONS

The dealer who tipped the buyers to the items hosted them at an office in Palm Springs. Mr. H figured he would be shown the usual assortment of someone else’s treasures. When this dealer walked into that office, he paraded in an array of sports-centric items: cleats with wooden blocks screwed onto the bottom to serve as spikes; framed, handwritten letters from football luminaries like commissioner Pete Rozelle; a championship ring. They seemed to speak to a person who valued history and his place in it. The buyers started to wonder: Who was this Gehrke, anyway?

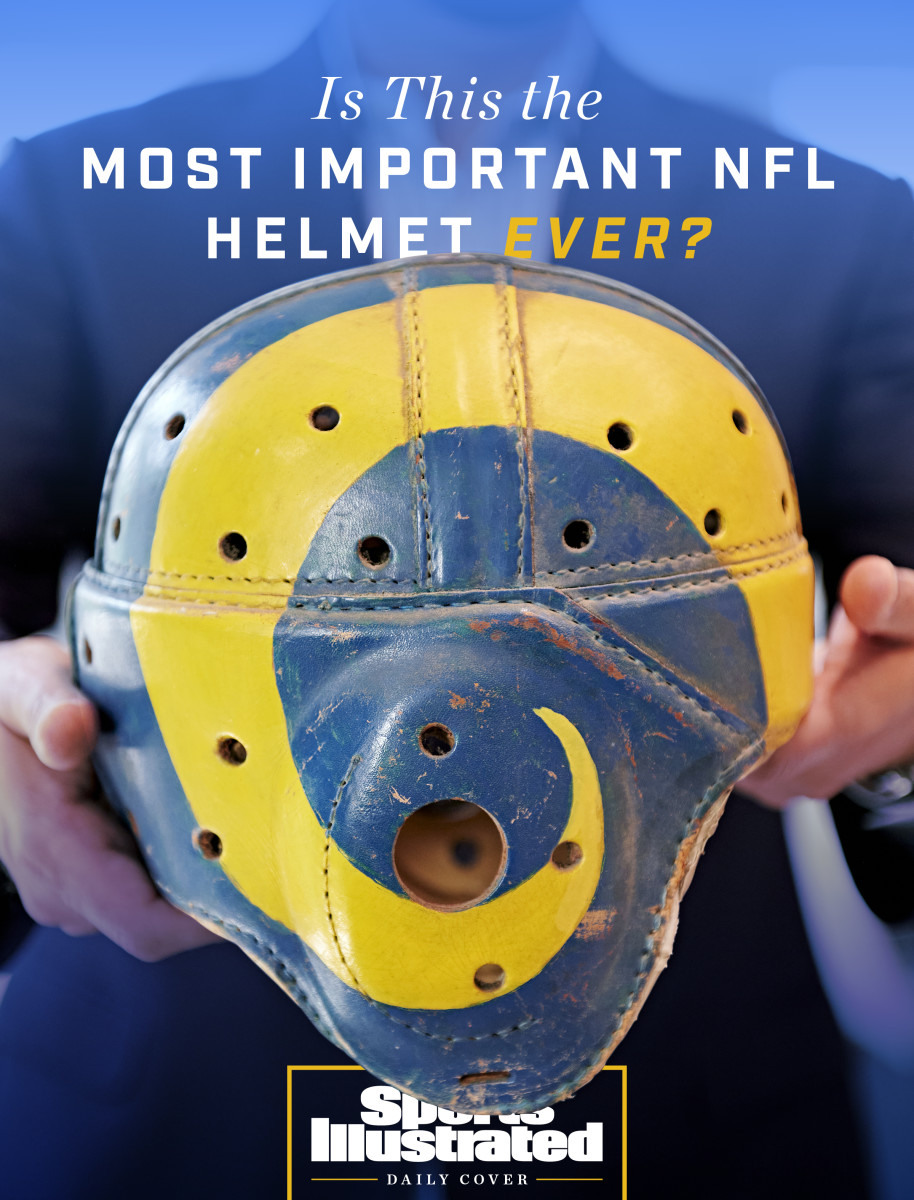

The answer started with what the dealer held in his hands—an unpolished, unfinished and unusual item that, at first glance, looked more like someone else’s junk. It was an old Rams football helmet covered in markings, lines scribbled everywhere like hieroglyphic writings on the wall of an ancient cave. This particular helmet, he told the buyers, had been designed, created and painted by Gehrke.

Mr. H stepped outside and tapped relevant terms into a search engine on his phone. The sell, wild as it sounded, seemed like it could be true. The dealer pointed out the horns that had been drawn on the helmet; look closely and they could see multiple revisions, lines of varying length visible beneath several coats of chipped paint.

Seeking informed opinions from the sports world, Mr. H first called one partner who happened to love the Rams. Buy it, the partner said. Mr. H then called Rick Mirigian, a boxing manager/promoter for top junior welterweight Jose Ramirez, among others. A collector calling a boxing manager to affirm the value of an estate sale? Another ridiculous twist. But Mirigian conducted his own search and concurred with the Rams-fan consultant.

Thus began an obsession for all involved. So, too, began my foray into the realm of amateur authentication. Mirigian spent hours studying pictures of the helmet, trying to ascertain whether they had stumbled upon what he believed might be the prototype for the first logoed helmet in NFL history. “Like a rare Picasso or Rembrandt had been unearthed or something,” he says.

His promotional instincts kicked in. He wondered: If true, what was it worth? To the Rams? A museum? The NFL?

Mirigian started considering logos and how they had changed sports, leading to merchandise—so, so, so much merchandise, millions of hats and T-shirts and coffee cups sold, billions of dollars banked. Logos would come to define iconic franchises. They would connect communities. They would become an integral part of the sports landscape. Think: Cowboys star, Lakers basketball, Yankees interlocking “NY.” Also: Rams horns.

Mirigian couldn’t sleep, possibilities unspooling in his head like complex math equations. To him, everything lined up. He told Mr. H, “This may be way more important than you think.” Mirigian reminded his friend that the next Super Bowl, LVI, will be held at SoFi Stadium in Los Angeles. He dreamed of displaying their discovery.

THE PROMOTER

I knew Mirigian from the nothing-like-it world of boxing, where even the characters who abound found him hilarious and a tad extreme. Whenever we connect, my wife laughs—“Oh, that guy called again.” That’s because, inevitably, when I ask Rick how he’s doing, he will launch into one rant or another on disastrous promotions, dizzying negotiations, bogus contracts, shady rivals, anxiety, or number of days gone by without sleep.

Wary but intrigued, I jumped into the deep end of the speculation pool. Gehrke was the artist who designed the prototype, advancing the evolution of football helmets more than any person or company since they were invented.

Additional research helped explain the potential holy-s--- nature of their find, starting with the NFL, a league that generated $12.2 billion in revenue last year. The logo directly impacted massive television contracts and corporate sponsorship, along with licensing deals for the league and its individual teams. The worth of the logos baked into those billions seemed several levels beyond significant. I began to buy Mirigian’s sell: The helmet locked away in Mr. H’s safe could have changed not just football but all sports.

THE SELLER?

It was one thing for this group to believe they had accidentally obtained a substantial piece of NFL history. It was another thing entirely to answer the question we all desperately wanted clarity on: Were they right?

The helmet wasn’t like a baseball card, where condition mattered and a grade would determine value. Since few prototypes existed—perhaps only one, even—all that counted was whether this was that.

They asked the dealer to reach out to Jean Gehrke, Fred’s second wife. They wanted confirmations, a signature, photos of Fred working on his prototype that could be used for comparison.

A week passed. Then two. Then three. With no reason to rush, none of the buyers panicked. They knew that Jean was in her 80s, that everyone was living through a pandemic.

They could wait, and while they did, they came to a consensus: They did not plan to auction the helmet to the highest bidder. Instead, they desired to tell the broader story of how merchandise came to define sports. They believed their helmet told that story through its perfect imperfections, all the markings, the starts and stops of a logo taking shape. This was the football equivalent of Albert Einstein’s notes on the theory of relativity, an idea—one that would change the world—at the moment of conception.

THE SKEPTIC

My initial reaction mixed awe with doubt. I bought Mirigian’s central thesis—what they believed was plausible, even with implausible elements. Part of me, though, wondered if the tale was fantastical, grounded in a misguided premise, the desire to want the story to be true. I conveyed that sentiment to Mirigian. He said that verifying the helmet would “not be a big headache.” He had contacts, after all—a favorite line of his. And, to be fair, those contacts had always proven helpful previously. We settled on a compromise: I would do some digging.

A colleague helped me find a number for Jean Gerhke, who still lives in Palm Springs. I left a message. Then another. I sent a few emails but initially had the wrong address. After about a week, she called back. Her demeanor was pleasant, her vibe chatty. We briefly discussed the buyers’ find, and she raised an important, potentially damaging point at the outset.

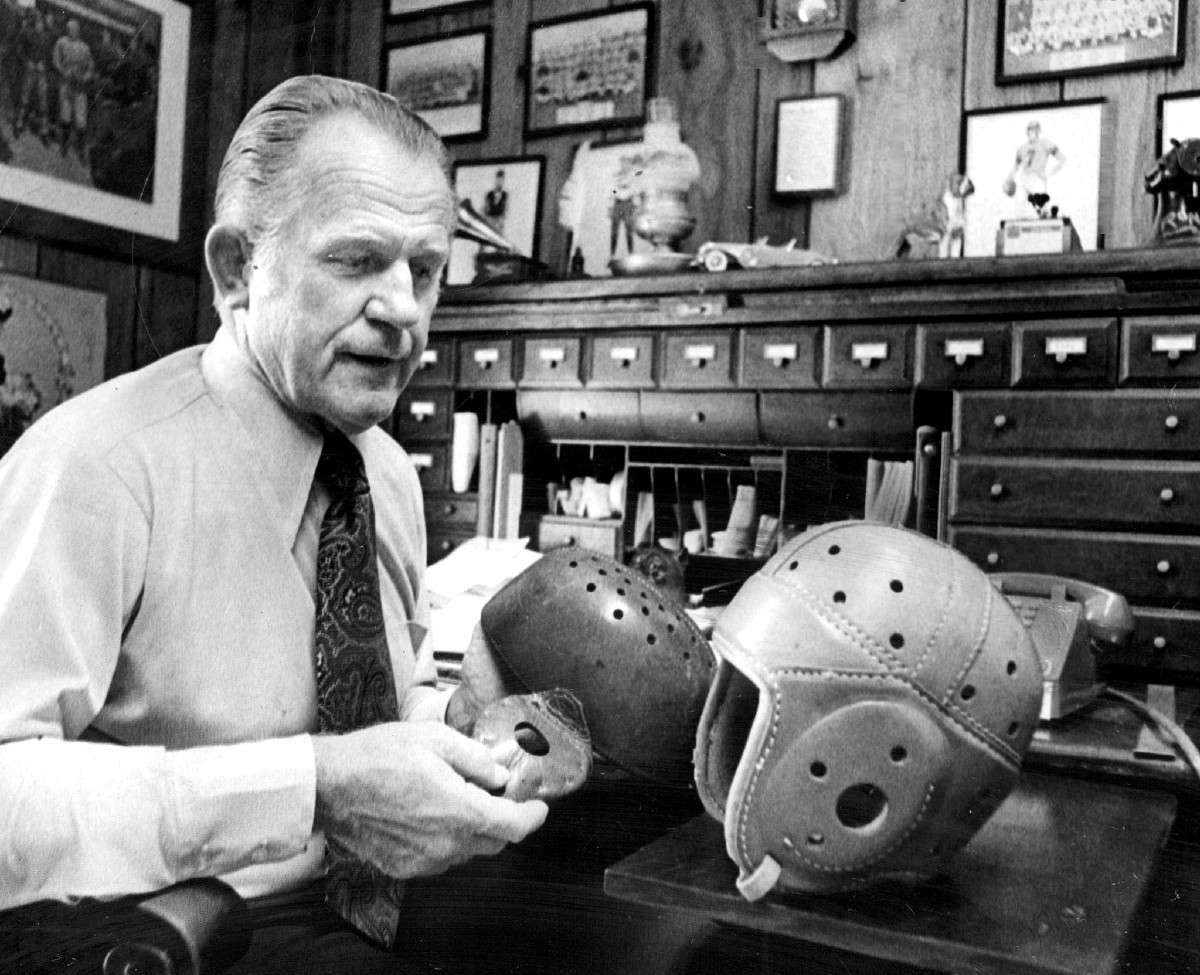

Fred had actually designed two helmets, she said; one before he met her, the actual prototype for what would become the versions with logos we see today; and another, smaller version, one he fashioned later, in the 1970s, for the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

I asked if she knew which helmet they had purchased. “I don’t,” she answered.

Jean filled in what she could. She did not know the buyers—Jean had sold everything to Paul Welch, proprietor of Coachella Valley Jewelry and Loan, a pawn shop in nearby Palm Desert, who then sold it to Mr. H and his partners. She was not in regular contact with Fred’s children from a previous marriage. “I just sold a lot of Fred’s stuff,” she said. “I really can’t say. But I’m the only one that had anything of Fred’s, except I did give his children a lot of the Rams stuff.”

Her answer was both helpful and confusing. The fact that she had sold his “stuff” aligned with the buyers’ story. The fact that she had that stuff spoke to her relationship with Fred, their bond. The most likely person to have possessed a prototype two decades after his death was Jean. And yet, this was a Rams helmet. Perhaps one of the children had the prototype. I wrote in my notes: seems like she knows more than she’s saying.

I wanted to know more. So I asked her, “Tell me about Fred.”

THE RUNNING BACK

Fred met Jean at Northrop Aviation, an American aircraft manufacturer, in the 1960s, years after retiring from football. He worked as a draftsman, a “technical illustrator,” and, eventually, he would oversee the photo lab, the print shop and the art department. She was early into her career, assisting at the drafting table. He was the kindest, gentlest person she had ever met. Despite 40 years of marriage, Jean says she never saw Fred angry. He didn’t brag. Nor did he traffic in nostalgia, or tell the same story over and over, even though a slice of NFL history—one that would make a lot of people rich—began with him. He would tell Jean that if he “died tomorrow,” he had “lived a full, fantastic, wonderful life; every day a pleasure, even work.”

“It made me mad,” she says, laughing. “He was just so damn happy all the time.”

The happy man was many things: father, husband, running back, broadcaster, general manager—and, through it all, at his core, an innovator, creator, artist. Fred liked to joke about how he played 10 seasons in pro football and his only chance to “end up in the Hall of Fame would be from my darn artwork.”

Over time and with much prodding, she pried details from Fred to piece together his remarkable life. He had grown up in Salt Lake City, where he would sneak into Utes football games and build model airplanes for fun. Even then, the duality that defined his life was prominent. He graduated with a degree in art from Utah in 1939, where he made all-conference, playing running back and cornerback, returning punts and kickoffs. He also set school records for the javelin toss and won three straight conference diving titles.

He played for the Cleveland/Los Angeles Rams, the San Francisco 49ers and the Chicago Cardinals from 1940 to ’50. Mostly. World War II paused his career after only one season. Gehrke wanted to fight in the war but failed his physical. But he still wished to contribute, so he started with Northrop in the engineering department. He kept in shape by playing for lower-level teams—the L.A. Bulldogs, L.A. Wildcats and the Hollywood Bears—which the NFL allowed. When the war ended, he returned to the Rams.

His first season back, in ’45, Gehrke beat out two Heisman Trophy winners (Tom Harmon and Les Horvath) for the starting tailback gig, then led the league in yards per rush (6.3) and punt-return average (15.0). Pro Football Illustrated named him first-team All-Pro. The Rams lost only once that season and captured the NFL title with a victory over Washington.

Gehrke retired a few seasons later, at 31, then moved into the broadcast booth. He later shifted into personnel, serving as the Broncos’ general manager from 1977 through ’81. Eventually, he went back to Northrop, where he met Jean and helped design the P-61 Black Widow, the first U.S. warplane that could operate at night. He remained in football, though, moonlighting as a broadcast analyst for college games every weekend.

He died in 2002, at age 83, but not before being elected to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. His induction was rare, like his life, in that Gehrke did not reach pro football immortality for how he played, analyzed, or drafted. He reached that immortality through his art.

THE ARTIST

From the day that Jean met Fred, she could see that he defined himself less by one part of his life—football—and more by the totality of his existence. In fact, creating was the calling closest to his soul. He loved woodworking and fashioned for her a coffee table, a chest side table and a breakfast nook.

By then, he had already created a version of the facemask—and during his career. This happened in 1946. Gehrke would later tell several reporters that he took a handoff and shot through the line, cruising down field until defenders not only caught him but broke his nose. Unable to slow the bleeding, Gehrke had to come out. In the next game, defenders re-broke that nose. Same thing in the next game, according to his interviews.

The next offseason, Gehrke decided he was done with broken beaks. He transformed a chunk of clay into the shape of half a human skull. He brought the molding to Northrop and asked the machinists who ran the power-stamping machines to mold aluminum to the clay. They did, and this football Frankenstein creation covered his forehead and his nose and rested on the cheekbones. But Gehrke wasn’t done. His grandfather worked as a shoemaker, and Gehrke asked if he could cover the contraption in leather and attach it to a helmet.

Gehrke played the next season with a facemask, more proof of his status as football’s great architect. His Twitter handle might have been @theRBinventor. He would later say that the initial version obstructed his vision. But, bonus: no more broken noses.

On his first day in personnel with the Broncos, Gehrke asked to tour the offices to study their design. He did not like what he saw. He sometimes told one story about meeting with Gerald Phipps, then owner of their dilapidated digs. When Gehrke rose to greet his boss, his head collided with the ceiling.

Denver had the right man for an office makeover. Gehrke fixed the leaky plumbing in the dressing room, added working shower heads (only two were functional) and found space for a full-size practice field (after realizing the version he inherited topped out at about 80 yards). That he performed all the repair work while working as director of player personnel marked another startling twist that spoke to life in the pre-logo NFL. More importantly, he asked for these tasks, because he knew he could improve on existing designs, just like he had years earlier, with the helmet.

Gehrke hired coach Red Miller, acquired quarterback Craig Morton and went to Super Bowl XII, where the Broncos lost to the Cowboys. Gehrke helped design the rings given out to commemorate their conference championship, reinforcing his duality once more.

As he ascended from exec to GM to vice president, Gehrke also tutored punters and kickers; forever efficient, the ultimate multitasker. At one point, he realized the kickers had no real way to practice on the sidelines. He called over the equipment manager and asked for netting, which he fashioned onto aluminum pipes. The first kicking net was born in that moment of inventive absurdity. Gehrke obtained a patent he held until the rights expired.

In every football stadium, at every level of the sport, kickers warm up by blasting attempts into nets that are stationed on the sideline. They also jog onto fields wearing facemasks on their helmets. And those creations, both of which changed football and long ago became ubiquitous, would comprise only a small portion of his legacy, two remarkable footnotes to his greatest impact—what the buyers believed they had discovered in Palm Springs.

THE DA VINCI OF FOOTBALL HELMETS

They believed they had a prototype. I wanted to believe them. Jean Gehrke wasn’t sure. Looking for consensus, of any sort, I started looking into the helmet itself. Wherever this prototype actually was, no one disputed how it came to be.

The path to their discovery—maybe—began in a garage in late 1947 or ’48 (accounts differ as to exactly when). Gehrke played for an owner, Dan Reeves, who was considered a visionary in his own right. Reeves is often cited as the first person to move an NFL team west of the Rocky Mountains (’46), the first to hire Black employees (also ’46) and the first to televise games (’51).

Gehrke told reporters that his owner cared more than his counterparts about his team’s appearance. That got the running back to thinking. Couldn’t the helmets, specifically how they looked, be easily improved? Certain that they could, Gehrke began sketching with pens and pencils long before he sat down in that garage. After one practice the previous season, he showed his favorite draft to his coach, Bob Snyder, who, like all editors, wanted something more. Snyder told Gehrke that he could not visualize the drawing on their headgear, so he added, “Paint it on a helmet.”

Gehrke did, inside that garage. His story of that afternoon remained remarkably consistent over the years. He took a brown, leather helmet and first painted it blue. He then rendered, freehand, an outline of ram horns, scribbled in gold paint. The gold color, Gehrke often lamented, would later be changed to white, because television executives liked that hue better. Gehrke considered the blue-and-gold original more aesthetically pleasing. Reeves agreed, signing off on the design and checking with the NFL about any legal issues. There were none.

Snyder told Gehrke to paint 75 helmets exactly that same way, and Gehrke often told reporters that he did, decorating them all by hand. He received $1 per helmet for his toiling and nothing for two seasons of touch-ups. But that debut, in the first game of the next season, was worth more than money. No team had ever run onto a pro football field that way, with a symbol painted on the equipment atop their heads. The crowd showered the Rams with a standing ovation that lasted for five minutes. It seemed to understand the history.

By ’49, the sporting goods company Riddell had incorporated Gehrke’s design in their helmets, by baking the horns into the plastic shell. The Colts would soon adapt a logoed version of their headgear—the famous horseshoe. Before long, every team in the NFL except the Browns and Steelers had slapped logos onto helmets, and every team affixed them to everything else, from coffee mugs to keychains to temporary tattoos, all available, for the right price. Gehrke likely had no idea then just how much one afternoon in his garage would change pro football. He certainly could never have envisioned where the helmet—maybe—would end up.

THE EVOLUTION

The more that Mr. H and his friends researched Gehrke and his art, the more they felt like they had come to know the man. Same for me. We sent old pictures back and forth, marveling at the history Gehrke kept inside his office, the volume of what he had saved. It seemed like he knew, at minimum, that his life could later help to tell a larger story, the larger story, of how the NFL became a billion-dollar behemoth.

We read—and reread—a Sports Illustrated magazine piece on Gehrke from 1994. Perfect headline: “Rembrandt of the Rams.” Gehrke told author Mark Mandernach that he stored brushes near cans of blue and gold paint inside his locker for those touch-ups. The piece, written almost 50 years after his playing career concluded, placed Gehrke in his proper historical context. He had made the Hall for his artistic and inventive contributions rather than anything he ever did on a football field, just as he predicted. Gehrke would become the first recipient of the Daniel F. Reeves Memorial Pioneer Award. The symmetry was ideal, the honor named after his owner from those head-bumping-ceiling days.

The story also mentioned an exhibit that commemorated Gehrke’s lasting impact on his sport. That caught my attention. Was the prototype already in Canton, Ohio? Had we spent a few months chasing the wrong ghost?

I reached out to the Hall. A week went by. Then another. Then I heard from Jason Aikens, their collections curator. I stared at the bearded face on his LinkedIn profile while I waited for his call. I hoped he could provide the elusive clarity we sought. But he didn’t seem that fascinated, and I wondered if he received similar requests all the time. This re-elevated my dwindling skepticism.

I took him through what Jean had said about two helmets of differing sizes painted decades apart. I told him about the picture she had taken in the 1970s that shows Fred painting the smaller version and signing the inside, just like the original prototype.

Aikens said that he would look into everything the Hall had related to Gehrke. But before we hung up, I asked for a brief history on helmets, in order to better understand the prototype’s historical significance. Aikens laughed, noting that he had grown up as a Rams fan. He loved the horns, loved the logo. And now, right at that moment, he began to explain.

Fans of helmets will not find a consensus on the first one. But many point to Admiral Joseph Reeves, who, as legend has it, had taken so many blows to the head that a doctor told him even one more wallop could give him “instant insanity.”

The evolution started around then.

1900s: soft, leather, “optional” skull caps were donned by players who chose to wear them.

1920s: hardened leather versions made their debut.

1930s: that same version received an upgrade, with harder, thicker leather.

1939: Riddel invented the first plastic, non-logoed iteration.

1940s: Helmet met chin strap.

1941: Production of plastic versions dropped, due to scarcity of material necessary for the U.S. war effort.

1943: The NFL began requiring all players to wear headgear during games. Soon after: plastic helmet manufacturing resumed, only to be halted, when those helmets quickly shattered into pieces and the NFL banned them once more. Soon after that: The padded plastic helmet was rolled out.

1946: Gehrke invented his version of the facemask.

He eventually found his original drawing and sent it to Snyder, his old coach. Snyder had it framed and hung the diagram in his home office. Someone reportedly offered him $10,000 for it, and that wasn’t even the prototype, just the initial sketch of it, the offer now half a century old. If the buyers had the real thing, Aikens believed they had a vital piece of football history.

I told him I planned to see the helmet myself in a few weeks. He told me to look for markings on the inside and what he called “wear patterns” from in-game use. The model that Gehrke painted in the 70s would not have either.

Before we hung up, I had to ask: Is it possible?

His response echoed my own thoughts.

“I don’t know.”

THE PHONE CALL, PART I

Months after our initial correspondence, while I was on a fishing trip in the Louisiana bayou back in April, my phone buzzed during a crawfish boil. It was Jean Gehrke. She left a message and called back. And called back. And called back. Sensing elevated alarm, I returned the call.

This time, her tone was different. She sounded distressed. She also said that she now believed that the prototype was already in the Hall of Fame, insisting the buyers had the 1970s version.

I was confused. Was she right? And, if she was wrong, was this story causing her undue stress? I wrote down: seems like sellers’ remorse but pursue.

I knew then what was necessary: I had to go see this artifact for myself.

THE VISIT

The temporary home to the helmet that had sparked a monthslong debate was a ninth-floor condominium in Westwood, Calif. Mr. H stays there when he’s in Los Angeles, the glittery landscape stretching for miles beyond his windows. “I haven’t even unwrapped this yet,” he says, as he carefully removes the bubble wrap that had been taped over a glass display. He then unscrews the helmet from its mount and places it on the glass kitchen table. Tiny pieces fall away, NFL history—maybe—in the form of leather crumbs from the 1940s.

Finally, there it was. The holy grail—or not. I followed Aikens’s instructions. I looked inside, and it took less than five seconds to find Gehrke’s signature. There also appeared to be “wear patterns” and something else, horns inside of horns, like sketches, as if Gehrke had tried out various sizes before settling on the version that he painted. The headgear also, as Mr. H pointed out, would have fit atop his head. There was nothing “mini” about it.

It sure looked like the prototype, to my untrained eye, as Mr. H continued to build his case. He showed off the rest of the estate: personal correspondence with football notables like Jim Thorpe and Otto Graham; artwork made for George Halas, fashioned from 290 pieces of glass; leather helmets believed to be more than a century old; a coin from the 1976 Hall of Fame game; the Broncos conference championship ring that Gehrke had helped design; old driver’s licenses that belonged to Gehrke. The face of that running back/artist momentarily transfixed me. What would Fred Gehrke make of all this?

At minimum, I agreed with Mr. H that Gerhke seemed “like a guy who cared about the evolution of the game.” Why else would he have kept everything he stored away? “I don’t think he knew how people would appreciate memorabilia today,” Mr. H continued. “But he saved stuff for a reason.”

I asked Mr. H what his ideal scenario would look like. “It belongs here,” he said, meaning Los Angeles, with the Rams. “It should be at that brand-new stadium.”

After an hour in the condo, I was fairly certain that Mr. H and his friends were right. Still, that phone call lingered, continuing to sow doubt. I mentioned this to my host. He said he had one more thing to show me, an item that he hoped would put an end to any remaining concerns.

He placed a piece of paper next to the helmet on the table. It had been stamped by a notary, and it read: I, Jean Gehrke, declare this statement to be true that … Fred Gehrke, my husband, designed the original Rams logo helmet. The “Fred Gehrke 1947” signed helmet was the prototype made for the Rams owner …” I stopped reading, scanning downward, toward the signature and the date: 12.11.20. Mr. H even had a picture of her signing it.

CONFIRMATION OF THE CONFIRMATION

I sent dozens of pictures and videos to Aikens at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He had done his own homework on Gehrke and the helmet, calling Joe Horrigan, the Hall’s longtime historian and the curator before him.

When we connected in May, Aikens corroborated what that signed paper already seemed to lay out. The Hall did have a helmet from Gehrke, but it was smaller and not worn, just like from the photo Gehrke had taken in his office as he recreated his creation. Horrigan told Aikens that he believed a former executive at the Hall was friends with Gehrke and had commissioned the replica for display. “To me,” Aikens said, “this looks like that helmet.” Aikens also believed the paint on the buyers’ iteration more closely resembled the materials available in the 40s. It was less acrylic, not as strong, or as shiny, not absent blemishes—closer, the curator said, to a watercolor-like version that pro football fans see today.

“I can’t imagine this is fictitious,” Aikens said, meaning the buyers’ claims. “It looks to me like the prototype.”

He suggested another round of vetting, to be safe, telling me I should contact Gehrke’s siblings and children, maybe even one famous grandchild, Brewers star outfielder Christian Yelich. I made a list, leaving out Yelich (who’s a tad busy in the summer) and looked up numbers, Facebook accounts, email addresses. Obituaries from when Gehrke died listed six brothers, three sisters and numerous children and grandchildren. In the ensuing two decades, some of those relatives had also passed. Still, I tried to contact one every day for weeks, circling back whenever reaching a dead end.

Five months later, no one has responded.

CONNECTING, PART I

Aikens asked for a conversation with the buyers. He said the Hall had a Science of Football display, and he was looking for artifacts to rotate in. He told me to remind Mr. H that all donations were tax deductible. I set up a call with Mirigian, the boxing character who tied all these various entities—SI, the Pro Football Hall of Fame, estate buyers, Gehrke’s remaining relatives, the NFL and its bevy of logoed merchandise—together.

As they went through the same details, at that exact moment, the story shifted. After all the searches, all the research, all the phone calls returned and ignored, the person who would best know whether the buyers had a prototype—beyond Fred Gehrke himself—was now telling a boxing promoter that his wildest sell sure looked like an unfathomable truth.

“I’m not going to tell you about the history of the NFL,” Mirigian said, before launching into just that, the connection to sports business, all those billions.

Aikens could have said, “You had me at prototype.” Instead, he paused briefly, as if he wanted the gravity to sink in. He wanted to display the helmet, which he called “one of the most significant artifacts in NFL history.”

CONNECTING, PART II

On a Tuesday afternoon in mid-September, Mr. H, Mirigian and friends convene at the Westwood condo. Two days before, the Rams had decimated the Bears on Sunday night, while the players wore new—and much criticized—helmets that feature those famous horns, the design that began with the prototype that Gehrke created more than 70 years ago. Those helmets, of course, had facemasks. The L.A. kickers, naturally, warmed up by booting footballs into nets. They all owed a certain debt to the artist who once donned the same uniform.

The buyers leave early, like really early, riding an elevator downstairs, where Mr. H’s black Cadillac Escalade is parked in the garage. He opens the trunk with a push of a button, and they place the artifact inside, like a newborn strapped into a car seat, then cover it with a blanket.

In Agoura Hills, the Rams business office lobby features a dizzying array of Rams horns. They’re stitched onto throw pillows, emblazoned on helmets, part of the artwork arranged on the walls.

I had wondered how the Rams would react to this piece of history, one I thought tied the franchise in a deeper, more connective way to the larger story of the NFL’s merchandise boom. They already knew. On that previous Sunday, they had played a video inside their palatial stadium, telling the story of their new design, which had been unveiled in 2020, its launch tied directly to the original version and its place in NFL lore.

Kevin Demoff, the franchise’s chief operating officer, noted how the team had collaborated with Nike, seeking innovation that had been encouraged by the NFL. “This new helmet features vibrant colors, a metallic finish and an evolved horn shape,” read the press release. "Our new uniforms preserve the storied legacy of the Rams with the horns at the heart of the design,” Demoff had said then.

Mirigian and the buyers unspool an informal presentation in the lobby. Mirigian asks Demoff if he can relay what they have uncovered to owner Stan Kroenke. Demoff doesn’t hesitate, speeding to his office to grab his phone and sending an immediate text.

A video crew materializes and begins to film. Longtime employees snap pictures. The buyers run through the whole story—of the helmet, of Gehrke’s background, of the wild sequence of events that ties them all together. They show him the Rozelle correspondence, the ring, the drivers licenses, the notarized letter that Jean signed. Mirigian describes Fred as the “MacGyver of the NFL.”

Demoff, who was an art history major at Dartmouth, continues studying the helmet. “Be careful. He might put it on and run out of here,” a colleague whispers.

When he speaks, he says he loves the contrast inherent in Gehrke’s creation compared to the modern world of pro football, where even art can be made via computer and where imperfections are often derided as incomplete, rather than seen as progress. Nowadays, he notes, it would take two years to push that kind of radical change through the NFL’s lengthy process. “I see work-in-progress revisions,” he says. “That’s what’s so cool. Right now, so much of the NFL is so perfect and so regimented. You can see that this work is someone’s vision, that it’s brainstorming.” Those very blemishes, he argues, make the prototype more desirable, “because it shows the human connection to sports, the personalization of it.”

“It’s so cool,” Demoff says.

Mirigian senses an opening. He mentions the empty display case in the lobby and how perfectly the helmet, their helmet, Gehrke’s helmet, would fit. Would the Rams like to display this piece of team history, no charge? he asks. “It has been an amazing journey, and the [prototype] is finding its way home,” he says. “There’s your headline, Greg.”

THE PHONE CALL, PART II

With publication imminent, SI reached out to Jean Gehrke once more. She didn’t sound upset, but she wasn’t budging from her convictions, either. She repeatedly insisted the buyers had a “mini” version of the helmet. I asked how so many disparate entities—from SI to the Rams to the Hall—could look at the same thing and come to an opposite conclusion. Was it possible that this was all one big misunderstanding? “No way,” she said. Now even more confused, I stammered out … so there’s no way this is the prototype? “It’s a mini-helmet,” she said. “I may be hurting myself by telling the truth and not getting a nickel out of anything. But this is not a 1947 helmet.”

Later, while I was on paternity leave, an SI colleague asked Jean if she had a preferred resolution. Was it to undo the sale and get the helmet back? She said no, but that since Welch sold the helmet, she should receive additional compensation. Welch says she told him the same thing when he asked Jean if she wanted him to buy the helmet back and return it to her.

I should be honest here. I felt conflicted, both during our last conversation and ever since. Not about the helmet—not really, less than 1% of doubt remained—but more about the story and its potential impact on Jean Gehrke. I believe—then, still—that the buyers have a piece of NFL history. But whether it’s due to confusion, regret or plain old disagreement, Jean says she believes the opposite. My concern centered more on the stress the story was creating for her, along with our role—my role—in that process.

Desperate, I tried pivoting to Fred during our last call—his life, his legacy. Wasn’t that important? Wasn’t having a reminder a good thing? “He was a very talented man,” she said. “[People] could be reminded of that with or without the [helmet]. The truth is, that [helmet] doesn’t mean a damn thing. I’m sorry. It just doesn’t.”

THE POINT

In that lobby, before the other phone calls, Demoff says he plans to get back to Mr. H and his friends shortly. He says the NFL might want to display the helmet at the Super Bowl in SoFi next February. He even gives the group a version of the latest Rams helmet as a thank you. He wonders aloud if he can build out a new headquarters—the one the Rams have planned to construct for years now—around this artifact that could show pro football’s evolution.

I’m not thinking about the Super Bowl at that moment. I’m not thinking about displays. I’m not even thinking—not really—about this helmet that has come to dominate my life. I’m thinking about Fred Gehrke, sitting alone in that garage. I’m thinking about his life, as a football player, sure, but mostly as an artist.

Everyone and everything around the helmet fades as my mind wanders to a notion I had not previously considered. Perhaps our quest wasn’t about the helmet’s authenticity. Or even about the helmet, period. Maybe it was really about a man with pro football’s most impressive résumé, an eclectic, inventive soul who helped shape what the NFL has now become. If an estate sale and the ensuing debate over its contents can spark this kind of sleuthing, this kind of debate, then Fred Gehrke got what he deserved but never wanted: a reminder of his legacy and why it matters, of his art and what it changed.

Additional reporting by Gary Gramling

More SI Daily Covers:

• Ode to the Disappearing .500 Season

• How Long Can We Play? The Quest to Prolong Athletic Mortality

• The Little Blessings of the Black Widow, Jeanette Lee