The Football Outsider: How Jakob Johnson Is Helping Define the Post–Tom Brady Patriots

Long before he became one of the people most responsible for the Patriots’ post-Tom Brady revival, Jakob Johnson was living in southwest Germany, growing up, as he says, “in the wild” among the ponies, sheep, chicken and geese, living alongside a sister who, at age 7, could deadlift car tires affixed to either end of an iron rod in their yard. His last job before he started listing “Professional NFL Football Player” on his tax return was a member of the wait staff at a tie-dyed pizzeria called “Mellow Mushroom” and his foundational knowledge of football came from YouTube highlights and Wikipedia articles.

Johnson discovered the game as a restless child, rumbling through the fields of his red-roofed village after seeing highlights of Super Bowl XLII, or, as he refers to it, “the one with the helmet catch.” He didn’t know the rules until 2009, when a friend of his secured a copy of Madden with Brett Favre on the cover.

Teachers would send him home with a note for his mom: find better ways to tire him out; his active nature was bleeding into school time. Soccer was not physical enough. Swimming and ice hockey were too boring. But Johnson felt at home with the youth program of the local club team, Stuttgart Scorpions, wearing a Riddell helmet from the early 1990s left behind from the nascent days of NFL Europe.

At the time, Johnson says, the dream of becoming a football player was completely obscure. Now, he returns to Germany and sees kids playing in the same fields wearing Nike Vapor gear and understanding the nuances of defensive coverage that didn’t simply require you to follow a man out of the offensive backfield. His successes (and missteps, like a blown assignment resulting in a blocked punt against the Colts last week) are thoroughly dissected on German Football Twitter.

“[Back then,] it would be like telling someone you were going to become a professional skateboarder or something,” Johnson says.

So his journey to revivalist fullback in a retrofitted Patriots offense, minor international celebrity and centerpiece of the NFL’s International Player Pathway Program, which aims to globalize and diversify the league’s almost exclusively U.S. makeup, came as a bit of a surprise to everyone. Now in his third year, Johnson typically plays on about a third of the Patriots’ offensive snaps. He played almost half in a nearly pass-less, windswept victory over the Bills 16 days ago, in which Johnson made a critical block to free running back Damien Harris for a 64-yard touchdown. He is the fulcrum of their “21” personnel package (two running backs, one tight end and two wide receivers), which they use more than almost any other team in football. He is Pro Football Focus’ second-highest-graded fullback (behind Ravens stalwart Patrick Ricard). Last week, he received a ball from owner Robert Kraft at a press conference, held on his 27th birthday, commemorating his 1,000th snap in the NFL, a benchmark hit by only two other International Pathway players in the program’s history.

Last season, Bill Belichick said that Johnson was among the top five players he’d ever coached in terms of year-to-year growth. Belichick has told friends that he considers Johnson—easily identified by the brightly colored dreadlocks draped over the back of his neck collar—a “tone setter.” Johnson, in turn, has adopted some of his coach’s personality, artfully dodging a question about any difference between the playbook of the Stuttgart Scorpions (which, he says, names plays after random European countries), the last team he played for before coming to the NFL, and the one used by the Patriots.

“I knew what the media wrote about him, what people say,” Johnson says. “Super smart, super intelligent. People always just think he’s mean and mysterious. But [through him] I realized that there is so much more to the game than I was aware of.”

But before any of that, he was alone in his room in Stuttgart, copying and pasting the email addresses of every FBS and FCS position coach in the U.S. into an Excel spreadsheet, hoping someone else might take this vision he’d developed for his life as seriously as he did. At 18, he was recruited by an SEC school only to wash out with a handful of games under his belt. Three years after leaving the University of Tennessee and the country he was rediscovered, given a crash course in the sport’s highest level during a truncated season and, eventually, became an integral part of both the Patriots offense and a league-wide marketing strategy to tap into foreign markets à la the NBA.

It’s too much for Johnson sometimes, who, after receiving the ball from Kraft last week returned to his apartment and wondered: “Man, what if I just wake up tomorrow and I’m back in Germany?”

In the early days of the International Player Pathway Program, started in 2017, Damani Leech, the COO of NFL International, remembered a discussion focusing on the potential for a global scouting arms race across sports. Around that time, the Tampa Bay Rays’ construction of a baseball facility north of São Paulo, Brazil, served as a warning shot across the sporting world, opening eyes to the idea of an organization plopping itself in the middle of a hotbed filled with elite, untapped athletes and giving themselves exclusive permission to train them from the ground up.

Rich McKay, the CEO of the Falcons, told Leech he didn’t want the NFL to fall into a scenario in which the international market became the Wild West, with teams outbidding one another for raw, international talent. Not at that stage of development. It was obvious that the league had been flirting with foreign growth for various reasons, specifically as a way to ensure that the best athletes in the world land with the NFL. The NBA has had All-Stars from France, Germany, China, Nigeria, Greece, Spain, Slovenia and Argentina, and as a result enjoyed an injection of fans from across the world into its league.

The NFL’s goal was to get a similar influx of talent and, with that, the accompanying tailwind of business expansion tied to fanatics in foreign markets obsessing over the product. Its route was a centralized process in which foreign-born players would be identified en masse by a shared service, trained together and allocated throughout the NFL (each year a division is chosen at random to receive one of the small handful of IPPP candidates).

“Step 1 for us is increasing the number of foreign-born players in the NFL,” Leech said last week over Zoom. “Then we want them to achieve that individual success. Rookie of the Year, MVP, Defensive Player of the Year. That’s the next step from us in the evolution of the program.”

Over the past few seasons, the NFL has started to accumulate hits. Jordan Mailata, a starting offensive tackle for the Eagles, signed a four-year contract extension with the team earlier this season, making him one of the 16 highest-paid tackles in the NFL at $16 million per year. The former Australian rugby player is the first IPPP player ever selected in the NFL draft, selected despite never having played a single snap in an organized football game. Efe Obada, now a defensive end for the Bills after a previous life with the London Warriors, was the first IPPP player to log 1,000 snaps in his professional career.

They, along with Johnson, have helped Leech and their team develop strategies on how to gauge their popularity abroad, on top of anecdotal evidence they see firsthand with various coordination from their offices on the ground in other countries. Sandro Platzgummer, an Austrian running back on the Giants, was so flooded with media requests during his first year that the league office coordinated with a public relations liaison from his club team back home to help facilitate interviews.

“We see things in what we try and track from a metrics standpoint, things like jersey sales from NFL Shop,” Leech says. “We compare Jakob’s jersey sales in Germany (No. 5 in the month of November) versus the U.S. in terms of rank. We see he’s overperforming, overindexing. We track social media. The average post on NFL German platform versus a post featuring Jakob. It definitely has an effect.”

Finding a Dirk Nowitzki or Luka Dončić is ultimately the dream, or at least a cemented bridge to a steady foreign pipeline. But the immediate challenges are still real. The NFL, culturally, can be a complete brain scramble for players above and beyond what is experienced in more comfortably global sports like soccer, basketball or baseball. Some who have gone through the IPPP or have mentored IPPP players are still reeling somewhat from the process of leaving home and getting dropped off in a foreign country without the slightest idea of how to operate.

“I couldn’t have a conversation, and then add in that Houston twang from college,” says Sebastian Vollmer, a longtime Patriots tackle and German native who has helped mentor Johnson. “Even if I knew the words I couldn’t understand what they were saying. Then, I finally woke up one day and I remembered I had a dream in English. It’s such a weird feeling when the voice in your head switches from German to English.”

He adds: “I know this is an American story you’re writing, but for a German person, this is unfathomable. There are more people [in Germany] watching these kids than there are at Bayern Munich. It’s hard to understand if you haven’t seen it.”

Leech said they have started developing football slang dictionaries full of random vernacular that players could encounter in the huddle. He remembers hearing from Isaac Alarcón, a Mexican-born IPPP player for the Cowboys, who, while in the huddle with Dak Prescott, had to turn to his side and ask the player next to him: I’m sorry, what?

Taken into consideration, it makes what Johnson is accomplishing all the more impressive. Unlike Mailata, for example, Johnson is not an outsized physical specimen coaches salivate over developing. He is roughly the league-average size for a fullback, a completely replaceable entity considering few teams use one. He was essentially dropped off at football MIT and forced to excel in engineering without any prior knowledge of basic physics. (He said that the Stuttgart Scorpions ran very pared down man and zone defensive concepts that, in the most exotic of cases, asked defenders to backpedal into a coverage area.)

Belichick is notorious for his bottom-of-the-roster churn, exhibiting little patience for players who don’t assimilate. Vollmer knew firsthand that an endearing backstory wasn’t going to buy Johnson any more time.

“On a Wednesday meeting getting ready for Denver, certainly you’re not talking [with Belichick] about Bratwurst and beer,” Vollmer says.

Johnson appeared in just 13 games over four seasons at the University of Tennessee, falling into the meat grinder that often traps players unaware of football culture and the different political pathways to the field. He switched positions. He dealt with injuries. While he says now he has no hard feelings, he found himself spending time between his junior and senior year flying down to Florida to stay at an old high school coach’s house, with the coach offering to spend eight to 10 hours each day on the field with him teaching him how to catch and run routes, vital skills he never learned in college.

He said he didn’t know how to take advantage of what instruction Tennessee’s coaches could offer. He couldn’t grasp basic terms like “pro-style offense” that were thrown around regularly. He was homesick, having been back to Germany just twice in four years, and was completely out of money. He found work at the hippie-themed pizzeria in order to afford plane tickets home for himself and his girlfriend after his pro day ended with no interest.

“Those were definitely weird times,” he says.

He was rescued by the Stuttgart Scorpions, who offered to buy flights for Johnson and his girlfriend in exchange for a season of work in the German Football League. The Scorpions finished that season in dead last, barely fending off relegation into the cellar that is German Football League 2. Johnson tried to help them implement some of Tennessee’s offense, though many of the concepts were too complicated for the club, which, Johnson says, struggled to find adequate resources. Their games were seemingly recorded and streamed online freehand, with the camera sometimes swirling around Blair Witch–style for some kind of comedic effect.

But the experience led to his connecting with the IPPP and earned him one of four spots on an NFL practice squad (which doesn’t count against the team’s total). Johnson trained at IMG Academy, learning how to stand in a receiver’s stance, block and improve his speed. The Patriots were interested in developing an additional fullback behind James Develin, a three-time Super Bowl champion who held the position for most of the previous decade. It bought Johnson a one-year internship in New England, shoving him face-first into the nuances of a game that might have otherwise left him abandoned in Knoxville. His early attempts to locate and execute a block in training camp looked a bit like a Funplex employee trying to catch fastballs from the speed pitch in the batting cage.

“Situational football is something that I’ve never been exposed to, but the amount of detail and thinking related to every situation that could come up, it’s something I’m going to take with me,” he says. “If I get a chance to coach some German kids, it would be something I’d be sure to teach them along the way.”

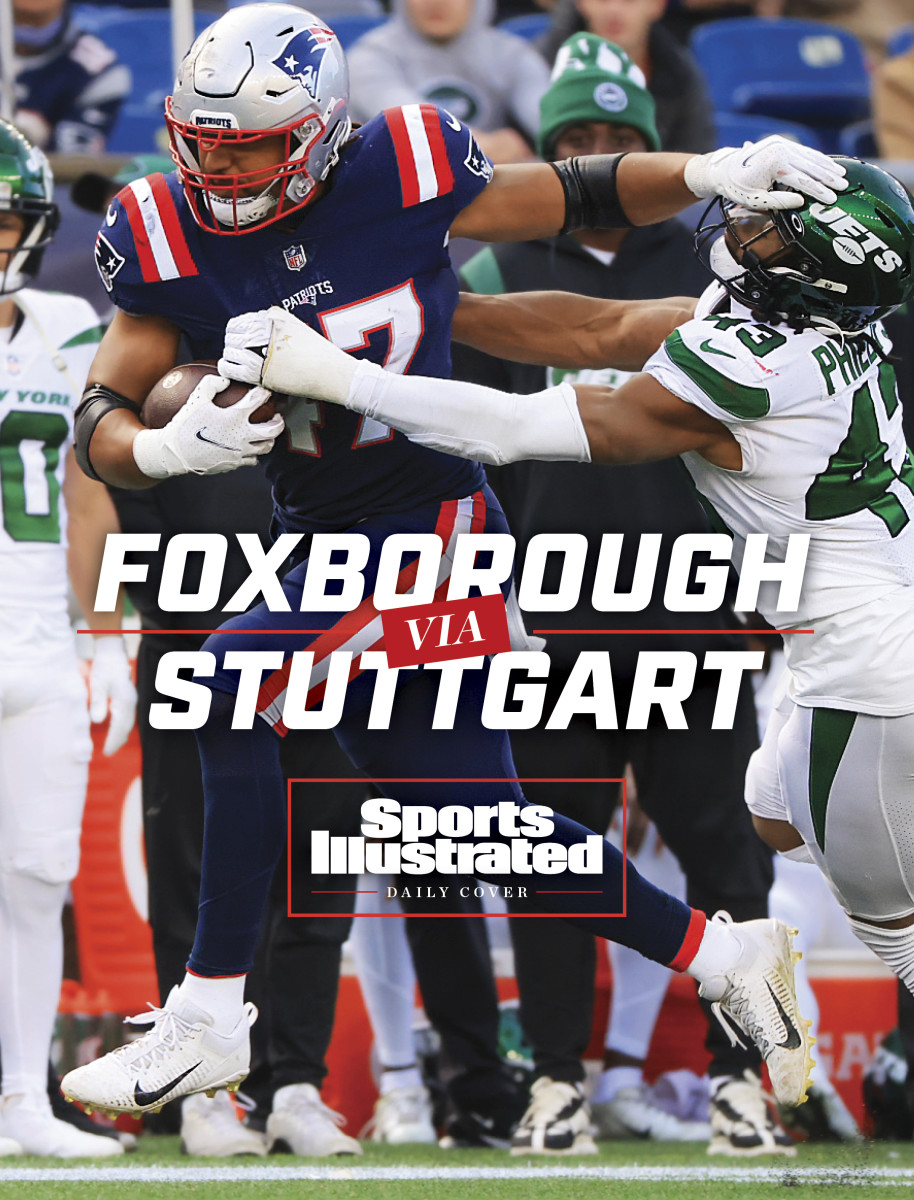

In 2020, Johnson got promoted, earning the role of Cam Newton’s personal battering ram. He showed up in Patriots film in the form of a few explosive collisions, flying dreadlocks and a handful of catches secured with two hands, Johnson trapping the football like a child trying to keep a bubble from popping. In ’21, entrenched as a starter, the Patriots layered more nuance into their 21 personnel set. Johnson has lined up as a wide receiver, a slot receiver and a tight end. According to NFL GSIS statistics, he provides more net yards over average on Patriots rushing plays than any other blocker save for tackle Trent Brown.

On a Wednesday afternoon a few weeks back, while sipping a cup of coffee, Johnson laughs when asked about his future, as if getting to this moment, navigating this strange trip, wasn’t enough. He’s thankful his girlfriend likes Germany. He’ll go back someday.

For now, he’s finally able to bring his worlds together. In America, he appreciates the portion sizes of meals, though he’s hoping to find a connection for fresh produce reminiscent of what he was able to enjoy in the German countryside (we are “slowly but surely trending in the right direction” on the organic-food front, he says). He finally looks comfortable playing a game that for so long felt cold and inaccessible. He finally feels at home, which is more than enough.

• 2021 Sportsperson of the Year: Tom Brady

• From Chile to the NFL: Sammis Reyes and the Path Never Taken

• A Quarterback Evolution and a Coaching Revolution