The NFL’s First Real Foray Overseas, 30 Years Later

As the halftime performers burst from the tunnel at FC Barcelona’s Camp Nou, clad head to cleat in what must’ve seemed like modern gladiatorial garb—full pads, white jerseys, green helmets each with green face mask and a fiery dragon logo—a murmur of confusion spread through the La Liga crowd. “They were all looking around like they didn’t know what was going on,” Louie Aguiar says.

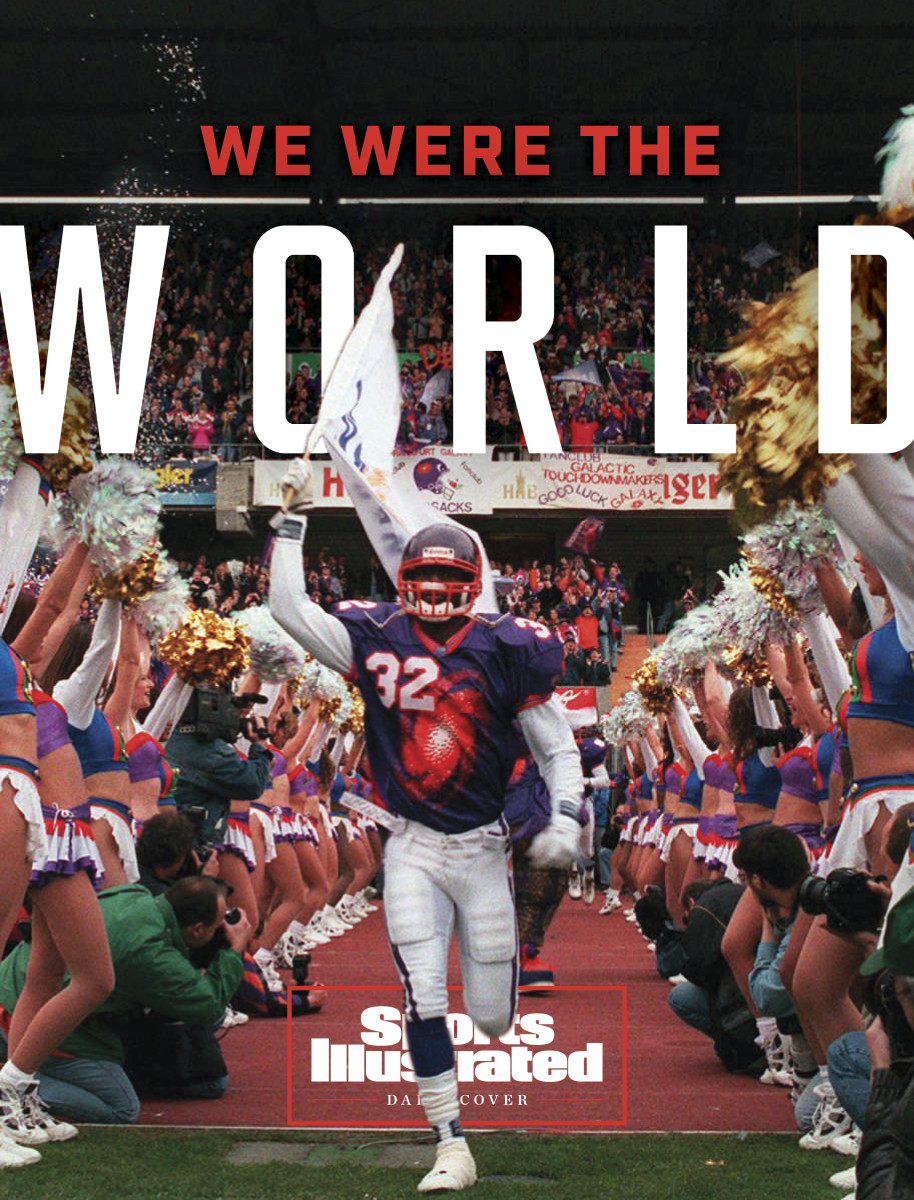

Down on the soccer pitch, the feeling was mutual. Aguiar and his fellow Barcelona Dragons had been dispatched by team officials to generate buzz for their debut season opener in the startup World League of American Football. The players spent five or so minutes scrimmaging at practice speed while a stadium announcer spelled out various gridiron terms in Spanish. No matter what long pass or power rush the Dragons dialed up on that Sunday night in March 1991, though, fans responded with little more than tepid applause … at least until Aguiar stepped out to punt.

“The place just erupted,” recalls Aguiar, then 24 and a few months away from the start of a 10-year NFL career. “All the guys looked at me like, ‘Why are they so happy?’ I said, ‘They understand me kicking the ball. They don’t understand you guys that are 6' 8", 300 pounds, running around in these tight uniforms.’ “

Three decades later, the WLAF—an unprecedented transatlantic spring experiment spanning five countries and two continents—mostly stands as a historical footnote beneath a long list of NFL-backed efforts abroad. Look at the landscape today: Three German cities are jockeying to join the U.K. and Mexico in hosting regular-season games as soon as next fall. Nineteen NFL teams are bidding on league-issued marketing licenses in Brazil, Australia and China, among other places. And international expansion continues to provide an evergreen talking point, no matter how unlikely the actual prospect.

Still the 10-team World League, as it’s alternately known, remains relevant for many reasons. Launched amid widespread skepticism, not to mention an overdose of punchlines from sports columnists involving an acronym that evoked a comedy radio station, the WLAF succeeded in bringing lasting innovations to the pro game; fueling the careers of future NFL coaches; and serving countless new fans with a unique slice of Americana best summed up by a series of promo billboards seen throughout Frankfurt, home of the Galaxy: “Come Watch 11 Men and Their Egg.”

Above all, though, the inaugural 1991 season of the WLAF endures as an unforgettable memory for the many players, coaches and staffers who formed its three pioneering European clubs: the Dragons, the Galaxy and the London Monarchs. For it was they who made the exhausting road trips, who mingled with the soccer-crazed locals, who withstood the lacking football infrastructure to lay a footprint for the future.

“It’s an incredible story of the NFL’s first foray overseas, where we truly built the plane while on the tarmac,” Dragons general manager Andrew Brandt says. “It was not just a job, but an adventure.”

On July 19, 1989, the NFL’s 28 team owners gathered at a hotel in a Chicago suburb for a high-stakes, closed-door meeting. Much of the next nine hours was devoted to addressing the grievances of 11 members who, frustrated with their lack of involvement in the selection process, had conspired to block the election of commissioner Pete Rozelle’s intended successor, Jim Finks. But the group also came together long enough to overwhelmingly approve the formation of what Patriots owner Victor Kiam touted as “a global league.” Initial plans called for a dozen franchises: six in the U.S., and one each in Mexico City, Montreal, London, Barcelona, Frankfurt and Milan.

Leading the charge was WLAF president Tex Schramm, the longtime competition committee czar whose 30-year tenure atop the Cowboys front office had met its recent end when an Arkansas oil tycoon named Jerry Jones bought the team for $140 million and fired Schramm’s longtime ally, coach Tom Landry. (Schramm waited for the sale to become official before resigning.) This wasn’t some cushy retirement project either; earlier that summer Schramm had set out on a whirlwind barnstorming tour through both continents, drumming up interest in possible host cities. “I’ve been moving so much I’ve been saying danke schoen in France and gracias in Germany,” he told reporters outside Chicago.

By then the NFL was already busy exporting its business—notably to Britain, where highlight packages aired every Sunday evening on Channel 4, annual merchandise sales were projected to hit $50 million, and some 200 teams competed in amateur leagues. But while the league also staged semi-regular preseason games in London, Montreal and Tokyo, these were baby steps compared to the giant leap across the pond that Schramm envisioned, going where no football startup—see: the USFL and the International League of American Football, which folded in April 1990—had before.

“American football deservedly has an audience around the world,” wrote a New York Times columnist, “but until those countries produce home-grown players, the N.F.L.'s spring league will be nothing more than a marketing ploy, a second career for Tex, with a typical whiff of football arrogance.”

A whiff? Schramm wore his bold goals like bad cologne. “He said, and I’ll never forget this, ‘The World League is going to be bigger than the National Football League,’ ” says then-ABC broadcaster Brent Musburger, recalling an exploratory meeting that he and color analyst Dick Vermeil had with Schramm. “I didn’t know whether to laugh there. I was stunned.” Ultimately, though, such confidence led to Schramm’s downfall when he was ousted in October 1990. As Sports Illustrated reported the decision, “Schramm wanted the WLAF to be the big leagues and the NFL wanted Double A ball.”

And so Schramm found himself sitting on his fishing boat that winter when the WLAF announced its final launch plans under new commissioner Mike Lynn. Milan and Mexico City had been scuttled, leaving seven North American and three European teams that would kick off in spring 1991. Franchise fees of $11 million would foot the majority of bills, but 26 of 28 NFL owners—Chicago and Phoenix chose not to participate—also forked over $50,000 apiece, a sizable safety net when paired with the multiyear, million-dollar rightsholder deals inked by ABC and USA. (An all-star cast of NFL players, featuring Dan Marino, Boomer Esiason and Warren Moon, were later hired as color analysts.)

Then there were the World League’s various riffs on NFL canon, all together geared toward luring that elusive spring football audience. Some were rulebook matters: The play clocks would be shorter (25 or 35 seconds instead of 45), teams could attempt two-point conversions (at the time allowed only in high school and college), and on-field celebrations were declared legal. Others were technological, such as quarterback-coach radios and a helmet camera that captured first-person footage for TV, à la the GoPro.

Behind the scenes, front offices soon filled up with rising industry stars: former NFL quarterback Oliver Luck, 30, the Galaxy general manager; Michael Huyghue, 29, credited as pro football’s first Black GM in Birmingham; and Brandt, 32, then working as a player agent. “I remember Mike Lynn giving me this whole sell job, that we were going to spread American football around the globe and be huge,” says Brandt, now a sports law professor at Villanova (and regular SI contributor). “I decided, Why not?”

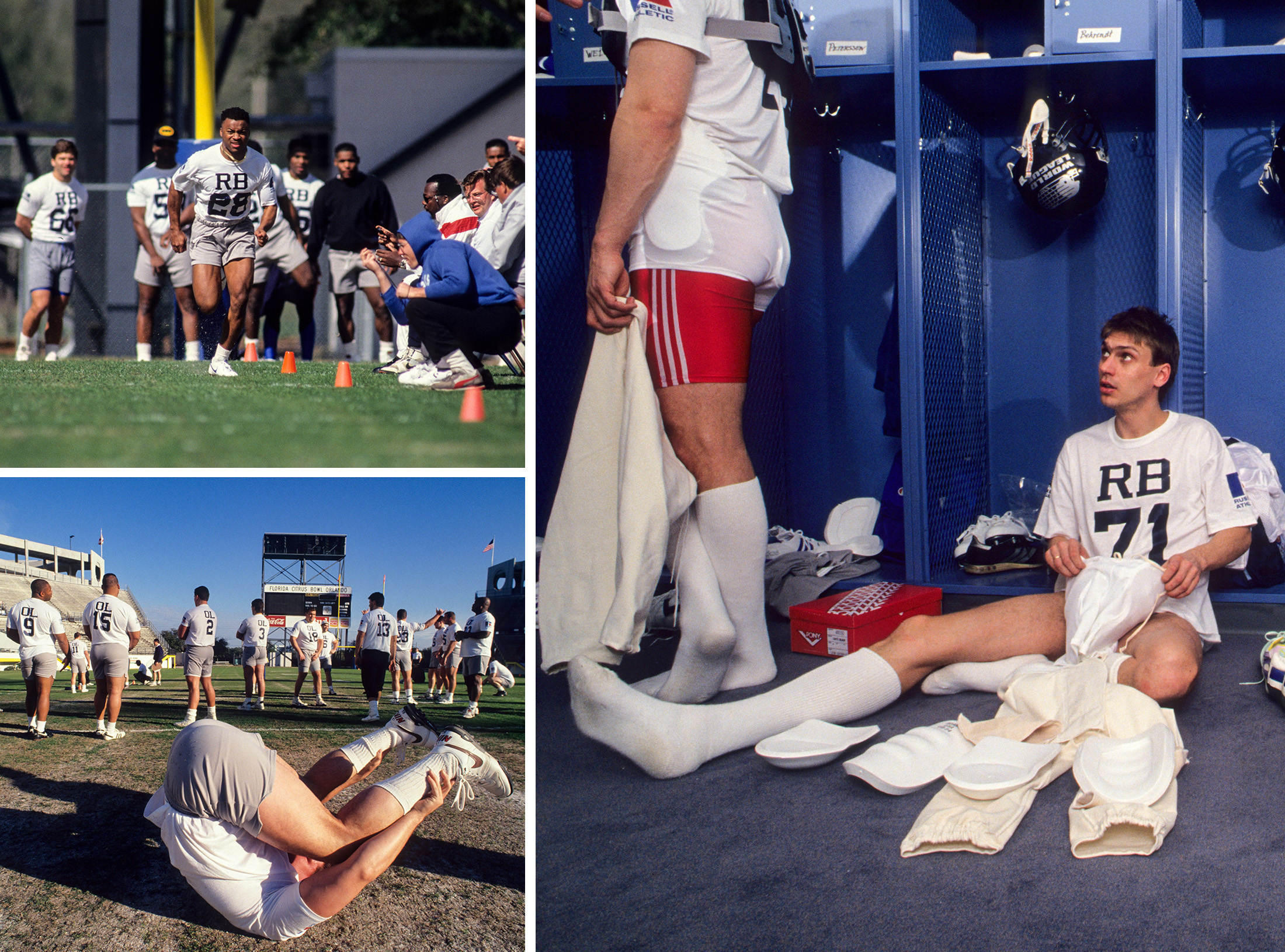

The sidelines, however, were stuffed with what SI described as coaching “retreads”—Frankfurt’s Jack Elway, father of John; Barcelona’s Jack Bicknell, late of Boston College; and London’s Larry Kennan, who was coming off a stint as the Colts’ offensive coordinator—a side effect of the WLAF’s difficulties luring young talent from the NFL ranks. Rosters, however, had more global flair thanks to the World League’s talent search program, Operation Discovery, which mandated that each team field four players from a pool of 40-plus soccer players, ruggers, sprinters, boxers, wrestlers, javelin throwers and other world-class athletes who had pivoted to semipro American football abroad.

Along with 650 American players, ranging from undrafted rookies to washed-up veterans, these international prospects were invited to Orlando for the WLAF’s combine and position-by-position draft in February 1991. Base salaries were modestly capped ($25,000 for quarterbacks, $15,000 for punters and kickers, $20,000 across the rest of the board) to prevent the sort of lavish spending that toppled the USFL. But even attractive individual and team bonuses was less of a carrot for many Americans than what the World League offered in the abstract. “Everyone was looking to do the same thing and get to the NFL,” says London quarterback John Witkowski, a sixth-round pick of the Lions in ’84 who left his sales job to sign up. “That was the golden ring at the end: a chance to showcase your skills.”

At the same time, the prospect of shipping out proved daunting to many who were picked by the European teams. For starters a chaotic preseason schedule loomed after the draft, requiring players to stick around in Orlando for two weeks of domestic training camp before flying straight to their new cities. “Had to pack everything,” Greenwood says. “Once you made the team, you never went home.”

And then there was the uncertainty of what awaited them when they arrived. “I was a little dismayed,” says Monarchs running back Judd Garrett, who joined the World League alongside brothers John and Jason, all of whom learned about the opportunity when info packets were mailed to the family’s central Jersey home. “Nothing against London, but I didn’t want to go. I didn’t know if we’d have any people go to the games. I didn’t know if people even knew what American football was there.”

Stan Gelbaugh was out of football in early 1991, selling photocopiers around the Washington, D.C., area and hating it. Then the career backup quarterback got a call from an old Bills teammate, Jim Haslett, who had joined the WLAF’s Sacramento Surge as an assistant coach, asking if Gelbaugh wanted back in the game. “Hell yeah,” replied Gelbaugh, despite admittingly knowing “nothing” about the new league itself.

A few weeks later, Gelbaugh was caught off-guard when the Monarchs, not the Surge, selected him in the WLAF supplemental draft. (Officials had realized rosters were thin on talent and deputized coaches to find players for a communal pool.) But he found comfort in a passing familiarity with London, having appeared in the inaugural American Bowl at Wembley Stadium as a Cowboys rookie in ’86. “That was really cool to come back,” Gelbaugh says. “Understood the difference between a pound and a dollar.”

Not everyone so eagerly embraced the cultural differences. “When we first got there, there was almost a revolt over the more European-style food,” Monarchs offensive coordinator George Warhop says. “And we’re big men, going over to an environment where people didn’t eat as much as we ate.” Meager rations were a similar problem at the Barcelona hotel where the Dragons were living. “Their servings were at 9:30 p.m., so we paid for an extra serving at 6:30, and they never had enough,” Brandt says.

Accomodations left much to be desired, too. Dragons CEO Jack Teele once recounted booking practice time on a soccer field outside Barcelona after meeting the land’s owner in a local tavern and buying three rounds of drinks; Brandt describes rounding up night tables and pillows to put at the ends of hotel beds so his taller players wouldn’t slip off. Over in Frankfurt, the Galaxy rode two and a half hours round-trip from their Best Western each day, stopping in the middle at a separate facility to dress and hold meetings. “We ought to be sponsored by Trailways,” quarterback Mike Perez quipped to SI.

The Monarchs didn’t have it much easier, bunking on the campus of a once-masonic boys school known for serving as a popular filming location for British murder mysteries. Meetings were held in cramped classrooms, or otherwise what Garrett remembers as a “garage-type thing.” Practices took place atop a swath of steadily sloping pasture behind the cafeteria. Players were divided into two dorms: one freshly renovated with working A/C and heat, the other so dingy that some dubbed it the Slums, or the Ghetto. (At least the food issue was resolved. “They brought in a chef, and all of a sudden we’re eating a little bit more pancakes for breakfast, steaks for dinner, bacon cooked American style,” Warhop says. “Just some of the things that had to happen to make it a better experience.”)

Equally difficult as installing a playbook and developing chemistry under these conditions was the task facing Brandt and his front-office counterparts. Local television deals figured to be instrumental in helping the World League reach potential new audiences. but promo ads and postgame highlight shows alone weren’t going to fill the teams’ Olympic-sized home stadiums (Wembley, Barcelona’s Estadi Olímpic de Montjuïc and Frankfurt’s Waldstadion). And to sell seats, teams had to sell football.

Perez recalls making a slew of public appearances to promote the coming season, including on U.S. military bases and at a luncheon with Frankfurt business leaders. London brass went the publicity stunt route, inviting rugby legend Ellery Hanley to suit up one practice at running back. “He ran through the middle, and no one was supposed to hit him, but one of our players lit him up,” Gelbaugh says. “The guy’s agent came running on the field, cussing at us. [Hanley] didn’t care. I think he actually wanted to see what it was like.” The team also received a royal boost when kicker Phil Alexander, a former soccer pro who joined the WLAF through Operation Discovery, was invited to a meet-and-greet with Princess Diana. “I shook her hand, said hi,” Alexander recalls. “She was lovely. The paper had a nice picture of us together, and a headline that said, ‘Monarch Meets Monarch.’ ”

Where curiosity might’ve driven new fans to snag single-game tickets, team officials banked on the game day experience bringing them back. “I said, ‘We’re going to sell three hours in America. That’s what they want,’ ” Brandt explains. For the Dragons this meant importing “thousands of pounds of hot dogs and hamburgers,” along with 80 of 180 members of the Central State University Marching Marauders band. (“That’s all the new league could afford,” one report noted.) In London auditions were held for the Monarchs’ cheerleading squad, the Crown Jewels, who performed clad in star-spangled Wonder Woman costumes. And when the Dragons hosted the Monarchs in the first-ever World League game, after the Galaxy had taken the field beneath a shower of fireworks, the kickoff was delayed 14 minutes while the commissioner Lynn landed at midfield in a helicopter to deliver the game ball.

Opening weekend produced a spectacle stateside, with the Beach Boys booked for Sacramento’s home date with the Raleigh-Durham Skyhawks, and 53,000 in Birmingham hearing Jerry Lee Lewis perform “Great Balls of Fire” before the Fire hosted the Montreal Machine. The action, however, was less impressive: In the first quarter of London’s eventual 24–11 triumph, the Monarchs gained a single yard and ceded the first points of the World League when Judd Garrett was dropped for a safety. “Running off the field, I was like, ‘Was this a really good idea to come to this league?’ ” Garrett says.

The WLAF’s hyped technology didn’t quite work as expected, either. While the half-dollar-sized helmet cam provided unique footage from its perch behind players’ right ears, the setup was also criticized as clunky, between a two-pound battery pack and connecting cable that ran down the back of the jersey. The supposedly transformative radio system hardly fared better. “Jack Elway’s trying to call the plays over the radio,” Perez says, “and I’m picking up an air traffic controller trying to land a plane.”

But there were also glimpses that the sport was starting to gain a foothold. The next day, despite a torrential downpour when Barcelona hosted the New Jersey/New York Knights, nearly 20,000 streamed through the stadium gates, grabbing brochures that explained the fundamentals of football, and stuck around to roar in celebration of a 19–7 win. “By the second half, it seemed like everything made sense to them,” Bicknell raved to the Times. “I didn't think I was in Barcelona. I thought I was in the States.”

Then again, not everyone caught on so fast. “The fans cheered at the funniest things,” Gelbaugh says. “You’d throw a long ball that was incomplete, they might cheer for 45 seconds, just ’cause they thought it was cool.” In early April 1991, a couple weeks after their halftime cameo at the FC Barcelona game, a handful of Dragons players, including Aguiar, were invited to attend the Torneo Godó tennis tournament, now known as the Barcelona Open. There Aguiar, an avid tennis fan since childhood, was thrilled to be chosen to meet Boris Becker and present the German star with a diplomatic gift. “I don’t know how I got the football,” Aguiar says, but he still can see the flicker of recognition that crossed Becker’s face upon receiving it.

“He goes, ‘Oh, you’re the ones who play with the egg.’ ”

These days, the simple act of bringing an NFL team to London requires staggering logistical effort. For their Week 5 meeting with the Jets in October, for instance the Falcons’ stashed 7,000 pounds of equipment under their chartered plane, aboard which sat a 150-member traveling party, to go along with an additional 20,000 pounds of essentials already cruising across the Atlantic.

Trips in the WLAF involved far less freight, not to mention far less comfort. Everyone rode commercial on Delta, a league sponsor, leaving skill position players wedged among linemen. “Jack Elway would pick players of the game, and [they] would go to first class on the way back,” Greenwood says. “You wanted to get recognized. But you also wanted that seat up front.” And even though team manifests were small—fewer than 40 players, plus 10 or so coaches and support staff—it often wasn’t possible to fit everyone on the same plane. “A road game was, ‘You six guys on this flight, you [get] 12 on this, and we’ll all meet up and go to work,” former Monarchs cornerback Danny Crossman says.

With the World League’s scattershot geography, heading overseas was especially nightmarish. After their season-opening loss to the Monarchs, Perez and the Galaxy embarked on what was then reported as the longest road trip in U.S. pro sports history, going from Frankfurt to San Antonio (home of the Riders) to the Knights’ Giants Stadium in East Rutherford, N.J., to Sacramento before returning to Germany. Three weeks later they returned with two wins, a loss and, for some, lighter wallets.

“Guys used to gamble and play cards,” Perez says. “I remember one time these two ladies joined in for this high-low game called In-Between and just beat the pants off them.”

Indeed, so much time on the road came with its share of pitfalls.“The trainers would give sleeping pills to us during the flights, so you’re completely out,” Garrett says. “Guys would draw mustaches on each other.” But the sprawling schedule also afforded homesick players extra time stateside; upon starting their epic three-week sojourn, Galaxy tight end Chad Fortune recalls going “to the first place I could to get a big ol’ pile of nachos,” he says. And it fostered a tight-knit environment that several former players fondly compared to their college days. “We ate together, we slept together, we played cards together, we drank on the airplane together, we were together 24/7,” Aguiar says.

Back in Europe, a similar relationship was blossoming between teams and locals: After two weeks on the road in late April 1991, capped off by a 24-hour flight that touched close to 9:30 on a Sunday night, the Dragons were reportedly greeted at Barcelona Airport by 200 shrieking fans; another 1,000 awaited outside their nearby hotel, where a drum corps performed and fireworks shot into the late-night sky. Thousands of U.S. troops stationed in Frankfurt, meanwhile, provided Galaxy players with refreshing reminders of home. “I know it’s a big soccer country, but they actually embraced us from day one,” Greenwood recalls. “They set us up with families at the Army base who’d take us to the [post exchange] to get stuff we needed: food, electronics ... I remember buying a radio over there.”

Where attendance flagged in the States despite the best efforts of marketing departments—before the Monarchs visited the Fire, according to the Los Angeles Times, a horseback rider sped through Birmingham’s streets hollering, “The British are coming!”—expectations were exceeded in all three European cities. There, fueled by hourslong tailgates that Perez describes as “full-notch concert and party mode,” diehards stood nonstop while singing, dancing and waving banners. (“Sex, Dragons and Rock and Roll,” read one in Barcelona.) At times, though, the fervor went too far; Frankfurt kicker Stephan Maslo, a native German and local favorite, recalls returning to his locker after the opener and discovering that someone had snuck past security and swiped the No. 7 Galaxy jersey from his stall. As backup uniforms were considered a superfluous expense, Maslo was forced to switch to No. 9 for the rest of the year. Besides, he says, “We were going on a 20,000-mile road trip, and there was no time.”

But the biggest party was reserved for the wake of London’s victory in the World Bowl. Preseason betting favorites at 5–2 odds, the Monarchs had romped through their 10-game schedule, winning nine with an edge that sparked the occasional post-whistle brawl. “Oh, it was a violent group,” Warhop says. The offensive line, led by center Doug Marrone, was nicknamed the Nasty Boyz and made appearances in British TV commercials. The receiving corps, aka the Bomb Squad, hauled touchdowns from Gelbaugh, the league’s offensive MVP, and delighted fans by hurling the footballs into the stands. “Even though they are charged $100 for each of the balls,” SI noted.

Despite finishing atop the WLAF standings—followed by Barcelona (8–2) and Frankfurt (7–3), with no American team above .500—the Monarchs were sent on the road to Giants Stadium for the playoff semifinals. “In our minds, the NFL wanted New York to be in the World Bowl,” Warhop says. But they fought off the jet lag and, thanks to a career-high 391 yards and five scores from Gelbaugh, emerged with a 46–26 win.

A week later, with actor John Cleese and the Moody Blues watching from the royal box at Wembley among 61,108 strong, London blanked the Dragons, 21–0, behind three interceptions from Crossman, who captured MVP honors and a gift of a Pontiac Transport (and a gift of a Pontiac Transport, which he negotiated a deal to sell). As time expired players sprinted around the field in celebration, slapping fives with fans, before heading to the royal box to receive the WLAF’s 40-pound, light-up, glass globe trophy. "The atmosphere in the stadium was electric,” London offensive lineman Paul Berardelli told SI amid the din. “It was very close to sex.”

From there everyone migrated to a Budweiser-sponsored party at London’s Hard Rock Cafe, where Gelbaugh was surprised to encounter a familiar face. Five years earlier, not long after the ’86 American Bowl, Gelbaugh had stood in the office of Cowboys coach Tom Landry and received the crushing news that he had been waived. Now, basking in the glow of his greatest feat, he once again shook hands with Landry, a minority owner of the San Antonio Riders who was attending the World Bowl with some powerbroker friends, Lynn, Schramm and Rozelle. The words still bring chills to Gelbaugh today.

“He goes, in the little group we’re in, ‘Shows you how smart I was, cutting this guy!’ ”

A few months later, in October 1991, NFL owners again emerged from a long, private meeting with major World League news. “A big hit in Europe, a big miss in [the U.S.] and a surprising success on the field,” as The News Tribune columnist John Clayton described it, the WLAF had reportedly lost $7 million in its debut campaign while delivering bottom-barrel TV ratings that an ABC spokesperson dubbed “very disappointing.” And yet a majority of shareholders voted to keep the project alive, agreeing to contribute an additional $25 million over the next three years, with ABC and USA also renewing their broadcast deals through ’94.

Instead, soon after Sacramento captured the ’92 World Bowl the NFL suspended the WLAF, citing a need to reevaluate its overall international strategy. A year-long hiatus followed, out of which emerged a six-team, single-continent developmental World League that eventually rebranded as NFL Europe, and then NFL Europa, before commissioner Roger Goodell shuttered it for good in June 2007. That same year Wembley hosted the Dolphins and Giants in the NFL’s first-ever game outside North America.

Today the World League lives on through its many alumni working throughout the sports world. Marrone, Haslett, Jason Garrett, Monarchs running backs coach Hue Jackson, and Dragons quarterback Jay Gruden all went on to lead NFL staffs. Fortune became a professional wrestler and monster truck driver. Alexander is CEO of the Premier League’s Crystal Palace. Galaxy guard David Diaz-Infante won back-to-back Super Bowls with the Broncos and now oversees the Chargers offensive line. And when the Jaguars beat the Dolphins on a last-second field goal in Week 6, it marked a dramatic 30th anniversary reunion for Crossman and Warhop, respectively Miami’s special teams coordinator and Jacksonville’s offensive line coach.

“That was probably the most fun football I had the pleasure of being a part of,” Warhop says.

As with many groups unable to assemble in-person during the pandemic, the rest of the Monarchs settled for holding several Zoom reunions in 2020, with 25 or so players and coaches attending each one. “We fell right back into the trash talk,” Gelbaugh says. “Funny to see guys with gray beards.” Maslo led a similar effort among former Galaxy teammates from his current Frankfurt home, unearthing boxes of newspaper clippings and VHS game recordings from the ’91 season, which he uploads and sends to anyone who asks. Aguiar keeps in touch with about 15 Dragons on a text thread where they reminisce about the mid-flight card games and beverages. “We became very close during that short amount of time,” Aguiar says. “Those are great memories I never got anywhere else.”

In many of these cases, players were put in touch by someone who never took a snap, never set foot on a field, and never even attended a game. And yet Chris Blaine is perhaps the ultimate testament to the World League’s pull. Fueled by a ceaseless fascination since the late ‘90s, the 51-year-old art teacher from Rochester, N.Y. has amassed what is assuredly the world’s largest collection of WLAF memorabilia—among it 300-plus jerseys, 100-plus helmets and an owner’s cowboy boots. Once he paid $1,000 on Germany’s eBay for a box of gear sold by a former equipment manager; another time he received a cold call inviting him to drive to Giants Stadium to fetch the Knights’ goal post pads for free. (They’re now in his basement, along with everything else.) He also managed to track down Maslo’s lost No. 7 jersey, delivering it in person on a trip to Germany. “I have it framed in my sports room,” Maslo says. “I’m more than grateful he made this happen.”

Blaine still trawls for World League treasure; top targets include one of the original helmet cams and the World Bowl trophies from the ’91 and ’92 seasons. (“They’re gone,” Blaine says of the latter. “Even the top people don’t know where they are.”) But much of his energies are spent maintaining his exhaustive World League website and finishing a book about the World League that he plans to self-publish, having interviewed 300-plus players, coaches and other former employees thus far. It was through this research that Blaine also became a hub for WLAF contact information, allowing him to reconnect dozens of long-lost teammates. “Chris hooked us up,” Aguiar says. Which is why, even if his book doesn’t sell a single copy, he says, the deep-dive will have been worth it.

“I’m not tooting my own horn, but people say I’m like the caretaker of their history,” Blaine says. “My wife doesn’t get it, my friends don’t get it. But when I get a text from a guy that’s like, ‘Hey man, my kids don’t believe I played football when I was younger,’ and I have almost all of the games digitized in a file, so they can download it and show their family … Yeah, it’s a hobby, but when I tell people what I do and the stuff I have, it’s like, ‘Woah dude, that’s not only nuts, but it’s also really cool!’ ”

A similar conclusion came to Crossman last month. Surveying the countryside behind the Dolphins’ lodgings at Ware’s Hanbury Manor—a converted 19th-century estate on 200 acres of rolling hills, stout pine trees, a par-72 golf course designed by Jack Nickalus II, and a full gridiron that the hotel built for this season to better accommodate its annual NFL guests—the 54-year-old found himself transported to the sloped pasture and the spooky dorms, half an hour away, that the Monarchs once called home. “It wasn't Hanbury Manor, I can promise you that," Crossman says. “[But] just being in a quaint, small setting over there, playing American football, your mind goes back to the people, the experiences, the good times.”

Which is why the first World Bowl MVP counts himself among those cheering for the NFL to expand to London. "I'd love to be part of the first staff of a team," Crossman says. "That'd be fabulous." Few know as well as him the adventure that would await.

More Daily Cover stories:

• Tales From Tom Brady’s Forgotten Rookie Year

• Mystery and Controversy Surrounding the Original Rams Horns Helmet

• How a Women’s Football Team Took Control Away From the Men