In Reshaping the Rules, Have We Written Devin Hester—or Future Hesters—Out of Football?

Devin Hester’s preternatural ability as a return man was evident long before anyone ever actually kicked him a football. You know when you’re playing a schoolyard game and one team transfers possession by throwing it deep? Well, those were the rules back when Hester was 6 or 7, playing with friends, and carving his way through opponents “just came natural to me from that age,” he says.

If a game had five throw-offs, he’d run four of them back for touchdowns “with ease,” he remembers. “It was crazy. We were playing two-hand touch.”

Thirty-odd years later, the greatest return man in NFL history is on the other side of his playing days. Five years removed from his final snap, Hester is now eligible for the Pro Football Hall of Fame, and he (and 14 other finalists) will learn his fate Thursday, in the lead-up to Super Bowl LVI in Los Angeles.

It is a well-worn cliché to consider a skilled athlete in retirement and muse that we may not see anyone like them again. In this particular case, though, it might actually be true.

Thanks to changes in the sport that made him a household name, there may never be another Devin Hester.

Team Spectacular is decked out in gray jerseys littered with red stars and a gradient that flows into bright teal sleeves and pants. It’s June, and in Winter Park, Fla., the high-80s temperatures feel closer to 100. Fans have erected portable tents to shade their seats on the metal bleachers as they watch the Elite Talent All American Summer Showcase, a series of six youth football games starting with U-6 in the morning and ending with U-11/U-12 in the afternoon.

The most spectacular athlete on this particular U-7 squad has the words ANKLE BULLY markered on a strip of tape and plastered across his jersey name plate. He may be preparing to enter fourth grade, but he’s already known nationally and will later share highlights from this game to his thousands of followers on Instagram. He also has quite a pedigree.

This is Father’s Day, and Devin Hester is on the sidelines, as he usually is these days, coaching his son Drayton. Devin wears a white T-shirt, shorts and brown flip-flops, plus two thick gold chains, one of them dangling a goat pendant. (The animal, not the acronym.) But here, Dray, as the aforementioned ankle bully is known, really is the sensation. Every few months a clip will go viral, the skinny lightning bug juking some hapless schoolchild out of his shoes. And because of the last name, the clips get scooped up on blogs and dissected on ESPN.

“The stuff that he does at this age … I didn’t see that type of success till I got to college,” his dad says. “I never played in big games growing up. These showcase games—big tournaments where you have the best of the best—and he’s making plays against the elite talent.”

In short, Hester understands that he has a potential prodigy on his hands.

Outside of this event, in the fall, Hester is the head coach of Dray’s main team in the Florida Elite league. But today, with Team Spectacular, he’s a volunteer assistant. There’s actually a bit of a controversy around it all. Dray switched teams the day before the game because of a dispute with his original coaches. Devin says the old team was planning to play his son only on defense. That’s why Dray taped his nickname over another kid’s borrowed jersey, on a team that is happy to start him at quarterback. Never mind that before today he’d never practiced with them. In warmups he executes a few designed runs out of shotgun, plus some fake handoffs and deep passes; the game will go fine.

As the day unfolds, Devin Hester is the local legend coaching receivers to get wider on outside running plays and reminding them to keep their mouthguards in. He’s also the most decorated water boy in the central Florida youth football circuit, running onto the field to provide hydration relief during breaks.

Dray, too, is versatile: He’s both a free safety and quarterback. On defense, Devin yells from the sideline to let his son know whether he thinks a run or a pass is coming. On offense, one coach stands on the field to help the kids in the huddle, and Devin finally gets his chance to call plays late in the second half.

In the end, Team Spectacular wins in overtime, after which Devin runs onto the field and makes a beeline for his kid. Dray takes off his helmet and puts on a pair of sunglasses as father and son snap a selfie together at midfield. After the game, the two teams will join for a ceremony where the winning players receive rings and Dray is named Most Outstanding Player.

“Florida football, baby,” Hester barks as he walks off the field with his son. “Nothing like it.”

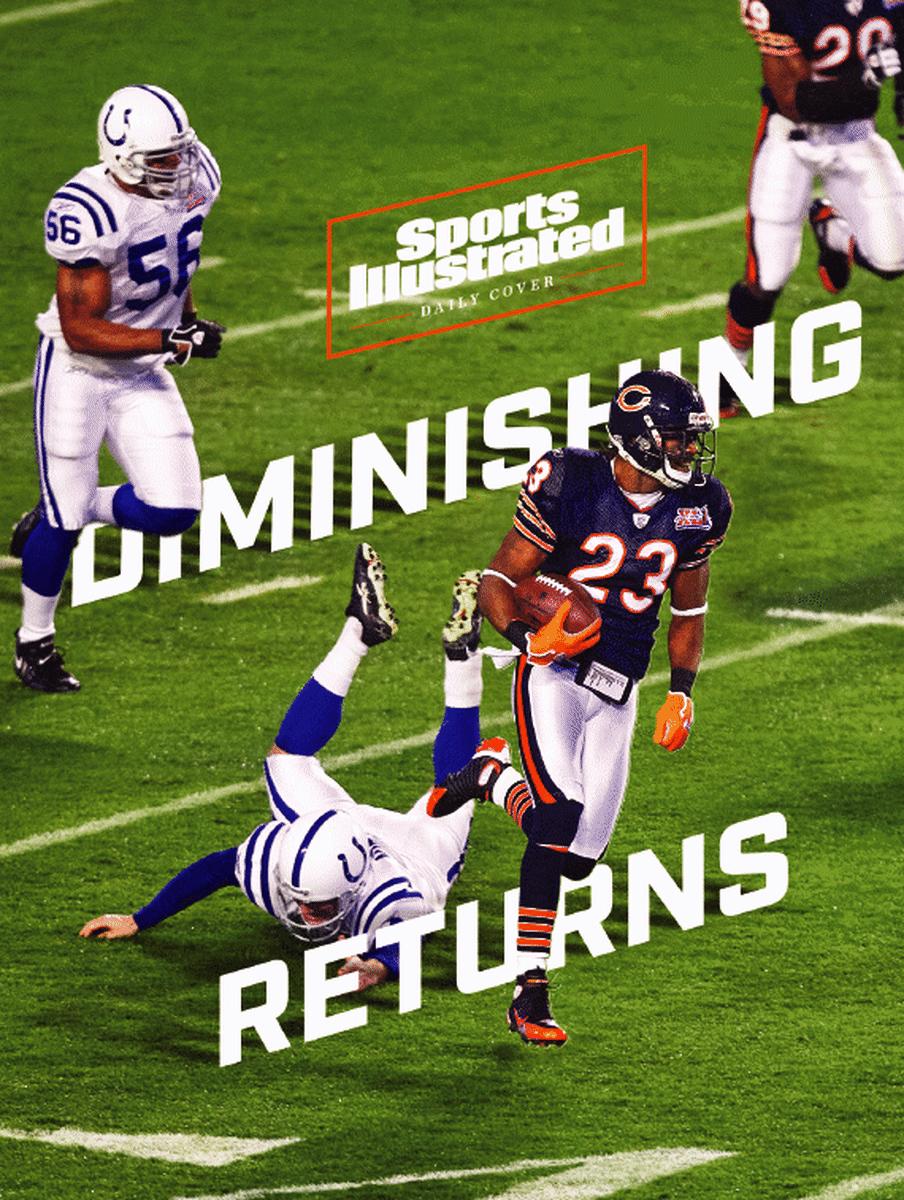

Devin Hester’s most famous kickoff return is not his favorite kickoff return.

Everyone remembers Super Bowl XLI, at the end of the 2006 season, when he took the opening kick back for a score, in the same city where he starred with the Miami Hurricanes. Ask Hester for his most beloved return, though, and he points back two months earlier, in that same season. In Week 14 the Bears were visiting the Rams on Monday Night Football. St. Louis was no longer the Greatest Show on Turf, but they still had Torry Holt (a fellow finalist on this year’s Hall ballot), who by that point had surpassed 10,000 career receiving yards.

With the game still scoreless in the second quarter, and the Rams sitting on the Bears’ 1-yard line, one of Chicago’s cornerbacks was injured and Hester, who had five interceptions as a defensive back at Miami, was the next man up. On the field, he found himself in man coverage, matched up with Holt.

“He ran a slant—the quarterback fakes like he’s gonna throw it, and he broke back out,” Hester recalls. “And [Holt] was wide open.”

Hester, for good measure, was flagged for holding. Not that it had helped. “They finally put me in on defense,” he remembers thinking, and “they come at me and get a touchdown. I was like: The only way to make up this touchdown is to run one back.”

You know what happened next. “I made it up.”

That was the first of two kick return touchdowns Hester scored that night, resetting the all-time single-season return record at six–those two kickoffs, plus three punts and a missed field goal. As a rookie. The Bears ran their record to 11–2 and clinched a first-round bye.

Lovie Smith, with the Texans, was the coach for Hester’s first seven years in Chicago. He says Hester’s presence changed the dynamic of that team, not just on the field but in the locker room.

“A lot of times, you have to convince guys to play on special teams; they just want to play offense or defense,” Smith says. “But when you have Hester back there, you don’t have to convince them. That was a badge of honor, to be selected to block for Devin.”

Hester remains appreciative of the men who helped clear his path, even if sometimes their blocking turned to gawking. “After three or four [touchdowns], we’d have guys turning around to look and see what’s going on,” Hester says. “We let them know: Hey, man, we’re gonna watch film later on, and you’re gonna see the touchdown, so keep your eyes on the man.’”

The Bears were one of the rare teams that occasionally introduced their special teams unit to the home crowd. “It was chic,” Smith says. “It was en vogue to be on the special teams in Chicago.”

Dave Toub, who back then was the Bears’ special teams coach, remembers how opponents obsessed over Hester, and how every week the only question reporters would ask was whether Chicago’s opponent would kick anywhere near the elusive return man.

“[We] had them on their heels before we even kicked off,” he says. “That fear factor gave an advantage to us.”

Such fear and speculation ran right up to the Super Bowl, when two weeks of questions were quickly put to bed as Colts coach Tony Dungy dared the Bears, and Hester found himself in Indianapolis’s end zone 14 seconds into the game.

That was his seventh return touchdown of the season. The next year he ran back six more.

In retirement, Hester’s schedule has opened up for more than just football practice. On a leather couch in a rec room at his house, he describes Daddy Donut Day.

The youngest of his three boys, 3-year-old Denali, is in day care, and Devin got a kick out of the class event, an opportunity for fathers to spend time with their kids alongside teachers and peers. They talked about what colors his son likes, what he did at recess, what he’s learning at school. “Those,” he says, “are the types of things I want to do now.”

Which is why he’s not eager to hop into broadcasting or coaching beyond his own children. He remembers what it was like when his first son, now 12-year-old Devin Jr., was born during his playing days: “I was there for him, but I wasn’t there. I wasn’t there to see his first day of school … all his class plays.”

Now, he says, “Anything that’s gonna take me away from my kids, I’m not doing it.”

Hester grew up in West Palm Beach, about 90 minutes north of Miami, but he and his wife, Zingha, have been in the Orlando area for seven years now, and in this Winter Garden home for eight months. Today, Zingha is setting up a Father’s Day feast for friends and relatives, in a room overlooking the backyard, where the kids sprint against one another and hop from the pool to the trampoline to the two-way basketball court, with a custom DH23 logo in the center circle.

Devin himself has stepped for a few private minutes into a side room, a shrine to his football career, adorned with balls from his 38 career touchdowns, on both special teams and offense, where he carved out a role as a starting receiver later in his Bears career. The space is lined with trophies, jerseys, cleats and autographed photos. In one display case, a mannequin torso wears the red blazer given to each of the 100 members of the NFL’s 100th-anniversary team, who were honored before Super Bowl LIV in Miami to commemorate the league’s centennial.

“It was very shocking,” Hester says of his inclusion on that dream team. He points out that there are “a little over 300”—354, to be exact—members in the Hall of Fame. “And then you look at the [100th-anniversary team] and … pretty much everybody on that list is in the Hall of Fame.”

Indeed, the NFL 100 team included nearly exclusively Hall of Famers, plus Hester, Peyton Manning (who has since been enshrined) and five guys who weren’t yet eligible: Tom Brady, Larry Fitzgerald, Rob Gronkowski, Shane Lechler and Adam Vinatieri. (Hester missed one name, and it hurts his argument: Billy “White Shoes” Johnson made the NFL 100 team for his punt return prowess, but he’s not in the Hall.)

“So, in this situation, it’s not us being worried about making the Hall of Fame,” Hester says, specifically naming Brady, Fitzgerald and Gronk. “It’s about whether or not we’re gonna be picked on the first ballot.”

And Hester says it absolutely matters that he gets in on the first try.

“It does. First-ballot Hall of Famers are Hall of Famers that you don’t have no question that they should be a Hall of Famer. You think about the best of the best—best quarterbacks, best running backs, best receivers. I know we don’t have any [full-time] returners in the Hall of Fame, but I did things that have never been done before.”

But don’t just take his word for it.

“There’s no man that was feared more than Devin Hester with a ball in his hands on special teams,” says Deion Sanders, a first-ballot Hall of Famer himself whose record of 19 return TDs stood until Hester came along and broke it. “And that’s coming from me.”

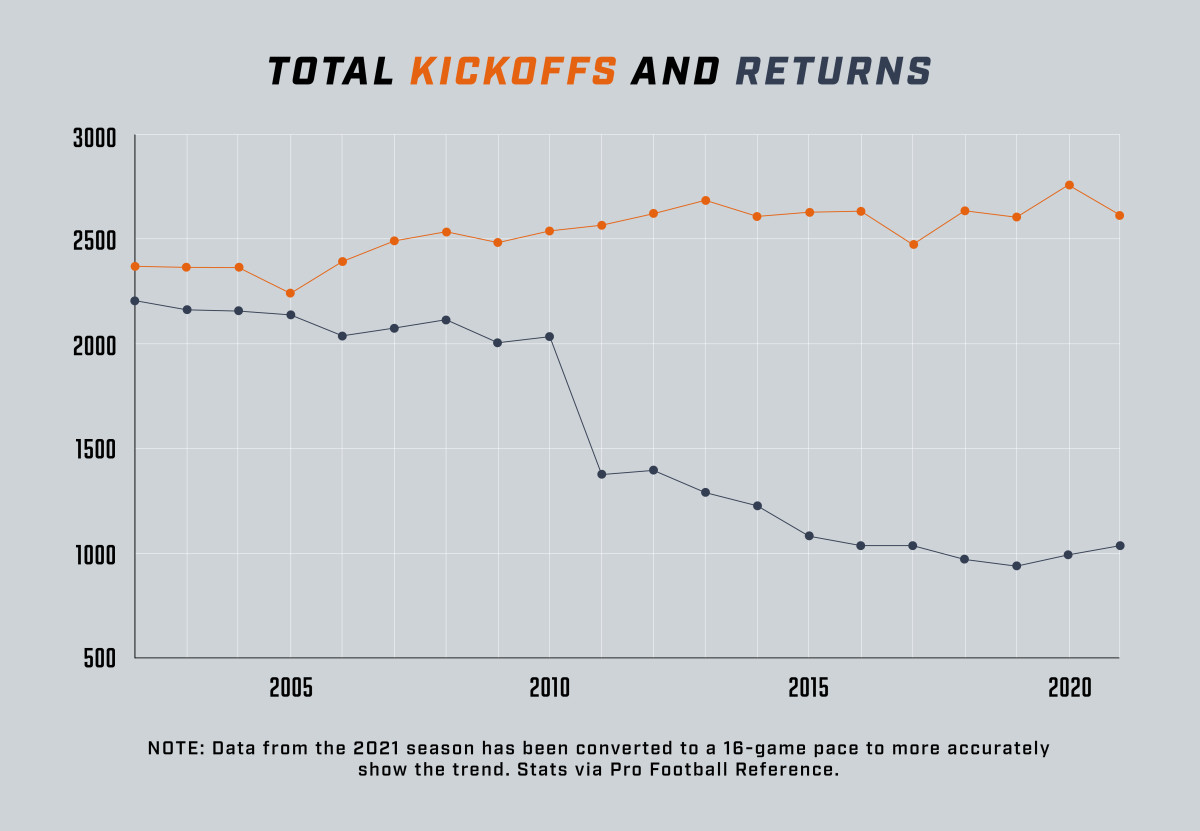

The kickoff is dying.

Teams are still booting the ball over to their opponents plenty, as we’ve seen offenses explode and scores go up. But the returns—the part of the play that made the kickoff exciting—have been rapidly squeezed out of the game.

More and more frequently, what was once among the most dramatic plays in football has been replaced by the perfunctory exercise of a kicker dumping the ball into the end zone and a referee waving his arms. A waste of real-world time that doesn’t even affect the game clock.

Anyone who has followed the NFL for long, especially since the kick was moved from the 30-yard line to the 35, before the 2011 season, is aware of this. But for those who may not realize quite how much the game has been affected, here are some telling numbers since the league expanded to 32 teams:

What this means (besides the fact that today’s fan can safely get up to grab a beer without risking missing a big play, which Toub says they stopped doing in Chicago during Hester’s day) is that the role of the return man has been significantly deemphasized. It’s harder for a player to make his living off that singular skill.

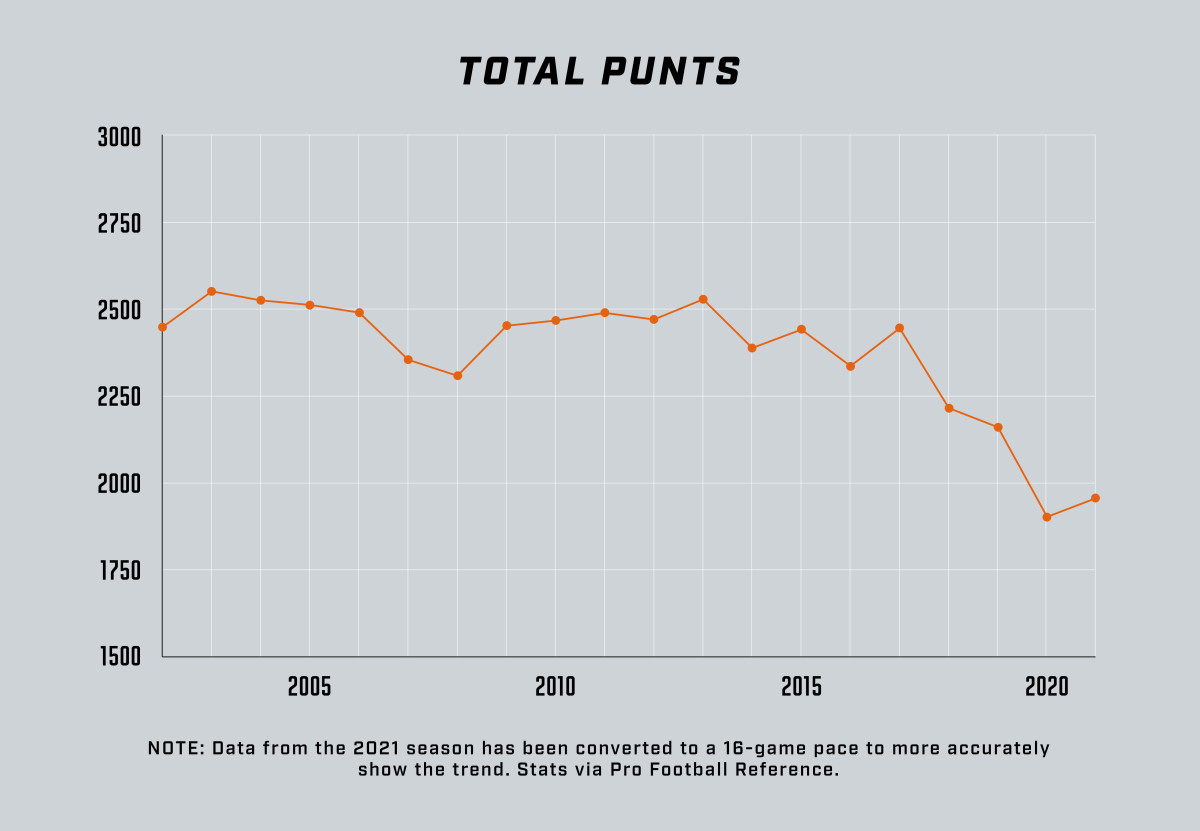

And if the kick return is headed toward extinction, then the punt should at least be considered for the endangered species list. The kickoff’s disappearance has gotten more attention because the related rule changes are so jarring, and the jump in touchbacks is such a talking point. But look what’s happened to its closest relative:

Teams are punting less than ever, for two reasons that stand out. First: Again, scoring is up. Every drive that ends in a touchdown or a field goal is one less opportunity for a Colquitt or Townsend brother to do his thing.

Second: Teams are going for it on fourth down at rates we’ve previously seen only in video games. As coaches grow more aggressive about keeping the offense out there for every fourth-and-3 at midfield—from old vets like John Harbaugh to first-timers like Brandon Staley—drives are being extended, or defenses are taking over without sending a return man back 40 yards deep.

So who’ll be the next Devin Hester? The football universe is making it harder for that player to emerge. Maybe ever.

The impetus for many of the changes in special teams rules, as most fans know by now, is player safety. The kickoff is the play most directly affected by the NFL’s attempt to protect players (on Monday the NFL’s executive VP overseeing player health and safety said that kicks and punts make up a disproportionate number of head injuries and torn ACLs) while still preserving the game that fans have fallen in love with. Toub is among those working to prevent such changes from altering the sport too much—“I don’t think you should ever take the foot out of football,” he says—and he has the platform to do it.

Since leaving Chicago after the 2012 season he’s been the Chiefs’ special teams coordinator, and he added assistant head coach to his title four seasons ago. He’s also a member of a group of NFL special teams coordinators who meet in the offseason to discuss rules and potential changes and present their suggestions to the league office.

While certain tweaks—like moving the kickoff line of scrimmage up and bringing touchbacks out to the 25—incentivized all the touchbacks that have led many to conclude that the kickoff might as well go away, the league has also implemented more subtle tweaks that may be saving the play: like legislating who can line up where, removing running starts for the kicking team and eliminating certain types of blocks.

Toub points out that every NFL team has a kicker who could launch nothing but touchbacks these days. So when you see a runback, it’s often because the opposing coach wants his opponent to run it out. And the safety tweaks may just preserve their ability to keep that strategy element in the game, along with the excitement that comes when such a decision backfires.

“We came up with a plan to make [a kickoff] more like a punt return,” Toub says. “The Braveheart-type collision, we kinda took those things away with the new rules.”

And if you look closely at the end of the kickoff graph, you’ll see that the league has seen two straight years of increase after a low of 938 in 2019. This could be statistical noise, or it could be the sign of a bounce back (even if it’s nowhere close to the pre-2011 numbers).

Can you play football without a kickoff? Sure, the NFL’s own Pro Bowl did it just this past weekend, as has been the case for the exhibition game each year since 2014. But the tail on that kickoff graph may offer hope for anyone who doesn’t want to see that play out every Sunday. Things have seemed less dire than in that crater of ’18, when many observers believed the league was truly on the verge of eliminating the kickoff, as one member of the NFL’s competition committee predicted.

And there are other reasons for optimism, including innovation outside of the NFL. For example: The short-lived XFL 2.0 debuted in February 2020 with a slew of rules that fans had never seen. The league lasted only five weeks before it shut down at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, but of the XFL’s new rules, its altered kickoff is the one that appeared to generate the most immediate and widespread praise. Each team lined up a 10-man side (with five yards separating the two) deep in the returning team’s own end, and they couldn’t move until the return man possessed the ball.

The XFL kickoff was still exciting, even if it was vastly different from watching Hester as he kept an eye on the descending ball and an army of would-be tacklers whistled in toward him. It appeared to retain a degree of suspense while also removing the costly high-speed collisions that have been commonplace for decades.

No, the NFL has yet to do anything that drastic, but options are out there. And Toub can rest easy; they won’t have to rename the sport.

But that doesn’t change the fact: There are still far fewer opportunities for another Devin Hester to walk through the door.

Hester “is the GOAT to me,” says Dante Hall, the man who himself earned the nickname “The Human Joystick” for his return prowess: six punt return TDs and six more on kickoffs between 2002 and ’07. “Obviously he has the numbers, but his vision and his ability to read blocking and make cuts—and the speed. I called it throttling: He would be in second gear, third gear, take it to fifth, back to fourth. He was made to return kicks.”

“He was magical,” says Eric Metcalf, who owned the record with 10 career punt return touchdowns until Hester came along and topped him. “He’s done something no one has ever done—[that] guys like me wish we could have done.”

Adds Sanders, who served as a mentor starting early in Hester’s career, and with whom he’s stayed in close touch: “It would be absurd if he’s not a first-ballot Hall of Famer. Hall of Famers are guys that had a direct impact on changing the game … that were, without a shadow of a doubt, real difference makers.

“This Hall of Fame thing,” he continues, “has gotten skewed a little bit, where normalcy is being applauded. That wasn’t the way it was back in the day. Normalcy is in. There’s nothing about Devin Hester that’s normal.”

Hester is not the guy you might expect if you only remember his highlights or his Deion impersonation, high-stepping his way into the end zone. He’s not loud or braggadocious. Toub calls him “soft-spoken.” Sanders says “laid-back, kinda shy.” But Hester is firm when asked about his place in history.

Do you think you’re the best returner ever? “Most definitely,” he says. “Without a doubt.”

And as he explains why, the conversation drifts away from the incredible things everyone saw him do to the incredible things we didn’t. The great mystery of Hester’s career. The part Hall of Fame voters have to look a little closer to see. What would have happened if teams weren’t so damn afraid to kick him the ball?

“You look at my stats, you see I have the most return touchdowns of all time,” Hester says. But: “Imagine if teams kicked to me my whole life, how crazy the stats would be. I really only got two or three good years of getting the ball kicked to me.”

One can look at Hester’s stats the same way that some analysts parse Barry Bonds’s numbers and wonder how many homers he might have hit if he hadn’t been intentionally walked at historic rates. Bonds, at least, gets the credit in his on-base percentage. On Hester’s Pro Football Reference page, though, he gets no black ink for the Bears’ leading the league in squib kicks or punts out of bounds.

Toub says that it got to the point where Chicago spent half its special-teams practice time preparing for evasive measures, like bloop kicks to the up backs. They sought ways to punish teams for avoiding their most dangerous weapon, and so Hester’s presence made an impact even when he didn’t touch the ball.

Hester remembers being “very frustrated with that situation”—but he knows it’s all part of his legend, the proof of his greatness. “To have teams [so afraid] to kick me the ball, where they’re trying to kick it out of the stadium? Those types of players, where coaches [fear them] and can’t sleep at night … those are the types of players that need to be in the Hall of Fame.”

Brian Mitchell, a three-time All-Pro over 14 seasons with Washington, Philadelphia and the New York Giants, has a message for any voters who don’t think special-teamers play enough snaps to warrant consideration: “It’s the Pro Football Hall of Fame,” he says, “not the Offense and Defense Hall of Fame.” And he’s happy to speak at length on the emphasis coaches famously put on “all three phases of the game.”

Toub is on the same page. And Hester’s real legacy, he says, is the way he changed special teams across the league, how teams built their rosters to stop him, and guys like him, and how it has stayed that way.

“You used to have big guys—like defensive ends and O-linemen—covering on kick returns,” he says. “You don’t see that anymore. It’s all speed guys. Your third and fourth corner; your third and fourth safety and receiver. … Now, those backup players have to be able to play special teams.”

To see Hester inducted into the Hall of Fame would feel like a win for everyone like Hester—everyone who forced that change.

“I think he should be in the Hall,” says Metcalf. “In my own selfish right, I hope he does, because then it sheds light on people like myself. People see that special teams players are really football players. People might look at me differently.”

Football will go on, with or without the kickoff. With or without another Devin Hester. But, Hester says, “You’re gonna lose another player like me. A lot of people in my heyday came to the game just to see what I was gonna do.”

Hall knows what that felt like. He equates the act of returning a kickoff for a touchdown to being a rock star. “You get to live that life for 10, 15 seconds. It’s like I’m Jay-Z or the Beatles.”

Mitchell, who now does TV and radio covering the team in D.C., knows too. No one in NFL history has returned more kickoffs (607) or gained more yards on them (14,014) than him, and his records are trending toward unbreakable, like “most hits by a pitcher” or “most 15-round decisions by a heavyweight.”

He relished his role, often getting to set the tone before the offense ever took the field. He describes his teams holding hyped-up promotions where fans could win a car if Mitchell returned the opening or post-halftime kick for a touchdown—and he says it paid out more than once.

He remembers, too, talking to another All-Pro return man of his era, Mel Gray, and saying: “Mel, we’re gonna make this a glamour position. Let’s go out there and be so good to where they gotta pay us like they pay everybody else.”

Metcalf, at least, had a role model coming up. As an NCAA-champion long jumper at Texas, he wanted to add kick returns to his long list of athletic pursuits because he’d seen his dad, Terry, do it. Terry Metcalf made three Pro Bowls as a running back and returner for the St. Louis Cardinals in the 1970s, once owning the record for most all-purpose yards in a season. Eric followed that up with three Pro Bowls of his own in the ’90s.

And while Metcalf understands the importance of making today’s game safer, he, like others, laments the way his area of expertise has been deemphasized.

“We have a guy on the football team—Devin Hester, myself, whoever—and he’s one of your best football players,” he says, “and now the rules have taken him out of the game.”

Metcalf still follows that game closely as an analyst for the Browns’ pregame and postgame shows, and he observes that even when return men get a chance these days, their intent appears different. “It doesn’t seem to me that coaches are interested in scoring touchdowns,” he says. “They’re more interested in you securing the ball. It looks like guys don’t commit to what they’re trying to do … meaning, there might be a small hole, but he didn’t try to take it. He just wants to make sure he has the ball.”

Hall chimes in: “If they were to totally phase out the return man, then it’s gonna eliminate a lot of guys’ opportunities to play. And it’s sad to see, because that’s how I made my hay” (which included landing on Late Show With David Letterman, after Hall returned touchdowns in four straight games). “I don’t think I would’ve had a chance to play in the league if it wasn’t for that.”

The Hesters will all be in L.A. on Thursday when the world finds out who will and who won’t be enshrined in August.

The whole thing, Devin says, has been “a little overwhelming. It’s a lot. The closer it gets, with narrowing the list down and the phone calls. At the same time, you embrace it, because it’s something you’ve been wanting to happen all your life.”

He has kept busy while he waits. Dray played in a U-8 league this fall against some of the best players across Florida, and again Devin coached. Dad proudly reports that son won the league’s version of the Heisman, that their team won the league’s Super Bowl, and that Dray was the MVP of the big game. Devin Jr., meanwhile, is getting ready for track season and Denali will soon start T-ball and soccer. Devin will be at games and practices, but he’ll leave the coaching in those sports to other parents.

Hester keeps up with the NFL; he stocked his two fantasy teams this year with a mix of young guys and veterans he once played against. He says he briefly drifted away from the league after he retired, but experiencing the game with Dray has brought him back.

He likes the trend of coaches being more aggressive on fourth downs, even if it’s keeping punt returners off the field. And he says he dreams a bit about how he might be used today, with all the creativity around the league.

“Offensive coordinators are finding a solution to put the ball in the best players’ hands,” he says, pointing to players like Tyreek Hill, Jaylen Waddle and Cordarrelle Patterson.

Hester finished his own career with 255 catches for 3,311 yards. Perhaps puzzling by today’s standards, and his obvious skills, he accumulated only 116 career rushing yards, never carrying the ball more than seven times in a season. Things would probably be different now, as looping end-arounds have largely been replaced by streamlined jet sweeps.

“I felt like it wasn’t taken advantage of, the caliber of player I was,” he admits. “I could have easily [made] a bigger impact in today’s game.”

Now, in retirement, he relies on his Peloton to keep in shape. It’s one of those cruel ironies of football: Because of the same broken sesamoid (big toe) bone in his right foot that ended his playing career, the man who once raced against a cheetah at Busch Gardens in Tampa can no longer run. Doesn’t matter. Distance running, he says, was “not my cup of tea” anyway.

He has also found time to give back within the larger football world. Twice this season he addressed players at Jackson State, where Sanders won FCS Coach of the Year and revitalized HBCU recruiting. Sanders has been Hester’s mentor, dating back to when the former was still playing in the NFL and the latter was at Miami, talking to the press about following Sanders’s path. They grew close enough that when Hester broke Sanders’s record, in 2014, Sanders, who was sitting at the game’s on-field NFL Network postgame set, shed tears of happiness.

Sanders now looks at his protégé and observes: “Success isn’t success without a successor.” It’s clear that he is talking about more than just football stats.

Who will succeed Hester? In the most literal sense, he’s focused on his own kids—“I don’t wanna do anything where I’m away from my babies,” he reiterates—plus the players he coaches, and others, like Sanders’s team, to whom he can offer life lessons.

In the NFL, maybe the next Devin Hester—a player who shines on special teams enough to warrant consideration for Canton—will also have to shut down star receivers at the goal line or run between the tackles. Maybe it’ll be a now 9-year-old whom everyone already jokes about playing at The U someday.

Or maybe Hester was one of one: the right combination of vision, instincts and speed; a kid who wanted it badly and worked hard to get there but also was fortunate to reach the stage just before the curtain fell forever.

• Al Michaels, on the Eve of What Might Be His Last Game

• It Hasn’t Been Easy for Joe Burrow; Just Ask His Parents

• Cooper Kupp’s Scientific Approach to Greatness

• Arts and Crafts, Belichick-Style: On “Padding,” the Job From Hell