Josh McDaniels Explains All the Lessons He’s Learned

It’s 11 a.m. local time on the third Monday in May, and new Raiders coach Josh McDaniels is pointing to his left—over a shelf full of photos with family, Lombardi Trophies, and old coworkers like Robert Kraft and Tom Brady in them—and out the window of his corner office into the parking lot, with the Spring Mountains in the backdrop.

“One of the easy things that we’ve tried to keep in mind is we’ll get the best out of everyone here if they love coming to work every day because they love who they’re working for,” said McDaniels, sitting behind his desk. “That sounds so ridiculously simple. Seriously. But it’s the truth. If the players enjoy being coached by us the way we’re coaching them, if the coaches enjoy being treated the way they’re being treated, if the scouts and the personnel department enjoy the way that [GM] Dave [Ziegler] runs the meetings and gives everybody a voice, then when they drive in here in the morning? You should see this.”

The gated blacktop lot, adjacent to a set of three practice fields, is filled with cars, a long jump shot away from a desk full of binders and orderly stacks of paper.

“You drive in here at 6 a.m.? I’m not s---ting you when I tell you more than half these cars are already here,” McDaniels continued. “If I come in at 6, I’m like the 75th person in the building. If I come in at 5, I’m probably the 15th person. And that’s what I’m saying. We wanted that to be the case.”

The 46-year-old isn’t patting himself on the back, and he’s not doing that for Ziegler, who left a job leading New England’s personnel department to come with him, either.

Instead, on this spring afternoon, he’s trying to bring to life the vision he and Ziegler have set out, to reinvigorate one of the NFL’s most iconic brands after a year of nonstop tumult inside the franchise. And once you dig into it, you’ll see that what McDaniels is doing in pointing to that lot is actually the opposite of chest-thumping. Because this vision of his, and theirs, is really a result of being humbled, being reflective and trying to be better.

At the end of the desk, with his back to all those cars, is Ziegler—the Raiders’ 44-year-old GM who was brought into the NFL by McDaniels 12 years ago, who’s known McDaniels since he was a college recruit and has known of McDaniels for even longer.

The temptation for so many has been to brand the Raiders’ beautiful, still relatively new facility as Patriots West, since McDaniels and Ziegler got here and quickly imported a slew of lieutenants and ex–New England players. The truth, though, is that’s not what this is, and it’s apparent from the minute you step into the building. It’s not the Patriot Way, either. It’s, in their words, “Our Way,” and by “our,” they’re referencing way more than two people.

“I think Our Way is the foundation of everything being built on relationships, and being inclusive and being open-minded,” Ziegler said. “And at the same time still being convicted on the things we believe in.”

“But also giving people an opportunity,” McDaniels added. “Bill [Belichick] gave us the opportunity to be ourselves, and to be independent thinkers and to have our own opinion, and he didn’t micromanage that. And that’s one of the best things that I’ve paid attention to the last decade of my life, watching him do it and then feeling like, That’s how you have to do it. … Our Way is Let’s try to do it the best way, and it might not be what we know.”

It took a long time for McDaniels to get here—it’s been more than 11 years since he was fired by the Broncos, and more than four years since he stepped away from the Colts’ job to stay in New England. But now that he’s arrived, he’s bringing all that he’s learned with him. And, fair warning, it looks significantly different than you might expect.

Las Vegas’s new assistant GM, Champ Kelly, chose to be where he is now, in an office wedged between Ziegler and holdover exec DuJuan Daniels (himself a former Patriot scout), and it might sound funny that he did so, at least in part, because of the experience of working with McDaniels in Denver in 2009 and ’10.

But it’s the truth in why when Ziegler came calling, and Kelly considered his options, the decision to reunite with a guy he saw fired a decade ago was easy.

“First of all, out of respect to the football mind, it’s rare,” said Kelly, smiling broadly. “But the person, I didn’t feel like everybody got a chance to know and uncover who the person was. … Not that he wasn’t himself before, but maybe not as many people got the chance to see that.”

There was a very specific reason for that.

McDaniels was 32 when he got to Denver. And the workload he foisted upon himself when he arrived was maybe the biggest way in which he showed his naivete. He had trouble getting the assistants he wanted out of their contracts with other teams. He committed—once Broncos owner Pat Bowlen fired the Goodman father-and-son tandem (Jim and Jeff) that had run Denver’s personnel department—to installing the Patriots’ scouting system with first-year GM Brian Xanders. He didn’t hire an offensive coordinator.

He worked and worked and worked.

“It was me and Xanders together trying to implement the scouting system—the only one I knew, that was it—and prepare for a draft, and put in an offensive system, and teach them how I wanted to coach the quarterback, and help the defense do certain things, and it was just so many things,” McDaniels said. “It was impossible. It was so cumbersome to try to attack everything and be a part of everything; it was impossible to be good at any of it. And that’s my fault. It wasn’t anybody else’s fault.”

Worse, for McDaniels, is what he let slip, which is where it swings back to what Kelly was saying. The reason few got to really know McDaniels in Denver was largely because by spreading himself too thin, he’d made himself scarce to much of the team.

He’d dictate what he wanted from up high, and the message would filter down through others to save him time. And that meant if there was bad news to be given, there might not be a relationship built on the front end to soften the blow, nor would McDaniels always be delivering that bad news on the back end. Instead, he’d be grinding away on the draft board, or third down prep or anything else he chose not to delegate.

Perception has long held that McDaniels’s failures in Denver came because people thought he was trying to be someone else (namely Belichick). What may be closer to the truth is that too many people in the building didn’t know who McDaniels was at all, and eventually that became a big problem.

“I didn’t understand the significance and the value that goes with everybody in the building feeling credibly satisfied with how they’re being valued by the organization,” McDaniels continued. “I didn’t have a great perspective on it. I knew I was valued in New England to a degree. But I don’t think I was aware of somebody needing to say to the video guys, Hey, you guys did a great job with that. Or the equipment guys, or the trainers, I just wasn’t doing that in New England [from 2001 to ’08]. I didn’t have to do it.

“And I think once I got pulled in too many directions, where I wasn’t capable of handling all that, [relationships] suffered because of it. And I’d say now, if I was gonna choose between two things, I would choose the other stuff. The relationship part of it, I would say, would be more important to me than some meeting with X’s and O’s.”

Ziegler got to Denver in May 2010 as a scouting assistant. Kelly, Xanders and current Raiders director of scout development Keith Kidd, interviewed, then hired him on McDaniels’s recommendation. And since the two were on opposite ends of the spectrum, they didn’t interact much.

But Ziegler saw enough to see what his friend was doing to himself.

“We didn’t interact a ton, because he was going in a million different directions,” Ziegler said. “You could tell there was a lot more pressure on him than the guy I was around before. And comparing where he’s at now to then? He’s so much more relaxed, I’d say. … It’s night-and-day in terms of just his day-to-day personality.”

He had a decade to confront reality. How the Raiders are being built shows he’s doing just that.

The first time Ziegler saw McDaniels with his own eyes was in the fall of 1994. The former was a junior receiver at Tallmadge High, a mid-sized suburban school near Akron not known for its football. The latter was the son of a legendary coach and senior quarterback at powerhouse Canton McKinley. McKinley played the 100th installment of its rivalry with neighboring Massillon that November, and the rematch was set for the playoffs two weeks later.

“Massillon had a quarterback that went to Akron,” Ziegler said. “Willie …”

“Spencer,” McDaniels cut in.

“Willie Spencer,” Ziegler said. “And I’m a sports fanatic, so I still remember there was that article with you and Willie.”

“Akron Beacon Journal,” McDaniels said.

Ziegler then described the cover of that day’s paper—with the two QBs mean-mugging each other—and told the story of how, with his season over, he went to see McDaniels and McKinley at the Akron Rubber Bowl that Friday night. So for Ziegler, it was pretty exciting the next fall when he went on a recruiting visit to John Carroll, and was hosted by a particular Carroll freshman. “When I first met him, I thought that was cool,” Ziegler said. “He played in the Big 33 game. No one from Tallmadge had even played Division I football.”

Ziegler enrolled at Carroll in 1996, and the two became what McDaniels refers to as “linemates” in the receiver rotation, with their future New England coworker (and now Texans GM) Nick Caserio at quarterback. “They’d send us in there; it was like the two hoodlums,” McDaniels said. “The guys that were gonna get underneath the guy’s facemask and have the officials breaking us up when we’re blocking.” They bonded over that similarity and also some differences.

One contrast was in how Ziegler played, with a borderline-reckless aggressiveness that showed in his game as a return man. “He wasn’t going to fair catch,” McDaniels said. “He was right, though, because he was really good at it.” Another difference came with how, as housemates during McDaniels’s senior and Ziegler’s junior year, Ziegler was away a lot, doing his studying at the library, while McDaniels would do it at the house.

“So when it comes to all the roles he’s had, it’s the same thing,” McDaniels said. “And that’s been one of the best things about him forever; he’s not gonna worry about trying to tell you what he thinks you want him to say. And in our profession, especially when you’re a young guy and you’re trying to come up, it’s, Man, what does Josh want me to say? Or, What does Bill want me to say? And that’s not Dave. Dave is, I’ll do the work, I’ll have my own educated opinion and that’s what I’ll believe in; and I’m gonna tell you the truth.”

That dynamic between the two of them became the template for how they’d fill out their staffs in Vegas. And it sustained their relationship over time, even if they weren’t talking all that regularly, with each having his own group of college friends, and a smaller crew (that included Caserio) connecting them.

So when McDaniels went to cut his teeth under legends-to-be Nick Saban at Michigan State in 1999 and Belichick in New England in 2001, Ziegler took the scenic route. After college, he landed a job as a ninth-grade social studies teacher and freshman football coach at Kenston High in Bainbridge, Ohio. He went to Arizona to coach and teach. He wanted to see whether he could take it to the next level after that, sending letters out to 30 colleges looking for a graduate assistant spot. Only John Carroll responded. So he got a counseling master’s there.

Then, he was a limited-earnings coach at Division I-AA Iona (making $7,000/year), before returning to Arizona to work as a guidance counselor and coach at prep power Chaparral, which is where McDaniels found him in 2010. As it turned out, all that experience would pay off in time, as Ziegler took his shot at scouting—first in Denver, where he was held over by John Elway, then in coming to Foxborough, on the good word of both Caserio and McDaniels.

Neither had any hesitation in advancing Ziegler’s name to Belichick in 2014.

“I probably would have done that no matter what I was doing,” McDaniels said. “Like if I was in sales, and he happened to be a salesman, I would’ve called. … It’s almost like this unwritten rule [with JCU football alums]—if we stick our neck out for you, you’re not letting us down.”

Ziegler wouldn’t. In Foxborough, he rose from pro scout, to pro director, to a role Belichick created for him, assistant director of player personnel, to replacing Caserio last year as the team’s new director of player personnel.

Again, what McDaniels and Ziegler were looking for as they built their staff in Vegas mirrored what they saw in each other—football smarts, mental agility, emotional intelligence and the ability to bring differences to the table and challenge each other.

In a very natural way, they were able to inject the sort of alignment into the Raiders that McDaniels couldn’t get with the Broncos: with three offensive assistants coming from New England with him; ex-Patriots assistant Pat Graham leaving a job as Giants defensive coordinator to take the same job in Vegas; and former Patriots assistant Jerry Schuplinski, who had left New England but stayed in Belichick’s tree with the Giants and Dolphins, joining as senior offensive assistant. Likewise, Kelly jumped at the chance to reunite with Ziegler on the scouting side, and Patriots national scout Brandon Yeargan jumped aboard as Ziegler’s new college scouting director after the draft.

That so many wanted to come was indicative of the rep both Ziegler and McDaniels carried.

For Graham, coaching in the AFC West—and the challenge of defending Patrick Mahomes, Russell Wilson and Justin Herbert—was a draw, as was the fact that the program in Vegas would, naturally, be familiar, with familiar values and principles. But it was McDaniels himself, too.

“One, he’s really smart. Two, he works hard. And there’s an extreme attention to detail,” Graham said. “[When] I was working on the opposite side of the ball in New England, you could see that. When you see him from afar, when I was at Green Bay and had to play against him, when I was at Miami and had to play against him, you could see that. … I would argue he’s the best play-caller in the league.”

And similarly, for Mick Lombardi, his personal relationship with McDaniels, and connection to the program were factors.

“My respect for him as a football person, it probably can’t get any higher,” the Raiders’ offensive coordinator said. “Him as a play-caller and him as a game-planner, it’s in my opinion at an elite level. And it’s something that I’ve been able to grow from. I’ve grown more over the last three, four years with him, as one of his position coaches, than I did my other seven years in the NFL. … So when he had this opportunity, and then presented me with an opportunity, it was, This is a no-brainer.”

But for every Lombardi or Graham or Kelly, or Carmen Bricillo, Jerry Schuplinski, Rob Ryan or Bo Hardegree, there was an Edgar Bennett or Cam Clemmons, holdovers from the previous Raiders staff. Or a Tom Delaney running contracts, or Chris Cortez running the training room, or Bobby Romanski running equipment—all Raiders employees going back decades. Or a Jon Gruden hire such as strength coach A.J. Neibel.

And that was where McDaniels and Ziegler wanted to strike a balance, bringing in enough people they trusted to delegate to already, while engendering trust by giving everyone in the building a shot to stay with the team after the new guys were ushered in.

This, they say, was never going to be a down-to-the-studs rebuild.

“If we had an opportunity to do something like this, whether it was together or separate, we were gonna go in there with the understanding—always assume the best of people, always assume that you’re talking to a really genuine, good human being that has a role and a job in this organization,” McDaniels said. “And let’s figure out what’s the best thing for the team and the organization going forward. But let’s give everyone the benefit of the doubt.

“And when you go in with that mindset, it’s a different feeling for them, and it’s a different feeling for you, because you’re not saying, Let’s go scorched earth, and get rid of this person and that person. We don’t need to do that. There were a ton of good people here.”

“We recognized there were some talented players on the team, too,” Ziegler added. “They had a core group of players that were good players. … So I came in with the mindset, too, I think we both did, Let’s see who these people are, let’s see what they know, let’s see what they’re about and let’s also take it as an opportunity to learn from them. There are some processes they have in place that I want to learn about—are they better than the processes I have?

“And in some cases, there are some things where it’s like, Yeah, I want to do that.”

On another level, it meant rewarding those people for what they’d done before.

McDaniels barely finished shaking hands with his new boss, owner Mark Davis, to accept the job in January before sitting down with Ziegler and a list of players to call. One by one, each guy would get to hear from his coach and GM. Maxx Crosby and Hunter Renfrow were on that ledger. Denzel Perryman, too. But there was never a doubt who’d get the first call.

“If that’s the guy you’re gonna try to win with at that position,” McDaniels says, “then that person deserves to hear from you right away.”

Truth be told, Derek Carr was already excited about playing for McDaniels from a football standpoint, just off eight years of institutional, inside-the-league knowledge of his offense, and what he’s capable of bringing out in a quarterback. But he didn’t have any idea what to expect from a personal standpoint. And while he knew the story of McDaniels and Jay Cutler from Denver, he planned to go into the new relationship open-minded.

That first phone call was just the first way in which McDaniels would exceed expectations.

“I’ve been through so many coaching changes. I’ve been through so many GM changes. And you know with every change, they may want to do things a new way,” Carr said. “And for them to make their first call me, one, it showed me who they are. They told me that they were committed to me. And the cool thing, too, is, in public, they’ve been committed to me. Usually when you get a new coach, GM, they kind of slow-play it like, Oh, we’ll see …

“I’ve been through that. My future is always up in the air, it seems like. But these guys just made it clear, No, we believe in you, and you’re our guy, and we believe we can win with you. And we’re going to prove that to you, too. We’re gonna sign you to an extension.”

They got into specifics in what they liked about him, too—his arm talent, his maturity, his competitiveness—and followed through on their word with a three-year, $121.5 million extension. And while not everyone made that sort of bank, those who remained, such as Crosby (and he got a four-year, $95 million extension), from the old staff were given the same sort of respect as the new brass seeded relationships.

The calls were especially impactful in light of what the guys had been through—two team president firings (one after McDaniels arrived), a midseason coach resignation amid controversy, a GM firing and the in-season imprisonment of a teammate, Henry Ruggs III, who was charged with DUI resulting in death after a fiery crash that killed a 23-year-old woman and her dog last November.

Crosby got his call five minutes after seeing the news on Twitter. He was with his agent, who said, “I bet you Coach calls right away.” Minutes later, the phone rang. It was McDaniels. And Crosby had a good idea, then and there, that good things would follow.

“We won 10 games in the National Football League. That’s not easy,” Crosby said. “We had a lot of distractions, a lot of things going on, and we still found a way to win. So there was no need to rebuild. It was just more about revamping what we already have. … And obviously they wanted to show their commitment to not only myself but DC. They want everybody on the same page. There’s no secrets. They’re very up-front and very honest about everything. And, for me, that’s all I want.”

Turns out, he got that, he got the money and he got more. In fact, as his deal was getting done in March, Crosby was solicited for information on free agents by Ziegler, and he was among the first to know when guys were added. He was in Ryan’s office, asking for Chandler Jones cutups (wanting to study technique), when McDaniels popped his head in to tell Crosby that Jones (another former Patriot) was about to become his teammate.

In a real way, in that moment, Crosby felt the skin he had in the game. And because the team was invested in him, it now goes the other way, too.

“[Maxx] Crosby’s contract extension, [Derek] Carr’s contract extension, for me?” McDaniels said. “Those were big deals, because you’re rewarding someone who’s earned it. And, yeah, they haven’t played for us yet. But we’ve already built up a trust and a relationship with the people. To me, it was everything we’re talking about.”

Those things are now prioritized, which is showing up in all sorts of ways. Here’s another: As McDaniels spoke from behind that desk, Carr was battling a cold, and soon thereafter the coach more or less forced the quarterback to go home, knowing that the illness was going around Carr’s family.

“Usually, football coaches are like, Do everything, and then if you can’t do it, whatever, we’ll figure it out,” Carr said. “He’s like, No, I care about you as a person, and I want to make sure you’re O.K., and the football part, I’m not worried about. You’ve proven you’ll take care of that. He has definitely shown the personal side, to the 100th degree, to me.”

A week later, McDaniels and Ziegler would work out free agent Colin Kaepernick, part of Ziegler’s commitment to pulling every lever in personnel. That might be awkward for some starting quarterbacks. For Carr, because the relationship was there, it wasn’t an issue.

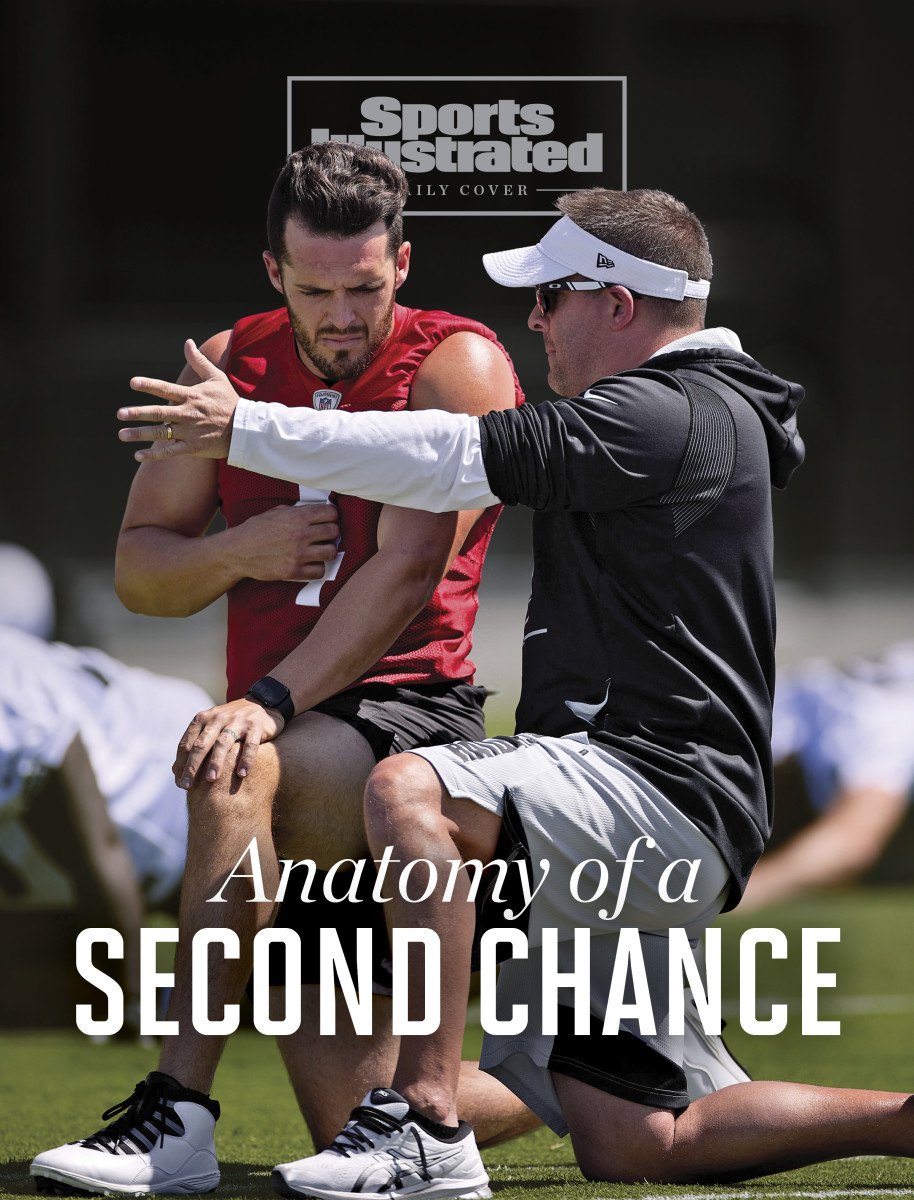

On this Monday morning, McDaniels asks for a few minutes before we get started—Renfrow, whom guys here joke leads the building in questions, has one he needs answered, and new quarterback Jarrett Stidham (another ex-Patriot) wants a couple of minutes of his coach’s time.

Neither needs to wait long to get his attention.

“One of the things I remember about my experience in Denver, there was always such a deadline for the next thing that I had to be a part of,” McDaniels said. “And right now, I’m going on many less deadlines. Like, right now, Hunter had a question, and then Stidham had something he needed for me. O.K., I’m here. I’m not in a meeting, I’m not up on the third floor where someone can’t find me, I’m not in the offensive staff room. There’s none of that. …

“In New England [the second time around], I had one role. I wasn’t spread too thin. So did I have a great relationship with the video guys? Hundred percent. The people in the equipment room, do I love those guys? Absolutely. One-hundred percent. Did I just text [Patriot PR chiefs] Stacey [James] and Aaron [Salkin] the other day because they won the Pete Rozelle Award? Yeah, because I have a great relationship with those people.”

There are dozens of other examples of McDaniels practicing what he’s preaching on the importance of those relationships. Once Matt Feeney was brought aboard as defensive quality control coach before the combine to complete the staff, McDaniels brought the group to the rooftop of The M Resort, the team’s hotel, for dinner. Ziegler did the same for his scouts on a balcony at The M during Super Bowl week.

McDaniels has, on his desk, index cards with players’ birthdays (Clelin Ferrell’s card was atop it when I was there, with his birthday coming the next day), to remind him to write each guy a note when the day comes. That was an idea he actually got from Ziegler, who last year sent Patriots scouts handwritten letters before Christmas, personalized to tell each guy how and why he valued them.

And with so many coaches’ and scouts’ families still back in places such as New England, New York or Chicago, finishing out the school year while the days in Vegas have been long, McDaniels has worked to make up for what they’re losing. Schuplinski’s family was in for Easter week and, when they pulled up to the building, McDaniels hurried to the lobby to meet them (“He must’ve seen them from his office,” Schuplinski said) and led them on a tour of the building himself.

Graham mentioned how McDaniels has given them some Fridays off, with plenty of notice to plan travel, and half days on Thursdays so they could get back home. And Lombardi had a story similar to Schuplinski’s from April—he’d asked McDaniels whether he could go pick up his wife at the airport since she was landing in the middle of the workday.

“He was like, Absolutely, are you bringing them here?” Lombardi said. “I was like, Yeah, if it’s O.K. And he was like, You bring them to my office first; I want to say hello. Stuff like that goes a long way.”

McDaniels himself brought up the story of his chief of staff, Tom Jones, wanting to go see his son play in a Little League championship game during the team’s rookie minicamp.

“Those are little things,” he said. “But if he didn’t feel comfortable enough with me, he wouldn’t have come and asked. He’d have said, Honey, I can’t be there; it’s rookie minicamp, there’s no way. I’m not asking. And they won the championship. That’s cool. I don’t want him to feel like you can’t ask me that, because I’m gonna tell you, 100 out of 100, go. Go.”

And these stories go back to what the Raiders are trying to build.

“That’s the thing,” Ziegler said. “The general vibe being in the building, there not being eggshells. … You can have the standard high, you can still give critical feedback, you can still hold people accountable, you can still do all those things, but have a vibe where people can be themselves, and people feel appreciated.”

The results, just four months in, have been noticeable.

“It’s unbelievable,” Davis added. “There’s a lot of good energy. They brought good people in. But they also gave the people that worked there an opportunity to keep their jobs, to earn their job, and a lot of them did. He gave everybody a chance, and that gave everyone a good feeling.”

The idea is that cuddly, warm part of all this will allow people to be tough on one another, to hold each other accountable.

“I’d say for me that’s from being a guidance counselor, being a teacher, those experiences,” Ziegler said. “The relationship was really what you had to solidify first to make any progress, whether you’re a classroom teacher or a guidance counselor, and you’re trying to help someone through a problem.”

“They won’t trust you if you don’t,” McDaniels said.

“As a guidance counselor, you have to create it on the front end so if there is a problem down the road, you’ve already created the relationship, so you can help someone that’s having a mental health issue, or going through something else,” Ziegler continued. “The relationship has to come first.”

May’s rookie minicamp, for the coaches, allowed for proof of concept on that.

Day 1, to be frank, wasn’t great. McDaniels was tough on the players. He was tough on the coaches. Some guys were out of shape. Other things weren’t smooth. He let his staff hear it and gave the coaches a list of things to work through, that he thought just needed to be better. On the next day, Saturday, they were. And that’s where Sunday morning’s staff meeting began.

“He said, It was obvious that the stuff I said was poor; you guys put in the time, the effort, to challenge the players. I challenged you guys, and some of the stuff improved in a short period of time,” Graham said. “And he said, That’s a reflection on you guys, and he said thank you. He said, That’s what we’re looking for. And to me, he doesn’t have to say that. We all know that’s our job. But he’s reinforcing and taking the time to start the meeting off on Sunday saying that, that he recognizes it and he acknowledged it.”

More than just that, he empowered the coaches to make a difference, and Ziegler’s done the same with scouts, which has two benefits.

The first is the trust and faith that it generates.

After the draft ended, Ziegler put Kelly in command to captain the effort to sign college free agents, with Daniels, Shaun Herock and Andy Dengler also in leading roles. And before that, in the fifth round, there was a deadlock in the war room that led Ziegler and McDaniels to pull some coaches into a discussion, to break a tie on the pick of Tennessee DL Matt Butler.

“We liked Butler, too,” McDaniels said. “I’m just saying it was kind of close here, so we went down and said, Hey, give us your two cents on this again. Boom, boom, boom, Butler, done.”

On the coaching side, McDaniels will often give his coordinators the reins to change things. And while it might happen more naturally on defense, since McDaniels is still the offensive play-caller, and Graham an experienced coordinator, it happens on offense, too.

“His willingness to change things and do something different, let me do things like script practice or run certain drills I wanna run out there—that makes me feel valued,” Lombardi said. “I don’t feel like, Oh, man, I’m just a slavedriver doing what he wants. That’s not the case. Jerry and I are making the red zone tape for tomorrow. He trusts us to do it. We’re gonna do it, and we’re gonna present it to the offense tomorrow. That’s something where we feel like we’re part of something, big-time.”

Which is where the second benefit, for McDaniels, comes.

“You compare [Denver] with now, I know what my role is,” he said. “So I can be the head coach. I will be the play-caller, but I don’t have to be the general manager, I don’t have to be the director of pro personnel, I don’t have to be the quarterback coach, I don’t have to be the offensive coordinator, I don’t have to be the special teams coach.

“That lesson that I learned, and it was the biggest one I learned, is the one thing I’d say we’re doing the best job of right now. No question. I’m not pulled 100 different directions. And, again, in Denver, it wasn’t anybody’s fault but mine.”

It’s also why, in so many ways, this situation feels right.

As McDaniels is quick to point out, he and Ziegler could’ve gone separate ways. While structure and staffing were part of why McDaniels stepped away from Indy in 2018 (and he and Colts GM Chris Ballard are on good terms now, for the record), that was never about control. It hasn’t been for either guy—McDaniels and Ziegler came close to getting jobs separately, in Philadelphia and Denver, last year.

“We never had some big, scripted-out plan,” McDaniels said. “We were just two guys trying to continue to grow and aiming for something that might be out there for either one of us in the future individually. And if it happened to be together, it happened together. But I don’t think we were ever like, Hey, let’s hook arms. Because obviously in Philly, it wouldn’t have been Dave [as GM]. And Dave interviewed in Denver, and that wouldn’t have been me [as coach].”

But now that this is how it worked out, the two appreciate how it came together.

The one hang-up? The coach jokes that his friends said they never thought it’d be with the Raiders. And as he says that, he swivels his screen to show the black-and-silver helmet.

“My friends were the opposite,” Ziegler says, getting a laugh from McDaniels. “You’re totally a Raider! That’s him. That’s him.”

Schuplinski has known McDaniels for 27 years—the two arrived together in Carroll’s 1995 recruiting class. McDaniels recommended him to Belichick in ’13, the two worked together for six years there and now are together again in Vegas. And just as he knows how much McDaniels has grown since Denver, he’s actually seen as much growth more recently.

“His patience has really, really improved from when I was with him before,” Schuplinski said. “I know, we all know, he looked back on his notes from the last time he had an opportunity to be a head coach. He’s told all of us these stories—here’s where I screwed up. I can see him making a real concerted effort from the moment I spoke with him about coming here to when I walked in the building through everything else; his patience has been unbelievable.

“Now that doesn’t mean he’s like, Yeah, do whatever you want. But his patience has been awesome.”

McDaniels and Ziegler also know there are bigger tests ahead.

But there’s belief here, that when the first losing streak happens, or when the first rash of injuries hits, the trust being built now will carry over. And that McDaniels is now just as likely to be with the defense as the offense on the practice field, or just as sure to help a player work out a personal issue as he is to drill him on his hand placement, or that Ziegler and McDaniels and their staffs take time to sit and eat lunch with players, or that they pop into people’s offices, is no small part of it.

In fact, as they see it, it may be the biggest piece of the whole thing. They plan to set a high bar for everyone. They know it’ll take investment on both ends to clear it.

“You can make it as complicated as you want it to be,” McDaniels said. “But the simplistic version of it, Dave and I would probably say about the same thing—there’s a championship way to do everything. We don’t have to have a meeting to describe that. It just is what it is. If you’re a scout, your report should be freaking detailed and on point. And if you’re a player, you should bust your ass in that period and do everything that you can to do the technique the way we’re asking you to do it.

“If you’re a coach, you should make sure you’re well prepared and that your message is simple and that players can understand what you’re saying and your communication is the way it should be. … If it’s the equipment room, guys’ stuff is in their locker in the morning when they come in. And you don’t have to micromanage that if you just say, Listen, we want to try to do things at a championship level. And to me we’re not just going to win a championship if 10 people are performing at that level. It really has to be everybody.”

Ziegler then looks at his old college teammate and adds, “And then when you see the things that are not there, you identify them.” And that, McDaniels points out, can come from anyone going to anyone else. That’s where, he says, everyone has skin in the game, and it truly becomes Our Way.

“The way we’re trying to do it is our way,” McDaniels continued. “It’s not kumbaya, but it’s also no eggshells. They know we love them. So when you pull them aside and correct them, it’s being received the way you want it to be received.”

“Because my group,” Ziegler said, “they know I’m gonna challenge them, too.”

“Everybody does,” McDaniels said. “We’re gonna challenge them. That’s how you win.”

And based on the look of that full parking lot, everyone here is ready to take on that challenge.

More Daily Covers:

• When Henry Ruggs III Drove 127 mph Into a Carr, One Man Ran Into the Fire

• 100 Bold Predictions for the 2022 NFL Season

• How the Eagles Built Flexibility and Cashed in on Draft Night

• Behind the Spectacle of Colin Kaepernick’s Comeback Tour