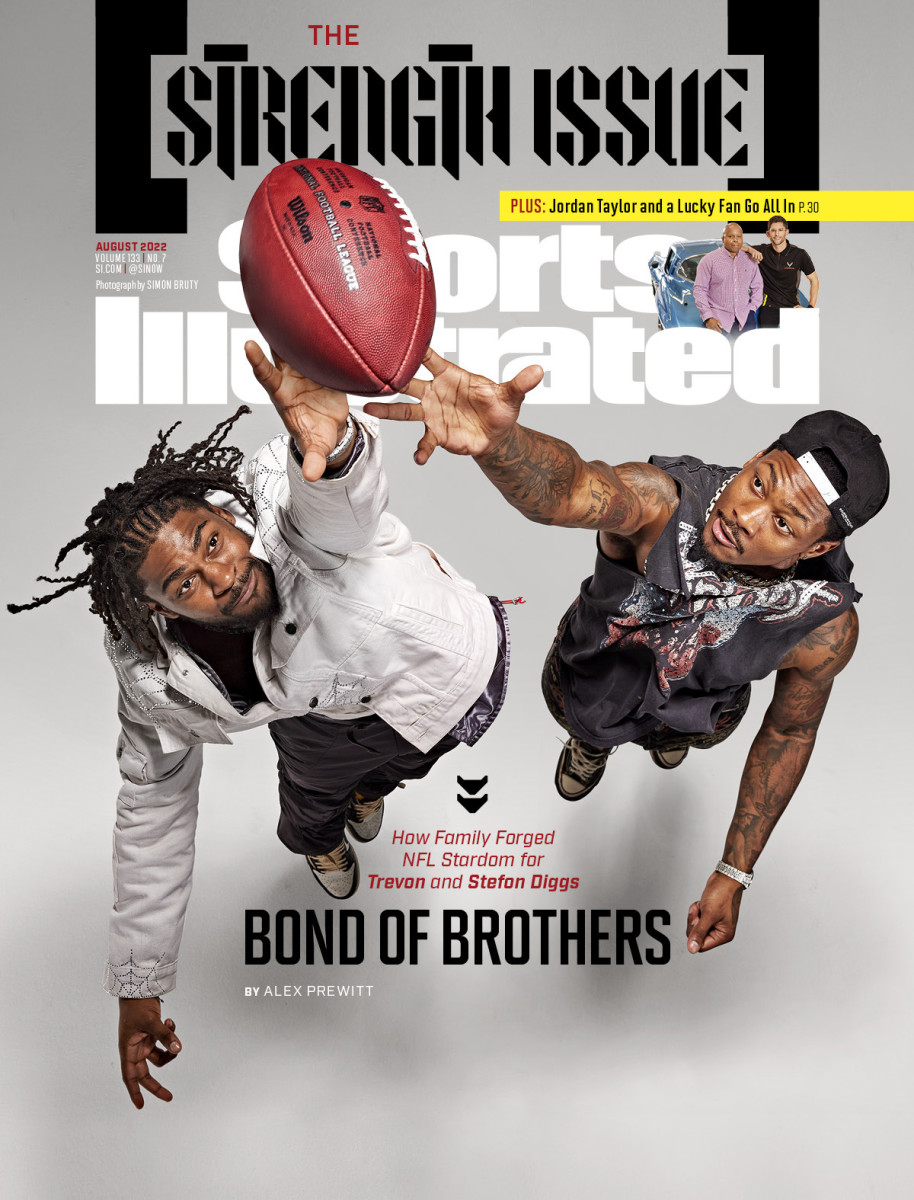

Stefon and Trevon Diggs: How the Brothers’ Unbreakable Bond Was Forged

Strength comes in many forms and has many sources. But what does it mean to be strong? We have a few ideas. Check back throughout the week for more.

Stefon Diggs is cruising behind the wheel of his robin’s-egg-blue Lamborghini Urus in early May, a month after the star Bills receiver signed a contract extension that guarantees him $70 million over the next six seasons. Riding shotgun in the luxury SUV is Cowboys cornerback Trevon Diggs, whose own big payday will surely follow soon thanks to a breakout 2021 campaign in which he bagged more interceptions (11) than any NFL player in 40 years. As is often the case whenever these brothers get together—and get on a roll—it’s best to sit back and let their rapport take center stage.

STEFON: Lemme tell you the truth. [Gestures toward Trevon.] He don’t think nobody that good. Even people that I think is good! That’s a true DB.

TREVON: Some people are cool. [But] I don’t think nobody is like, “Yo, he’s a problem. He’s amazing. I can’t do nothing with him.”

STEFON: I ain’t never heard bro on some scared, goofy s--- like that.

TREVON: If you go into a game already thinking, “All right, Stefon, he’s super nice, he can do this, he can do that—”

STEFON: That’s what coaches do, bro.

TREVON: Coaches really trying to scare people. We be at meetings and stuff. And they be like, “All right now, this piece right here, he fast, he can catch, stay on him.” I be like, ‘Pssh, he aight . . .”

STEFON: That’s why I always say, he went against a dog before he saw any other dog. I was a dog way before that.

Elite sibling tandems are hardly rare in football, from the Mannings to the Watts to the pair of pairs (Jason and Travis Kelce, and Joey and Nick Bosa) who made the 2022 Pro Bowl alongside the Diggses in February. Yet never before have two existed on opposite sides of the game’s one matchup—out on the island, mano a mano, receiver vs. cornerback—that perfectly encapsulates the essence of the sibling rivalry. Thanks to their age difference, Stefon, 28, and Trevon, 23, have neither played on the same team nor ever lined up against each other in a real game. But their snarling training battles, waged as pups in the greater Washington, D.C., area, form the bedrock of all they have since built as individuals, with Stefon leading the league in yards (1,535) and catches (127) in 2020 before snaring a career-high 10 touchdowns last year, the same season in which Trevon tied an NFL record with seven interceptions in the first six games. “I think he’s the best receiver; he thinks I’m the best DB,” Trevon says. “So when we compete, we’re going against the best, and that happens to be my brother.”

Countless examples make up a large part of the family lore. Their older sister, Porsche, recalls one “really chill” family reunion abruptly ending when someone broke out a football and Trevon, then a high schooler, picked off a pass while guarding Stefon, then starring at Maryland: “Everyone goes crazy, and Stefon is like, ‘Run it back! That’ll never happen again!’ After that, the cookout was just over.” A nearly identical scene unfolded about a year later, in April 2015, at the reception after their maternal grandfather’s memorial service. “They were still wearing their funeral clothes, just talking trash and competing,” their mother, Stephanie, says. “I had to break it up after an hour when it got dark.”

Over time, though, the tough love of their youth has grown into a more tender, joyful bond, best exemplified by the small, sporadic, spontaneous moments during a 12-hour day of otherwise staged activities for a Sports Illustrated shoot. Like when the 6' 2" Trevon, taking a breather from a series of one-on-one basketball games, wraps the 6' 0" Stefon around the waist and gently hoists him up, Dirty Dancing style, to fix a stuck net.

And later, at a favorite Jamaican lunch spot in College Park, near Maryland’s campus, beneath fumes wafting from a meat smoker the size of a nuclear warhead, as the alpha dog silently extends a paw across the table and flicks a tiny booger from the tip of his little brother’s nose.

Digging into a spread of jerk chicken, braised oxtail and beef patties, the brothers turn their attention to the beginning. Asked how far back their dog-eat-dog streak stretches, Stefon replies, “We’ve been working that since day zero, for real, for real.”

Stefon was almost 5 when Trevon arrived. “I was excited as f---,” Stefon says. (The brothers are the two children of Stephanie and husband Aron Diggs, but the fourth and fifth in the family overall, including Aron’s sons Aron Jr. and Mar’Sean and Stephanie’s daughter, Porsche). And while Stefon didn’t embrace every element of the older-brother experience from the jump—Stephanie recalls his first and only attempt at changing baby Trevon resulting in a backward diaper—he clearly relished having a tagalong opponent at every turn, whether in Madden, pickup basketball or full-contact knee football inside the house. “I used to hit-stick his ass,” Stefon says.

STEFON: We competed at everything. But when I think about the competition I have with other people, I don't care about them. I want to win by any means.

TREVON: I'm competing with somebody else, and say they break their leg—it’s different. If I’m competing with [Stefon and] he breaks his leg, I might give him my leg, know what I’m saying?

STEFON: I want to win. He wants to win. But it was never, ever coming from a bad place.

In fact, this intensity was simply trickling down from both sides of the genetic tree. (Years later, in another famous family tale, Stephanie, a longtime Amtrak employee, would corner Ozzie Newsome aboard a Northeast corridor train and rip into the Ravens executive for failing to draft Stefon: “They should fire your ass!”) But their father took the reins from a football standpoint after each boy enrolled at age 5, quizzing Trevon on formations while watching their beloved Cowboys on television on Sundays and requiring Stefon to complete three tasks before bedtime each night: homework, prayers, and 200 pushups and situps. “My husband really pushed them to have a good work ethic,” Stephanie says.

Then, in January 2008, following a half decade of health problems that had boomeranged him in and out of clinical care, Aron Sr. died of congestive heart failure at a Fairfax (Va.) hospital, still on the waiting list for a heart transplant. He was 39. Stefon was 14. Trevon was 9.

“That s--- was f-----d up,” Stefon remembers. “We was hurt. We was sad. Because he was not only like a dad, he was like a cool friend, the type to teach you a lot.”

Some of their father’s most important lessons proved impossible to pass on before the end. After the funeral Stefon often heard people tell him that he was the new man of the house, so one day Stephanie returned from an overnight shift with Amtrak to find Trevon on the couch when he should’ve been in class. “He was like, ‘Eh, Stefon said I didn’t have to go to school,’ ” she says. But soon enough—thanks to some stern lecturing from Mom about his liberty-taking—Stefon transformed “into being more of a father figure and setting good examples,” Stephanie says.

Nowhere was this more evident than on the football field, as Stefon sought to both carry on Aron’s belief that the boys were destined for NFL greatness and demand the same tireless work ethic his father taught him: Where Aron used to take the boys to run bleachers and suicides at local parks after school, soon Stefon was dragging Trevon to daily workouts. And when Trevon later expressed a passing desire to attend a specialized arts high school, Stephanie remembers Stefon swiftly shooting down the idea by insisting, “Tre can paint all he wants after he plays football and gets his money!”

The same protective instinct is why Stefon chose the hometown Terrapins in February 2012, over a raft of offers from more prestigious programs (including Ohio State and Auburn). That fall, Trevon began as a freshman at Wootton High School (Rockville, Md.), earning a two-way starting role on the football team. “Whenever Stefon was there at games, the level of focus and intensity in Trevon would heighten,” says Tyree Spinner, then Trevon’s coach. Other times it took only the mention of Stefon’s name to keep Trevon from getting sidetracked in team meetings. “All I had to do was say, ‘Hey, I’m about to call big bro,’ and there was an instant snapback,” Spinner says.

Looking back, Stefon says he never would have chosen Maryland as an only child: “I still regret that, just from a developmental [standpoint].” But while his three seasons in College Park were pockmarked by teamwide tumult (four quarterbacks threw to him as a freshman) and personal injuries (a broken right leg in 2013, a lacerated kidney in ’14), he left having succeeded in one crucial component of his broader mission: to keep watch over Trevon while letting him glimpse what it takes to fly solo.

TREVON: I used to be at Maryland every day, every weekend.

STEFON: In college.

TREVON: In college. I’m [actually] in high school, ninth grade, I’m going to UMD.

STEFON: Basically.

TREVON: And I feel like that probably kept me out of trouble, being right there with him. He’s looking after me, he’s got his teammates making sure I’m straight. … I got to see a lot of stuff that a lot of people my age didn’t get to see. And I never made no bad decisions, no bad choices. I just watched him. Just watching and learning.

STEFON: That sneak peek real.

Read More From SI’s Strength Issue

After appearing at wideout, safety and returner during his true-freshman season in 2016 at Alabama, helping the Tide capture the SEC crown before losing to Clemson in the national title game, Trevon was informed by Nick Saban that he would be converting full-time to cornerback. Though the intent was to give Trevon more reps than he’d get as part of a stacked receivers room—headlined by future first-round picks Calvin Ridley, Jerry Jeudy and DeVonta Smith—he was soon on the phone with Stefon, sobbing.

“I’m in Alabama . . . out there by myself,” Trevon says. “I got nobody to call who could relate. Except him.”

By then Stefon was no stranger to unexpected obstacles. He had tumbled to the fifth round of the 2015 draft, sitting through two nights of draft parties at home without hearing his name; when the call finally came from Vikings brass, Stefon was wrapping up a workout with Trevon at Maryland’s stadium, having grown tired of waiting around. (The 19th wideout taken, Stefon has since amassed more yards, catches and touchdowns than anyone in the class.) And then, after a strong rookie preseason, he didn’t even dress for a game through Minnesota’s first three games.

STEFON: Sitting on that pine—oh my god, I had wood in my ass, boy.

TREVON: He had sweatsuits.

STEFON: What was I eating?

TREVON: Had a sweatsuit, eating sunflower seeds. I know my brother. I know how good he is. I see who’s out there. I know none of these dudes are better than him. And it just hurt to see him inactive every week.

STEFON: Sunflower seeds and Gatorade.

TREVON: [But] he never looked back soon as he got that chance.

Sure enough, when injuries to two receivers cracked the door for his Week 4 debut, Stefon broke out. After a Week 5 bye, he had consecutive 100-yard games in Weeks 6 and 7, the first Vikings rookie to do so since Randy Moss in 1998. And so, listening to his tearful brother a thousand miles away, Stefon could empathize with how Trevon felt. “Low-key, we’re used to being the man wherever we are, whatever level we play at,” Stefon says. He also knew the tough love that was needed. As Trevon recalls, “He’s like, ‘Man, I’m not trying to hear all that crying s---. Get to work.’ ”

Swallowing his disappointment, Trevon poured himself into the new role, arriving early and staying late, studying YouTube videos of Tyrann Mathieu, Patrick Peterson and other star DBs. Another hard lesson (and another weepy call to Stefon) followed when Trevon, after earning a starting job as a sophomore in 2017, lost it halfway through a subpar season opener against Florida State to a fifth-year senior, Levi Wallace. “I just really, really wasn’t ready,” Trevon says.

But he stayed true to his brother’s advice, overcoming a broken foot as a junior to record three interceptions, eight pass breakups and two defensive scores as a third-team All-American in 2019. In doing so he even flipped the script on their usual relationship, setting the example for a change. “As he weathered those storms, that gave me a lot of motivation,” Stefon says.

Indeed it wasn’t long before Stefon found himself sailing into another surprise squall—one that he characterizes as a “dark place.” By that point he had become a Vikings legend with the Minneapolis Miracle catch to beat the Saints in a Jan. 2018 divisional playoff. (Among those who witnessed the 61-yard, walkoff touchdown live was Trevon, attending his first-ever NFL game.) And he had followed up a five-year extension in the summer of 2018 by joining Adam Thielen as the team’s first pair of 1,000-yard receivers since Moss and Cris Carter. But then, just a season later, the Vikings’ offense shifted to a run-heavy scheme. His targets plummeted, and several unexcused absences led to a $200,000 fine and a trade request. “The dark place was understanding where I was and who I was and what I wanted from myself and it not happening,” Stefon says. “Digging myself out of that place [of] not feeling like enough, and trying to hone in on the problem, [I realized] I just needed a change of scenery,” Stefon says.

Change arrived in March 2020, around the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the Bills swapped four picks, including a first-rounder, for a No. 1 receiver to pair with quarterback Josh Allen. (“I’ve got no problem with Minnesota,” Stefon says. “Still got a lot of love and respect in my heart.”) It was a moment of intense joy, relief and culmination all bundled together, same as the one that awaited the Diggses less than two months later.

Tension hung in the air at Stephanie’s D.C.-area home as the second round of the 2020 draft lurched on, an evening heavy with the memory of how far Stefon had slipped five years earlier. While Trevon remained typically stolid, Stefon alternated between offering pep talks and dissing the teams that dared pass up little bro. “You could see it in Stefon, like, ‘These dumbasses don’t know what they’re doing,’ ” Spinner says. Finally, at No. 51, commissioner Roger Goodell announced Trevon’s selection to the Cowboys; sitting on a couch, the cornerback leaned over and nuzzled up to Stefon, who wrapped Trevon in a brotherly headlock.

Despite the wait, the destination felt serendipitous for several reasons. “I thought it could be a blessing in disguise,” Stefon says. “He could’ve been playing for the Jaguars if he went in the first.” Mainly, though, it was because both boys had grown up big Cowboys fans, an allegiance inherited from their late father. Aron Sr. had encouraged their football careers with an all-work, no-frills mindset, but the older brother took a beat that day to share the immense fulfillment he felt watching Trevon take flight.

As Stefon recalls, “Especially considering everything that we’ve been through individually, not just together, I wanted him to remember that, like, ‘I’m proud of you. You came a long way. I used to wash and wipe your ass. I love you.’ ”

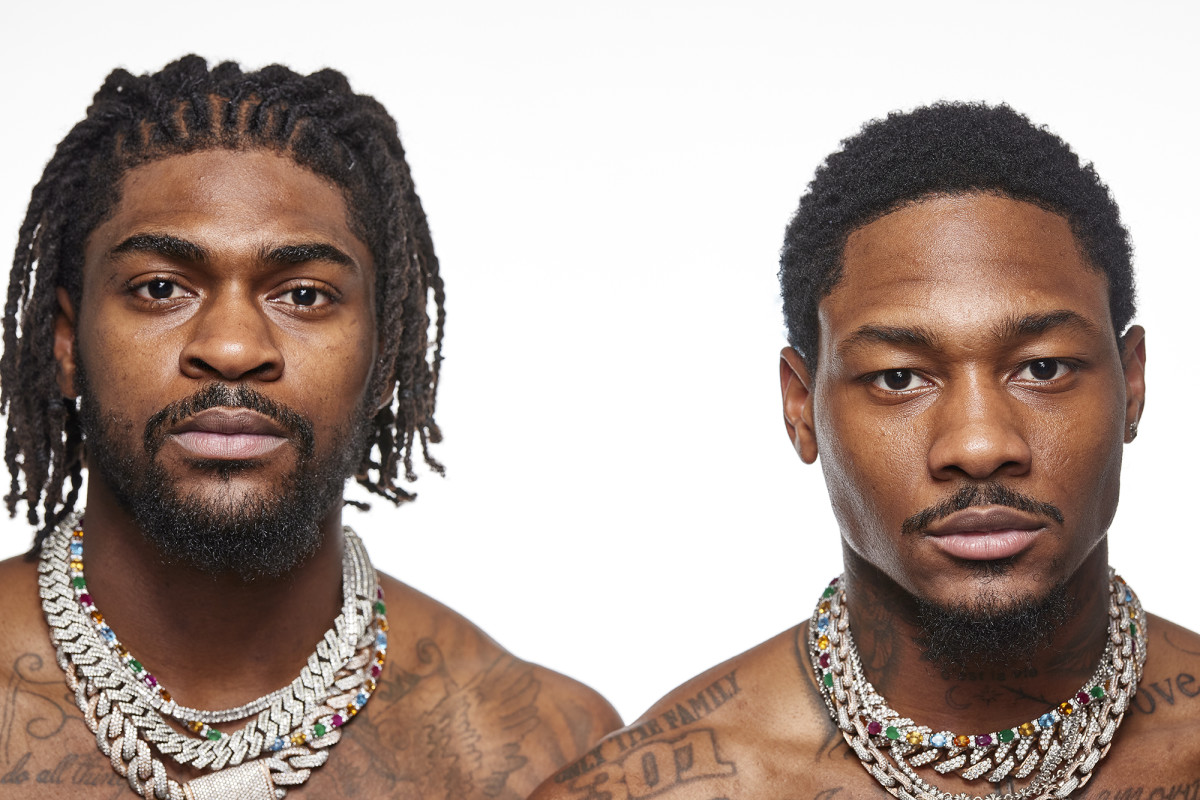

Spend time around Stefon and Trevon, and several truths crystallize. First, as with many close siblings, they talk in their own language. (For instance, in the Diggs Family Dictionary, commonly employed synonyms for interceptions include “pickles,” “picnics,” “pickin’ cheese” and “books,” as in to read an opponent’s route like a book.) Second, it is Stefon who does most of the talking. “Tre is quiet but sneaky,” says Mike Locksley, Stefon’s offensive coordinator at Maryland and later a member of Alabama’s coaching staff during three of Trevon’s four years there. “Stef is the obnoxious, loud one.”

Just ask Wallace, the former Alabama defensive back who later, as Stefon’s teammate for two seasons in Buffalo, found himself having to answer for taking Trevon’s starting job. “When I first saw [Wallace], I was like, ‘How could they put you in front of my bro?’ I never let that go.” Or ask the fellow Bills who caught an earful from Stefon over dinner one Sunday last October, the night before a road game against the Titans in Week 6, at the same time Trevon and the Cowboys were facing the Patriots on prime-time television. “The whole game, my teammates be beefing with me because I’ve been talking so much s---, that my brother [is] the nicest DB in the league,” Stefon recalls.

The hype train continued chugging as the Buffalo contingent returned to their Nashville hotel, where a lobby TV was showing the fourth quarter of what was then a one-point game. “I walk in and say, ‘If he ain’t got a book by now, it’s coming,’ ” Stefon says. Sure enough, moments later, New England rookie quarterback Mac Jones sailed a pass wide of receiver Kendrick Bourne, and Trevon hauled it in and ran it back 42 yards for a critical touchdown in an eventual 35–29 Dallas win. “I’m popping hella champagne,” Stefon says. “Like, ‘I told y’all he was gonna get his hands on it.’ ”

Family relations aside, Stefon is only slightly more generous than Trevon when it comes to praising opponents—such is the confidence born from a lifetime of competition against one of the best in the world at the opposite position. “I told Tre this a while ago: ‘Bro, 70% of [NFL] receivers are gonna be easy to check,” Stefon says. “There’s only like seven to eight spicy receivers who can catch, can create separation, can run fast, can stop. . . .’ ” The elder Diggs is even stingier about those covering him, listing just three NFL corners as “the only ones that really follow” No. 1 wideouts on a game-by-game basis: Xavien Howard, Marshon Lattimore and Trevon.

STEFON: I can go play corner. I swear I can.

TREVON: He probably could.

STEFON: That s--- is not hard. Cause there’s hella people doing a bad job. Trust me, I know. [Gestures toward Trevon.] But that's why I think he's so nice, because he played receiver. I know he could play receiver in the league.

In the brothers’ hive mind, it is man-to-man or meh. “If you only playing zone, you ain’t that good to me,” Stefon says. “And you could be amazing at zone. But it's hard to play man for four quarters.” To them the appeal rests in the primal clash for space, and for the ball—the same one that has shaped them since childhood. “Like you and me on the street, being in that box together,” Stefon says.

They still work out together every offseason and follow most sessions by hitting the basketball court for bragging rights. “A spitting contest, they’re still gonna battle to win,” says Stefon’s agent, Adisa Bakari. “[Not long ago] they were both talking about picking up golf clubs and debating who would be better.” But they have little need to run routes against each other with such intense purpose anymore. “We don’t got to do that all the time to get better,” Trevon says. Adds Stefon, “It’s different. Back when we was together all the time, all I did was work out, all day every day, so we spent more time doing one-on-one stuff. We was just trying to hit it. Got to be a little more smarter.”

Instead they have what Stefon calls “more tailored” discussions about their craft; like when, early in Trevon’s rookie season, he called Stefon for advice after learning that he would be shadowing Cardinals receiver DeAndre Hopkins in his first full-game one-on-one matchup. Stefon’s reply: “I said, ‘Tre, if I could tell you anything, bump and run his ass. . . . D-Hop is a possession receiver. He can slide, too, don’t get me wrong. He can run. But he ain’t no blazer.” The results: Trevon held Hopkins to just two catches for 73 yards (with 60 of those coming on a fourth-quarter drag route in which Trevon ran into a pick).

The lessons are no longer limited to football, either. Asked what mistake he made as a young pro that he wants Trevon to learn from, Stefon answers before the question is even finished: “Not having a Florida residency straight out the gate [for the no state income tax]. Lost millions of dollars.” At one point during the SI shoot, Stefon hangs up from a call with a jeweler friend and immediately begins counseling Trevon on the benefits of cultivating relationships with dealers. As Stefon explains, their relationship has evolved to be “more protective in different ways—not so much physical, more so decision-making, keeping his head on straight. He plays for America’s team. That’s a big deal.”

They enjoy spending what they have earned on themselves. Stefon describes going through the process of selling his downtown D.C. loft and hunting for a bigger house in the suburbs, requiring somewhere to store his “hella clothes, hella cars.” And when the brothers arrive for the photo shoot each brings a suitcase full of designer outfits that he handpicked himself, plus a shared lockbox of sparkling watches, chains, bands and other accessories, including matching ruby necklaces that Stefon bought after signing his second contract with the Vikings and a pair of gemmed pendants in the shape of shovels. But there is a deeper reason why the elder Diggs’s curriculum includes economics now, too.

“Making sure you put some money up, that’s all I really care about, because that’s the only way you’ll be able to take care of your family,” Stefon says. “Luckily, we got two people that can do it.”

The boy spies the Lamborghini Urus and flies off the sidewalk, like a moth to a $200,000 candle. No older than 10, he cuts across a right-hand lane of idling traffic at a red light in Northwest Washington, approaching the passenger’s side and all but poking his nose inside the open front window. “Hey! Hey!” he calls out. “What you guys do for—”

A pause. An epiphany. A bug-eyed shriek: “BRUH! That’s Stefon Diggs!”

Behind the wheel, Stefon chuckles and offers a gentle admonishment: “What’s up, shorty? You better not be walking up to people’s cars. You didn’t even know who was in here!” Then he pulls out a wad of cash, peels off a pair of $100 bills and hands them over. “Take your ass home,” Stefon tells the boy, who has now been joined in the middle of New York Avenue by two similarly aged friends. “And share some with them.” The light turns green. Other drivers honk. The kids clamber back to the curb. The SUV speeds down the block.

And Trevon sits silently shotgun, totally unrecognized.

No matter what the rest of their careers hold, a little brother may always be just that to some. But where Trevon grew up hearing jeers of “YOU’RE! NOT! STE-FON!” from opposing high school fans, he has clearly burst out from Stefon’s shadow thanks to a historic season that inspired Michael Irvin to describe Trevon as “Deion Sanders-like,” and for Primetime himself to publicly endorse Trevon’s candidacy for NFL defensive player of the year. (Trevon finished fifth.) “The way I hear about him, people don’t even really want to talk to me,” Stefon says. “They be like, ‘You know I’m a Cowboys fan.’”

But the brothers are never far apart these days, in part because each has a kid, both age 5, who is exactly like their uncle. “When I look at her, I’m like, ‘Whoa, you act just like Tre,’ ” Stefon says of his soft-spoken daughter, Nova, who needed a decent bit of coaxing from dad before mustering the courage to tell Bills GM Brandon Beane—after Stefon signed his massive extension in April—“Show me the money!” Her cousin, Aaiden, meanwhile, is a chip off Stefon’s chatty block. Stephanie tells a story about a birthday party that Trevon threw last fall, at which the boy marched up to Ezekiel Elliott and exclaimed to the rugged Cowboys running back, “Zeke, you don’t run very hard! You don’t hit the holes very hard!”

Plus the brothers are rarely far in a literal sense, either; whether training, traveling or hanging out at one of Stefon’s three condos that he owns outside Buffalo, they agree that they are together “nine times out of 10” every offseason. (Rare recent exceptions, Stefon says, include when Trevon passed on joining his more adventurous brother for skydiving in Los Angeles, bungee jumping in Japan, and sewing and pottery classes.)

STEFON: Us being away from each other for long periods of time and not talking? It ain’t never happened. No way. Tre, what's the longest we went without talking?

TREVON: I don't know. That don't even sound right.

One thing that they used to talk a lot about was what it would be like to play on the same team, something they have never done at any level due to their five-year age gap. For Stefon that “dream” faded in April when he signed his extension as part of an offseason gold rush for receivers. “I was like, yeah, that’s out of reach now,” Stefon says. “Maybe in the next lifetime or something. I want to finish with the Bills, and I’m pretty sure he’s not going anywhere anytime soon.” (Trevon’s response? “Who knows? I feel like it could happen eventually.”)

With the Bills and Cowboys scheduled to meet in 2023, the brothers will soon settle another hot topic: Who will prevail in the NFL’s first brother-vs.-brother, WR1-vs.-DB1 showdown. (A much-ballyhooed role reversal during the 2022 Pro Bowl, with Stefon defending Trevon and the former’s ex-Vikings teammate Kirk Cousins airmailing them both, doesn’t count.) The consensus among family and friends: Break out the flags, but also the tissues. “Stefon will be doing a lot of trash talking, because he wants to prove that Tre could never beat him,” Stephanie says. “But I think he’ll also get emotional. Like, ‘After all the hard work, after everything I put into him, my little brother is here in the league, too.’”

Trevon, for his part, needles Stefon; he is waiting to cash in all of his little-sibling karma—built up over two-plus decades of L’s in video games and sports—for one big victory over big bro. “He said if there’s gonna be a day he beats me, it’s gonna be in the Super Bowl,” Stefon says in the car, before turning to talk straight to Trevon. “I’d be hurt. You’d hold that over my head forever. No Madden, no basketball, it don’t matter. You beat me for that confetti? I might not even talk to you for a couple years.”

More likely a day or two, at most. After all, no victory is thicker than blood—nor capable of breaking a bond that can be measured in a single, flicked booger.

Watch the NFL live with fuboTV: Start a 7-day trial today!

Read More Daily Covers:

• Who’s Still Got Milk?

• The Reinvention of the World’s Heaviest Sumo Wrestler

• ‘Oh, You Look Like the Rock’: Finding Rocky’s Family

• Kelly Slater Won the Super Bowl of Surfing at 50. So, What’s Next?