Joe Burrow and the New Normal

Swaths of moss topped with large ferns spread against a wall of brush, boulders and some kind of metallic panel full of tiger stripes. The director of this landscape is militaristic in his timing, calling out a two-number cadence before a hiss signals the unleashing of flames shooting out of metal canisters behind the leaves.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHHHHH.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHH.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHHHHH.

The sights and sounds taken together create the illusion that this rainforest is about to explode.

Here's how you can get Sports Illustrated's Football Preview today!

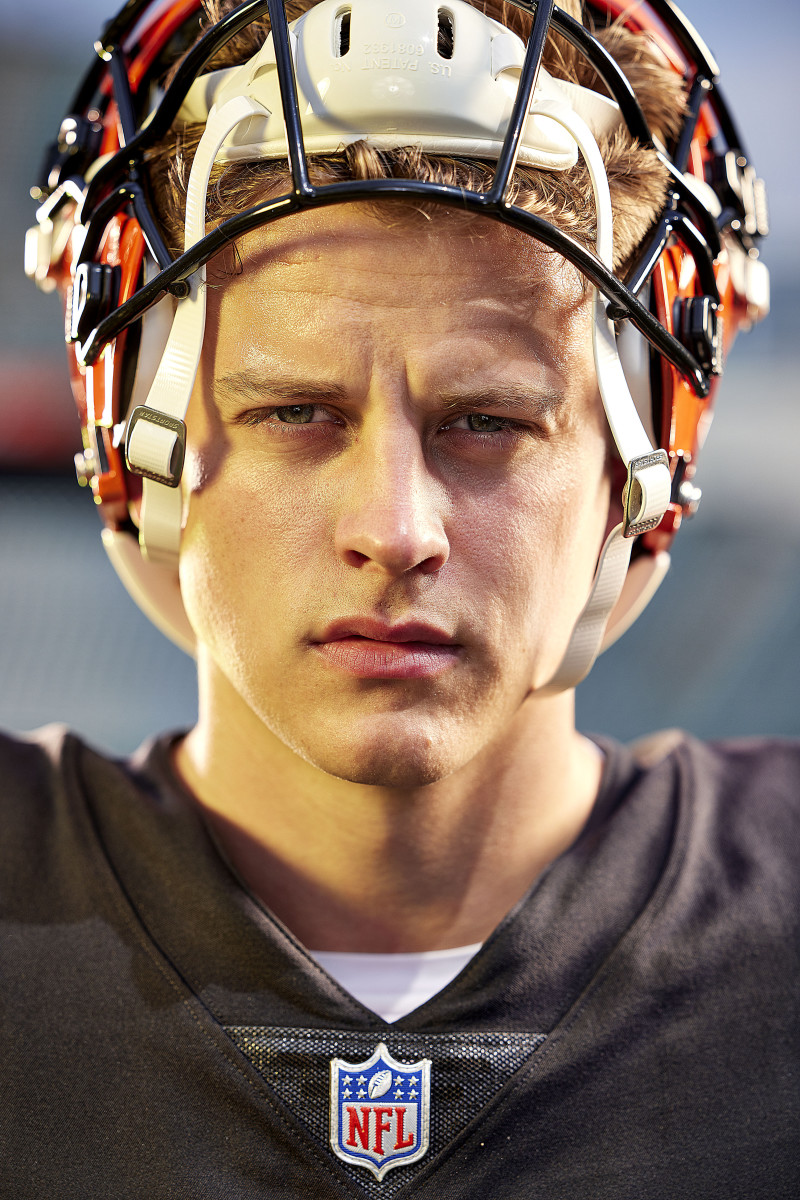

It is Joe Burrow’s third photo shoot of a sun-soaked June day in southwestern Ohio; this one is for the team, the resulting shots to be splashed across the Paul Brown Stadium jumbotron this fall. Over the course of those sessions, he has been asked to pantomime throwing a football, to stand with his hands holding his collar, to crouch in pre-snap formation and to spin the football on his fingers, which—like everything else—seems to come effortlessly to the man who last season led the Bengals to one of the most stunning Super Bowl appearances in modern NFL history. Still, when the ball flutters off his hands and onto the turf, two members of the Bengals’ equipment staff parked nearby laugh in a loud, Nelson Muntz sort of way to get a rise out of him. At one point, Burrow longingly discusses with a teammate the prospect of dunking into a cold tub.

“You feel like a zoo animal sometimes when people are just looking at you and taking pictures; it’s all very weird,” he says a few minutes later while unpacking a Tupperware container of Szechuan-dressed chicken, brown rice and broccoli prepared by the team nutrition staff hustling behind a stretch of buffet trays stocked with roasted vegetables. Like most of what Burrow says, the observation seems neither good nor bad to him. He’s not complaining about life as a megastar; he just doesn’t like going places where he has to turn down autograph requests. He doesn’t like other people being nervous around him. He rarely does interviews or podcasts outside of his league-mandated responsibilities. Four years ago, during his first season at LSU, he could walk from Tiger Stadium across the street to his car without security. A year later, amid a national title run, he gave serious thought to hiring a full-time bodyguard. (And, yes, as he discusses his discomfort with being relentlessly gawked at, a reporter breathlessly records his lunch order.)

He is at peace with this existence, one encapsulated perfectly by this shoot. Before his arrival, this is the dark, cavernous ground floor of a parking garage. Burrow arrives skeptically eyeing this artificial world of heat and light and sound, of blaring music and constructed grandeur that required the work of a local fireworks specialist. Then, with cool indifference, he ambles inside that world and blends in seamlessly. Absent any effort, Ordinary Joe becomes that grandiosity. What better symbol for a player who had so innocently and unexpectedly stumbled into megastardom, first in Baton Rouge and then in Cincinnati? Incredible yet incredulous. As a city awaits an encore performance to last winter’s magical run, is this the genealogical makeup required to deliver once more?

Just a few days before Super Bowl LVI, Burrow sent a text to his closest confidantes, confirming their weekly ritual was still on. His firm grasp on sanity amid sudden, uncomfortable fame depends in part on Xbox Live nights. That’s when the boys from Athens High all hop on. These days it’s Star Wars Battlefront II, but last winter it was Grand Theft Auto V’s fist-fight death matches, where they would embody their digital avatars and beat the hell out of one another while trash-talking over their headsets.

“That’s what I look forward to during the season,” Burrow says. “Get in on Monday, watch the film, then get away from football a little bit. Hang out with those guys.” As Burrow explains this, it dawns on him that the Bengals’ status as reigning AFC champions has earned Cincinnati two Monday Night Football appearances this year among their five total prime-time games—that’s after they had just one (a September Thursday Night Football victory over the Jaguars) last season. It will wreak havoc on the Xbox schedule, but special accommodations will be made to fit in game night.

In this space, everything is like it was before LSU, before the national title game and the cigar, before they couldn’t go to the bars without a Burrow-hunting Snapchat mob flooding the place. Here, those surrounding him won’t hesitate to poke fun at the NFL superstar. They’ll adopt a doofy voice and say, Ohhhh, look at me, big Mr. Quarterback!

This is all part of the contemporary monastic life he’s assumed. After a two-hour workout, he “plays video games, then, when my eyes start to hurt, I switch to TV.” He goes to bed most nights at 9 p.m. and rarely sets an alarm. He vacationed this offseason in Scottsdale, Ariz., where teammate Sam Hubbard has a house, followed by a trip to his childhood home in Athens, Ohio.

He says he spends a lot of time inside his own head. Asked whether he’d be more comfortable in, say, the 1960s, a decade during which the world’s best quarterbacks could toil in relative anonymity, he jokes that the idea that he is a man out of his time holds some truth. Though, he concedes, “The pay these days makes up for it.”

“The only time I ever really feel normal is when I’m in there with the guys in the locker room, [or] I’m talking to my friends from high school or my college friends,” Burrow says. “I meet [new] people, and they’re freaking out or something. [But] I’m just me. And everyone I grew up with is super weirded out by it, too.”

During Burrow’s rookie season he made it a point to sit at a different lunch table every day. He said he was serious about the idea of camaraderie and where it comes from. But after a while, he stopped thinking about it. If there was an empty seat, he just sat there, not looking up to see who else was around.

Heading into the 2021 season after a four-win campaign, the team was coiled tighter than ever. So were their games. The Bengals went to overtime twice in the first five weeks, with two other contests decided by three points each. They were an unexpected success story at 4–2 when they traveled to Baltimore on Oct. 24 to face a Ravens team that had beaten them five consecutive times and outscored them 65–6 in their two meetings in ’20. The Bengals throttled their division rivals that day; Burrow threw three touchdown passes among the offense’s 41 points, and the defense sacked Ravens quarterback Lamar Jackson five times. And yet, the following week, on Halloween, they lost to the Jets, one of the worst teams in football, who were starting backup quarterback Mike White. The week after that, they gave up 41 points to the Browns, dropping their record to 5–4.

And so the season went, vacillating between brilliant and cringeworthy, but with an underlying promise evident every week, Burrow says, in the kinds of small moments the outside world couldn’t see. Meals. Meetings. Winks and nods around the building. When coach Zac Taylor would go home at night, he’d tell his wife, Sarah, about all the little inside jokes developing in the locker room.

Maybe it was the way veteran tight end CJ Uzomah went into the facility every day with the intention of messing with receiver Ja’Marr Chase. During otherwise banal practices, Uzomah would just stare at the soon-to-be Rookie of the Year. Chase hated getting stared at. They would crack up afterward (“CJ has been aggravating me since I got here,” Chase says, with love).

Maybe it was the way offensive coordinator Brian Callahan would splice in random embarrassing footage of players and coaches into their weekly meeting videos. While breaking up the tired act of film-watching has become a somewhat standard ploy by coaches, Callahan would take things to another level. He did an especially deep dive on Trenton Irwin, uncovering the fact that the receiver had been in a commercial for canned soup as a child and including the ad in a session.

“What’s great about our team is you start to have these little moments with everybody,” Burrow says. “It’s not just me and the receivers or the offensive linemen. I think it’s pretty rare and I honestly think that’s why we ended up winning all those games.”

After a Dec. 12 overtime loss to the 49ers dropped the Bengals to 7–6, they won three of their final four games to clinch the AFC North, including a 34–31 win over Kansas City in Week 17. Against the Chiefs, Burrow threw for 446 yards and four touchdowns—a week after throwing for 525 yards and four TDs in completing a season sweep of the Ravens. It was the preamble to one of the great unforeseen runs in any sport’s postseason history. A narrow 26–19 wild-card win over the Raiders that came down to a last-second goal line stand by the defense. An even narrower 19–16 win over the Titans in the divisional round that was tied with 20 seconds remaining in the game before cornerback Eli Apple tipped a Ryan Tannehill pass in the air, allowing teammate Logan Wilson to intercept it. With one pass, Burrow advanced the Bengals into range for a game-winning Evan McPherson field goal. They recovered from an 11-point halftime deficit in the AFC title game but allowed the Chiefs to tie the score at 24 as time expired in regulation. On the first drive of overtime, safety Vonn Bell intercepted a Patrick Mahomes pass, setting the Bengals up for another game-winning field goal drive.

For his part, Burrow established himself as one of the NFL’s elite quarterbacks. Going back to his breakout senior season at LSU, his mastery of the modern game looked as though it came from nowhere, but it had always existed, waiting for someone to yank it out of him. In 2018, his first year starting at LSU, he completed just 57.8% of his passes for 2,688 yards, 16 touchdowns and five interceptions. In ’19, under a new coordinator, Sean Payton disciple Joe Brady, Burrow threw for 5,671 yards, 60 touchdowns and six interceptions.

The aggressive spread scheme allowed Burrow to maximize his greatest strengths. With near-flawless throwing mechanics and a textbook foundational platform on seemingly every throw, his ball placement is impeccable. He has a fast release (last season it was just 0.19 seconds slower than that of the famously decisive Tom Brady). He is athletic, but in a hyperfunctional way for the position, which allows him to keep plays alive just as efficiently as a more mobile quarterback while maintaining a perfect stance from which to drive accurate passes.

“His pocket movement is Brady-ish,” says JT O’Sullivan, a retired NFL veteran who now analyzes the position for his channel, The QB School. “I think Brady would love to be as good an athlete as Burrow is, and that’s not knocking Brady. What strikes me about Joe is, not only does he have all these great attributes, but he seems to be so comfortably him. And that goes a long way.”

Give Burrow a system with some playmakers and a sliver of open space, and even a defense dropping seven or eight defenders into coverage on every down is susceptible to what Uzomah calls “that swag.”

Burrow’s rookie year ended with a gruesome knee injury (a torn ACL and MCL) in November, with the Bengals 2-7-1. Protection remained an issue in 2021, when he was sacked 70 times during the regular season and the postseason—no quarterback has ever absorbed more than 76 sacks in a year. But the addition of Chase pushed the offense to a new level. Burrow could rifle a ball to his old LSU teammate well before the receiver came out of his break, and Burrow’s ball placement on shorter throws allowed Chase to turn them into long gains. It made the Bengals’ offense nearly impossible to scheme against, leaving the pass rush as an opponent’s lone hope.

In the locker room, Burrow wasn’t much of a speech giver. He says he does not actively seek advice; his father, Jimmy, a long-time Division I football coach, sends Burrow pointers in a text message before every game but never receives a response. Perhaps one of Burrow’s most memorable message to the team throughout the entire season was to dismiss the rallying cry that Bengals fans had adopted during the run: “Why not us?” Burrow thought it was too suggestive of an underdog, a team that was less than. He didn’t see the Bengals that way.

As the postseason run unfolded, the city elevated the Bengals to new levels of celebrity. The kicker was on billboards for a local weather station advertising itself as, “Accurate as Evan McPherson”—and hailing them as saviors. Every win would produce social media and local news montages of grown men weeping, jumping into near-frozen pools with lit cigars in their mouths. There is a special kind of pressure that comes with reviving football in a place as starved as Cincinnati. It was bigger than all of them. Out of their control. A wall of fireworks and flames, noise and light.

His teammates looked to their quarterback and likely saw him retreat within himself. Within his team. Within his small network. And so, the team did the same, burying themselves in one another, in the little things that bound them and made them enjoy coming to work.

Because of the pandemic, Taylor’s kids didn’t get a chance to meet Burrow until January 2022, following the Titans game, more than a year after he was drafted. Burrow and Taylor consider themselves friends more than anything. Coach allows quarterback to be himself, both in designing plays that create a sense of comfort and not micromanaging him as a person. In that way, the two keep each other level. Just as they are devoted to their tentpoles of stability outside of football, they seem to create that repose in one another.

Taylor held on to his own rituals, like the afternoon visits from his family every Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday. Sarah would pile their four kids into the SUV and drive up to the offices with two venti Pike Roasts from Starbucks. They’d all sit and just talk. After the kids were in bed, they’d fall back on reruns of New Girl, which Zac watches to zone out and calm down (he’s seen each episode 100 times, says Sarah).

Sarah remembers waking up the morning after Cincinnati earned its trip to the Super Bowl to a flurry of text messages from friends in the drop-off line at school: Is Zac seriously dropping the kids off right now? He had walked in the door after 2 a.m., then responded to a mountain of congratulatory messages. She never actually saw him fall asleep, and then he was gone by 6, whisking the kids away to school.

“Being gone for a couple of hours isn’t going to dictate whether you win or lose that week,” Taylor says. “But it will matter to your kids and it will matter to you. Make sure that emotional tank is filled up.”

Even Mike Brown, the team’s gruff and reclusive owner, felt the surge brought on by sudden success. In the aftermath of the AFC title-game victory in Kansas City, the then 86-year-old sat at the front of the team bus, in a daze. One close friend of Brown’s said they hadn’t heard a story about him being this happy since the day in 1995 when he walked into a mob at old Municipal Stadium in Cleveland and signed autographs for the fans ripping out bleachers on what was then the Browns’ last day as a franchise. The Browns had fired Mike’s father once upon a time; a sin he has never forgotten.It was all finally happening. Brown had fallen into a generational quarterback from the Buckeye State who took the Bengals’ history of futility as a personal challenge. He had hired a coach whose wife talked about Cincinnati with the affinity most vacationers save for Martha’s Vineyard. While everyone outside the organization was envisioning Taylor’s ouster after a 6-25-1 start, Brown’s wife, Nancy, was busy shopping for Sarah’s favorite scented soap for Christmas 2020.

Whether consciously or not, they all found a separate peace as the entire thing gained an unstoppable momentum, just like their quarterback. They could retreat into family, into themselves, into their big dreams and grand plots, into scented gift soaps and little human interactions that made the weight of what was happening seem manageable.

As a senior at Athens High School, Burrow’s team lost the state championship game, 56–52, to the heavily favored Toledo Central Catholic (a game in which Burrow threw for six touchdowns). That day in 2015 he told the Cleveland Plain Dealer: “[This is] the worst day of my life. Not much more to be said.”

“I remember Joe telling me after that game, ‘This is the worst feeling I’ve ever had,’ and I gotta say I kinda agreed,” says Burrow’s high school coach, Nathan White. “At that moment, it is the worst thing you could possibly feel, you know?”

Before Super Bowl LVI, when he wasn’t working out, recovering or watching film, Burrow began binge-streaming the NFL Network series A Football Life. One episode in particular, on Hall of Fame quarterback Kurt Warner, stuck with him.

Warner, a family friend who played on the Iowa Barnstormers of the Arena Football League when Burrow’s father was the team’s defensive coordinator, said that one of his major regrets in life was not celebrating the Rams’ Super Bowl loss to New England. There is so much good leading up to that moment. Why sit in a corner and pout?

And so, on Feb. 13, minutes after Aaron Donald had spun him around and forced his fourth-down pass to bounce off the turf on the Super Bowl’s clinching play, Burrow revealed one of the critical philosophies culled from his pared-down existence.

“It didn’t come out the way we wanted it to, but I think we still have something to celebrate,” he said.

Burrow danced (albeit awkwardly) at the Bengals’ afterparty, on stage with one of his favorite musicians, rapper Kid Cudi. When he got home he opted not to pick up a football for a while. He stepped away from the game, securing a mindset: What had happened last winter was awesome, not some sad song—losing the damn Super Bowl—to be played in his mind over and over again.

“You just grow and mature and understand that we’re going to lose some games and have some bad days,” he says. “It just so happened that the game was the Super Bowl. . . . You have to learn how to win and learn how to lose. You have to learn to take those losses and move on from them.”

For the Bengals, 2022 will be defined by a resiliency born out of that mindset.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHHHHH.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHH.

ONE . . . TWO . . . FSHHHHHHHHHHH.

After a few minutes, Burrow’s time in the jungle is over. If the feeling now is any indication, we will see him playing meaningful football deep into winter after winter. Another Super Bowl run? Why the hell not?

The heat and the light will always be there now. Burrow understands this. He’ll spend his time systematically approaching it and then backing away, understanding that it is both the prize and the pitfall. When asked whether it might ever start to feel normal, he doesn’t hesitate.

“Never in a million years.”

Watch the Bengals live with fuboTV: Start a free trial today!

• Aaron Rodgers Talks Gratitude, Reconciliation and His State of Mind

• Do Psychedelics Have a Future in Sports?

• Deshaun Watson Allegations Should Stick for the Rest of His Career