The NFL Cast Him Out; He Says That Only Makes Him More Powerful

A few days before each of the Browns’ first seven games last season, JC Tretter visited team doctors to get his right knee milked.

The 30-year-old veteran center would hobble into the training room and holler, “It's time to milk my knee! Let’s go!” Really, it wasn’t lactation so much as joint aspiration: a procedure where, in the case of Tretter’s knee, enough excess fluid was drained to fill upward of two 60-milliliter syringes—or roughly the volume of a double espresso shot, sans dairy. Regardless, it did the trick of relieving the recurrent swelling so he could lightly participate in practice and then play at full speed in the game.

Then a ninth-year NFL veteran, Tretter was no stranger to overcoming bumps, bruises and worse on that specific part of his 6'4", 307-pound frame. In August 2020, for instance, after undergoing arthroscopic surgery to repair a torn right meniscus that he had unknowingly played through for most of the previous season, he fast-tracked his rehab to rejoin the Browns for their opener less than a month later by icing his knee so feverishly that it developed early signs of frostbite.

After tweaking that same knee at the following training camp, Tretter awoke one morning to find it puffed up and incapable of bending. (Hence, the hebdomadal milking.) Yet he remained one of the league’s most durable blockers, receiving a “questionable” designation on the Browns’ injury report for those first seven weeks but nonetheless continuing his streak of never having missed a start due to injury since arriving in Cleveland in 2017 (his lone DNP came due to COVID-19). “Very few times was I ever worried about being able to play,” says Tretter, who also clocked more total snaps in those five seasons than all but two centers (Jason Kelce and Ryan Jensen). And so, as concerned friends began hitting him up to ask about his future over the past two-plus years, he would reply by sharing what he saw as the real threat to his time in the game.

“Guys would be like, ‘Oh, like how are your knees doing?’” Tretter, now 31, recalls. “And I always said, ‘My NFLPA job is gonna end my career well before my knees end my career.’”

That fateful time, he feels, has finally come. Released by the Browns in mid-March, four days after he was elected to a second two-year term as president of the NFL Players Association, Tretter hit free agency intending to return for a 10th campaign before retiring. His “short list” of dream destinations was topped by the Panthers, as he has a longstanding relationship with offensive line coach James Campen; the Cowboys, “because I feel like if you’re going to play one last year, that environment would be fun”; and the Vikings, because he cheered for them as a child and “wanted to put a bow on my childhood.” But, Tretter says, none of the seven teams that his camp contacted reciprocated his interest. “Minnesota never returned our call,” he says.

In Tretter’s estimation, finding the reason for this radio silence isn’t difficult. He describes his salary requests as modest, “not at a vet minimum” but “well below the value I bring.” He says his right knee is “fully ready” for game action, having healed itself of the swelling issue by Week 8 last season and requiring no more draining for the rest of the season. Plus, Tretter adds, no club has so much as requested an MRI or a physical to inspect it. This despite Pro Football Focus ranking him as the league’s fifth-best center entering this season.

And then there is how Tretter’s agent explained the lack of movement: “I got a call in mid June,” Tretter says, “and it was like, ‘I didn’t realize how many people you pissed off.’”

(In an emailed statement, NFL vice president of communications Brian McCarthy described Tretter as “a relentless and passionate advocate for all NFL players”; asked for specific comment on Tretter’s belief that his union role factored into his lack of a contract, McCarthy replied, “JC is a free agent eligible to sign with any team. We would refer you to the clubs for any comment.” The Vikings declined to comment; the Panthers and Cowboys did not respond.)

Friends, family and fellow members of union leadership are “frustrated” and “bothered” at Tretter’s ongoing lack of a deal, he says. As his former Cleveland linemate Joel Bitonio recently told reporters at Browns training camp: “When you have a guy that’s top-five, top-10 at center in the league and he’s not on a roster, and he's the NFLPA president … it seems a little suspicious to me.”

Sitting down for breakfast at a Washington, D.C., hotel earlier this month, Tretter admits for a time feeling “somewhat vindictive” toward all the teams who passed on him. “There are teams right now that I would say are desperate for a center based off how camp’s going,” he says. "Still no calls.” But, he continues, his desire to return has faded. “I’ve gotten to the point where I’m going to retire,” he says. “I know what I’ve accomplished in my career and I’m at peace with that.” If some desperate team called tomorrow, he adds, he’d pass.

Part of this peace stems from the feeling that he is walking away after 111 games and 90 starts with his body intact. “Yeah, I have wear and tear because I’ve gotten in probably 5,000 car accidents for my job,” he says. “But in the grand scheme of things, I can play with my kids, I can play basketball, I can lift and run and jump.”

But Tretter, who holds a degree in industrial labor relations from Cornell, is also at peace because of his key role in a much bigger fight. Not since Jeff Van Note in the mid ‘80s has an NFLPA president’s playing career outlasted his tenure as the union’s highest-ranking player, with all 10 subsequent presidents either logging their last down before entering office or doing so shortly thereafter (though some continued their presidency past their prime playing ages). “I took this job knowing the risks,” Tretter says. “I think that’s the price of leadership.”

And so, as he serves out the final year-and-a-half of his term—as allowed by union bylaws—rather than wage a personal war against the team owners who sent him into early retirement, he’d prefer to discuss plans for rallying his roughly 2,500 fellow union members against them. How? By continuing to build bridges within the NFLPA’s notoriously fractious ranks, with an eye toward tapping what he sees as an untapped well of collective power.

“Now I’ve got a bunch of free time on my hands,” he says. “I would argue I'm going to accomplish more in the next 18 months than I would have ever gotten close to playing football during that time.

“I’m very excited about what’s next.”

This offseason was not the first time Tretter faced a career crossroads. Near the end of his sophomore year at Cornell, the combination of a torn left meniscus and ongoing friction with his position coach led Tretter, then a high school quarterback turned tight end, to seriously contemplate quitting football and trying out for the Big Red basketball team. But after much soul-searching, he instead doubled down on his commitment, typing a letter to himself one sleepless night and printing it out to post above his door, as a reminder of the work yet to be done. It began:

Today, May 7, 2011, at 2:35 am, you have decided that you will be a professional athlete. You will get drafted, and you will play in the NFL until you want to stop.

Tretter lived–and ate–his commitment: He gained 57 pounds in two years at Cornell as he switched from tight end to left tackle. The Packers drafted him in the fourth round of the 2013 draft, only for him to suffer a broken fibula and tear ligaments in his ankle 10 minutes into his first NFL practice. But Tretter’s resolve didn’t waver: Returning from the injury, he converted to center and three years later became Cleveland’s starter, signing for $16.75 million, with $10 million guaranteed. “My personality is like, if I'm going to do something, I put all my chips on the table,” he says.

Such was the case when he tossed his helmet into the race for union president in early 2020, despite being on just his second season as one of the Browns’ alternate player representatives. “I realized that if I want to invest my time, I really want to invest my time,” he says. “Plus, with my background, I felt like if there’s anybody to do it, it was probably me.”

The election was held at the union’s annual convention in Key Biscayne, Fla., just four days before voting closed on a new collective bargaining agreement with the owners. Running against linebacker Sam Acho and defensive back Michael Thomas, Tretter amassed a majority of first-ballot votes among the NFLPA’s 32 team representatives, even winning over one of his challengers: “I saw this man in our meetings, I heard the questions he would ask, the ideas he’d bring to push our union farther, I already had it in my mind, that’s a strong brother right there,” Thomas says. “Then [I learned] what college he went to and that he actually studied union law. I was like, ‘Shoot, that’s a no-brainer.’ The night before the vote, I told him that: ‘Hey, bro, nothing but respect. You’re the man for the job.’

“From then on, he hit the ground running.’”

A few days later, it was announced that the players had approved the 10-year CBA, by a narrow 60-vote margin, despite vocal dissent from stars like Tom Brady, who opposed lengthening the season to 17 games. Tretter was taking over in, as he put it, “a very contentious time.” Then suddenly COVID-19 hit and the union was unexpectedly back at the bargaining table, at odds with the league over playing conditions. “If you were doing the computer simulations, a lot of times that goes poorly, being that split going into new negotiations,” says Tretter. The hectic start to his presidency, he says, was a “violent, two-hand shove into the deep end of the pool.”

As the NFLPA and the NFL began working on an economic and safety plan for the 2020 season, Tretter rallied his peers in a way familiar to many during quarantine: He sent them a Zoom link. “We started doing leaguewide calls for not just players, but wives, where we’d have our doctor on and they could ask any question,” Tretter says. “I think that started the rebuild of people feeling good about the union, where we were giving them access to information.”

A flicker of the possibilities of a unified NFLPA emerged that July, soon after the league announced its intention to open its training camps on time later that month. In reaction to the news, Tretter says, he received a call from a “star player” asking him to attend a meeting that the player had organized alongside “probably 25 other big-name guys” to discuss their concerns with the NFL’s proposed health and safety plan. (Tretter declines to name any of these players absent their permission because, as he puts it, “you get labeled as an organizer, that doesn’t help your career.”) Of particular issue to players were the number of preseason games, the length of the reacclimation period to training camp and a lack of daily COVID-19 testing.

The result of that meeting was what Tretter describes as “one of the greatest things our union’s done,” a massive social media blitz at noon on a Sunday in which the likes of Patrick Mahomes, Russell Wilson, Aaron Donald, Myles Garrett, JJ Watt and others tweeted messages of solidarity en masse, along with the hashtag #WeWantToPlay. Some, like Drew Brees, even went so far as to state the obvious threat: “We need Football! We need sports! We need hope! The NFL’s unwillingness to follow the recommendations of their own medical experts will prevent that. If the NFL doesn’t do their part to keep players healthy there is no football in 2020.”

In Tretter’s recollection, commissioner Roger Goodell informed the union by the end of the day that league owners were willing to agree to a longer ramp-up timeline than their proposed 18 days (they settled on 20) and to cancel preseason games outright. (The NFL did not dispute this account of the talks.) “We’ve been fighting about [these issues] for months, and all of a sudden a group comes behind us and is like, ‘No, this is seriously a problem,’” Tretter says. “And [the NFL is] like, ‘O.K., just take it. Please leave us alone.’”

But what makes this coordinated action stand out for Tretter isn’t the short-term concessions that it helped players gain; it’s the hope it fuels of even bigger gains in the future. “That’s what I want guys to see: That wasn’t a strike,” he says. “That wasn’t you losing a paycheck, that was you firing off a 20-second tweet, and it gave us instant wins. We’re not always asking you to sacrifice a million dollars and strike for half the season. Sometimes, if we can just organize guys, we can make gains with, in the grand scheme of things, minimal effort.

“Having that many star players be involved in a union fight we haven't seen before. And if we’re somehow able to re-create that model, everything changes.”

There is no workers union quite like the NFLPA, at least not in terms of the obstacles to mobilization embedded in its very existence. It has more than twice the number of dues-paying members as the MLBPA and is five times the size of its NBA counterpart. The pay gaps stretch from the $705,000 league minimum to the $150.8 million that Aaron Rodgers is guaranteed from the Packers over the next three seasons. Plus football’s short average career lifespan and endless physical toll incentivize players, through no fault of their own, to act in their best interests while they can.

“That’s the tough thing about organizing: getting a bunch of people with different motives aligned,” Tretter says. “Some are just like, I’m happy to be here, so if they tell me I’m working 19 hours a day, I’ll do it, because I want to be here. Then you have guys who are a little older and have been there and are like, wait, some of this stuff should be better for us.”

Tretter concedes that all of these factors make it difficult to “motivate the masses” around what he characterizes as “niche” topics affecting small percentages of members. One such example in his mind is the franchise tag, a fixture in CBAs since the first NFL-NFLPA agreement nearly three decades ago. “Would we love it if the franchise tag wasn’t there? Yeah,” Tretter says. “The issue is 99.9% of guys are never going to be tagged.”

Later on, Tretter employs the same percentage when asked whether he puts further overhauling the league's discipline policy in the same basket: “With discipline too, 99.9% of our guys are never going to be on the personal conduct spectrum.” The ideal system, he continues, would involve “a neutral prosecutor who would bring a case to a neutral judge, whose decision was binding.”

As it was, the first test case of the most recent CBA’s new procedures—which lessened commissioner Roger Goodell’s punitive power by creating a jointly appointed, neutral disciplinary officer to levy suspensions on cases prosecuted by the league, yet retained the league’s ability to designate who will hear any appeal on that disciplinary officer’s initial ruling—resulted in an 11-game suspension and a $5.69 million fine for Browns quarterback Deshaun Watson due to numerous allegations of sexual misconduct. (Watson has denied wrongdoing.) Asked whether he had any personal misgivings with the union’s representation of Watson against the league, Tretter says, “My personal feelings are irrelevant. It’s our duty as a union to represent our members, ensure they have a fair process and defend our CBA.”

There is one key issue on which Tretter does see a clear path forward: guaranteed contracts, which unlike in the NBA and MLB rarely exist for NFL players. “With Kirk Cousins, we missed a boat,” Tretter says of the Vikings quarterback, who in March 2018 signed the league’s first fully guaranteed deal ($84 million). “He had a ton of leverage, got it and no one came behind him.” Indeed, it wasn’t until the Browns promised Watson $230 million in March that the second came along. While that particular guarantee is fraught for many reasons, Tretter hopes it starts a trend.

“If your answer is, we should go into a CBA fight for guaranteed contracts, that’s not what basketball did,” Tretter says. “They did it without having to go to the table. They did it because individuals stood up. That’s what I’d love to see. If you’re [Broncos quarterback] Russell Wilson, and the team just gave the farm for you, and you’re coming up on a new contract with one of the richest new owners in the league who has plenty of money … it would be better for the union if you held out on the idea of, I should have a guaranteed contract.

“Do I think it’s going to go from quarterbacks having guaranteed contracts to centers? No. But when the next Aaron Donald comes up for a contract extension, and he says, ‘I’m as valuable as a defensive player as you could possibly find,’ does he have a better chance? Yeah. And all of a sudden the premier positions are getting guaranteed contracts: quarterbacks, D-ends, corners, receivers. Could I see a world where that’s in the cards? Yeah, I could. There’s a path.”

To Tretter, the #WeWantToPlay action proved that prominent players can lead the way on union issues, too. Another example surfaced over the 2021 offseason, when nearly two dozen teams’ rosters put out statements declaring their intentions to boycott voluntary workouts. (Among these teams, Tretter notes, were the two future Super Bowl LVI participants, the Bengals and Rams.) But perhaps the most vocal player in this fight was Brady, who issued pleading calls for unity on union Zooms and held rogue practices outside of the Buccaneers’ facility in pursuit of negotiating laxer OTA rules with teams.

“Giving players a voice, letting them dictate their working conditions, that is agitating to the league,” Tretter says. “If I can build programs to grow those three pillars—players using their voices, players being engaged and players dictating their working conditions—I think you increase the likelihood of more things like that coming in the future.”

Over the first half of 2022, the number of union election petitions filed to the National Labor Relations Board—most by grassroots campaigns formed outside traditional union bureaucracy, most led by women—had more than doubled compared to the same period last year. Whether Amazon factory employees or Starbucks baristas, Trader Joe’s clerks or Apple retail staffers, people everywhere are banding together to attempt to reclaim ground from management.

In February, while out in Los Angeles for Super Bowl week, Tretter and a handful of NFLPA officials visited the picket line outside a nearby desserts plant owned by the multibillion-dollar company Rich Products. There, for the past three-plus months, more than 100 predominantly Latina laborers had been striking around the clock in search of better wages and working conditions. Posing for pictures, giving a pump-up speech from a pickup truck bed, asking workers about their fight, Tretter was awed by the scene.

“I wish more guys would go to those types of events to see,” Tretter says. “These people have nothing and are willing to risk it all, because that’s what respect looks like to them. There was no wavering, no caving. It was, ‘We are going to stay out until we get what we’re asking for.’ I thought that was so powerful and inspiring. Seeing a group of people barely making minimum wage to stay out for months without a paycheck, it just puts everything into perspective. Our guys should be much more capable of not needing to go to work if we wanted to do that eventually, and saving up their money to do that.”

Historically the NFLPA and other major men’s league unions are seen as existing outside this broader worker ecosystem, content to count their millions and unconcerned with building broader coalitions across all workers. The truth is that they’re not totally on the sidelines; in addition to on-site visits and other public statements of support for labor fights, NFLPA officials have also offered behind-the-scenes consultations on strategic matters to leaders at unions representing employees from Starbucks, Amazon and other companies.

“I think the more that we intermix and intermingle with regular workforce unions, using our resources and our capital and our platform to help them, is better for us,” Tretter says. (In its 2020 tax filings, the NFLPA reported nearly $160 million of net income and more than $620 million in assets.) “No worker for one job should be like, you have enough, you should be happy with that. We’re workers. We’re fighting for the same things. We should all have the hope that we’re all getting better.”

Before Tretter can hope to extend the NFLPA’s influence outward to help raise the tide for all boats, though, he first must turn inward. Here he sees a shining example in both the WNBA and NWSL, describing the respective players associations for those women’s leagues as “very inspirational for both their willingness and their execution in fights.” In particular, he says, “The WNBA players are very good at holding a message and being unified across their locker rooms.”

While the NFL’s current CBA contains a no-strike clause that prohibits players from officially voting to walk off the job (and owners from locking them out) until it expires after the 2030 season, they are plenty free to pursue ad hoc actions in the interim to chip away at the league’s leverage. “We are eight years out from the next CBA fight,” Tretter says. “And a lot of people look at that as like, “O.K., well, let's just ride it out until you have to start thinking about the CBA. No, we can really push the envelope more now. We can't strike. But we can creatively cause chaos.”

Blasting out a unified message on Twitter has already proved to be effective. Another idea that Tretter and other NFLPA officials have been brainstorming comes straight from the playbook of the WNBPA, which has staged coordinated postgame media blackouts in which players speak about only a single topic, whether Black Lives Matter or bringing Brittney Griner home. “If 32 [NFL] teams, every player, to a player, said, ‘I think the biggest issue to talk about is the fact that blank,’ and that was the only quote anyone in the media could get for an entire game cycle … those are things that, if we could pull off, I think are huge, huge swings that are problematic for the league. What scares them most is players rising up and being unified without them knowing about it.”

“It’s about finding creative ways where we can get buy-in,” he continues. “Skipping the offseason is a huge leverage gain. Maybe it’s not possible. Maybe we have to find 10% leverage gains to get up to that level. But that’s the nature of leadership: understanding your membership and understanding what your membership’s going to do, and then thinking, ‘How do we get to where we need to go in that prism?’”

To that end, Tretter wants to conduct “more surveying, more polling and give [players] more of a say of what's going on at their facility, on their teams,” he says, all geared toward earning what he characterizes as “lifestyle wins that sometimes get lost in the shuffle amid CBA times.” He also plans to devote some of his newly found free time to visiting teams and engaging with players during the season. “It’s better one-on-one,” he says. Another idea in the works: a golf retreat, dubbed the NFLPA Classic, scheduled to tee off in the Bahamas in March. “That’s bringing guys together that otherwise wouldn’t be involved with the union,” he says. “You start building that trust, and that togetherness. I think these people start seeing the union in a different light, less of always an ask and more of a give-and-take.”

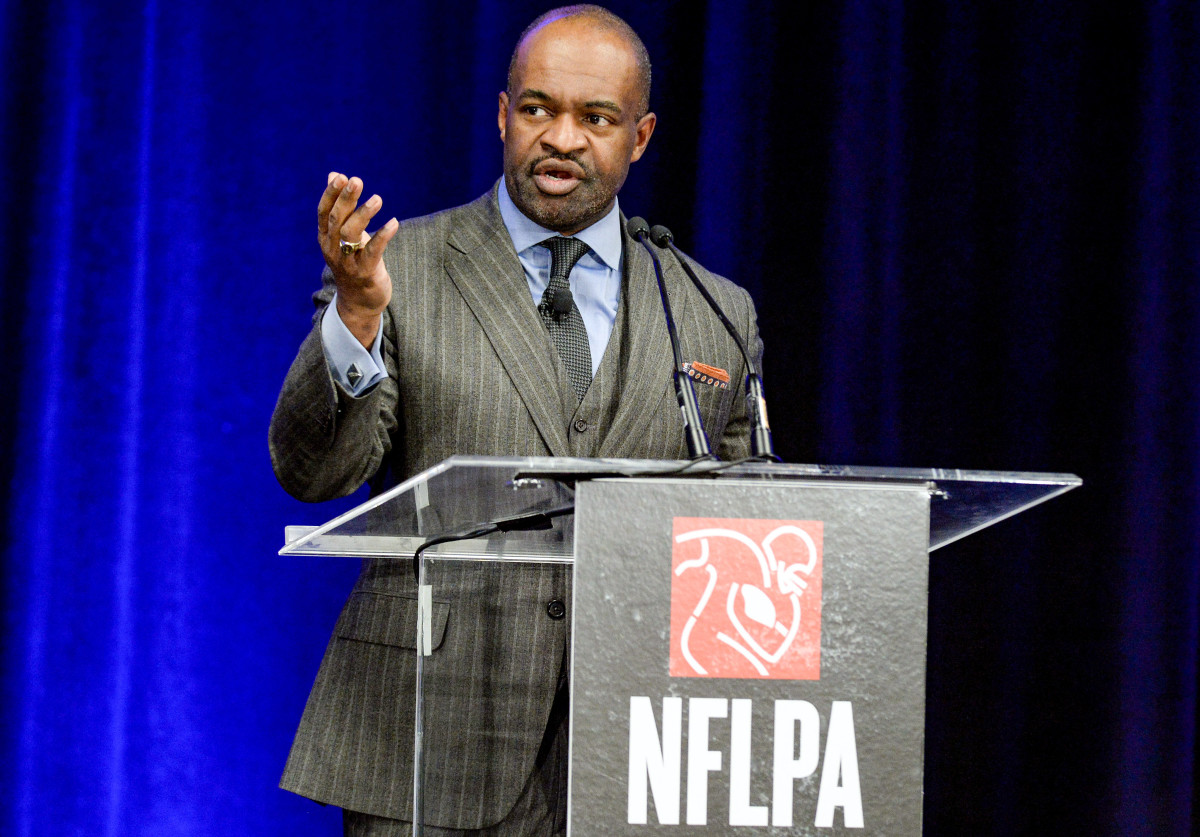

There are other pressing issues too, namely the quest to hire a new executive director to replace DeMaurice Smith, who has held the role since March 2009 but agreed to serve his final term (of a yet-to-be-determined length) after the NFLPA’s board of representatives voted to retain him last fall. Asked about the current state of the process, Tretter declines comment other than to say first that the union has hired a search firm, Russell Reynolds, to assist him and the rest of the executive committee in finding candidates; and second that it is his intention for the position to be filled by the time he steps down as president.

During what he describes as “the most hectic week of my presidency,” when the omicron wave hit last December, Tretter recounts juggling NFLPA business while participating in walkthroughs at Browns practice. “I was like, ‘Baker, I'm not gonna snap, hold the ball, I have to be on this call,’” Tretter says of the former Cleveland quarterback. But now he can devote himself fully to the union: He and his wife, Anna, recently moved their family from Cleveland to the northern Virginia suburbs so he could be closer to NFLPA headquarters in downtown D.C., where staff are setting up an office for him. “I might be delegated to coffee guy,” he says.

Amid all this, Tretter also plans to set aside time to write himself another letter, just like he did in college more than a decade ago. In it, once again, he will list out everything that he hopes to do next—as a father and as a husband, yes, but also as a union president. “And maybe the things that I accomplish in the next 18 months, I don’t get to see the end result of any of them,” Tretter says. “But part of the job is being O.K. with that. The job of the president is to push the ball down the field and to get this stuff done so it’s easier for the next guy, and the next guy and the next.”

That is why, when he is finished writing, he will print out the letter, frame it and put it on his desk at the NFLPA office, as a reminder of all the work yet to be done.

• Why NFL Teams Spent Wildly on Wide Receivers This Offseason

• Joe Burrow and the New Normal

• The (Not Always) Great Tua Debate