Raising Two Kelces

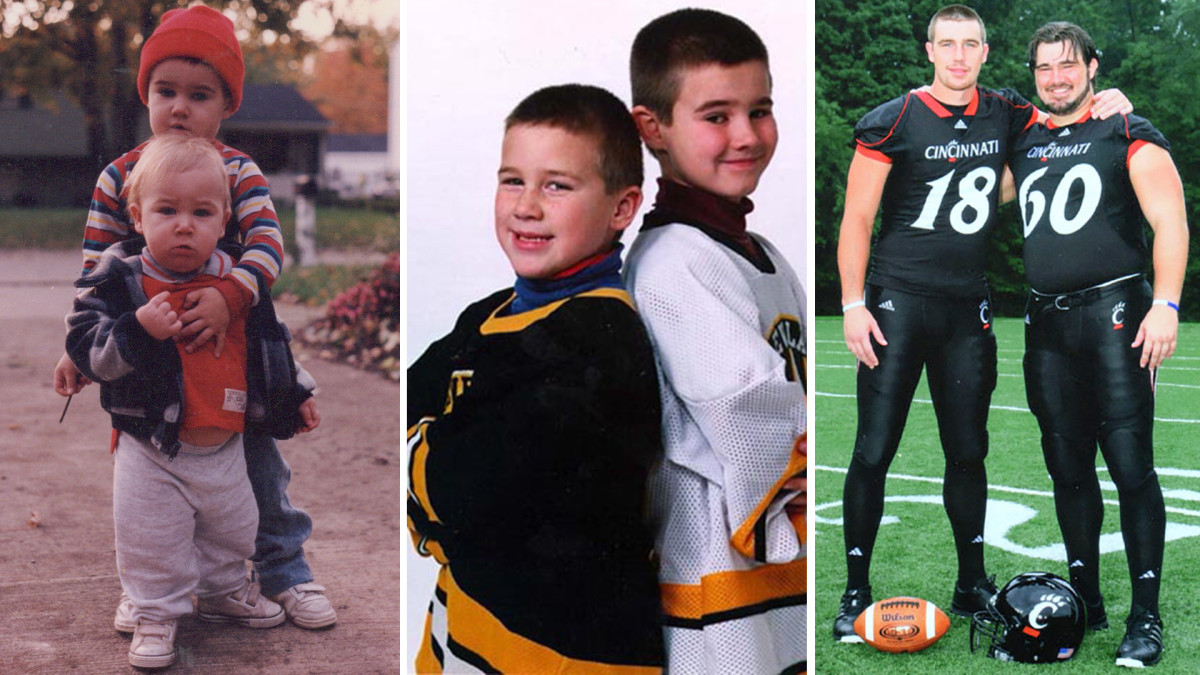

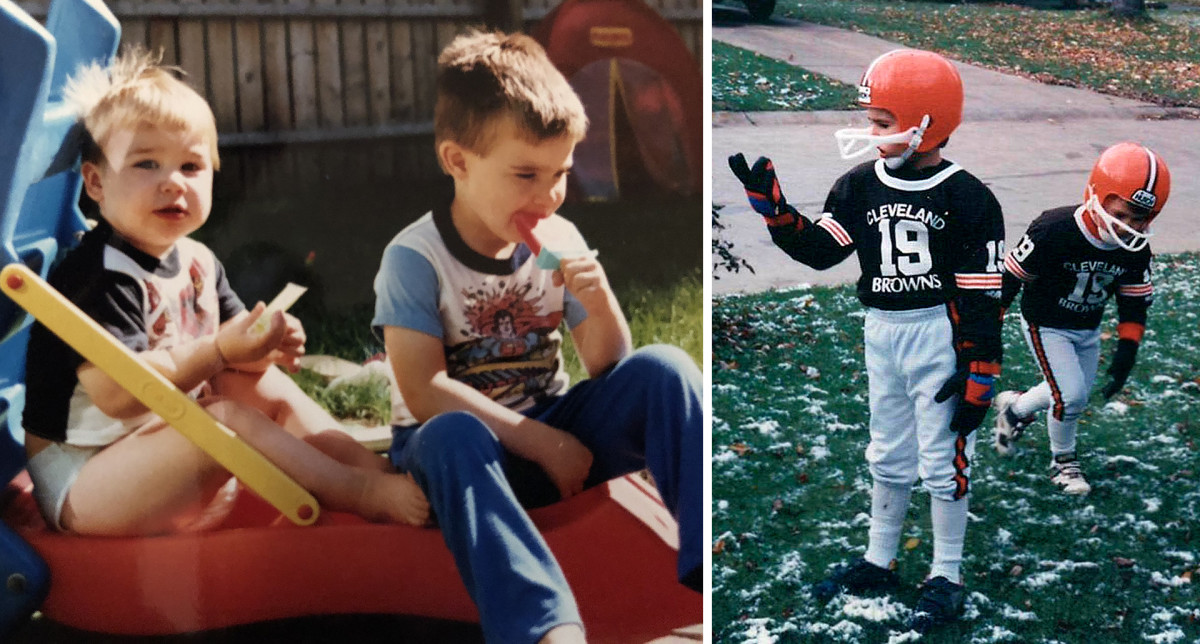

Long before the NFL and the history that is still being made, Donna Kelce watched her boys play every sport imaginable. Jason, two years older than Travis, led both into lacrosse, hockey, baseball, basketball and, of course, football, the sport that connects them all, even now. Especially now.

Truth is, their mom preferred they go in another direction. While raising them in Northeast Ohio, she pushed both not to play in Pop Warner or other youth football leagues, because she worried they weren’t organized enough. She said neither would be allowed to play until seventh grade. When they reached that age, both immediately chose football. Both starred in college at Cincinnati. Both made the NFL.

In the ensuing years both won a million games. Both won Super Bowls—Jason triumphed after the Philly Special clinched the Eagles victory in Super Bowl LII; Travis won his two years later, after a fourth-quarter comeback, with the Chiefs. Kansas City has advanced to the playoffs every season since 2015. After its triumph, Philadelphia returned in four of the next five seasons. Travis has played in 17 postseason games; Jason has been in 10.

Over time, this meant some wild travel days for Donna, logistical puzzles solved, brothers supporting brothers from across the country and no chance they would clash against each other in the playoffs, unless it was in the final game of that particular season. The likelihood of that happening remained low.

Until Sunday. Donna Kelce had to choose which games she would attend this postseason, except for in the non-Kelce wild-card round. For the divisional games, she watched the Chiefs hang on to beat Jacksonville while Patrick Mahomes injured his right ankle. For the conference championships, she watched the Eagles batter the 49ers into the offseason. When, later on Sunday night, Kansas City narrowly edged out Cincinnati, the improbable had happened. Her sons would both play in Super Bowl LVII, an NFL first. Brothers have played with each other. Brothers have coached with and against each other. But never before in league history have two players played against each other.

Perhaps you’re already sick of this story line. You know who isn’t? Donna Kelce. She’s elated. And she’s torn.

This may sound strange now, but her boys didn’t win many, if any, titles while growing up. Their teams weren’t bad; they were hardware deficient. Given the age gap, they often weren’t in the same league, let alone on the same team, let alone on opposing ones.

“They didn’t start winning until they were in college,” mom says.

They did win AAU basketball tournaments when they were younger, and bowl games at Cincinnati, but those aren’t the same as this. Jason won the International Bowl and the PapaJohns.com Bowl before Travis joined him with the Bearcats. Together, they made the Orange Bowl and the Sugar Bowl, losing in both. Travis won a Liberty Bowl and a Belk bowl after Jason had graduated and gone to the NFL. Roman-numeral-type games, these were not.

The Kelce brothers did dream, though. They joked and hoped for serendipity to allow both to play on the same NFL team, which they would lead to the Super Bowl, of course. But Jason spent each of his 12 professional football seasons in Philadelphia, while Travis never left Kansas City in his 10 years. “This is the closest they’ve gotten to that dream,” Donna said before the games last week. She laughs. Maybe it’s a nervous laugh. The boys love winning. One will on Feb. 12 for sure. But it will come at the other’s expense.

“My mom’s going to win either way,” Travis said late Sunday night. But that also means she’s going to lose either way. One boy will be elated; the other, despondent.

Donna also recognizes the good fortune baked into her current “problem.” Jason, for instance, considered retiring this past offseason, same as he has in each of the last three years. Before the Eagles triumphed over the Patriots in Super Bowl LII, he worried that Philadelphia might trade him. He turned in perhaps his best season when it kept him instead. He generally gives himself a few months to allow his body to heal, then evaluates whether he can still play to his standard (six Pro Bowls) and how the roster looks. So far, every April, he has decided to come back.

This season, Donna sensed that Jason would return. He liked how general manager Howie Roseman had reshaped the roster. Last year’s playoff loss in Tampa fueled him and his teammates. He liked mentoring quarterback Jalen Hurts, who asked him to break down defensive schemes. “He just had a good feeling about what was happening the year before,” Donna says. “He felt like there was some unfinished business.”

And not just on the field. Believe it: Jason played in his high school’s jazz band. He had always been drawn to all sorts of music. He played a mean baritone saxophone, in part, his mom thinks, because he was one of the only students who was big enough and strong enough to hold it. The band’s director pointed at him one day and said, “You’re my saxophone player,” and that was that. They traveled to Chicago for performances, which paid off when the Eagles’ offensive line decided to make a Christmas album. Donna loved it. Her favorite track was “Santa Claus is Coming to Town” (which is funny since, you know, it’s Philadelphia fans we’re talking about).

This season, Jason played 98% of the Eagles’ 1,151 offensive snaps, giving him nearly 11,000 for his career. He made first-team All-Pro. His wife is due with their third child in February, complicating Super Bowl logistics.

Travis, meanwhile, has not yet considered retirement. He’s winning too much and catching passes from the NFL’s MVP. His Chiefs have now hosted a record five straight AFC championship games. They won three.

This offseason, many saw the Chiefs as a team without its usual heft. Gone were wideout Tyreek Hill and safety Tyrann Mathieu, two of Kansas City’s most accomplished and competitive players. General manager Brett Veach reconfigured the roster throughout the spring and summer, but concerns lingered, even in the Kelce house. Travis, his mom says, considered his teammates family. He didn’t want to see them depart, not from a team that ranked among legitimate Super Bowl contenders. “They were upset that they lost a few players,” Donna says. “But they knew they still had talent. They just needed to find players to catch the ball.”

This season would be different, she decided, but Kansas City would be fine. Donna saw one candidate in training camp who impressed her: rookie running back Isiah Pacheco. She watched Travis interact with Tony Gonzalez, the longtime Chiefs and Falcons tight end with a strong case for best tight end of all time. They became close, like mentor and mentee. Gonzalez schooled Travis on longevity and nuances for fooling defenders while running routes. Travis sometimes wondered whether he could play long enough to approach Gonzalez’s records for catches (1,325) and yards (15,127) by a tight end. He’s currently at 814 and 10,344, but he amassed those numbers in 144 games, while Gonzalez set those marks in 270. “He’s very close with Tony,” Donna says.

This season, with Hill gone, Travis became Mahomes’s exclusive favorite target. The result: 110 catches, 1,338 receiving yards, 12 touchdowns. They hooked up for another TD in the conference championship against the Bengals, moving them past Joe Montana and Jerry Rice for most postseason touchdown catches from a duo. Kelce ended up with 78 receiving yards on seven catches, which was just fine but snapped his streak of seven straight postseason games with at least 95 receiving yards, an NFL record. But he did move ahead of Rob Gronkowski—and behind only Rice and Julian Edelman—for the most postseason receiving yards in league history. He also joined Gronk as the only other tight end with a playoff TD reception in five straight games.

Still, Donna’s boys aren’t really the accolade-collecting types. They want only one thing, and it’s the same thing: Super Bowl rings. Hence last year’s sojourn. Donna woke up at home in Orlando on Jan. 15 and drove to Tampa for Eagles-Bucs, which would be held the next afternoon. That night, she stayed at a hotel near the airport so she could leave her luggage there during the game. She left near the end of the third quarter, took a pedicab to the Uber lot, took an Uber back to her hotel, grabbed her bag and went to the airport.

Her flight was delayed, which gave her time to change from her Eagles jersey into a Chiefs one. When she landed in Kansas City, other passengers told her that Travis had already scored. The Chiefs had arranged for a driver to pick her up—he did, speeding toward the stadium. But her phone was overwhelmed by all the text messages, and she couldn’t open the app with her tickets. A team official rushed down and escorted her to the seats.

This year, that kind of trip wasn’t possible. She looked into flying private in order to attend both conference championship games. It wouldn’t work out, unless she missed the majority of each. So she chose Philadelphia, then watched the Chiefs game from a local bar after the Eagles win. But she won’t have to choose again on Feb. 12. That’s her problem. And it’s a good one, mostly.

She’ll wear the jersey someone made for her a few years ago, the one split between Eagles and Chiefs. She chooses to look at it like this: Her boys, at their respective cores, are competitors. Both took their losses, Travis more often because big brother could overpower him. Now, as the brothers make NFL history, she can’t think of a more appropriate way for that ethos to play out on the largest stage imaginable. Her heart will break for whoever loses. But there’s a flipside to that, too. One of them is gonna win.