Von Miller Is Ready to Return to the Field ... and for His Future Off It

For Von Miller, the past 12 months have been just like his 12 NFL seasons. There were sacks and success, risks taken and payoffs seized. There was another injury and another comeback (and another baby). And, throughout, whether sky high or subterranean low, Miller couldn’t shake the concept that defines him. That will, literally, define him.

It’s legacy, and Miller’s matters to him more than ever now—and in more than one way. The most obvious slice of how Miller will be remembered—as his generation’s preeminent sack master—was actually the part he thought the least about. It mattered, of course. But with 12 seasons (and counting), 123.5 career sacks (and counting) and two Super Bowl rings (and counting), all Miller can do with his football legacy is elevate, polish and enhance.

Miller also wants his legacy to broaden beyond football, to paint the picture of however many seasons, from his start to his growth to his missteps and his triumphs. All point to a man in full and a supercharged existence. That’s legacy, his legacy.

He hopes it will include his foundation, Von’s Vision, which has raised more than $5 million to help kids who cannot afford eyewear get what they need. And leadership, whether in Buffalo for another season with the Bills, or through the pass-rush summit he created seven years ago and the lessons he imparts and absorbs there. And fatherhood. And entrepreneurship. All of it.

Whenever he does retire, though, Miller plans to stay in football. He’s already working on that, having decided a few years ago and confirmed more deeply since, at least internally, that he wants to pivot into becoming a personnel executive. His goal is to (one day) run an NFL team.

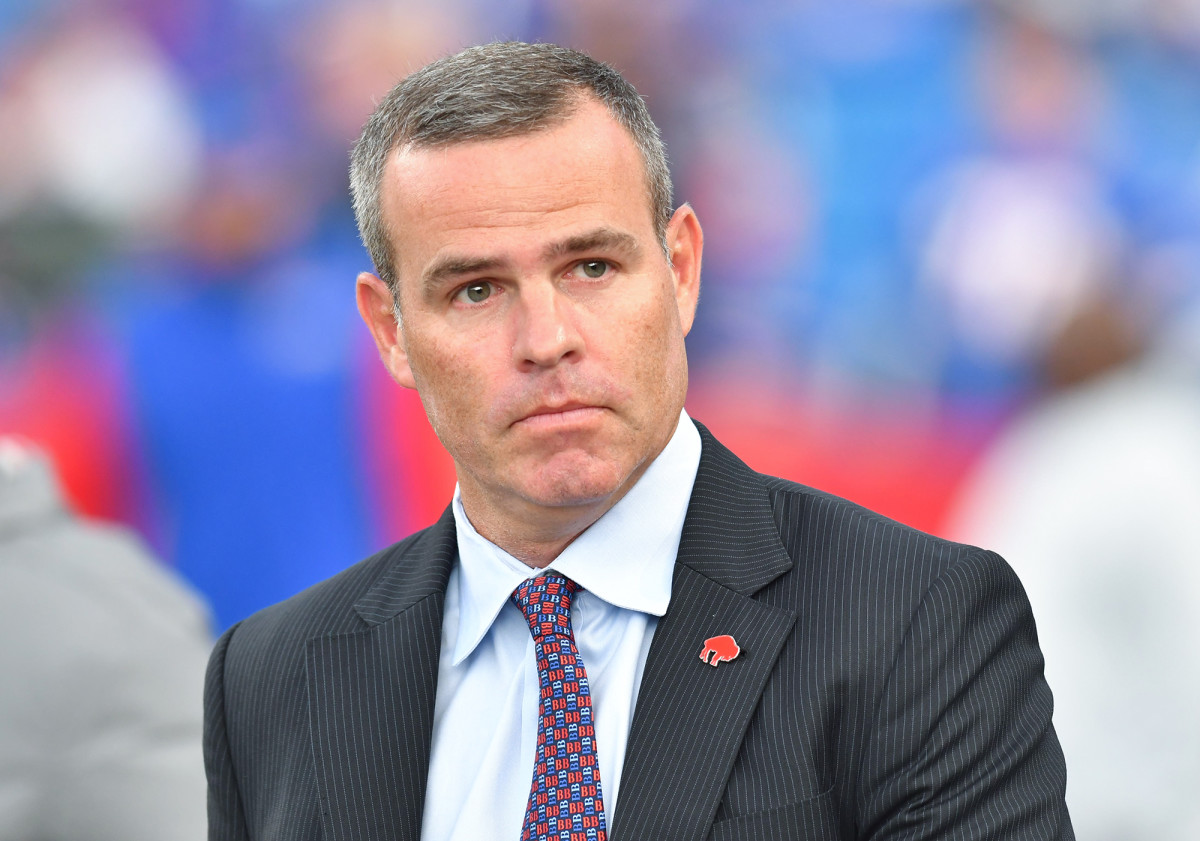

Miller advanced that aim before and after tearing his right meniscus on Thanksgiving 2022 against the Lions. He started dropping by GM Brandon Beane’s office, with increasing frequency in December, for informal chats. Miller assumed a philosophical bent for the sessions, which centered on the best approaches for building football teams and the organizations that support them. The answer wasn’t necessarily the same in every place, Beane emphasized, due to the array of franchises and their variance in operating, which is wider than might be obvious.

Beane would ask Miller questions. Like, for instance, “If you get an opportunity to run a team that’s limited on resources, what would you do?” Followed by, “How would you elevate what’s possible?”

In Beane, Miller began to see his future. Here was a general manager who scrapped upward, who worked hard and shaped a vision and rose, in Carolina, from personnel grunt to director of football operations to assistant GM. Beane then combined his bolstered résumé, his work ethic and his vision to win over the Bills, who hired him as general manager in 2017. “You have to put in more hours than the quarterback,” Beane told his pass rusher.

“Didn’t scare me off,” Miller says. “And I didn’t perceive it as work. I perceived it as things I thought were cool, that I’d be excited to do.”

This revelation sent Miller in the usual direction, toward a rabbit hole of sorts. He ruminated on team structures as they related to both personnel and organizational aims. He pondered what he might “borrow” from his various NFL stops (Broncos, Rams, Bills) and what he would decide to leave behind. He thought back to his time around the executives for those teams, or others he knew personally, from John Elway to Les Snead, John Lynch and George Paton. Miller mulled how their styles compared and contrasted, what worked well, what did not. He wondered whether teams should emphasize the importance of mental health more and the resources available to players. Perhaps the same sentiment applied to executives, especially those who sleep more at their office than at home.

As often happens with Miller’s brain—picture the world’s largest, most intricate and most diverse web—everything started to connect. From early outsized success (drafted No. 2 by Denver in 2011) to early missteps (a suspension for violating the league’s substance abuse policy) to how he overcame the latter to make the former worthwhile.

Haven’t those past 12 seasons—all in football, the second half grounded in unending growth—been preparing him for this second career all along? Of course they have. Miller often found his mind drifting backward, toward his circuitous path, everything that had to happen for him to happen. He doesn’t mean that in a football sense, even. He means those events shaped the man and person and human being he is becoming. Football is a central tenet there. But it’s not the only one, and just being able to recognize that spoke to his evolution, all that growth.

He was looking back, Miller realized, to ascertain what worked and what made him happy. When he better understood what drove his success and simply stayed wherever his mind took him, the realization dawned. The introspection could drive him forward. Then he amended that to would drive him.

Miller owes the dawning, in part, to someone he can no longer thank. When the Denver portion of his career spiraled from triumph (Super Bowl 50) into losses, rebuilding and serious injury, he started to meet with Trevor Moawad, one of the first sport psychologists to work with elite athletes on the deepest level, addressing what too many often ignored. Moawad taught him to embrace gratitude, to realize that he had already done more than young Von Miller would ever have expected. To climb back, he needed to start there, with himself, at previously unexplored depth. When he did that, bigger and bolder possibilities revealed themselves to him. That led to even more introspection, and that led to legacy, his latest obsession.

“I’ve been thinking about this for a second now,” he says. “And then it hit me. I’ve been about player-evaluating my entire career, even in high school. I’m not a contract guy. But when it comes to building a team and getting the right teammates and even the cafeteria workers and mental health therapists and trainers and equipment guys …”

Miller sighs a satisfied sigh. “I know what championship infrastructure looks like.”

He’s not wrong. Snead, the Rams’ general manager who loved his time with Miller, offered an honest appraisal of the pass rusher as a future personnel executive over text message. He hadn’t considered Miller in that role specifically. But when prompted, Snead saw how the person and his long-term aims were perfectly aligned. As a player added late to a championship roster, Snead was struck by how Miller embraced the Rams’ collective mission. That embrace pushed Miller’s teammates, particularly in the playoffs. It also, Snead wrote, projects well into the evaluation space.

He added, “Players like Von have a sixth sense of what a collective that can earn special looks like, feels like and smells like … and they know how to push and pull the collective toward the mission. … This would be the superpower he could tap into as a GM.”

His various stops helped bolster that sixth sense, and in more than one way. Miller’s professional football career is Where’s Waldo? adjacent, in an NFL sense and an off-field one. He moved to Denver, won Defensive Rookie of the Year in 2011, made first-team All-Pro (three times), won a Super Bowl, was traded to the Rams, won another Super Bowl and left for Buffalo, where he predicts—“This is Von Miller! I make guarantees!”—he will add another ring.

He’s won team MVPs, a Pro Bowl MVP and a Super Bowl MVP. He made Pro Bowl nods routine, with eight and counting. He haunted Tom Brady’s dreams and reality. He returned from injuries and far ahead of typical rehabilitation schedules. Already, despite a significant number of games missed due to injury, his career sack total ranks 19th since the stat became official in 1982. With just 19 more, Miller would pass Michael Strahan for the sixth most. (On Pro Football Reference’s unofficial list of sacks since ’60, he is 27th and could pass Strahan for 10th.)

There’s only one problem with that: Sack standing isn’t what Miller truly wants, not even when just considering the football portion of his legacy and aims. He wants to hold that Lombardi Trophy overhead again, as a Bill, preferably more than once.

The good news, for Bills Mafia, anyway, is that Miller Time generally coincides with the postseason. He’s tied with Charles Haley—a five-time champion—for the most sacks in Super Bowls (4.5 each). The Rams wouldn’t have won their championship without adding him midseason and deploying him for 4.0 sacks and 18 pressures in that playoff run alone. The Broncos wouldn’t have won their title if they hadn’t built around him.

Miller wants—no, believes—he will do the same in Buffalo, the franchise he never expected to play for … until it happened. After a divisional round exit in the 13 Seconds game in January 2022, the Bills went into the following offseason hoping to upgrade on defense—specifically, their pass rush. Dealing with Patrick Mahomes in the postseason every year will do that to a franchise. Buffalo did more than call and more than court. In fact, when Miller looks back at that stretch, he marvels at Beane’s explanation for how Miller fit into his vision. Miller believed him, and that belief, coupled with a six-year contract worth up to $120 million with more than $51 million guaranteed, sent him in an unexpected direction.

He had just won his second Super Bowl. Had just had his second child, another boy (Victory), who was born exactly seven years after his first title. Soon, he celebrated his 34th birthday. In an overall life sense, he was still young but wise enough to see more impactful events ahead. In a football one, he was old, or older, close enough to retirement age that of course he heard the whispers that his skills had diminished.

Miller ended those in Week 1, only seven months after Super Bowl LVI, against the very teammates he had triumphed alongside. In that game alone, he recorded two sacks, three tackles for loss and three quarterback hits on his old buddy, Matthew Stafford. For the first 11 games, Miller wrecked—offenses, quarterbacks, souls. He ranked among league leaders in quarterback pressures (45) and pressure percentage. He also added 8.0 sacks to that tally and would finish the season as the ninth-highest-rated pass rusher, according to Pro Football Focus.

But he stops short of saying that it mattered, deeply, to him, that he proved any so-called doubters wrong. What mattered was what he proved to himself. “It showed me that I was still an elite player in this league,” he says. “I still make plays and run around and do things like the young guys. And my time has not passed.”

Asked whether he doubted any of that before last season, Miller says that he did not. “But it reinforced to me, ‘Hey, I still belong,’ ” he says. “It was refreshing for me.”

On Thanksgiving, though, there would be no thanks. The Bills’ defense, so formidable early into the season, had 12 different players miss at least one week. And not just any players, but cornerstones, such as safety Micah Hyde, cornerback Tre’Davious White, defensive tackle Ed Oliver and linebacker Matt Milano.

Miller woke up sick that morning, his body already sore from the brutal Sunday night to Thursday turnaround. He did not feel like himself, and he considered not playing at all. But he figured he could at least start the game and maybe add a sack or two, despite the mucus, wheezing and body chills that announced a cold or flu of some sort.

When the game kicked off, though, he felt … great. He ripped off several “good rushes” and went for another, readying to turn upfield when that right knee buckled. Meniscus, torn. In film review, he noticed a blocker had stepped on his foot, so it didn’t release correctly, hence the buckling. “Freak accident,” he shrugs. “You play football long enough, it happens to you.”

Buffalo’s season was never the same. It ended in the divisional round of the playoffs, in a lackluster performance at home against Cincinnati. Miller focused on the positives, such as his children and his documented injury history, even when doctors discovered an ACL tear in that knee while they repaired his meniscus. Still, he had ACL surgery in January 2013 and still played at the beginning of the preseason, back in under eight months. His outlook was improved now, his mindset more secure, and, from both, his legacy obsession began to sharpen into focus. Don’t feel sorry for me, he told friends. Don’t say, I hate it for you.

“We think if everything goes well with rehab, we'll have him for most of 2023,” Beane told reporters. Miller, in a follow-up FaceTime call last week, told Sports Illustrated that he’s on track to play Week 1, but would understand if Buffalo was extra cautious to ensure his availability when he’s most needed, whether through reduced snap counts or a later start to his season. Either way, he says, “I promise you this: I’ll be ready.”

Miller dived into rehab and legacy enhancement simultaneously, which produced even more connections. He thought back to his youth team in fifth grade, and how he knew, intrinsically, the immersive brotherhood he wanted to create. Of course he cared about his first love—sacks. But the meaning of football broadened for him. So he decided to “put my fingerprint” on the game that had put its fingerprint on him.

He played more golf, for balance and serenity. He spent more time at home. In doing all that, the soul of what football meant returned. “This is my life,” he says, just not in exactly the same way as before.

Miller hopes to play as long as Julius Peppers, who thrived for most of 17 seasons. He’ll amplify the brotherhood along the way. He ran into Strahan in the Bahamas, for instance, on—what else?—a golf course. Strahan invited Miller over on his 34th birthday, and he used the time to quiz Strahan on the art they share.

“You want to be a legend on the field,” Miller says. “You want your career after football to be even bigger than [football] was, like him. We all aspire to be these guys. And I feel like I’m doing the research. It’s just the beginning.”

Early into his injury-surgery-rehab stretch, Miller discovered another unexpected positive. With little mobility, in Buffalo, in the winter, he was … happy. He expected his world might collapse a little, an inevitability simmering from what the injury had cost him. His world did not fall in, despite the setting, his age, the injury and all the other factors. “Beane took time out of his life to help me with my life. Went out of his way,” Miller says.

And, at that point, he knew. “This was where I needed to be and where I was supposed to be,” he says. “The best place for me is Buffalo.”

He jokes about his first game next season, against the Jets and his sometimes-workout-buddy, Aaron Rodgers. Oh, how perfect it would be to sack him, while healthy, Buffalo surging, on national TV. It took forever, Miller says, voice climbing, intensity ramped up, to understand what it took to win a Super Bowl, let alone win two, let alone plan on, as he jokes half-seriously, winning one for sure next season.

It's a lot. That’s him, extra before the term existed. But while Miller spins through the last year, the past five years and the past decade, tying all events together in the way only he can, he continues to return to that same word. Legacy has replaced dope, barely, as the favorite in his personal lexicon. His matters, and to him, more than ever before. Miller sees his impact spreading, widening, sharpening, just as he intended.

“All of that s---, man,” Miller says. “It’s more than just football. It’s really just everything.”