Thirteen Seconds: Patrick Mahomes, Chiefs Have Just Enough Time to Win Instant Classic

Randi Mahomes arrived at Arrowhead Stadium two hours before kickoff. She had a feeling she couldn’t quite explain. She was certain something would happen, something improbable and inevitable. A lifetime of watching her son play football—all the escapes, scampers, sidearm throws and late heroics—plus this adventurous Chiefs season, and a formidable opponent in the Bills, had informed an unmistakable vibe. But what? How? “I don’t know,” she said, before trying to summarize the feeling in one word.

Winning.

Randi wore bedazzled shoes and carried a bedazzled purse. Her son’s number was laid out with red-and-gold gems in three places, No. 15 splashed everywhere, all at once.

She stood on the carpeted steps of a suite inside the stadium, flanked by her mom, Debbie, and her daughter, Mia. All three spied the quarterback who connected them, Patrick Mahomes, alternately an NFL superstar, celebrity endorser and Super Bowl champion. But not to them. He chucked warm-up tosses on the field down below. None knew—not then—of the conversation their No. 15 had with teammate Mike Remmers earlier this week. It meant little, even nothing, at the time.

Somehow, the quarterback and the tackle landed on the topic of the Minneapolis Miracle, the nickname for an epic playoff triumph Remmers experienced while playing for the 2017 Vikings. Trailing, 24–23, the time remaining measured not in minutes but seconds, Minnesota quarterback Case Keenum threw up a desperation pass, which receiver Stefon Diggs snagged before his defender fell, before he sprinted into the end zone and NFL history—his score the first time an NFL postseason contest ended on a game-winning touchdown as time expired. Mahomes told Remmers he wanted that kind of moment. Indelible, etched in stone, never forgotten. No, the overtime touchdown he threw to tight end Travis Kelce to beat the Chargers in December didn’t count. He wanted that kind of moment at home, at Arrowhead, in the playoffs, with the highest of stakes, in front of a sell-out crowd and the woman who bedazzled his number on both her shoes.

Perhaps Mahomes felt a similar premonition. Perhaps not. Either way, a few hours later, he said, “I’ll remember this for the rest of my life.”

Pick a play. Any quarter, either team. Early on. Before halftime. Super late. In OT. Brimming with hope. Stiff-arming despair. After Nelly went on stage and rapped about heat in 40-degree weather and somehow managed to make sense.

It was hot in here.

Any play will do.

Or pick 17 plays, each from one fourth-quarter sequence by a Buffalo offense that trailed, 26–21, with just over nine minutes left. That’s as good a place to start as any. The drive started at the 25-yard line, as the Bills trudged slowly, deliberately and methodically up the field. They didn’t look like the less-experienced team in a game where experience is supposed to matter. Not with Josh Allen playing quarterback.

He didn’t move the offense so much as he willed it. As this particular drive stretched from five plays, to 10, to 15, Allen ran the ball six times. He converted a third down with a short pass to wideout Cole Beasley, converted another third down with a bull-rush up the middle and converted a third by pivoting around and streaking toward the left sideline. He did not convert his next third down. Which led to a fourth down, where Allen evaded Melvin Ingram III, juked two other defenders, confused another by faking a pass and ran for the first. Which led to both the two-minute warning and an obvious question: Not could Mahomes score if Buffalo took the lead? But would he have enough time? (Ha!) Which led to another fourth down, fourth-and-13 at the Chiefs’ 27-yard line.

As if Sunday night hadn’t been strange enough, a (perhaps, probably, likely drunken) fan sprinted onto the field. Perhaps this fan didn’t recognize Diggs, now with the Bills, from his Miracle days. But this fan won’t forget Jan. 23, 2022, either. Not after Diggs recorded an unofficial de-cleating, knocking an attention-seeker onto his backside.

Any play will do.

On the ensuing one, Allen drifted back, saw confusion in the Chiefs’ backfield and lasered a throw to a wide-open Gabriel Davis. The Arrowhead crowd gasped. Then, silence. It’s not that Davis is an unknown wideout; he caught 35 passes and gained 549 yards and six touchdowns this season. But Sunday, he caught eight passes, for 201 yards and an NFL-playoff-record four touchdowns. This game was drunk like that. Diggs snagged a two-point conversion on the next play, adding a key offensive play to his superb “defensive” one. Bills 29, Chiefs 26.

One minute and 54 seconds remained in regulation. It seemed fair to consider overtime at that point, or to wonder the converse of the previous question: Would Allen have enough time if the Chiefs kicked a field goal to tie it? But then Mahomes threw four passes, and three of them fell incomplete. The game clock ticked down to 1:16. “I always got faith,” wideout Tyreek Hill would say later. In that moment, he invoked Friday Night Lights—specifically, the character Boobie Miles, who, like Hill mimicked on the Chiefs’ sideline, liked to shout, “Feed Boobie, man!”

“I’m a dog, dawg!” Hill shouted.

The ball snapped, and Hill streaked like the intruding fan—only about 30 times faster—crossing the field from the left side to the right. Mahomes zipped a throw that Hill caught in stride, allowing the receiver to turn upfield without losing speed while determining the perfect path between defenders. Diggs wasn’t there to stop him. Hill found the one lane near the right sideline where nobody could catch him. “That’s just Pat, knowing exactly when I’m going to break,” Hill said. “Perfect timing. Perfect throw. Perfect play call. The rest is history.” Hill knew that before he scored, as evidenced by the peace sign he threw up with defenders nearby in pursuit. “Everything worked perfect,” he said, “just like it was supposed to.” Or had it?

Chiefs 33, Bills 29. Just over a minute left. Not nearly enough time for Buffalo to score a touchdown. Right?

Ha! This game was a time machine. The clock never ran out! Hours, half hours, minutes, seconds, didn’t matter. Never mattered. Any play will do. Allen went back to Davis (for 28) and back to Davis (for 12) and found Emmanuel Sanders for 16 more, just to break up the routine. Then, well, back to Gabriel catch-anything-and-everything Davis. He scored again. Bills 36, Chiefs 33.

The respective win probability charts looked like broken electrocardiogram machines, with lines everywhere, shooting upward, then plummeting, only to spike again. Coach Andy Reid wanted Mahomes to play “Grim Reaper,” and “go get it.” That’s what he told his quarterback on the sideline. Mahomes recalled Reid’s confidence, too. “We’re going to do this,” Reid told him. “We’re going to get in field goal range, and we’re going to get points.”

Delusional! All of them! Only 13 seconds remained in regulation, which is hardly enough time to run a play, let alone direct an offense halfway down the field, far enough for a kicker with a strong leg but two misses Sunday—one field goal, one extra point—to make an attempt with all the pressure of the moment landing squarely on his shoulders.

In her suite, with her family, Randi continued trying to “speak [an ending] into existence.” She said things like “he has enough time” and “he better not run” as her son, No. 15, jogged back onto the field.

It’s funny, because it’s true. Moms know, right? They possess that Spidey sense of intuition. Like Donna Kelce, who sat in a hotel lobby near Arrowhead on Saturday afternoon and sipped from a coffee cup as she nonchalantly and inadvertently predicted the seesaw nature of a playoff game that would kick off in 26 hours. “You just never know,” she said. “It’s always in the back of your mind. Anything can happen.”

She understood that, because both her boys—Eagles center Jason and Chiefs tight end Travis—made the NFL, became starters, then stars; they won Super Bowls, overcame injuries and, eventually, came to play for separate teams on the same Sunday in the same playoffs. Because Donna believed that anything could happen, she decided to make a daring attempt at attending both of their games in person.

On the afternoon of Jan. 15, she drove from her home in Orlando to Tampa, because the Eagles kicked off first, against the Bucs, at 1 p.m. the next afternoon. She stopped at the airport but not to fly—not yet. Instead, she checked into a hotel there, stayed the night and took a cab over to Raymond James Stadium, leaving her bags at the front desk.

With the Bucs in command—and Jason’s season pretty much over—she left near the end of the third quarter, only to realize that the Uber lot was a long hike away. Fortunately, a pedicab happened to roll by, and when the driver asked why she was leaving early, she explained: two games, two sons, her trip. He pedaled faster, as if entering a Tour de Tampa, and when she arrived at the ride-share lot to find no rides, he helped her hail a taxi, then directed traffic until a path forward opened. Hotel. Bag. Airport. Then … a delay!

She changed jerseys, swapping Eagles for Chiefs, and chatted with strangers who were, by that point, following her sojourn on social media. Her flight sat on the tarmac for another 30 minutes. Upon landing, fellow passengers told her that Travis had already scored a touchdown. The game was close. The Chiefs had arranged for a driver, who picked her up and promised to care for her luggage. But the volume of text messages overwhelmed her phone, which kept freezing, meaning she couldn’t open the app with her tickets. A team official came to the rescue, and she settled into her seats—whew—as an offensive avalanche started. Mahomes threw five touchdowns in under 12 minutes of game time. Her son would also throw the first touchdown of his life, a bucket-list achievement he had long ago predicted. She would surprise him in the postgame interview. And Donna would arrive this past Saturday after a much easier itinerary believing that anything could happen, because the weekend before, anything and everything already had.

She would also issue another clarification that would seem prescient the next evening. “It seems like it’s effortless,” she said of the Chiefs’ run, the three straight AFC title games that Kansas City hosted, the back-to-back Super Bowl appearances, all the points scored and the triumph in LIV. But effortless? “No,” she said. “It’s not.” After all, the Chiefs had lost that first conference championship game to the Patriots, in overtime, when her son, Mahomes and the Kansas City offense never even touched the ball.

Donna Kelce settled into another suite Sunday afternoon, as the Rams—anything can happen!—upended the Bucs in Tampa. The sun set. The stands filled. Fireworks exploded overhead, as the Chiefs’ offense sprinted onto the field, one by one, for introductions. Travis went second-to-last, smoke billowing. Mahomes followed him, fists pumping.

The real fireworks would go off soon enough.

First drive: Allen converted an easy fourth down at midfield, exhibiting an ideal formula of patience mixed with interludes of spectacular. The Bills scored, right away, and watched as Chiefs safety Tyrann Mathieu—the heartbeat of the Kansas City defense—entered concussion protocol, never to return.

Mahomes still answered, like on third-and-5 at his 31-yard line. He scrambled away from pressure, moving left, then forward, then right, then, somehow, flipping the football forward but in the opposite direction as his momentum carried his body—for a mind-boggling completion.

The Chiefs had figured the Bills would run a lot of Cover 2 shell, a zone coverage designed to limit big plays. That very scheme had slowed Kansas City down midway through the season, made the Chiefs look—relative to their own standards—mortal, human. Buffalo did just that, playing a ton of zone but mixing its coverages, and Mahomes countered by running with the ball, much to his mom’s chagrin. On the first drive alone, he gained 49 rushing yards and scored a touchdown with his legs.

Already, the crowd had to react as if watching a tennis match, heads flinging back and forth, as two high-powered offenses streaked down the field. Anything did happen. Any play did do.

Early, second quarter: Buffalo punted for the first time this postseason. Based on the Bills’ bludgeoning of the Patriots, this qualified as newsworthy.

Later, second quarter: On third-and-goal, Mahomes continued with his magic routine, running left, turning 180 degrees and starting to dash right, only to see a defender closing in from only a few yards away. Mahomes made a split-second decision in that instant, lofting a ball toward the end zone, the arc perfect, the flight path sublime. The defender nailed Mahomes and he lobbed this particular attempt off his back foot, toward Byron Pringle. As the quarterback fell, two other defenders dived toward his intended target. Too late. Touchdown. The Chiefs took a 14–7 lead, and, for proof of just how much happened afterward, this throw—impossible, not to be attempted and so very Mahomes—was all but forgotten in the aftermath.

Even later, second quarter: Just when the Chiefs seemed to have seized momentum, there came Allen, with another drive. With 42 seconds left, he noticed that Kansas City planned to send extra blitzers, with seven rushers total, and he motioned Beasley over near Davis. The wideouts ran a nifty switch-release, leading their defenders to Keystone Cops–fall into each other, with Mathieu out. Touchdown, Davis. Naturally. Any play will do.

On and on this went, as millions of fans drooled over an offensive display unlike almost any in NFL postseason history. It would be hard to find a game with a comparable mix of plays, stars and stakes. Mahomes ducked down to create a sidearm angle on one pass to Hill, slinging a dart not over a defender’s outstretched arms but under them for a completion. He would never stop moving, running this way, then that one, sprinting forward or backpedaling, scampering, pirouetting, juking, faking, sliding, even bouncing up after a defender’s knee collided with his head.

As the Bills shifted their attention—and defensive emphasis—to how and where Mahomes moved, the rest of the Chiefs’ offense opened up. But fold? No. Not these Bills.

Late, third quarter: With Kansas City up, 23–14, Allen decided to show off perhaps pro football’s strongest arm. He dropped back, stepped forward and launched. His pass traveled roughly 60 yards in the air, leading to audible gasps, as Davis beat his defender and settled under it. Another touchdown; this time, in a drive that lasted for all of 10 seconds.

For a while, it seemed like the Chiefs were making the most critical mistakes. Their kicker, Harrison Butker, missed a field goal before halftime and an extra point in the third quarter. Then Reid and his offensive coordinator, Eric Bieniemy, made what appeared to be the most critical (bad) decision of all.

Early-ish, fourth-quarter: After a penalty negated a Bills punt, forcing a second, redo attempt, Hill caught the ball as it descended and streaked up the right sideline for a 45-yard return. “Rookie-year me? I probably would have cribbed that,” Hill said, meaning he would have scored. “Come on 10!”

And yet, despite starting the ensuing drive only 16 yards from the end zone, the Chiefs sputtered. On third-and-1, neither Hill nor Kelce trotted onto the field. The anything that was happening for Donna Kelce was her son having a smaller impact than usual. Mahomes didn’t take the snap, either. Instead, it went to a backup tight end, Blake Bell, who handed the ball off on a play that lost three yards. Butker made a field goal, which set up the Bills’ long drive, the late swings and the 13 seconds that remained in the Chiefs’ season.

Afterward, no one could believe it. Not the coaches, not the players, not the fans—and not the moms.

“I’m just sorting it out,” Reid said.

“I’m catching a cramp right now, as we speak,” Hill said. “Oh … God … ouch. Can I get some water?”

Only Mahomes seemed unruffled. “It wasn’t hard to keep them focused,” he said. “We believed.”

But 13 seconds? Seriously? Come on!

Really late, fourth quarter: Mahomes found Hill for 19 yards. Eight seconds remained. He dropped back, scanned the field and there was—who else?—Kelce, exactly where Mahomes wanted him. Pass, on target; range, found; Butker, good. Tie game. Overtime.

Anything can happen.

“If you’re not going to go down fighting, then you don’t deserve to be here,” Mahomes said.

This wasn’t the conference championship game from four seasons ago, the one where Tom Brady led the Patriots down the very same field to push back the coronation of Mahomes. This time, the Chiefs won the coin toss before OT. This time, Mahomes led an offense down the field, as a worthy challenger to his kingdom stood on the opposite sideline, shield ready, sword sharpened, but never to jog back in.

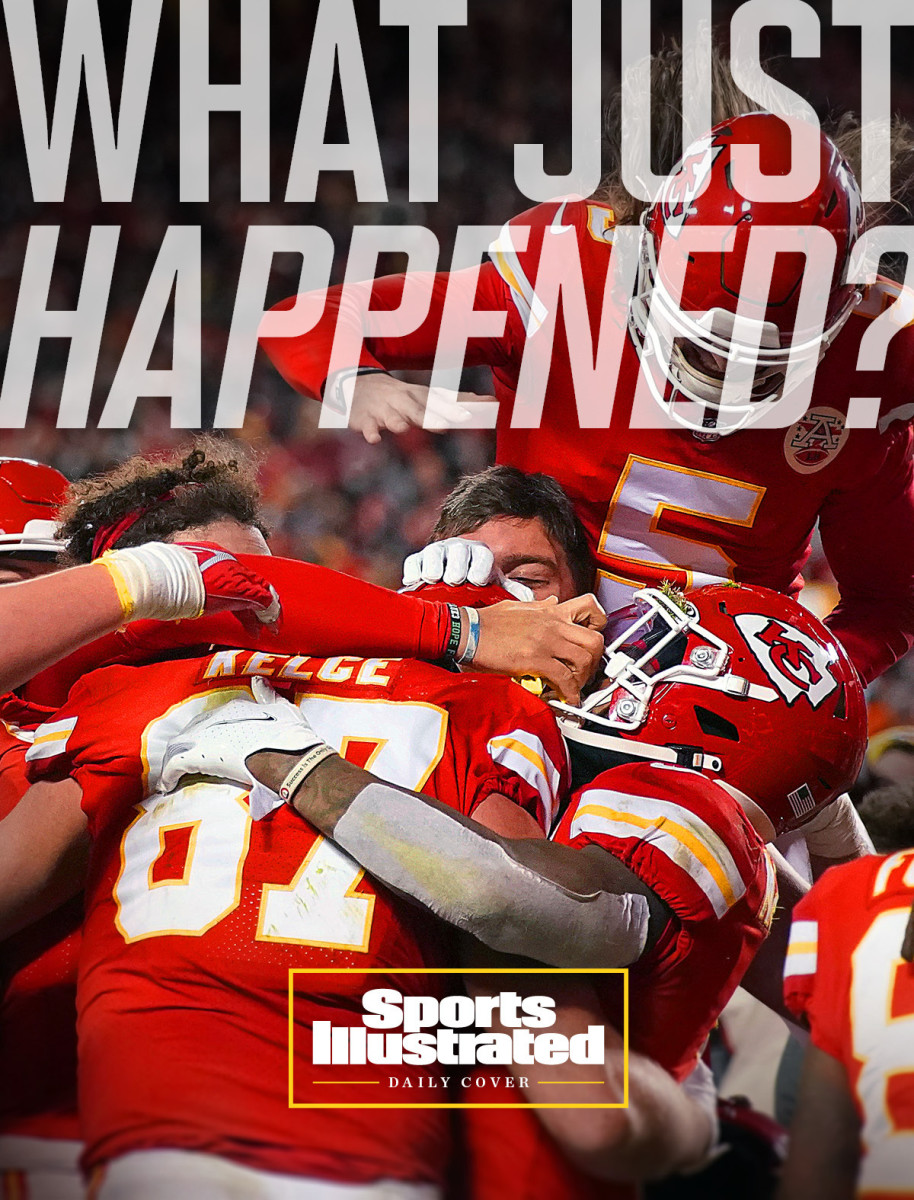

Overtime: Mahomes dropped back, passing for the 44th time. He would say that Kelce “wasn’t necessarily supposed to do [what he did], but we got a look at what the defense was doing.” Mahomes threw. Kelce turned. Ball met hands. Feet met ground. Kelce was already certain; he was inbounds and in control. Mahomes ran over and jumped on top of him, yelling “I love you, man” and things like that.

One of the greatest playoff games in NFL history had ended, ensuring the Chiefs will host their fourth straight conference title game. “Those are two of the only players on Earth who can make those plays,” Mahomes said later, meaning Hill and Kelce. He also could have been talking about himself and Allen, two quarterbacks now firmly entrenched in an NFL rivalry, the kind that can define not seasons but eras. This isn’t any sort of dawn. More like high noon. “This is definitely another step for him into the Hall of Fame,” Hill said of his quarterback.

The Chiefs celebrated like children in the locker room, piling on top of each other, screaming and yelling. Their triumph wasn’t exactly the same as the Super Bowl, but it was pretty darn close. As they embarked on a well-earned celebration, perhaps they would have been wise to listen to their mothers. Because anything can happen, sometimes a million anythings—and on an epic night to cap off an epic NFL playoff weekend, sometimes winning, however it happens, however far away it seems, is the delightful result.

• Cooper Kupp's Approach to Greatness

• Arts and Crafts, Belichick-Style

• Mac Jones: Reassessing the 2021 Draft’s Most Polarizing Player

• A Quarterback Evolution and a Coaching Revolution

• The German Import Helping Define the Post–Tom Brady Patriots