Film Breakdown: Jordyn Brooks Set to Dominate Run Game with Seahawks

This is the third article in a five-part Jordyn Brooks film breakdown:

- Part 1: Evaluating Seahawks LB Jordyn Brooks' Coverage Skills

- Part 2: Jordyn Brooks Adds Weapon to Seahawks Blitzing Arsenal

- Part 3: Jordyn Brooks Brings Run Dominance to Seahawks

- Part 4: Seahawks LB Jordyn Brooks Has Elite Fundamentals

- Part 5: Did Seahawks Reach Selecting LB Jordyn Brooks at No. 27 Overall?

Jordyn Brooks accounted for 26 percent of his defense's tackles according to Seahawks general manager John Schneider. Indeed, Brooks' play versus the run is an endless highlight reel. This is still important in 2020.

It is fair to question the value of players who stop the run in the modern National Football League. Yet you only have to look at Seattle’s division to understand that run fits do matter. I’m fully aware they aren’t exactly fashionable. However, this is my attempt to make them sexy. Please.

The NFC West has offenses that are designed and layered off run action. Sure, we have no analytical evidence of correlation between run rate and play action effectiveness. We also lack statistical proof of run success impacting the success of play action.

But whether it is the 11 personnel, outside zone-driven Los Angeles Rams, the 21 personnel, diverse San Francisco 49ers, or the scrambling threat of Kyler Murray quarterbacking the Arizona Cardinals, being able to slow the core movements of these attacks does matter. The counters and sucker big plays come off similar-looking action. Oh, and the Seahawks’ stopping of the run - like the rest of their defense - stunk last year. Sports Info Solutions’ data logged their 2019 run defense as 26th in success rate and 26th in DVOA.

Brooks’ tape can be sorted into plays that translate to different Seattle run fit responsibilities. Playing for two Texas Tech programs means Brooks has experience in a variety of run fits, as was the case with his different pass coverage opportunities.

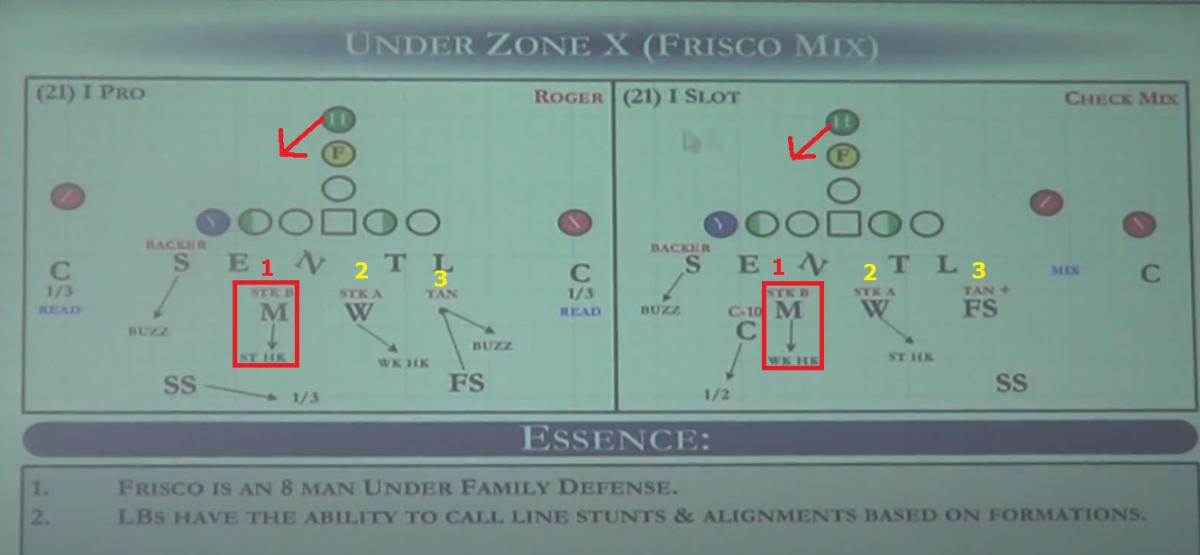

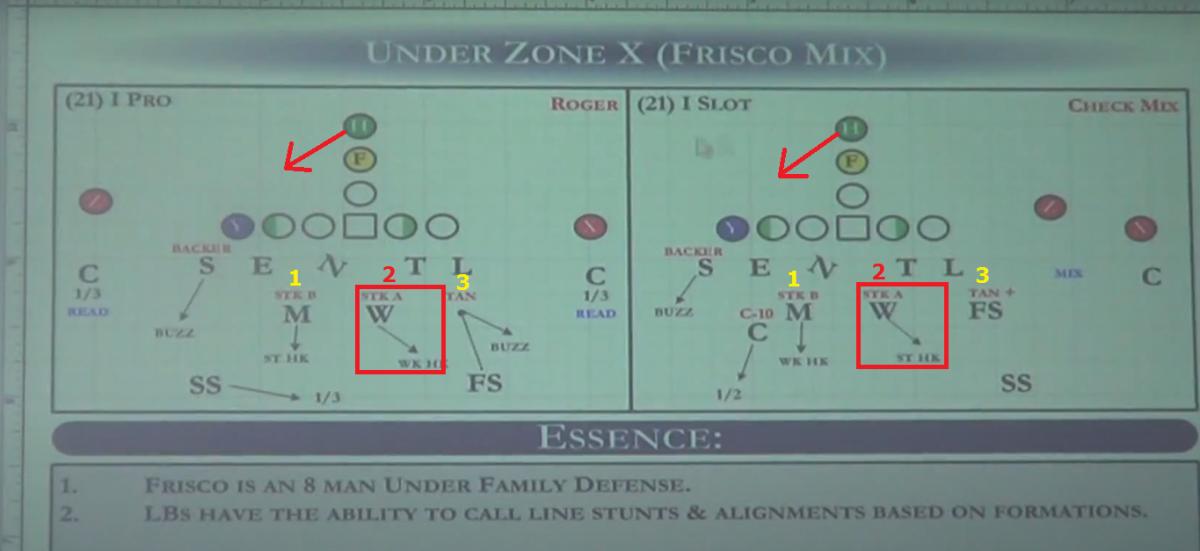

Regarding the 2019 scheme in particular, there isn’t much of a difference in what the Seahawks ask of their linebackers versus the run and what Matt Wells’ staff did. After all, Carroll has his roots in middle of the field open, 4-3 structure.

Run Fits

Talking about the first defense of his college career, Brooks revealed that the middle linebacker role he played was a misleading title.

“I played outside linebacker my first three years, at Tech, pretty much,” he told reporters after being drafted.

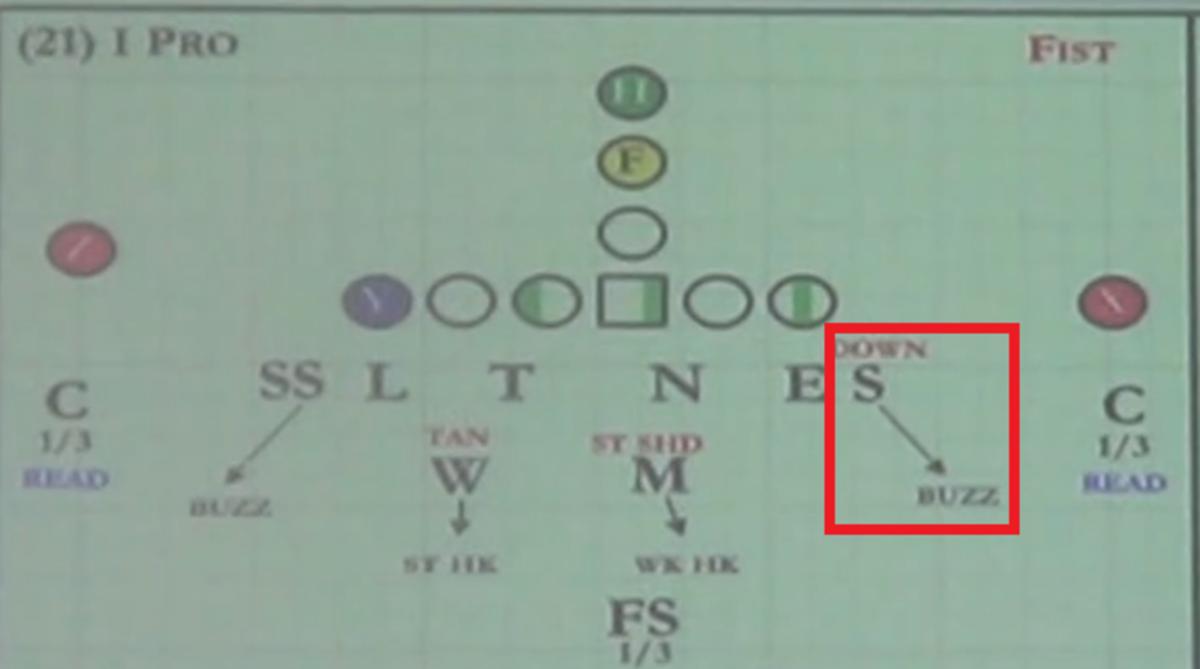

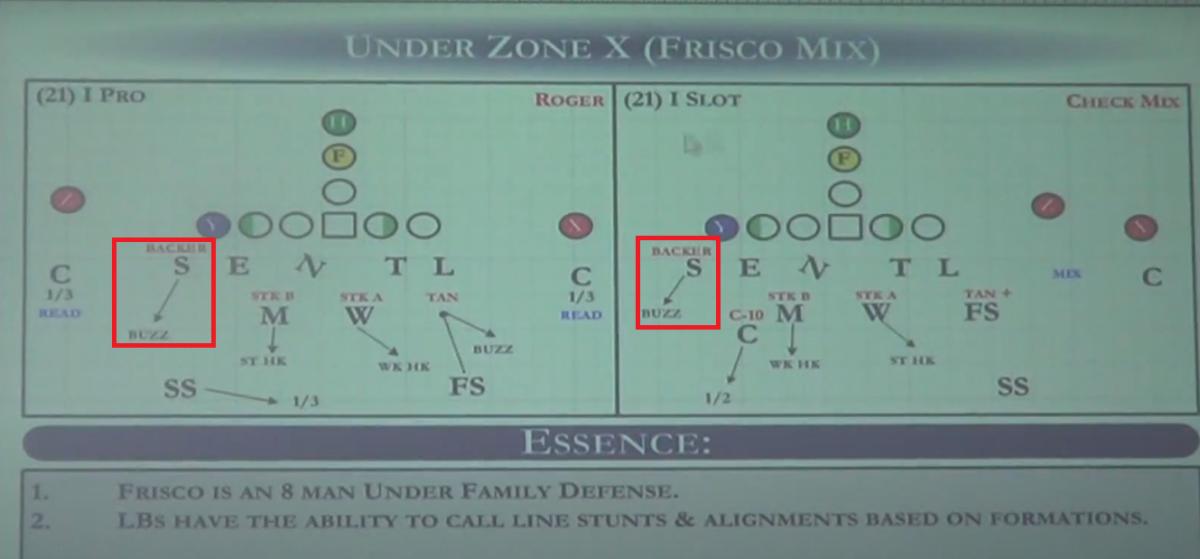

This placed Brooks out in space, on the perimeter of the defense. The Seahawks’ equivalent would be the SAM linebacker role and the ‘hammer in the fit’. The SAM linebacker in Seattle’s run defense is a pure edge setter who must play aggressive. They have one job: force the ball carrier inside or, if the runner is determined to go further outside, force a significantly altered path. This is why the Seahawks’ SAM is often aligned down at the line of scrimmage.

Brooks plays with the aggression required to do this at a high level. He shows up in the fit fast and willingly smacks blockers back. It is Thanos-like destruction that helps the rest of the defense. The fierce edge was particularly noticeable against the pulling of guard-tackle-wrap/counter.

Brooks’ footwork sets up the optimal path for taking blockers on. He mostly uses his near-shoulder to block-destruct, meaning that his outside arm is free to make the tackle if the runner attempts to bounce further outside - this is the style Seattle teaches too. Brooks was able to disengage from his block-butchering to make tackles himself, coming loose when needed.

Offenses look to target an outside linebacker placed down at the line of scrimmage by throwing it quick outside, yet Brooks has the range to get from a cover-down position and meet throws to the perimeter.

Before looking at the rest of Brooks’ run fit assignments, we must recognize the context of his college situation. Texas Tech was a middle of the field open coverage team throughout Brooks’ time there. Their insistence on running variants of Cover 2 and Cover 4, with two-high safeties, meant they were regularly out-gapped against the run.

What does out-gapped mean? It’s when a team has fewer defenders in the box run fit than the offense has gaps. A gap can be created by a blocker or the quarterback read. Middle of the field closed teams have an extra man in the box, as they have just one high safety, meaning they are "gapped-out." This is why the NFL is predominantly has MOFC defenses. Seattle, known for its Cover 3, is included in this, running one-high defense 64 percent of the time in 2019 according to Sports Info Solutions.

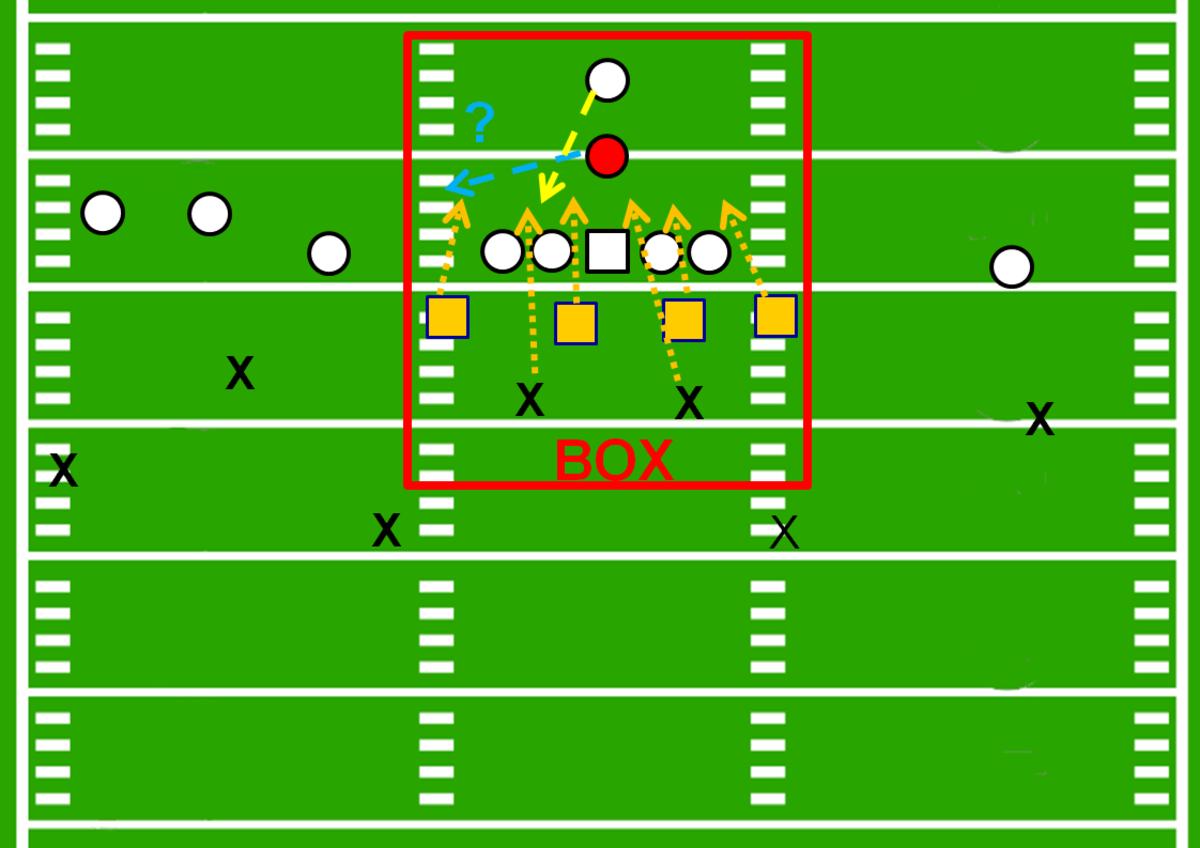

The challenge of being out-gapped forces MOFO teams to get more creative when fitting the run. Stunting defensive linemen to win gaps back, buy time, and spill the football to waiting second level defenders is one approach. Or you can do what the Red Raiders did, which is relying on a superstar to essentially two-gap, filling so many holes and making plays. That superstar was - you guessed it - Jordyn Brooks.

After drafting Brooks, Pete Carroll summed Texas Tech’s scheme up nicely, saying, “They entrusted in him to be the playmaker, kinda cover up for everybody."

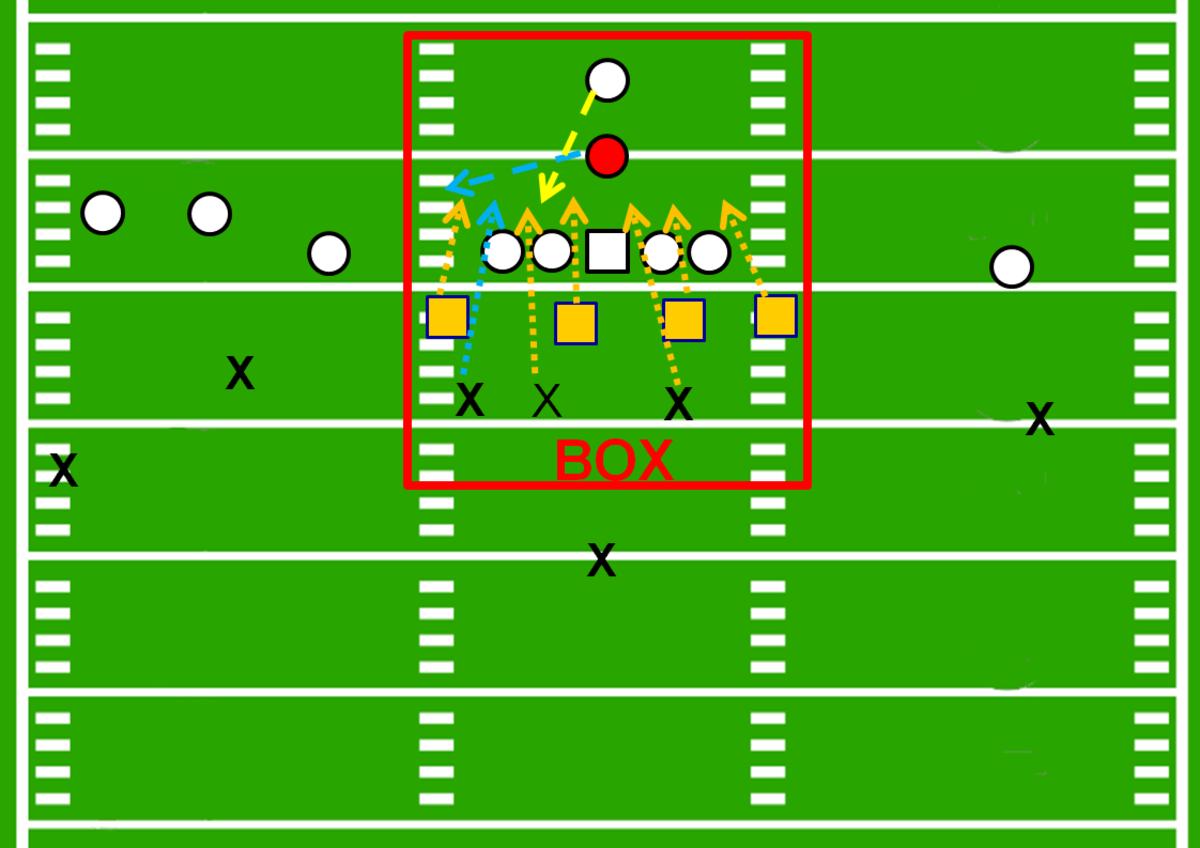

In both the 2016-2018 defense and the 2019 system, Brooks mainly had three defensive lineman in front of him. Variations of the Tite front were commonplace from the Red Raiders. By having a 4i-0-4i alignment (inside shoulder of the tackle-heads up-inside shoulder of the tackle), the defense pushes the out-gapped issue to the perimeter, denying the opposition an interior bubble. Team speed then can rally outside to the football.

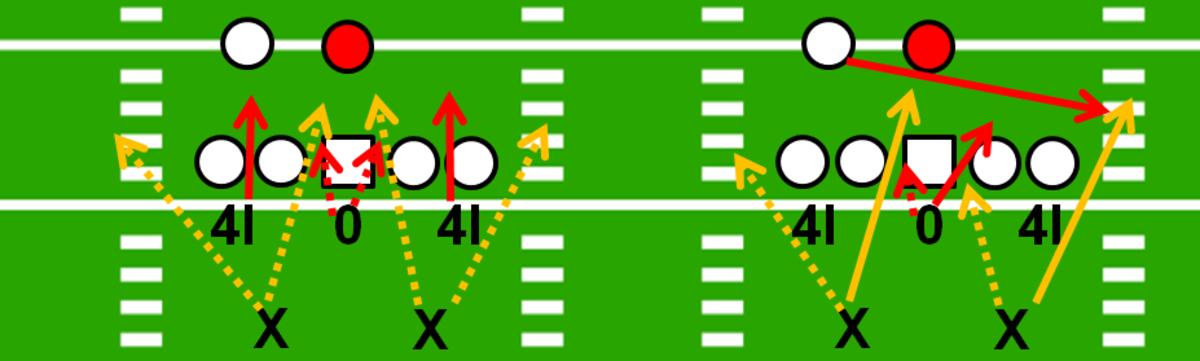

The two linebackers behind the three DL read the flow of the run, one fitting the play-side A-Gap and the other fitting the play-side C-Gap.

In addition to this 3-2/3-4 look, Texas Tech ran versions of a 3-3 stack. With an additional linebacker in the box fit, the trio were able to "lever, spill, lever" the ball similarly to Seattle. In both the 3-2 and 3-3, the linebackers are on a string together. This is conceptually similar to how the Seahawks’ second level fits the run.

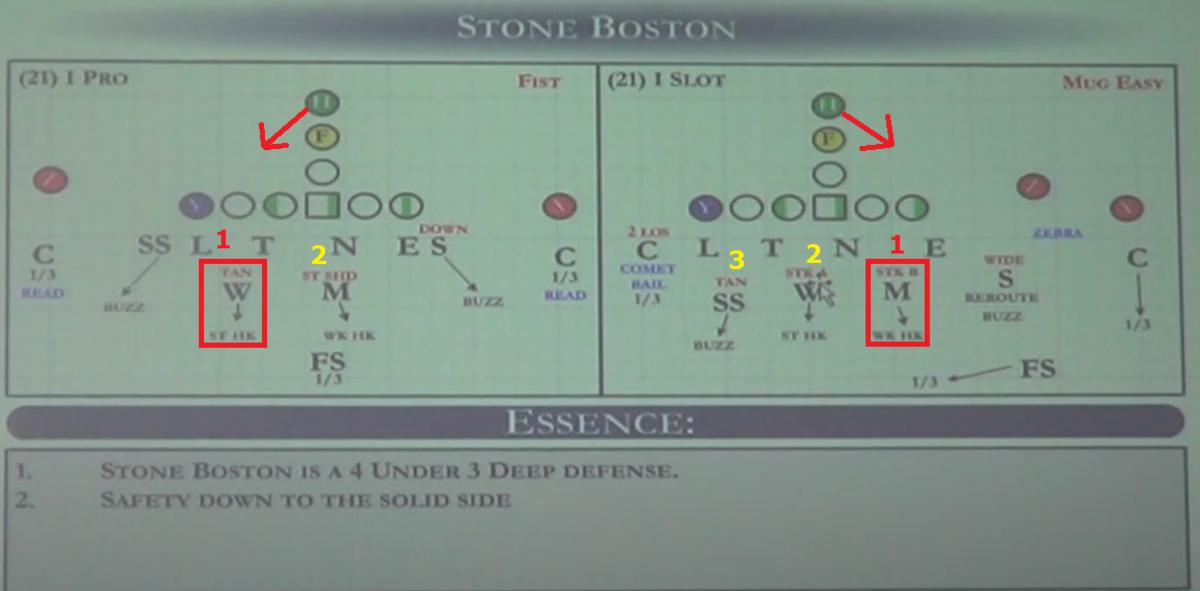

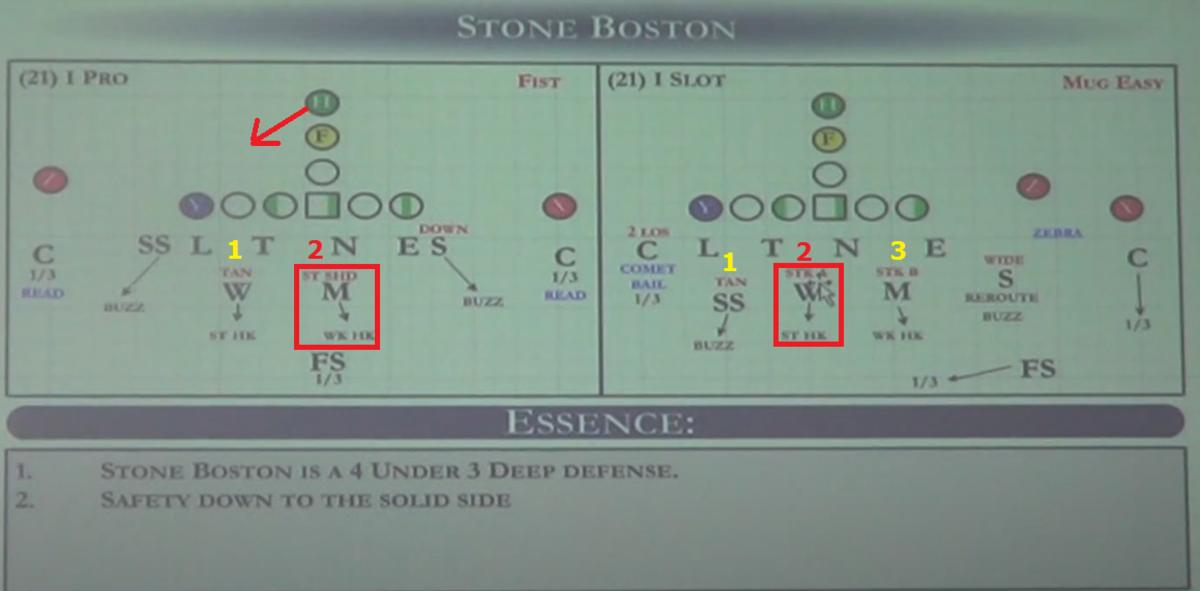

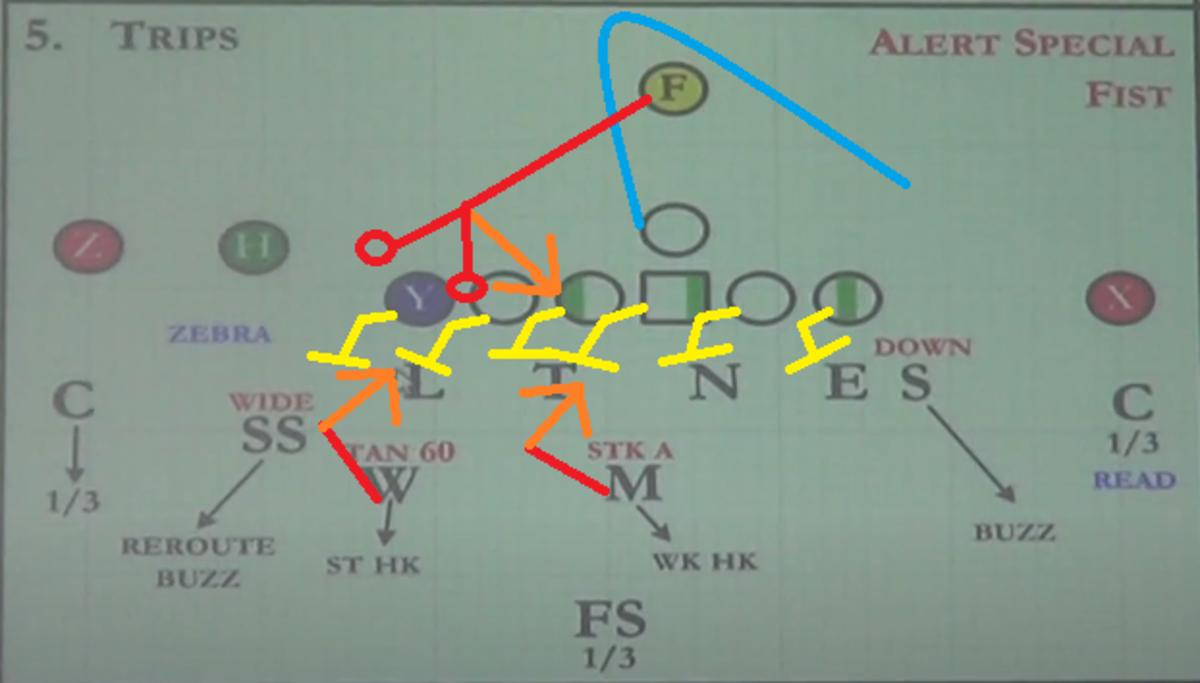

Inside of Seattle’s hammer/force defender is the 1 in the fit, the "turnback" player. This "TAN" or "Stack B" assignment predominantly fits outside-in on the football and must lever the ball carrier back inside to help arriving from the other second level players.

Any block the 1 in the fit faces must see them flow outside to turn it back, going over the top. Sometimes they’ll be responsible for the B-Gap in stack fits; other plays they’ll be the spare man in "slide." This task can fall to the MIKE or the WILL linebacker. It depends on what front the Seahawks are in and what formation they face.

Brooks’ sense for where the ball is and quick recognition of what run he is getting saw him move down and outside quickly to stone blocks. His turnback play’s physicality was complimented by his ability to disengage when required. One thing Brooks could do better is use his hands more regularly as opposed to his shoulder or slips. (I’ll cover his block techniques in more detail in Part 4)

Seattle’s run defense wants to have a TAN/turnback/lever player to each side of the formation. If the run goes away from a turnback player, rather than being 1 in the fit, they become 3. Their assignment on the backside of runs is to pursue to the next available gap, moving to the ball and filling in where required - a backside lever. Like with the turnback player on the front-side of runs, both the MIKE and WILL can become the next available player in the run fit depending on the front called and formation encountered.

Brooks again keys run-type rapidly when playing in this next available look. He leverages the ball and presses the line of scrimmage superbly, staying patient while sifting along to make tackles. His pursuit being downhill in addition to lateral places pressure on the ball carrier, removing cutback lanes and pushing the ball wider. Brooks truly fits each next available gap, eliminating possibilities until he finds the football.

Having covered the hammer and the #1/#3 in Seattle’s run fit, we now arrive at the 2. The 2 plays more inside-out on the football, getting inside of pulls and spilling certain blocks with their inside shoulder to teammates outside. They can be tasked with stacking the A-Gap, run through on the play, or Strong Shade, "fast-flow" to the football. This can either be the MIKE or the WILL - again, front-type and opposing formation dictate the responsibility.

Brooks’ senior season gave him the most run through and fast flow opportunities, as he spent more time in a true MIKE linebacker role.

“I think they tried to highlight him in this past regime,” reviewed Carroll. “In that they put him in the middle of the defense, he really had a chance to really flow and run to the football.”

Brooks’ ability to trim the fat off blockers like a top carver meant that his tight, aggressive paths were often too extreme for opponents to handle. He could hide from blockers to avoid contact, he could power through blockers with violence, and he regularly won when attacking inside-out. A-Gaps were his route to a profitable habitat behind enemy lines. The backfield was his hunting ground.

Screaming clean through to the running back through inside gaps is scheme-altering. Brooks understands blocking schemes and he can punish them; his 20 tackles for loss last year is testament to this. Brooks knows when he can shoot his gun - for example, doubling the nose tackle allows him to go.

Once fired, Brooks is able to adjust his pursuit angle at high speed, meaning that he can really mess up outside zone for tackles for loss. Like with other elements of his game, Brooks defies what is typical in football: he isn’t supposed to make these plays. Seeing this against the Rams will be fun.

Most Big 12 offenses were left trying to get two blockers on Brooks, because he’d beat the first one when running through. This was especially noticeable against gap-blocked, power runs. Brooks would beat the down-block designed for him and then spill the puller while being big in his gap.

Brooks being a two-for-the-price-of-one, run through fitter, will sure be useful. In 2019, the 49ers were a 34.5 percent man-blocked rushing team per Sports Info Solutions. Meanwhile, the Cardinals gave the Seahawks problems with their gap-blocked, Guard-H Back Wrap/Counter last season.

Brooks’ play against the run and ability to take out two blocks could be overlooked due to the combination of Texas Tech being out-gapped and also out-talented. Watch and listen to the breakdown below for the perfect illustration:

Turn sound on to hear me explain this Jordyn Brooks play. This is exactly the kind of stuff the Seahawks ask of their "Mike", running through and spilling to the outside:pic.twitter.com/THHaPpdwqM

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) May 17, 2020

Similar to his scraping to the next available gap, Brooks is able to aggressively press his gap before fast-flowing outside to runs going outside of his initial assignment. His excellence at playing off the butts of his teammates is prevalent. Brooks first stays in his inside gap, then processes the trash quickly and keeps offensive linemen off him before getting to the tackle. Brooks’ control and patience as a fast-flower puts him in the ideal situation to make these plays.

Brooks’ ability to understand what run type he is getting and find the football speaks to his excellent recognition from the linebacker spot. It enables him to fulfill his run fit successfully and as quick as possible. Lots of coaching of the position talks about using a triangle key for identification, reading from the guard to the running back to the football.

Where the eyes are looking is crucial. The Seahawks themselves speak about "lever keys," which are integral to how quickly their linebacker responds to the run fit. These are players who shape how each defender needs to fit and adapt their leverage. A fullback is one lever key. So is a tight end. Another is offensive guards.

It’s on gap runs where Brooks’ guard, h-back, tailback keying is most obvious. He reads his triangle and identifies guard-pull in record time. The offense can try to get more numbers to the play side, but Brooks will match this and find the ball, slipping down-blocks on the way. Counter, dart, guard-tackle-wrap? Lever or spill? Turnback or run through? Brooks gets it done.

The challenge of playing in an out-gapped defense was something that Brooks was able to overcome to the point of thriving in the situation. This was thanks to accomplished "stack, track, fallback" play.

The technique was most noticeable against gun zone runs. With the 4i in front of him flowing into the B-Gap versus zone, Brooks would have to flow that way too, stacking his interior gap, but staying ready to fallback to a different gap.

It was quasi two-gapping which Brooks took to a new level, hiding from blockers before popping back to make the stop.

A difficult example of this is playing on the back side of zone read. Brooks would be placed in a 30 tech in the B-Gap. He’d have to stack the A-Gap versus inside zone, tracking the ball. However, Brooks also needed to wait to clear the quarterback keeper to his C-Gap. If the quarterback did have the football, Brooks would have to fallback to this for the tackle.

You’ll notice Brooks dominating zone runs often featured the linebacker making tackles on running backs cutting their run back. This is super relevant to the Seahawks. Teams run zone for the cutback and NFL teams block zone in a way that requires stack, track, fallback technique. With Seattle coaching their linebackers to go over the top of blocks, the way to make the tackle versus zone is by using this technique, especially versus shotgun sets.

Remembering that the Seahawks do run middle of the field open stuff where this applies, against spread looks from 11 personnel the middle of the field closed defense needs to stack, track, fallback too.

Trips is a great example, where the overhang to the three receivers is out of the box fit. Even with their "one-back, one-gap" rules, the linebackers have to stack, track the zone blocking action before falling back with the cutback.

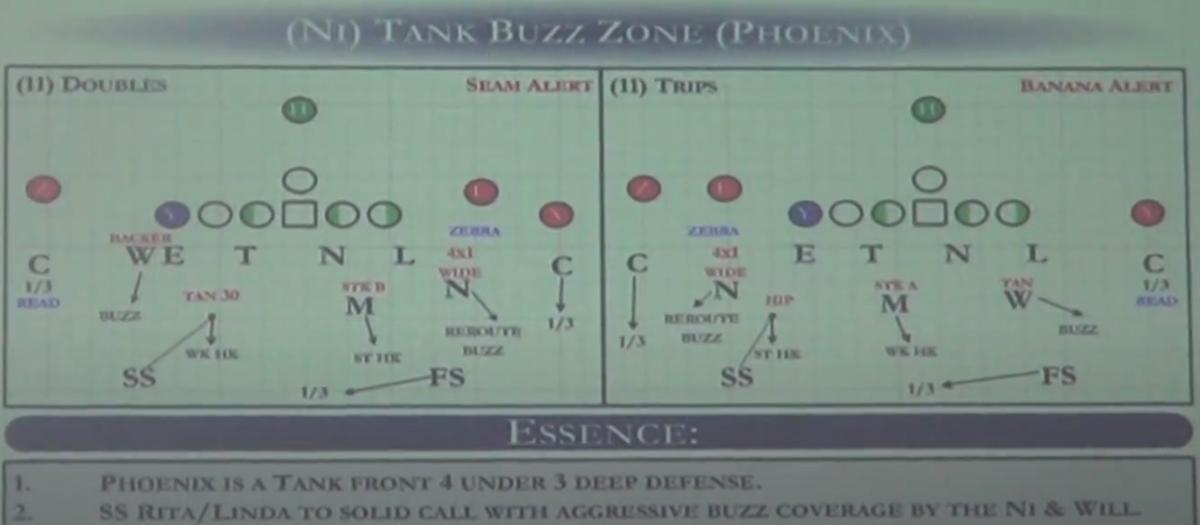

On the subject of "Tank" fronts and falling back, parts of Brooks’ 2019 season put him in a better situation to cope with how Seattle does things up front. The Baylor game in particular was notable because Brooks played behind a four-down structure that used a heavy 3-technique and a 2i nose tackle.

In that game, Brooks showed an ability to play off each defensive tackle, falling back off the heavy 3-tech and belly-keying to double-gap the A-Gaps with the 2i. The Seahawks love using heavy techniques to buy their players more time in coverage and keep them clean. It requires this goodness. Check my early off-season article for more on Seattle’s heavy techs.

Seattle allows their defensive ends to make plays if they can, for instance dipping inside from their initially assigned run fit for easy penetration. As K.J. Wright said in his NFL Game Pass film breakdown, it’s then up to the linebackers behind to “make your d-lineman right.” (6:42 timestamp) The linebacker has to play off the end.

In the Tite front or as a 00 tech stacked behind a heads-up nose tackle, Brooks played off the ‘lag’ or ‘push’ techniques of the nose tackle. Additionally, the 4i occasionally dipped back outside to the C-Gap when reading the run. Brooks read this and adapted accordingly. In short: Brooks is able to make his defensive linemen right.

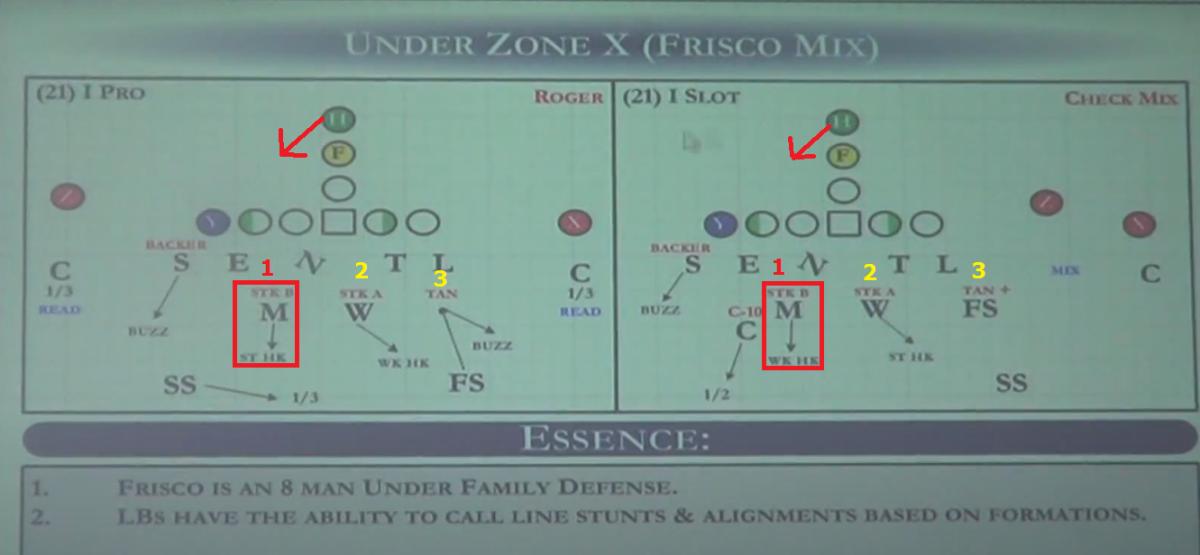

One thing that Brooks’ college career didn’t allow for was playing off four-down stunts. Carroll, on the other hand, will stunt his defensive front and also move his line on fire zone blitzes. It requires the linebackers behind to fallback with the movement. Take Pirate, run from an over front, where the end and 3-technique slant a gap over.

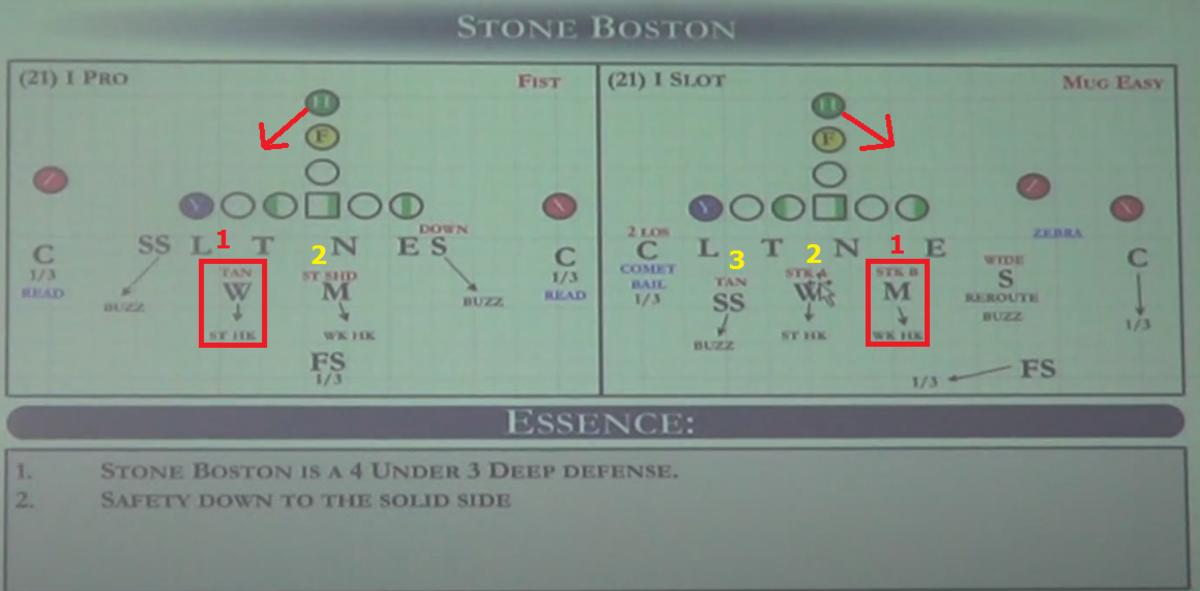

Pirate is something Pete Carroll has applied to his Cover 3, run out of his "Boston" (Over) front.

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) June 3, 2019

It always comes from the 3 tech side, was an automatic against Far formations.

2014. Rams running bend. Seattle got dudes playside and fallback linebackers were free to tackle. https://t.co/2RPcK6zdXU pic.twitter.com/idd7f0jN0R

While not used to things like Pirate, Brooks has all of the traits to be fine with it. His patience and understanding of where the ball is going should make this an easy learning process.

What’s most exciting about Brooks’ career in Seattle is that seeing him play in a defense that is gapped-out most of the time will give him the opportunity to make even more plays. Offenses won’t be able to send two blockers at him as often. SAM, MIKE, or WILL, Brooks can fit the run well from each spot.

Brooks can further lower the efficiency of the inefficient run and this is obviously a positive. Moreover, having a player who slows the first part of the action leaves the defense better equipped to halt the deception that arrives from similar looks.

Where defenses encounter difficulties is when they are left playing catch up to one or more of the plays in the run-action sequence. Brooks’ diagnosis skills and run fit brilliance puts him in an excellent position to handle the vertical and horizontal stress that is inflicted by NFC West attacks. He has the coverage traits you’d want too. (see Part 1)

The question Brooks will have to answer in Seattle’s run defense is whether he can adapt to being lied to via play action and run-pass options (RPOs). At Texas Tech, Brooks could trigger fast against the run because he often didn’t have much pass responsibility. He wasn’t wrong, but was largely able to stay playing downhill - for instance attacking the quarterback keeper on play action bootleg rather than having to bail back into coverage.

How deceptive play-fakes impact Brooks’ fitting of the run will be part of his learning process, where playing with doubt equals death. The solution will likely be as simple as learning Seattle’s keys and studying film.

Brooks sure seems smart enough to cope. After looking at his core football fundamentals in Part 4, I’ll finish with Part 5 and an analysis of his fit among Seattle’s existing personnel, with a discussion on best player available versus need