How Clint Hurtt’s 3-4 Seahawks Defense Can Lean on Pete Carroll’s 'Stick' Experience, Part 1

This is part one of "How Clint Hurtt’s 3-4 Seahawks Defense Can Lean on Pete Carroll’s 'Stick' Experience." In part two, Matty F. Brown looks at how Carroll and Hurtt's college experiences helped shape their 3-4 and bear front usage in Seattle.

Seahawks defensive coordinator Clint Hurtt quickly made his love of 3-4 defensive systems obvious in his revealing media cycle. With Pete Carroll’s squad thought of as a 4-3 defense, the promise of change is understandably exciting. It’s fun to get swept up in the shiny new thing—to get hopelessly lost in trendy innovation.

Carroll, however, has been coaching defense since 1973 and has more experience than he may have let on in the 3-4 sphere. Football scheme is cyclical and this will only help the Seahawks in their transition with Hurtt.

“When I came to Seattle, obviously we were back more in the 4-3 world, but there were still—they would never say it—there were still some 3-4 elements to the stuff in base defense,” Hurtt told reporters on February 16. “With Pete, I would say it and he would look at me like with a sneer, and I’m like: "‘Well, it’s okay [laughing]. I see what I see.’”

Hurtt may well have misinterpreted Carroll’s sneer, or it’s possible the 70-year old coach was back to his prankster ways; what's certain is the new defensive coordinator was seeing the right things. Carroll’s system of defense has always featured 3-4 elements—something the head coach has said in the past.

"Our defense is a 4-3 scheme with 3-4 personnel,” Carroll described back in May 2012, when the Seahawks were planning on running a lot of 4-3 under fronts with Red Bryant as their big end, Chris Clemons as their LEO and K.J. Wright at SAM linebacker. “It’s just utilizing the special talents of our guys."

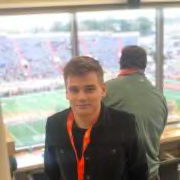

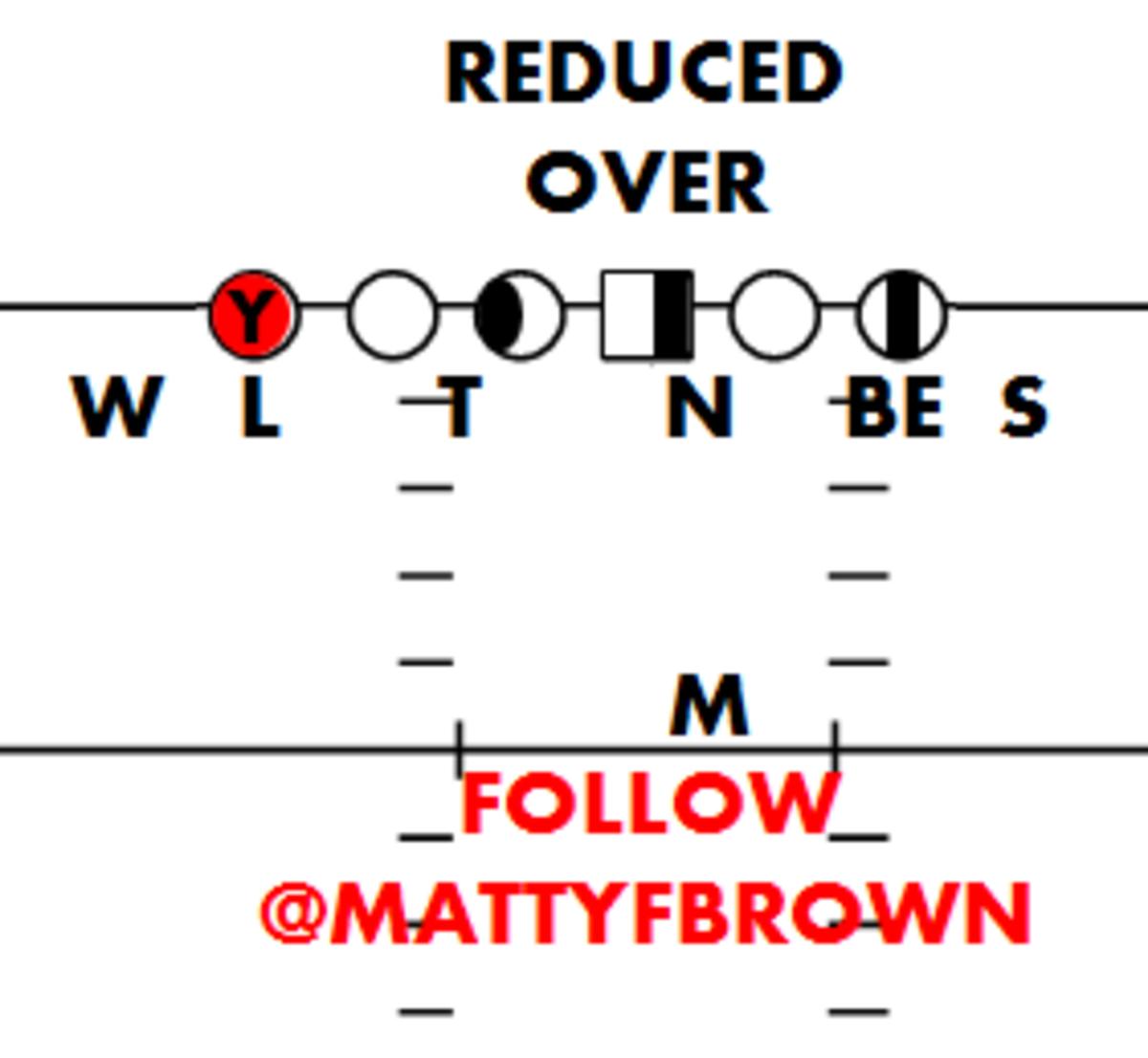

In the last two seasons, Seattle’s defense has further blurred the lines between 4-3 and 3-4. The 2020 campaign saw the team establish bear fronts as its base. In 4-3 personnel, this bear defense was called “stick” in base and “falcon” in nickel. Stick and falcon continued into 2021, where we saw more of a both-sides—almost right-and-left—3-4 philosophy taking place with a hybrid edge pairing of Benson Mayowa and Darrell Taylor out on the field. Hurtt was clearly a driving force behind this.

“3-4 system is something that I’ve really embraced and wanted these guys to do,” he said. “Obviously we’ve started to grow in that [3-4] world, especially with all the teams we see. Like San Francisco being in our division, perimeter run football team. The Rams make you cover the entire field, especially with all the fly sweeps and perimeter screens and whatnot.”

In the past, NFC West offenses had placed Seattle’s defense in a schematic battle it was losing. The 2019 season saw the Seahawks experiment with reduced over fronts called “stone” and “tuff” twinned with staggered hooks and the weak hook safety starting deep before rotating down looking for crossers—detailed in full here.

This defensive approach placed the big end in the weak B-gap in an effort to keep the weak hook-assigned player freer from play-action conflict, and—in theory—able to find race routes. The thinking was similar to Vic Fangio’s 6-2 and 6-1 fronts from 2018—the stuff Patriots head coach Bill Belichick later deployed to defeat the Rams in Super Bowl LIII.

Seattle’s issue, however, was the weak force player down at the line of scrimmage being the SAM—a defender tasked with setting the edge but also with covering the curl-flat zone, including taking wheel routes deep. Versus run fakes away with a fly motion towards him, this SAM was hopelessly conflicted and out-leveraged. Say the fly motion ran a wheel route? It would come open.

Seattle Seahawks cover 3 buzz with 6-1 front v Cincinnati Bengals Flea flicker Post-Wheel pic.twitter.com/ylrBHEAggh

— Ultra Rare Tape (@UltraRareTape) October 18, 2019

Seattle Seahawks cover 3 sky with 5-2 front v Cleveland Browns Play-Action Leak pic.twitter.com/aO3McwHl8D

— Ultra Rare Tape (@UltraRareTape) October 18, 2019

The big end aligning inside to control the B-gap also caused issues versus the 49ers’ two-back weak toss runs, where the fullback would kick out the SAM and the big end would be out-leveraged and on the inside. The weak hook player would be stacking the A-gap, also leaving him in a bad spot with no immediate player in the alley.

“If you watch our defense, fellas, the way we played our defense—the over front—was we played it with a 4b player so essentially we had the D-end inside,” K.J. Wright summarized to the Seahawks Man 2 Man podcast. “... What was really killing us was the boots, because they would rollout and there would be nobody else because he’s inside and the other guy’s dropping.”

In 2020, Seattle’s defense heavily upped its usage of bear/stick to finally triumph over its divisional rivals.

The charting of Sports Info Solutions demonstrates this new base. Taking a look at plays where the Seahawks aligned with two 4is or 3-techniques and one 0-technique nose tackle—plus had four defensive linemen or fewer (to eliminate goal-line packages)—gives us the bear/stick numbers:

- 2018: 8 percent

- 2019: 4 percent

- 2020: 32 percent

Via 4-3 personnel:

- 2018: 11 percent

- 2019: 3 percent

- 2020: 37 percent

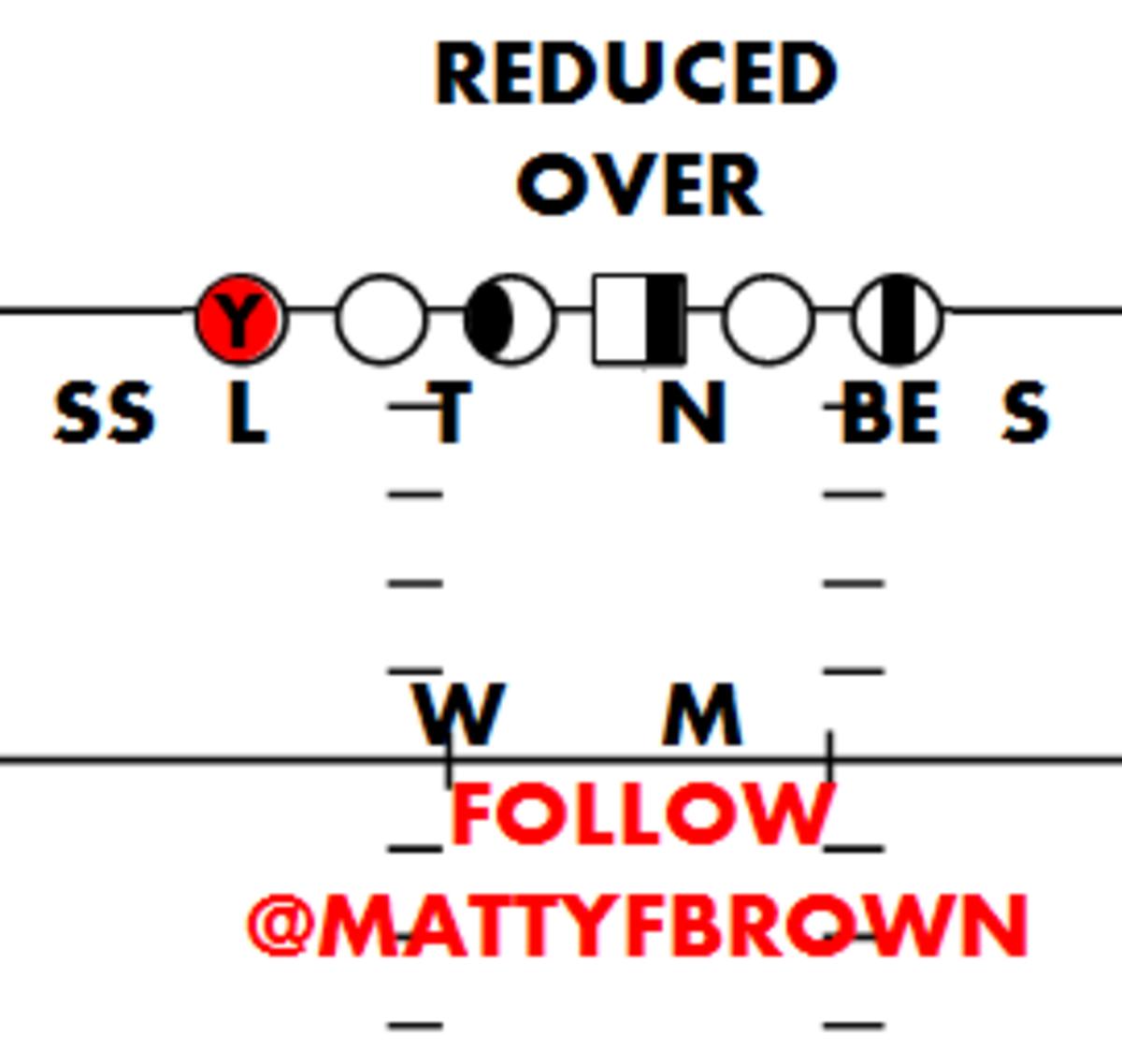

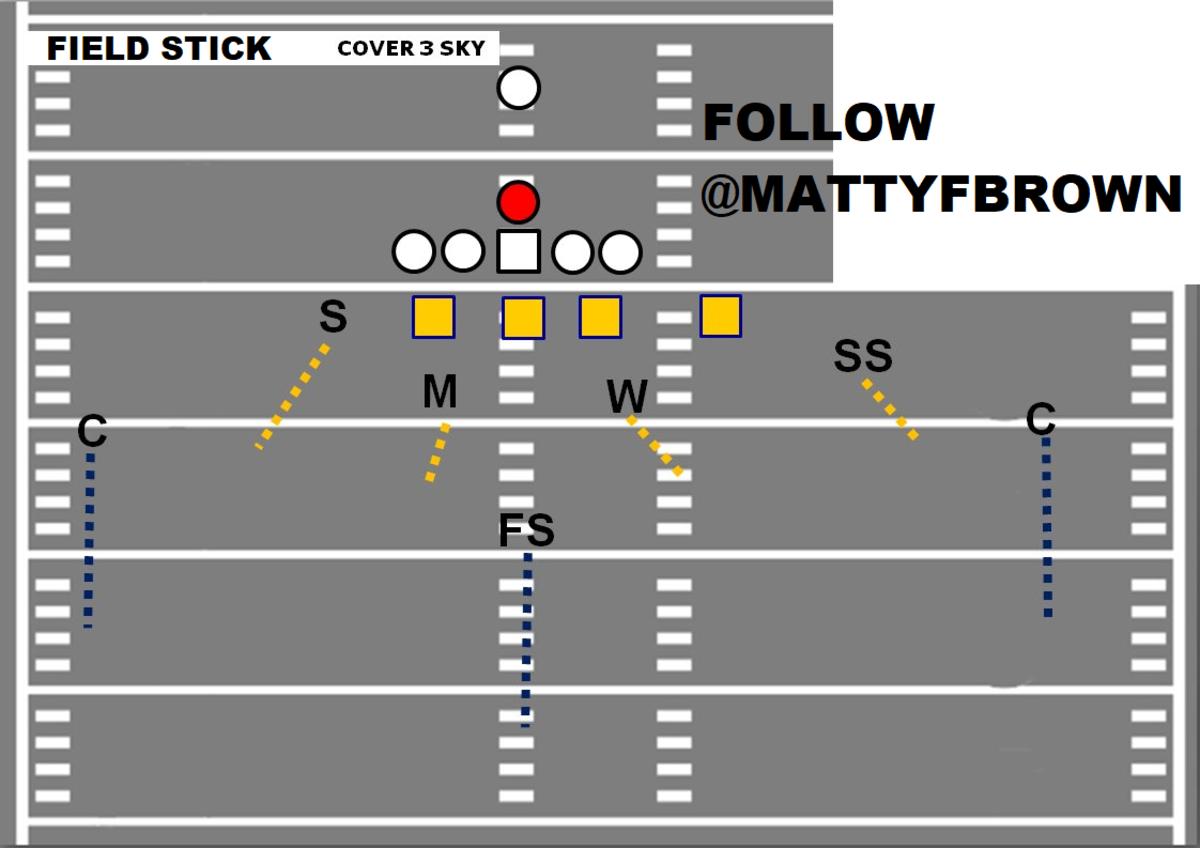

As 2020 progressed, the Seahawks simplified their gameplans, running bear looks more often while utilizing a very basic stick deployment. They would align Wright to the field and Carlos Dunlap to the boundary and run Cover 2 (better spacing this way for coverage and run fit purposes), or they would play Cover 3 sky and place Wright into the short side and Dunlap to the wide.

The Cover 3 put the fourth dropper—the SAM—in the least space possible by aligning him in the boundary. When Wright’s curl-flat drop was threatened by jet motion towards him, he would exchange his zone responsibility with the second-level player behind him, converting to a hook drop that was off low importance versus these jet motion plays.

*V3* D2

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) January 3, 2021

1st and 10

LAR UC 12p pair nub

Woods shift to 3x1✅zone

SEA boundary stick/rocky🐻

Woods✈️: PA post-wheel

SEA C3 Sky

Brooks+Wright zone exchange🔁

JB↪️buzz

K.J.↪️hook

JB takes wheel

K.J's run force+wheel conflict removed

4 yard scramblepic.twitter.com/oI8QcIkNVB

Rush-wise, veteran defensive end Dunlap was given more room to work in, giving the defense a reliable wide rush to the side of the field with greater space. This was an element that proved especially challenging to offenses looking to work the longer developing bootlegs and rollouts on this part of the field.

This meant that in Cover 3, both of Seattle’s edge defenders were placed in little conflict, free to set the edge versus the run. Meanwhile, the interior three of the defensive line removed both B-gap bubbles while the nose tackle aligned head-up on the center. This bought assurance and time for the second-level linebackers, especially important for the weak hook player most often tasked with looking for the deep crossing route. In Cover 2, Seattle would move its front and achieve similar effects.

*V11* D7

— Under Zone X (Frisco)/Phoenix Check/Stick Slasher2 (@mattyfbrown) January 3, 2021

1st and 10

LAR UC 12p trips bunch nub

SEA boundary stick/rocky🐻

LAR bootleg slide

SEA Cover 3 Sky

Brooks⭐️Weak Hook play, finds the issues + robots race/intermediate

Goff forced to run for 3 yards, Wright has angle🐻

Dead play stays dead!pic.twitter.com/J3KZXjJw3C

When asked about the high bear front usage in a Week 13 press conference in 2020, Carroll described the question as “a very astute observation.” Stick and falcon was the defensive schematic takeaway of that year, where the 12-4 Seahawks ended their driest spell of success since 2002 and won the NFC West title.

Seattle, naturally, looked to build upon its bear stuff and make it more complex in 2021.

“I dropped damn-near every play,” Wright described of 2020. “So if I’m the offense, I know wherever K.J. is, he’s gonna drop. So let’s run the ball at him, let’s design our pass game according to what we know they’re gonna be in, right?”

Obviously, last season’s defense, well-planned or not, was disappointing in a variety of areas. As was the team. Hurtt is going to run it back and better.

“You have to have the ability to defend the edges and to be able to cover down, because those teams [Rams, 49ers] are gonna make you defend the field,” the new defensive coordinator explained of his reasonings for liking the 3-4. “And you have to be able to adjust and not make it so easy on the quarterback.”

In 2020, Seattle had planned for Bruce Irvin and Darrell Taylor to be involved as its primary edges, muddying the 3-4/4-3 differences. And in the following season, the plan was for that stick pairing to be Aldon Smith and Taylor. As I wrote after the first week of 2021 training camp, “This is the most 3-4 the Seahawks will have ever looked.”

The available edge-rushing, outside linebacker-types in 2021 did not materialize at the level Seattle expected. That position is now a major need as the Seahawks enter a new offseason.

In part two of this series, I will examine how Carroll's college experiences at USC as well as Hurtt's at Louisville led to development and installation of bear fronts in Seattle.