Sydney Leroux carves own path, going from child troublemaker to U.S. star

Sydney Leroux, 13, had a bleached blond Mohawk. She had tattoos. And club coach Les Armstrong, who was there to scout her for his Sereno Soccer Club team, took one look at her and thought, “Oh my god, this girl is nuts.”

She was also exceptionally talented–her speed and strength unrivaled by any other player on the field. She exuded equal parts defiance and want, and Armstrong thought she had what it took to play for the U.S. national team.

“Growing up, I was wild, that’s really the best way to put it,” says Leroux. “From Day One, I had to be doing something, pushing buttons.”

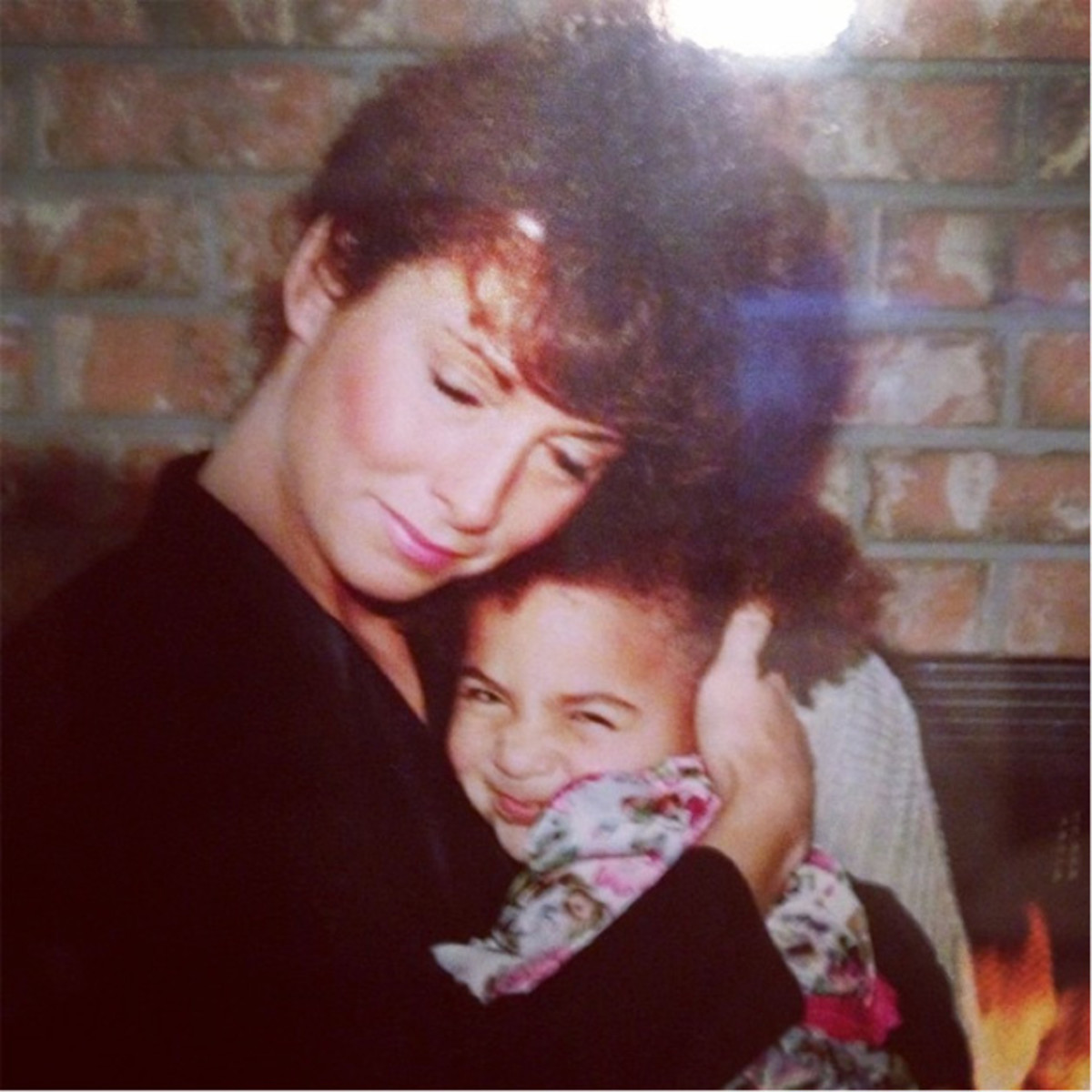

She was born in Surrey, British Colombia, Canada. When she was 3, she scaled the 15-foot fence surrounding the baseball diamond where her mother, Sandi—former member of the Canadian national softball team—was playing in a game; Leroux, dangling in the air, waved to her mother. “My heart stopped,” Sandi says.

Meet the U.S. Women's World Cup team: Forward Sydney Leroux

By the time she started school, everyday she’d find herself in the principal’s office.

“I was a pretty bad kid,” says Leroux. “I would get up when I was supposed to be sitting down. I was in my own world and no one could be a part of that but me. Recess would end, everyone else would come in, but in my head, it wasn’t time for me to come in yet. I’d still be out there kicking the ball.”

After discovering she was reward-driven, Leroux’s mom and teachers devised a star system: if she was good all day, she got a gold star; enough gold stars earned her a sleepover with a friend.

“If I didn’t get a star, I’d be pissed," Leroux said. "I’d try to be so good and then I’d do like one thing–smush a peanut butter and jelly in the math book—and I wouldn’t get a star and I’d have to come home to my mom and try to explain."

From first through sixth grade, on the behavior report cards sent home with her, Leroux would white out the teacher’s grade and replace it with a good grade.

“It would be obvious, childish handwriting. But I’d give it to my mom, totally thinking I was slick,” says Leroux.

When a teacher would call home–this morning Sydney refused to come inside from recess–Leroux, who got home before her mother, would just erase the voicemails.

SI cover: Morgan, Wambach, Leroux, Lloyd and the USWNT World Cup team

By 13, she’d steal her mom’s car: “She had a key ring with like 50 keys, so I would slide the keys off the counter with a towel so she couldn’t hear the jingling.”

They lived on a hill, so she’d put the car in neutral, roll it down the incline, and go pick up her best friend, Efrosini (“Fro”). “We had nowhere to go, we’d just drive around, go to McDonald’s, go out on the beach,” says Leroux.

They’d sit in the sand and talk about their lives, their dreams, their fantasies–a lot of which have now come true.

Leroux always knew that the United States was considered the best women’s soccer team in the world.

“Growing up, it was a thing, it was just something that you knew if you played soccer,” says Leroux. With her mom, she watched the 1999 Women’s World Cup. “On the U.S. team, there were all these big names. And I was like, I want to be that person. I want to be known for being a soccer player and doing something that I love.”

Meet the USWNT 23: The USA's 2015 Women's World Cup team

She also knew she had the chance to play for the U.S. Her father, Ray Chadwick, a minor league baseball player who left her mother when she was two months pregnant, was an American.

He wasn’t on her birth certificate, so she didn’t have automatic dual citizenship, but she and her mother knew that if she could get him to sign the papers, she’d have the chance to play for the U.S.

Leroux’s mom, who worked graveyard shifts at the grocery store so that she could go to her daughter’s games, believed in her Sydney's dream. What made Leroux a handful to raise–that irrepressible urge to experiment, to defy, to take risks–is part of what made her special on the field.

Solo's domestic abuse case looms as USWNT preps for World Cup opener

She had the audacity of a goal-scorer. At the U-14 Canadian national championships, Leroux said to her mother, “Hey mom, if I score 10 goals, can I get a tattoo?” Thinking there was no way she could do it, Sandi said, “Yeah Syd, sure Syd.” Twelve goals later, Syd was in the tattoo parlor—a giant soccer ball emblazoned in flames getting inked into her back—and Sandi was more aware than ever that she had a daughter who could make things happen.

Sandi knew it was time to get her daughter out of Canada. If Sydney wanted to play for the United States, she needed to play in front of American coaches.

U.S. Women's World Cup Team: Sydney Leroux

Leroux landed first with a club in Seattle. She was 13. She was homesick, she missed her mom, and she was playing defense. She felt out of place on the field, she felt out of place off of it–which is where the mohawk comes in. She cut her hair off, shaved the sides, dyed the tips blond. “I figured I didn’t fit in anywhere anyways. Why not?” she says.

While Sandi could do nothing about the tattoos that would emerge over the next few years, the first time her eyes landed on her daughter’s mohawk, she marched her straight to the hairdresser and got it all cut off. “Then I had this ugly haircut for the longest time,” says Leroux. “Pretty much since then I haven’t cut my hair.”

Her mom got the contact of another American coach with a reputation for developing players, and that’s how Leroux eventually arrived in Armstrong’s kitchen, in Scottsdale, Arizona, eating dinner with him and his wife. Sitting across the table from her, it was pretty easy to see she was no hellion, just a scared kid, trying to be brave.

“Staying at the coach’s house, knowing nobody, not knowing where you were going to live, your whole life packed up in bags–she must have been terrified,” says Armstrong.

USWNT's Alex Morgan had late start yield meteoric rise in women's soccer

Armstrong found a family for Leroux to stay with–the first of many. That first home may have been the hardest: she remembers starting to eat dinner before she had prayed.

“They looked at me like I was the devil," she says. "I’m a very open, spiritual person but this family lived by the book and I’d never grown up like that. They made me feel like something was wrong with me. It’s funny now but it wasn’t funny then.”

The second house, the third house, the fourth, none of them worked. “It wasn’t behavioral problems, she was a diligent little solider. She was friendly and kind and she did well in school,” says Armstrong. "It’s just hard to fit into someone else’s family."

It was also hard to fit into a new social world.

“15-year-old girls are mean,” says Leroux. “Everyone has their group of friends, they don’t take into account how you make people feel. I was an outsider, an outcast.”

Leroux was depressed. She slept a lot and she called her mom two to three times a day, crying, begging to go home.

USWNT midfielder Carli Lloyd makes determination her defining trait

“In Arizona, I lost the best part of me, which is my sense of humor, and my ability to make fun of myself,” says Leroux. “I just didn’t have it anymore.”

But she still had the field: “Soccer is what saved me," she says.

Leroux buried herself in the game. She’d train with her own age group boys team, then she’d train with the older boys, then the older girls. sometimes going to three practices a day.

Always, she left an impression: In her very first practice with Sereno, she did a flying bicycle kick that Armstrong says he’ll remember for the rest of his life. Another time she came out to the field with her shirt half-way raised, cream slathered all over stomach, yelling at Armstrong to check out her new tattoo. (“I was like, Holy hell. Never show me anything like that again.”) At Armstrong’s older boys practices, she’d “knock the crap out of them–one of the guys would be laying on the ground, everybody would be laughing, and Syd would ask, ‘Did I do something wrong?’”

The triple-practices, the thousands of miles away from home, the feeling of being absolutely alone–it started paying off. In 2008, after getting her father to sign the documents, Leroux found herself in Santiago, Chile, playing for the U.S. at the U-20 Women's World Cup. She won the Golden Ball and would go on to become the all-time leading scorer for the U-20 team.

Abby's Road: Wambach's motivation, quest for elusive World Cup glory

Off the field, things also got better: she eventually landed with the Wall family–the family that fit. It was the first house Leroux bothered to move into. She had her own room, she taped pictures up on the wall, and Dana Wall, her teammate, “felt like a sister.”

Colleges came to recruit her–including Jill Ellis, then coach of UCLA, and now coach of the U.S. national team.

Ellis knew what Leroux had to offer and did whatever it took to get her, including going to get manicures on a recruiting trip.

(When asked whose idea that was, Leroux laughs, “Well I certainly don’t see it being hers.”)

After Leroux spent one night on the UCLA campus, she told Ellis she was committing to Santa Clara. Ellis’s face dropped, and Leroux grinned: “Just kidding.”

“And that’s how she knew she was going to have a lot on her hands,” laughs Leroux.

Leroux, true to form, kept things interesting: Freshman year she got herself a dog named Boss, dorm policy be damned. She got kicked out of campus housing. (“So Boss and I moved out.”) Just as she always had, Leroux did things her own way. She finished her college career with 57 goals, 23 of them game-winners.

The Power Couple: Sydney Leroux and Dom Dwyer

Fast-forward to today: The flaming soccer ball is covered with other tattoos (“I mean, I love soccer, but no need for a giant flaming ball on my back”); all pictorial evidence of a mohawk was long ago deleted; and Leroux’s hair has grown out, long braids bouncing down her back as U.S. fans watch her run at goal.

She is still the firecracker on and off the field. In her second cap with the senior national team, in an Olympic qualifying match against Guatemala, she scored five goals, tying the record for goals scored in a match. In 2012, she set the record for most goals off the bench (12). And even though she has not been a consistent starter for the team, she is still a mega-star: About 250,000 follow her on Twitter as she speaks her mind about turf, among other things, and makes jokes—her profile reads: “I kick balls for a living.”

This Valentine’s Day, a date chosen based on jersey numbers—Leroux, No. 2, and Sporting Kansas City forward Dom Dwyer, No. 14, announced via social media that they’d gotten married in a private ceremony. Dwyer, like Leroux, is a transplant—born in England, he attended college stateside, established residency in 2009, and could become eligible to play for the U.S., like his wife. In one photo posted on Twitter, the couple is holding hands, wearing their respective jerseys, backs to the camera – DWYER written across both sets of shoulders.

But on the field, she is still very much “Leroux.” She’s on the cover of Sports Illustrated, finger to her lips, next to the caption: Sydney Leroux hears your boos Canada, Sydney Leroux will silence your boos Canada. A previous time she played in front of Canada for the U.S., 20,000 fans were booing her–angry that she wasn’t playing for them. On June 8, facing off against Australia in Winnipeg, she will once again be on Canadian soil, playing for the United States – realizing the dream she had as a kid.

Gwendolyn Oxenham is the author of Finding the Game: Three Years, Twenty-Five Countries, and the Search for Pickup Soccer and the co-director of Pelada. Her website is gwendolynoxenham.com and she can be followed on Twitter @gwenoxenham.