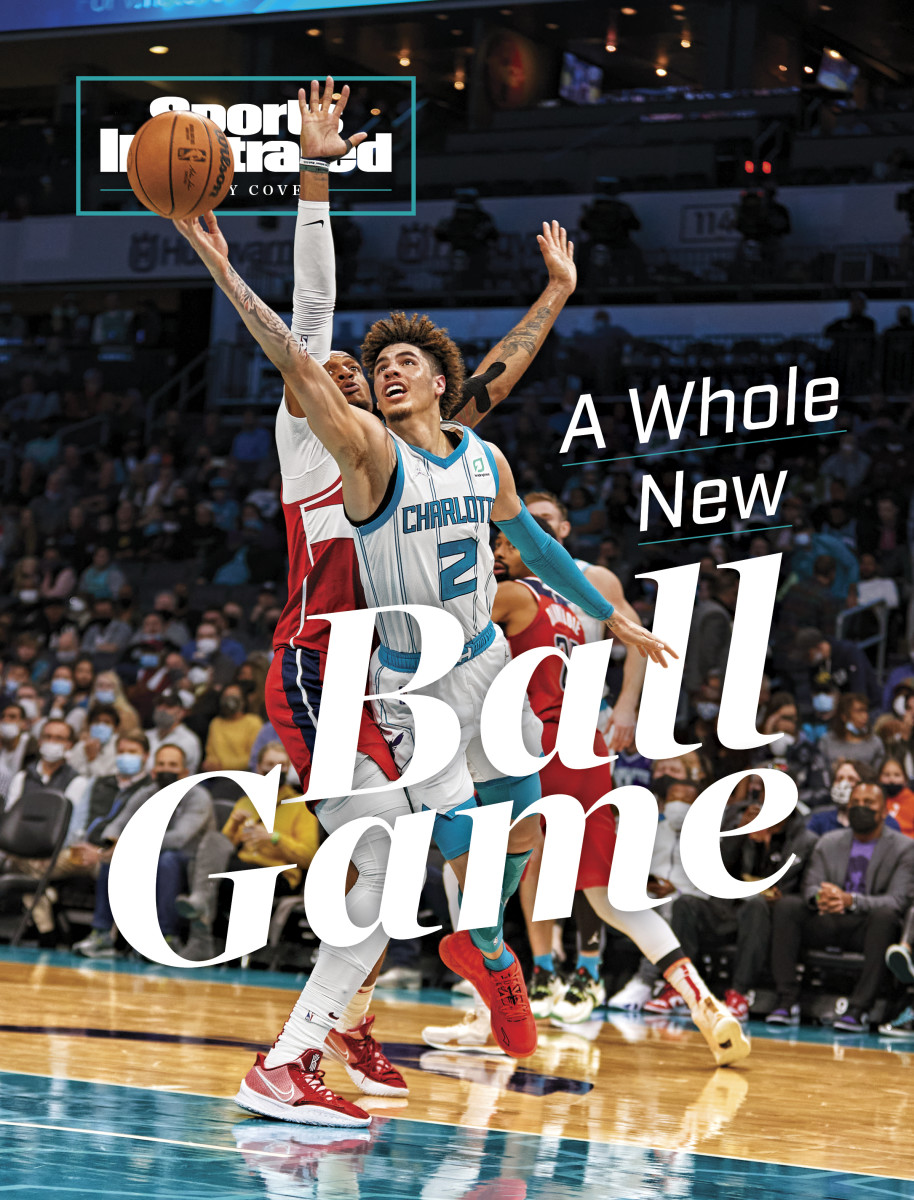

‘He’s Made The Difference’: LaMelo Ball Has Charlotte Buzzing Again

LaMelo Ball is 20, which explains why he suggests meeting at a place where Fruity Pebbles are on the menu. Day & Night Cereal Bar opened in Charlotte last April along a nondescript uptown alley. Patrons include office workers, hotel tourists and, four days a week, a gangly, 6' 7" Hornets point guard. Ball slides his neon-yellow Lamborghini into a parking space on North Church Street and orders a Cosmo & Wanda shake, a blend of Froot Loops and the berry pieces of Cap’n Crunch. “There’s something like this back in L.A.,” he says between pulls from an oversize straw. “Cereal is undefeated, bro.”

Looking for a sense of entitlement from a player who won Rookie of the Year despite playing just 51 games last season? It isn’t there. After the Hornets lost in last spring’s play-in tournament, Ball could have returned to his native SoCal and basked in his instant stardom. Instead, he stayed in Charlotte, toggling between the practice facility and his downtown condo, dividing his time among jump shots, deadlifts and video games. “I don’t really need a lot,” says Ball. “I don’t really like going out too much. Just be at the crib. Gym, right down the street. It’s the perfect situation.”

Looking for a whiff of arrogance from the high school phenom with a reality-show credit on his IMDb page and a signature shoe as a teenager? His teammates haven’t sensed it. “With those type of guys, you always think they’re going to come in with a cocky attitude,” says forward Miles Bridges. “But it’s crazy because Melo, he’s just the complete opposite. He’s just a hardworking kid that wants to get better.”

Looking for traces of the bombastic personality his father, LaVar, often showcases? Ask LaMelo, one of the most gifted passers in a generation, to deconstruct some of his jaw-dropping assists and receive a quizzical look. “I’m just making it up,” Ball says. “I see someone; I throw it. Whatever comes to my mind.”

There’s a breeziness to LaMelo that belies his age, an uncanny ability to simply live in the moment. The No. 3 pick in the 2020 draft delivered 15.7 points, 6.1 assists and 5.9 rebounds per game as a rookie, including 18.1 points per game after being installed as a starter in February. Before Ball broke his right wrist in late March, Charlotte was in the thick of the playoff chase, notable for a team that has made just three postseason appearances since it entered the league as the Bobcats in ’04—and never advanced past the first round.

Ball, whose numbers are up significantly this season, has given the once-anonymous franchise a face. Fans renewed their season tickets at a 90% clip, with 2,200 new ones sold, putting the Hornets among the NBA’s top-five ticket sellers in the offseason. His No. 2 jerseys, meanwhile, are flying off shelves and onto the backs of fans in the Spectrum Center. “My first two years, it was only packed if we played the Lakers, the Knicks or the Celtics,” says Bridges. “A lot of fans came to see them. Now fans actually come to see us. That’s Melo.

“He’s made the difference.”

Hornets coach James Borrego developed his philosophies on player development in San Antonio, where he did two stints as an assistant. He watched the Spurs’ staff, led by Gregg Popovich, forge bonds with players off the court, which built the foundation for success on the court. For example: Tony Parker, the 28th pick in the 2001 draft, was an All-Star by his fifth season in part because of changes the Spurs made to the release of his jump shot. What people didn’t see, says Borrego, was all the time Chip Engelland, the team’s shot doctor, spent building a relationship with Parker. “Once Tony trusted Chip, and Chip had the buy-in from Tony,” says Borrego, “the shot just became a product of that relationship.”

Borrego, 44, has started to build a similar relationship with LaMelo. Last spring, as COVID-19 vaccines restored a sliver of normalcy, Borrego invited Ball over for dinner. By midsummer Ball was a frequent guest. He swam in Borrego’s pool, played basketball with his three kids. A standing order of pizza and lemon-pepper wings was ready whenever Ball decided to drop by. Their conversations were never about basketball. “Just family,” says Borrego. “And life.”

Ball’s journey has been well chronicled by magazine writers, cable television networks and reality TV cameras. It began in Chino Hills, Calif., on a double-rimmed backyard hoop a few inches higher than the 10-foot norm. LaMelo joined his older brothers, Lonzo (now the Bulls’ point guard) and LiAngelo (who plays for Charlotte’s G League team), on the court when he was 4, and his extraordinary ballhandling immediately stood out. He had a passion for football, too, which LaVar cleverly discouraged; he would let his son play only if he wore cleats to school. “That,” says LaMelo, “ended that.”

The Ball backyard was the neighborhood’s premier pickup spot, with LaVar routinely pitting his three preteen sons against kids several years older. For all of Ball’s bravado, his coaching fingerprints are all over LaMelo’s game. LaMelo thrives in transition because when competing against bigger, stronger kids, playing fast was the only way to score. “My boys are the only ones who got to the NBA and had to slow down,” says LaVar. LaMelo is a willing passer, in part, because LaVar stressed the importance of getting the ball up the floor and getting teammates involved. He effortlessly flicks underhanded assists the full length of the court because LaVar had him throw that exact pass countless times in practice.

Ball spent the better part of his teen years hopscotching the globe, playing in pro leagues in Lithuania and Australia while participating in a 13-country tour LaVar organized for the JBA, the league LaVar simply invented. But don’t tell LaMelo the path was his father’s idea. “Everything damn near felt like my choice,” LaMelo says. Even so, the Lithuanian experience was lousy—the frozen climate, the language barrier, the long minutes on the bench. “The team wasn’t taking him seriously,” says LiAngelo, his teammate on BC Prienai. But LaMelo, then 16, appreciated the extra work he put in before and after practice with LaVar, which he was able to do without the responsibility of academics. “I take it all as a learning experience,” says Ball. His stint with the Illawarra Hawks lasted just 12 games, but he showed enough to be named the National Basketball League’s Rookie of the Year. “Australia low-key was cool,” says Ball. “That was the best overseas experience.”

Mitch Kupchak, the Hornets’ GM, liked what he saw in Australia. Ball was a blur, a fearless, physically gifted playmaker with uncanny vision. “Some of the guys he was going up against were in their 20s and 30s,” says Kupchak. “They’re strong and physical, and they compete. If you’re afraid of contact or afraid of getting physically worn down every game by these guys, then that’s not a good thing. We didn’t see that.” Hawks officials raved about Ball’s work ethic. “Because of the way he bounced around and all the attention the family got, we were looking for something bad—bad teammate, into himself, partier, whatever,” Kupchak says. “There was none of that. It was pretty much he stayed in his apartment, loved the game, worked, was a good teammate, that kind of thing.”

A few weeks before the 2020 draft Kupchak, Borrego and assistant GM Buzz Peterson flew to Los Angeles to meet with Ball. Borrego asked Ball what he valued. Family, Ball said. Borrego was sold. Kupchak was a little skeptical about Ball’s unorthodox shooting mechanics, including a low release point. But during an hourlong workout, Ball drilled enough threes to make Kupchak believe he could make them at the NBA level. As for an L.A.-bred, heavily hyped prospect’s desire to play in Charlotte? “You play in Lithuania,” says Ball, “anywhere in the States is cool.”

The Hornets’ faith was quickly rewarded. A shortened, postbubble training camp kept Ball on the bench to start the season, but, he says, “I knew that wasn’t going to be the case for long.” An injury to Devonte’ Graham in February gave Ball a chance to start, and he seized it. Charlotte, dead-last in the NBA in pace in 2019–20, jumped to 18th last season. This year the Hornets are in the top five, and Ball-to-Bridges has become one of the NBA’s most fearsome transition threats. “He sees everything,” says Bridges. “That’s just the beauty of playing with Melo. He knows where you want the ball, and he gets it to you.”

From behind a desk in his office, Borrego pulls up a LaMelo clip that always makes him smile. It’s not a no-look pass or a buzzer-beating triple but a series of decisions that Borrego believes best exemplifies Ball’s development. With less than two minutes to play in the fourth quarter and the Hornets clinging to a three-point lead over the Knicks on Nov. 12, Ball called for a screen from Bridges. When the defender slipped it, Ball called for another. Again, the defender stayed in front of him. From the sidelines, Borrego anticipated Ball would go one-on-one or toss up a contested 25-footer. Instead, Ball calmly signaled Bridges to come out again. This time, the screen stuck. After drawing the second defender, Ball flipped it back to Bridges, who drove for a layup and a foul. The Hornets went on to win. “I had a moment by myself in this arena full of people going, That was pretty cool,” says Borrego. “His instinct said, Go make a play. His growth pushed him to find a better shot.”

LaMelo insists: He didn’t say what you think he said. In October, Ball and Jay-Z—hip hop mogul, former Nets owner and Brooklyn’s most famous living citizen—crossed paths at halftime of a Hornets-Nets game. The exchange was caught on camera. Amateur lip-readers quickly flooded social media with transcripts that suggested Jay-Z asked LaMelo about playing in Brooklyn and Ball replying that he was good in Charlotte. “It wasn’t like that at all,” says Ball. “It was something very simple, like, ‘Where you going after this?’ I’m like, ‘Oh, we back to Charlotte.’ ” The endless deconstruction of the chat baffled Ball. “I have one convo,” he says. “Man, I don’t even know.”

It’s the cost of being the hope of a franchise.

In his talks with Ball, Kupchak frequently brings up the greatness of Kobe Bryant, whose development he helped oversee as an executive with the Lakers. The practice habits and offseason workouts, the competitiveness that sharpened a singular focus. Kupchak won’t compare LaMelo to Kobe but notes a similar unflappability on the floor. “Whether it’s making a bad pass or two because maybe he tries to stretch the limits of the pass, he’ll do it a third time,” says Kupchak. “If he misses two or three threes, and there’s two minutes left to the game, he’ll take another one. He doesn’t get rattled, and he has great confidence in his abilities.”

Borrego likens the process to what Popovich went through with Argentine guard Manu Ginóbili: The coach walked the fine line between holding Ginóbili accountable for mistakes and allowing him to flex his creativity. “Both Melo and Manu are fearless,” says Borrego. “The challenge is fitting that fearless spirit within a system.” Charlotte has veterans like forward Gordon Hayward and guard Terry Rozier, but Borrego tells Ball: You are the general. You have to control the gym. When they watch film together, it’s usually clips of split-second decisions Ball makes. “I say to him all the time, his basketball IQ is going to continue to grow,” says Borrego. “He has great feel, great instinct. Now it’s about the IQ growth in understanding the league and personnel, not only of his teammates but of who we’re playing, who we want to attack.”

Watch NBA games online all season long with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Borrego also sees a curiosity in Ball similar to what helped drive Ginóbili. Ball is the most vocal player in film sessions, chiming in on nearly every play. “When he first came in, I thought he’d be more quiet, reserved, disengaged,” says Borrego. “He’s been completely opposite. He’s more engaged, more curious, more vibrant than I could have ever imagined.”

Ask Ball about the comparisons to former greats and you are once again reminded: He’s 20. He grew up in the shadow of Bryant but can’t pinpoint similarities in their games. “I don’t really compare myself to anybody,” says Ball. He was a toddler when Ginóbili started winning championships and admits he has not watched much tape of him: “I heard he was cold, though.”

After scooping out the last few bits of Cap’n Crunch from his frosty treat, Ball slides off a stool and disappears down the alley. It’s back to the gym to get up a few more shots. Then back home for a few hours in front of the Xbox.

Occasionally, Bridges says, he will try to lure his teammate out. But more often Ball entices Bridges into a game of NBA2K or Mortal Kombat or a night spinning through NBA League Pass. “You would think with [7.5 million] Instagram followers he’d be all over the place,” says Bridges. “But he just likes to be at home.”

For someone so comfortable in his own skin, it’s not surprising Ball prefers his own avatar, too. “He’s always Charlotte,” says Bridges of their NBA2K matchups. “He’s got to score 50 with himself.” And why not? It’s fun to be LaMelo Ball.

• He Nearly Died on ‘Drive to Survive.’ Now He’s Faster Than Ever.

• Tom Brady Wins the 2021 Sports Illustrated Sportsperson of the Year

• Billie Jean King Wins SI’s Muhammad Ali Legacy Award

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.