How Sports Illustrated Captured the Life and Legacy of Hank Aaron

Before all of the Sports Illustrated covers—for the 715th home run, and the 755th home run, and everything in between and after—Henry Aaron was the subject of one paragraph in a piece about the pennant chances of the 1956 Milwaukee Braves:

“Of all the fine-looking youngsters in the National League, none has been chasing a ticket to the Hall of Fame with any more singleness of purpose than this slender 22-year-old from the mud flats of Mobile. He began the season slowly, but [manager Fred] Haney just looked at this young man with the wrist-popping swing and said, ‘He’s still below his potential. He’s a .330 hitter—at least—and I haven’t the slightest doubt that he’ll be up there before long.’ ”

This was the first time that Aaron was written about at length in the pages Sports Illustrated. It’s a snippet that might have easily been proved ridiculous. To invoke the Hall of Fame for a 22-year-old? To suggest that he was somehow still below his potential right as he was tearing up the National League? But now it reads as understated. Of course he was chasing the Hall of Fame. Of course he would show himself to be one of the best hitters not just in the league, not just of his generation, but of history. How could he be anything else? (And his manager was right: Aaron did indeed end up winning the NL batting title that year and hitting .328.)

Aaron, whose death was announced Friday at the age of 86, was one of baseball’s most iconic figures, revered for his work off the field as much as on it. To read his life through the pages of Sports Illustrated is to remember an incredible talent who endured vicious racism as he cemented his legacy as one of the best to play the game.

He debuted in 1954, the same year that the magazine did, and was a fixture in its pages for decades to come. (While he’s not featured on the cover of the first issue—the hitter there was teammate Eddie Mathews—Aaron did play in the game pictured and went 2-for-3.) By 1957, at the age of 23, he was the subject of a profile that described his at bats in the language of a religious experience: “It is then, however, during these brief moments, that the thousands wake up and realize, almost too late, that here before them stands one of the divinely gifted few. He looks small down there in the batter’s box and not very deadly at all. He stands well away from the plate, toward the rear of the box, languidly swinging the yellowish-white bat in a low arc. Then the pitcher stretches and throws, Aaron cocks his bat, and the ball comes in. At the last moment he strides forward and leans toward the baseball; the bat comes whipping around in a blur almost too fast for the eye to follow and there is a sharp, loud report. A white streak flashes through the infield or into the outfield or over the fence, and Henry Aaron has another base hit.”

It was hitting like this that had him chasing the home-run record a decade and a half later. It had him, too, staring down racist threats that made the experience hellish:

“Is this to be the year in which Aaron, at the age of 39, takes a moon walk above one of the most hallowed individual records in American sport, the 714 home runs hit by George Herman Ruth? Or will it be remembered as the season in which Aaron, the most dignified of athletes, was besieged with hate mail and trapped by the cobwebs and goblins that lurk in baseball’s attic?”

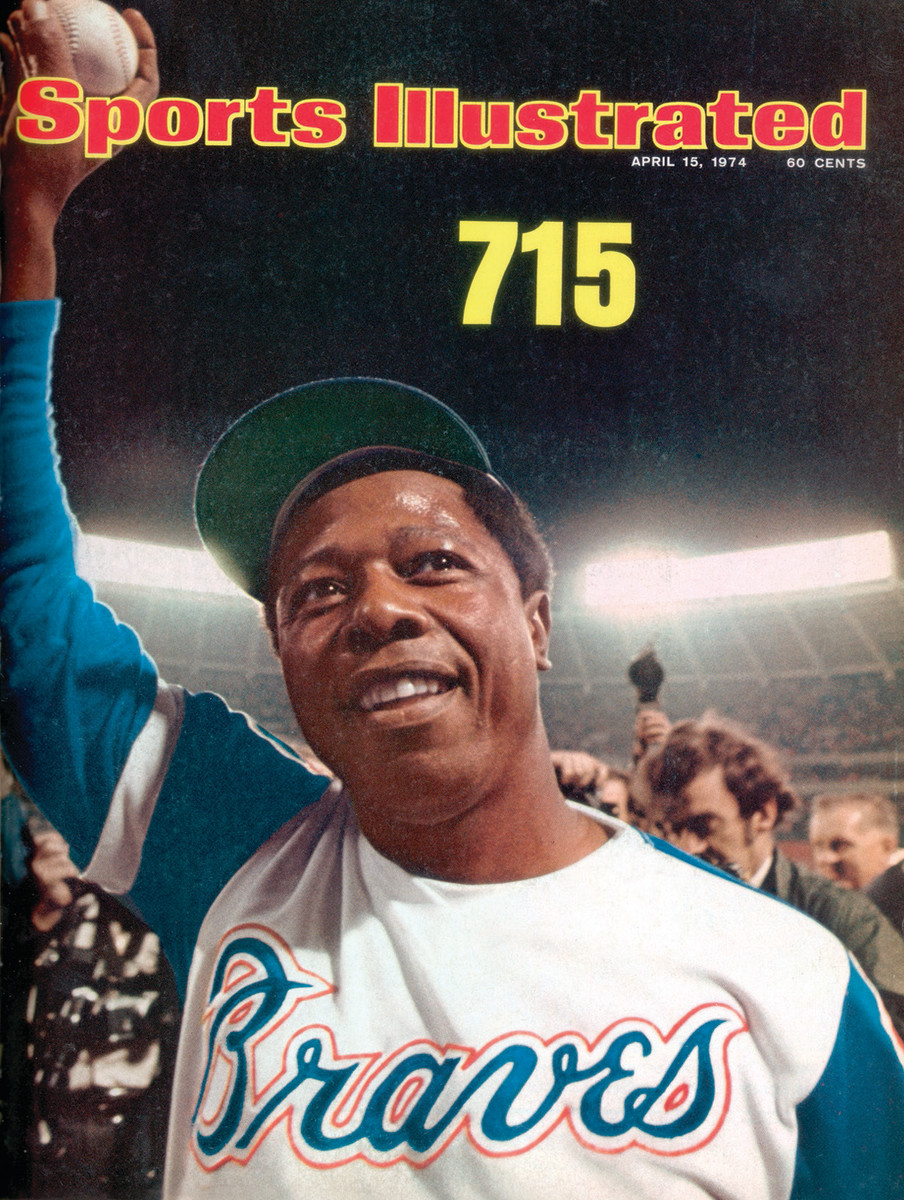

When he hit No. 715, the lead sentence of the resulting magazine cover story made it obvious that this could not be a moment of celebration for him so much as it was one of simple relief: “Henry Aaron’s ordeal ended at 9:07 p.m. Monday.” And when Sports Illustrated visited him at home in 1992, nearly two decades later, he made clear that the brutal lessons of that season’s threats never left him: He still would not sit with his back to the door of a restaurant, or finish a drink of water that he had left unattended, or let his guard down in a room of strangers. “It should have been the happiest time of my life, the best year,” he said of 1973. “But it was the worst year. It was hell. So many bad things happened. … Things I’m still trying to get over, and maybe never will. Things I know I’ll never forget."

“What does it say of America that a man fulfills the purest of American dreams, struggling up from Jim Crow poverty to dethrone the greatest of Yankee kings … yet feels not like a hero but like someone hunted, haunted?” the piece went on to say.

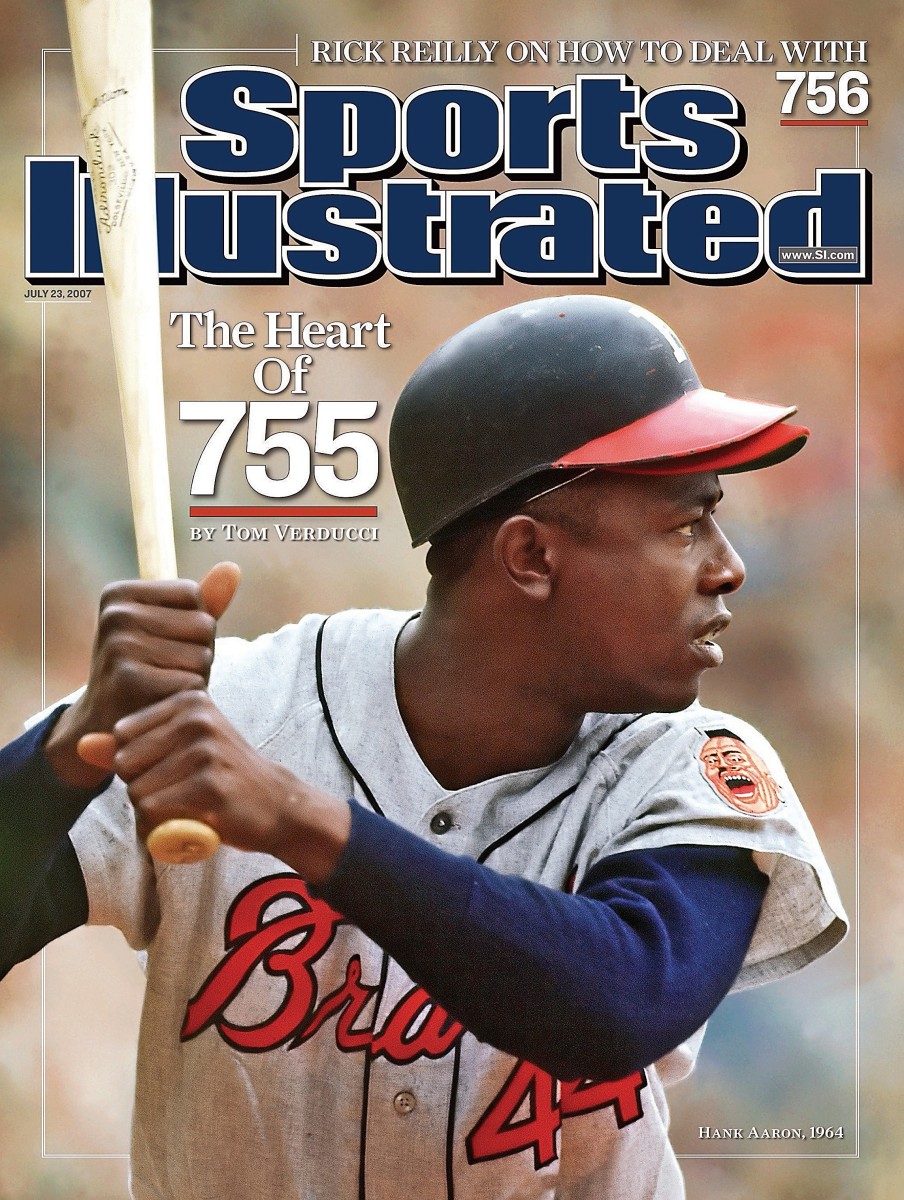

In 2007, as Barry Bonds closed in on Aaron's home run title, the Hall of Famer graced the cover one last time: The Heart of 755, it read. “I guess,” Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson said in the piece, “you can call him the people’s home run king.”

But the last major piece was still yet to come. It ran on the occasion of Aaron’s 80th birthday, in 2014, when he was honored with a painting in the National Portrait Gallery—a distinction that rightfully positioned him as an icon not just of baseball but of culture, not just of sports but of civic leadership, not just of Mobile or Milwaukee or Atlanta but of America.

“As friends from Rachel Robinson to Reggie Jackson to Bob Uecker looked on,” the story went, “two treasures were joined—the Smithsonian and Henry Aaron, Institute and institution, twin repositories of our national memory—and the great man himself revealed the hard-won wisdom of his remarkable life: ‘My mother always taught us to do unto others as you would have them do unto you.’”

More Hank Aaron Stories From the SI Vault and SI.com:

• SI's Best Photos of Hank Aaron

•At 23, Hank Aaron Is Already the League's Best Right-Handed Hitter - Roy Terrell, 1957

• Henry Aaron May Be Getting Older, but He's Still Terrorizing Every Pitcher He Faces - Jack Mann, 1966

• Henry Raps One for History: Aaron Collects Hit No. 3,000 - William Leggett, 1970

• Despite Losing the Home Run Record, Hank Aaron Will Always Be "The People's King" - Tom Verducci, 2007

• Where Are They Now: The People Behind Hank Aaron's Record 715th Home Run - Stephanie Apstein, 2014