Scherzer-Girardi Fiasco Reveals Worst (and Funniest) of MLB's Sticky Stuff Crackdown

Welcome to The Opener, where every weekday morning you’ll get a fresh, topical column to start your day from one of SI.com’s MLB writers.

For 24 hours, MLB’s crackdown on foreign substances went perfectly smoothly.

When the new enforcement protocol went into effect Monday, it offered some natural rebuttals to a few of the loudest arguments against it. The idea that umpires’ impromptu checks of pitchers would drag down pace of play? The mini-patdowns took place at the end of innings, when the pitchers were already walking off the mound, and they were over in a matter of seconds. The idea that managers could weaponize requests for checks against opposing pitchers to disrupt their rhythm? With the new guidelines requiring that every pitcher be checked, without a manager needing to request it specifically, it didn’t seem like any gamesmanship was afoot. There were still valid reasons to be concerned about the larger context of the crackdown. But these logistical details did not seem to be among them.

A lovely 24 hours! And then you hit Tuesday night, when Phillies skipper Joe Girardi asked for a mid-inning check of Nationals starter Max Scherzer, and it all went to hell.

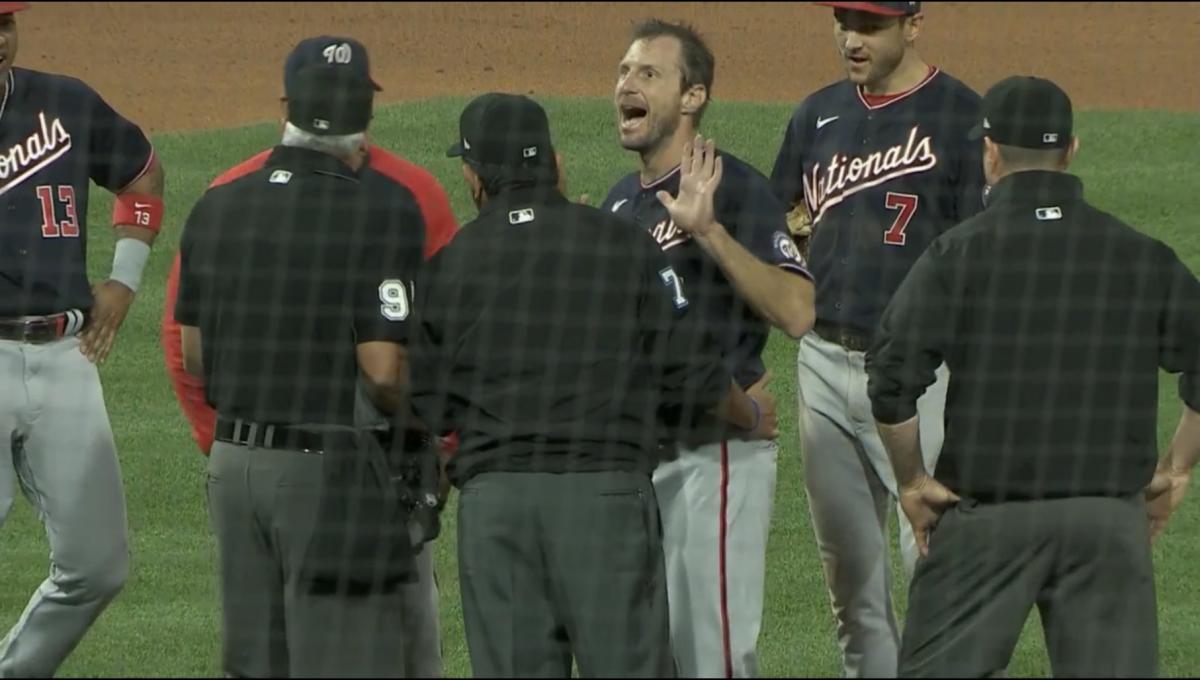

It was a moment that neatly demonstrated the worst of what this enforcement might possibly look like; it was also a moment that was deeply, weirdly funny, with a mix of personalities ideally suited to the over-the-top drama of this screwed-up theater. It was profoundly stupid and—with apologies to this MLB debut home run from 20-year-old Wander Franco—it was also arguably the most compelling baseball moment of the evening.

There are three categories of viral baseball moments. There are game highlights—moments that are either so great or so painful that they simply demand to be shared. There are memes—moments that we see ourselves in, ripe to be edited and recontextualized, getting endlessly replicated in miniature out across the internet. And then there are images just so striking, so weird, that they speak for themselves. There is no way to make them more resonant, or more important, or more humorous; there is nothing to be gained with additional context or analysis or a joke. There is no need for an editor’s hand here. All there is to do is share and stand back.

That last category is for images like this:

Or this:

Or this:

What context can you add that makes all this feel any less absurd? What joke can make it any dumber? None—this is a universe contained within a triptych, gloriously stupid, speaking for itself.

The protocol states that umpires will check starting pitchers for substances at least two times per game. If an ump sees reason to be suspicious about a pitcher, he can conduct additional checks, or an opposing manager can ask for one. (But—and this is important here—the guidance states that a manager will be disciplined if he makes such a request in bad faith.) By the bottom of the fourth inning Tuesday, Scherzer had already been checked twice, and the umpires had not detected anything unseemly either time. But Girardi requested a third check. And Scherzer, famous for his intensity, was steamed—visibly frustrated as he threw his hat to the ground and unbuckled his belt with gusto. (The umps once again came away without finding any evidence of sticky stuff.) When he left the field later that night after his fifth inning of work, Scherzer stared down Girardi, who began jawing at him, and it unraveled from there. Girardi was ultimately ejected.

Phillies manager Joe Girardi and Max Scherzer got into a stare down after Girardi requested umpires check Scherzer for foreign substances for a third time.

— SportsCenter (@SportsCenter) June 23, 2021

Girardi was ejected after the altercation. pic.twitter.com/3B6kGLbudL

It might have seemed like a clear example of a manager pushing the limits of what it means to request a check in good faith—Scherzer had already been examined twice, there had been no signs of any illegal substances, and yet the manager called for a third check mid-inning, when it was bound to more disruptive to the pitcher’s rhythm. But there’s something of a gray area around just what qualifies here as “bad faith,” with no definition given in the memo, and there was pushback on this idea from Girardi. As it happened, he had been asked before the game about what it might take for him to request an examination, and he’d dismissed the notion of trying to game the system: “I’m not going to play games,” he told reporters. “That’s silly. It’s just, if you see something that’s clear-cut, you’ll probably ask them.”

After the game? Girardi held firm. He said that his curiosity had been piqued by Scherzer wiping his head and touching his hair. “It was suspicious for me. … I didn’t mean to offend anyone. I’ve just got to do what’s right for our club,” he said.

It does not stand to reason that incidents like this will become the norm. Most other checks Tuesday passed without incident. (Though some pitchers were happier to receive them than others.) Not every manager will be willing to test the limits of how the league might interpret discipline for “bad faith,” and not every pitcher will be a well-regarded veteran in union leadership, like Scherzer, who is willing to start undressing just to make a statement. But it still offered a glimpse of what this new enforcement might look like at its worst. It was weird, and funny, and dumb. It was also a mess.

Scherzer, for his part, was adamant that he’d had nothing on him. (“I would have to be an absolute fool to use something tonight,” he said of the first game he’d pitched under the new protocol.) He said that he’d been running his hands through his hair in an attempt to pick up some sweat to help his grip on a cool night. And he did not blame Girardi so much as he blamed the commissioner who had set up a system that allowed for this in the first place, a system where these images were not highlights, or memes, but quiet monuments to their own absurdity:

“These are Manfred Rules,” he said. “Go ask him what he wants to do about this. I’ve said enough.”

More MLB Coverage:

• MLB's Pitch-Doctoring Crackdown Presents New Problems for the League

• Jacob deGrom's Dominance Is Beyond Comprehension

• For Ohtani and Others, an Interpreter Is So Much More Than You Think

• Tragedy and Hope: A Prospect, a Scout and a Pop Fly