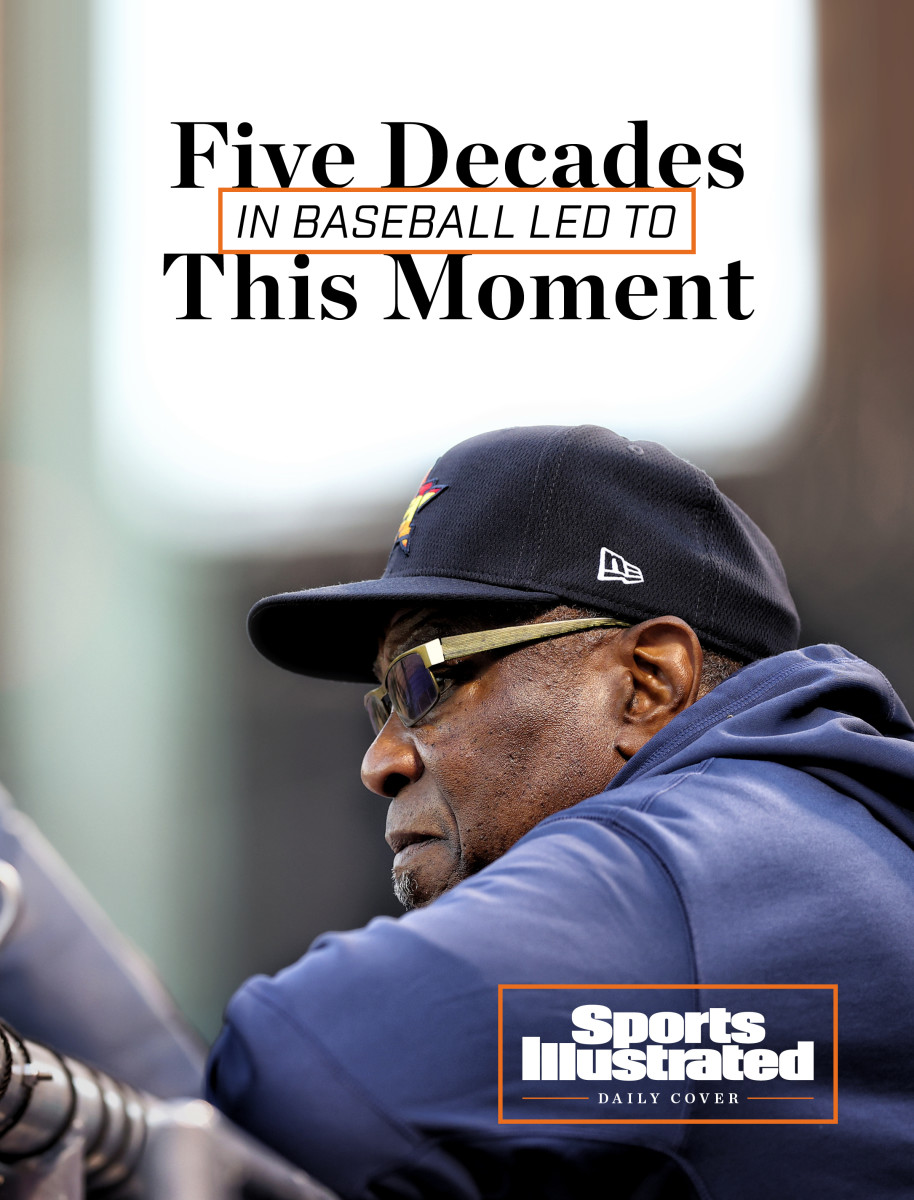

Dusty Baker's Time Is Now

To be a teenager on June 19, 1967, and especially one of color, was to see America as a 20-quart iron stockpot approaching a hard boil. The heat intensified with every headline. In just the previous three months, Muhammad Ali refused military service, massive protests arose in San Francisco and New York against the Vietnam War, and a breakout star named Jimi Hendrix was among the many musicians to take the stage that weekend at the Monterey Pop Festival, the launching pad to “The Summer of Love,” a younger generation’s vocal counter to war and inequality.

The simmer loomed especially ominous in the South. Tampa was a tinderbox that day after three days of race riots related to the police shooting of a Black man, while in Montgomery, Ala., 300 Black people marched four blocks to the capitol to protest what they called police militarism.

“I prayed I would not be drafted by the Braves,” says Dusty Baker, who had turned 18 years old just four days earlier and, yes, was drafted by the Braves nine days before that.

Baker knew that the Braves not only played in Atlanta but also that their farm teams were in places below the Mason-Dixon line, such as Lexington, N.C., Kinston, N.C., Austin and Richmond. Baker was the only Black person at Del Campo High in Sacramento until his younger brother, Robie, followed him two years later.

What happened that day in Los Angeles is the switching of life’s train tracks, the sharp bend of the river of fate. It is why Baker, now 72, will be in the dugout of the Astros for Game 1 of the World Series Tuesday night—against the Braves, no less—trying to check the last box of what is one of the longest, most beguiling, most unbelievable bucket lists of any baseball life. It is the story of how two men who are no longer here to see it, Henry Aaron and Baker’s father, Johnnie B. Baker Sr., made this painfully long quest possible.

“Life experience,” says Astros bench coach Joe Espada. “That’s what sets Dusty apart as a manager. He is the best I have seen at taking this.”

Espada pulls from his back pocket his phone, the symbol of the connected world.

“And I can’t say ignore it, because that’s impossible, but he turns it down. He turns down the noise and has the self-confidence to rely on his wisdom and life experience without regard for the noise.”

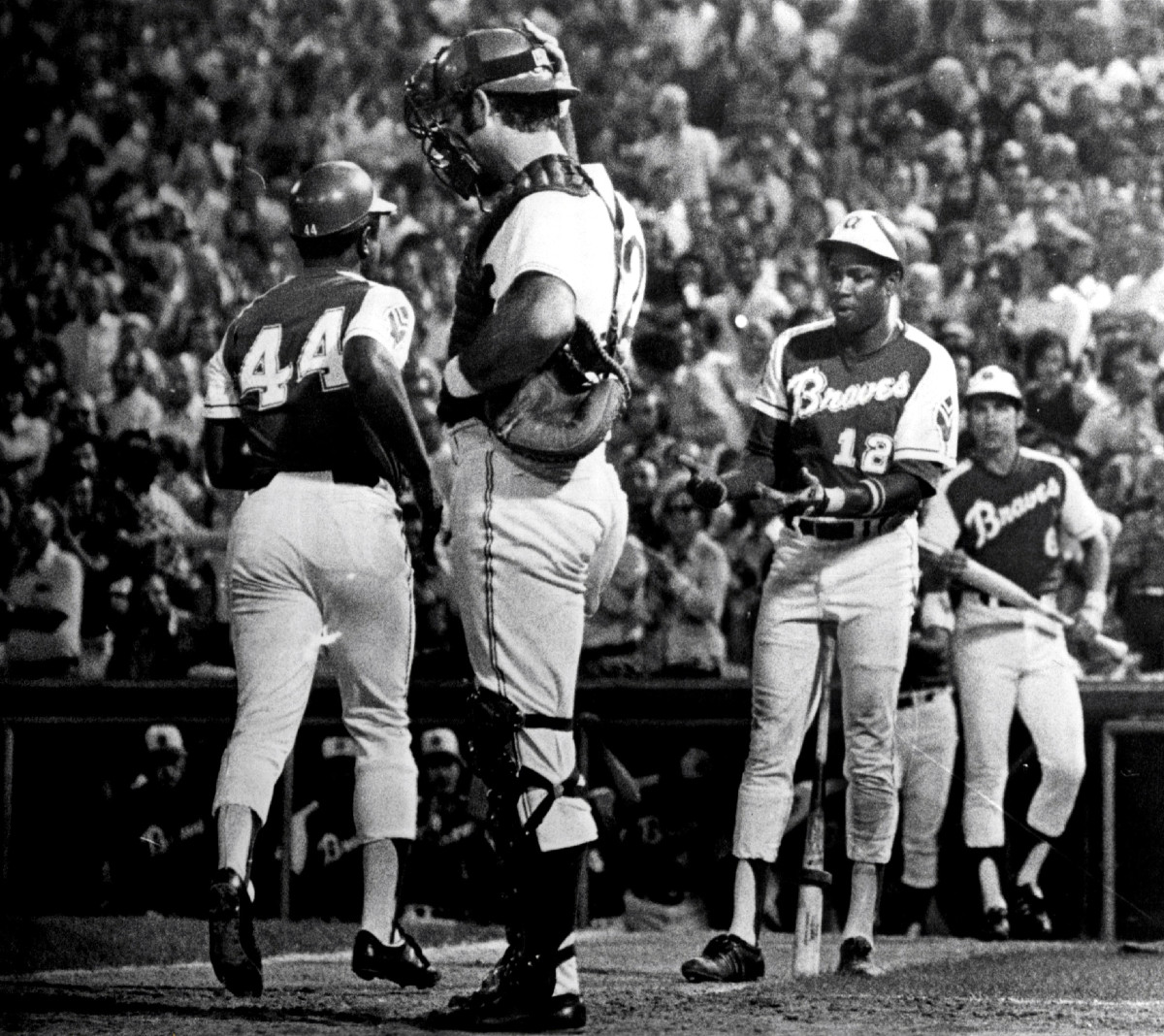

Baker is the Forrest Gump of modern baseball. He has been there in uniform for Aaron’s 715th home run (he was on deck), the first high five (he and Glenn Burke), the first NLCS MVP (he won it), Reggie Jackson’s three-homer World Series game, Fernandomania, the 1989 World Series earthquake, Barry Bonds’s record-breaking 71st home run, the largest blown lead of a World Series potential clincher (2002 Game 6), The Bartman Game (2003 NLCS Game 6), the only time batters reached consecutively on each of the four ways to get on base without putting the ball in play (2017 NLCS Game 5) and the cleanup from the Astros’ sign-stealing scandal.

His professional baseball life experience traces to that June day in 1967, a Monday. The Braves were playing that night in Los Angeles against the Dodgers. They flew Baker and his mother, Christine, from Sacramento to Los Angeles.

“My dad didn’t know,” Dusty says.

The Braves had drafted Baker in the 26th round and were offering him second-round money. Johnnie B. Sr. did not want his son to take it. He wanted his son to take the basketball scholarship offer from Santa Clara. He might even play football, too, in the same backfield as quarterback Dan Pastorini. It wasn’t about the sports, though. It was about getting the college education he never did.

Johnnie B. Sr. worked on Air Force radar equipment by day and earned a few more bucks at night at Sears. He was so strict he was known around town as “Mr. Baker” and thought nothing of chastising townspeople if he deemed they did something wrong.

“Back then, negative motivation was more of a factor than it is now,” Dusty says. “With negative motivation you wanted to say, ‘I’ll show you.’ You can’t use negative motivation today because they’ll quit on you. Everything has to be positive.”

At the Braves’ hotel in Los Angeles, Christine and her son, who was known as “Dusty” because of the dirt he kicked up playing in the fruit fields behind the family home, were introduced to Aaron, the great Braves slugger. The 1967 Braves were a team studded with historical baseball figures in the making such as Joe Torre, Felipe Alou, Cito Gaston, Phil Niekro, Tito Francona, Charley Lau and Bob Uecker. But Aaron, then in his long prime at 33, was baseball royalty. His words were weighty.

“If you believe in yourself,” Aaron told Dusty, “you will be in the big leagues before your college class graduates.”

And then he turned to Christine.

“Mrs. Baker,” he said, “I will take care of him as if he’s my own son.”

Dusty Baker became a baseball lifer that day. When he returned home, he signed with the Braves. His father was so upset about it he sued to have the contract voided. Christine and Johnnie B. Sr. had recently separated.

“We didn’t speak for three years,” Dusty says. “But my mom was my legal guardian, too. They let me have an allotment to buy a car and a school budget, and they put my money [in a stock trust]. I was pissed off. I said, ‘I’m grown now.’

“So, I had to go to court. California was deeded as the trustee over my affairs. They invested my money in IBM and Standard Oil. My money tripled. I thought, Maybe my dad ain’t too bad.”

With the automobile allotment from his bonus, Baker bought himself an Oldsmobile 442 in saffron yellow, a V-8 muscle car with 350 horses.

“Got six tickets in six months and was on assigned risk for the next three years,” he says with that big smile that is as much of his signature as that toothpick.

Fifth inning. ALCS Game 5. Astros lead 1–0. After giving up his first hit, Houston starter Framber Valdez hits J.D. Martinez with a pitch. Baker takes that familiar walk to the mound; he is angular and long-legged. Even at 72, and like the silhouette of his 442, he hints at the speed that once made him a fleet center fielder—before he hurt his knee playing basketball and settled in left field.

Baker is not there to take Valdez out of the game.

“The biggest compliment I ever had from anybody in sports was from Dr. Jack Ramsay,” Baker says.

One day when Baker was managing the Giants, Ramsay, the venerable basketball coach, called the club and said he wanted to meet Baker.

“You know,” Ramsay told him, “you remind me of a basketball coach.”

“What do you mean?” Baker asked.

“I see you go to the mound and it’s like a 20-second timeout.”

Baker swooned over the compliment.

“It’s like what I did with Framber,” he says. “All the action in baseball happens just like in basketball. A team steals the inbounds pass, and then boom-boom-boom all a sudden in 30 seconds they go from five points down to 10 points up. It’s nothing more than when I send my pitching coach to the mound. Because it can happen just like this: boom-boom-boom.”

Seeing Baker, Valdez worried he was there to pull him. Instead, Baker spoke to him in Spanish.

“I know you wanted the no-hitter,” Baker told him. “Then you hit the batter. Don’t let that change what you’re doing.”

Valdez went on to throw eight innings of one-run ball.

Aaron made good on his promise to Christine.

“He did,” Baker says. “He made me get up and go to breakfast. He made me go to church. He gave me discipline. I was blessed. Hank chose me.”

And yet, Aaron could not be there at the start when Baker made minor league stops in places such as Greenwood, S.C., his assignment after his first spring training in 1968. Greenwood was two hours from Orangeburg, where a riot broke out two months before Baker arrived in the area. Black students tried to integrate a whites-only bowling alley, which the owner claimed was exempt from the Civil Rights Act of 1964 because he closed the snack bar in the facility. In what became known as the Orangeburg Massacre, police opened fire on a crowd of about 200 protesters. Three protesters were killed and 28 injured.

In Greenwood, Baker found segregated housing. He roomed with a Black first baseman from Los Angeles, Albert Thompson. They lived and ate at a boarding house, apart from their white teammates.

“A Latin mama took good care of us,” Baker says. “She cooked for us. That’s how it was then.”

One day there was a bang on the door from the fist of a police officer holding a gun. Thompson, Baker says, had been dating the daughter of the local white police chief.

“I knew all he knew about me was I was the same color,” Baker says. “I ran into the bathroom. I hid next to the toilet, so that at that angle he couldn’t shoot me. Thank goodness the mama came out running with a broom and yelling, ‘Thompson ain’t in there! Leave him alone!’ ”

Thompson had been released by the Braves only the previous day.

“The white girl, she ran away to go see Thompson,” Baker says. “When she got there, she found out Thompson was married.”

Baker hit so well in Greenwood that people there called him “The Little Hammer.” Aaron gushed that Baker had more talent than anybody he had seen come through the Braves’ system.

The next year, playing in Shreveport, La., Baker went to dinner with a white teammate, Ted Bashore, and his wife. Ted was paying the bill while Baker and Mrs. Bashore waited on the street outside. A police car drove up.

“Before I knew it the cops had me up against the wall because I was on the street with a white girl,” Baker says. “Ted came out just in time and said, ‘He’s with my wife.’ He saved me.”

ALCS Game 5 again. Sixth inning. Chris Sale reacts angrily after walking the leadoff batter, Jose Altuve, in what is still a 1–0 game. Baker sees an opportunity.

On the next pitch he puts a play on, a run-and-hit. Altuve takes off for second base. The batter, Michael Brantley, has the option to swing at the pitch or let it pass if it’s not in the zone.

“Michael was having trouble seeing the ball against Sale,” Baker explains, knowing that Brantley had struck out in each of his previous two at bats against Sale.

It’s a brilliant play. A hit-and-run would force Brantley to swing at any pitch. The run-and-hit not only gives him the option but also encourages Brantley to shorten his stroke to the ball, knowing the Boston infielders will open a hole as they scramble to cover second because of Altuve’s break for the bag.

Brantley punches a grounder to the left side, where Rafael Devers throws to first. As the throw arrives, Kyle Schwarber is distracted by Altuve, who already has rounded second and is flying toward third. In his haste, Schwarber drops the ball. The Astros have first and third and no outs without the ball leaving the infield. Five runs ensue.

Playing in the Deep South brought Dusty back to his father. Johnnie B. Sr. was born and raised in the Depression in Lakeland, Fla. He grew up amid the injustices his son was facing for the first time. One night, when Dusty’s patience was at its thinnest, when he could not eat with teammates or play pool with them after a game, he spent two hours on the phone with his father. The ice broke.

Dusty played 19 years in the majors and has managed for another 24. He reaches the 2021 World Series with 2,023 hits as a player and 2,025 wins as a manager, postseason included. It is his second trip to the Fall Classic.

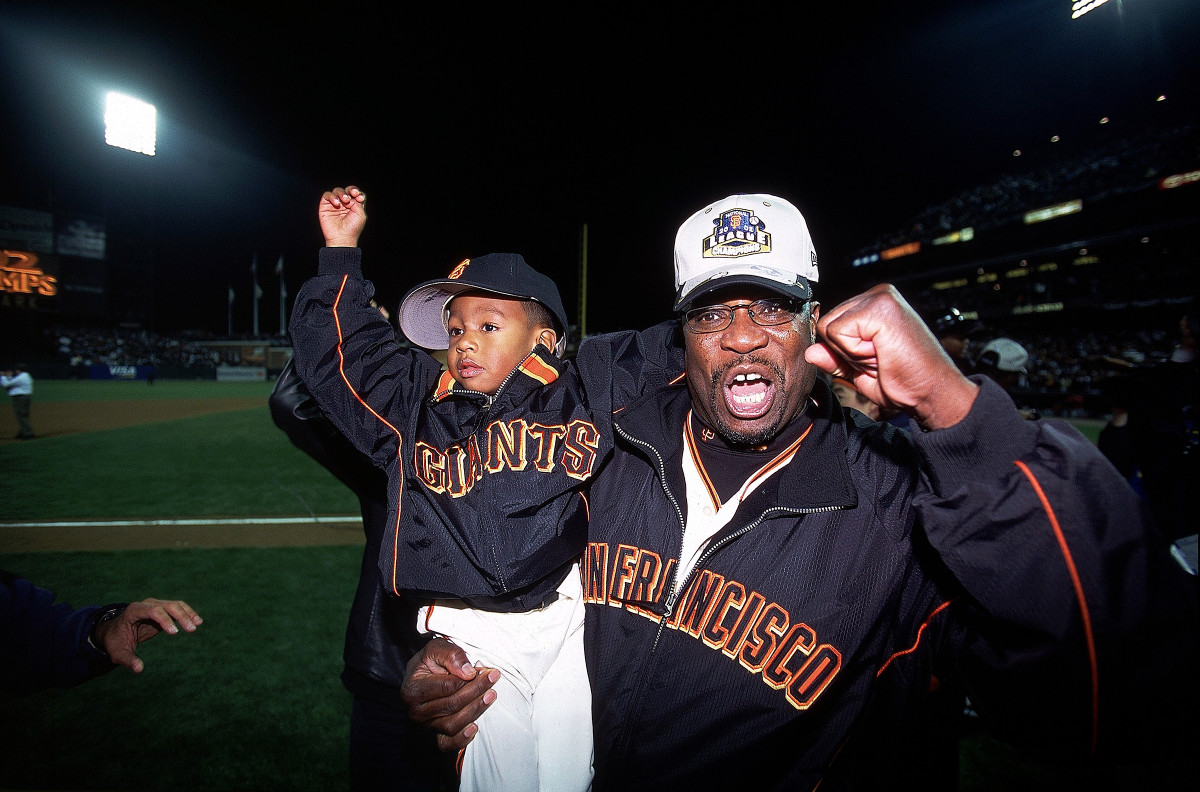

In 2002, Baker came closer to winning the World Series than any manager has without actually winning it. His Giants led the Angels, 5–0, with eight outs to go. No team had ever lost such a big lead in a potential clincher. Baker removed his starting pitcher, Russ Ortiz, with two on and a pitch count of 98. The bullpen crumbled. San Francisco lost, 6–5.

The Giants held the lead again the next night, 1–0, but lost Game 7, 4–1. That night, back at the team hotel, Johnnie B. Sr. told his son, “Man, I don’t know if you’ll ever win one.”

There it was again: negative motivation. The son recognized it.

“That’s his way of motivating,” Dusty says. “I love my dad. He is everything to me. Sometimes as a son some of your motivation is to show your dad that you can.”

Baker is the only manager to take five teams to the playoffs. He has been fired after seasons in which he won 95, 90 and 97 games, each time after playoff defeats that were so agonizing they subsumed the good work he did over six months to get his teams there.

Baker was between jobs in 2007 when his father took ill. Dusty returned to the Sacramento area to be with him, later telling a reporter, “It’s one of the best things I ever did in my life.” His father suffered a stroke in ’08. He died in ’09. (Christine Baker, 90, now lives in an assisted living community in Northern California. She still tunes in to watch her son manage.)

Last season the Astros needed class and decency in the wake of their sign-stealing scandal. They tapped the mother lode of such traits when they hired Baker. He had one request upon taking the job: the back of his uniform, for the first time, would say, “Baker Jr.”

ALCS Game 4. It is the second day of playing three days in a row. Houston starter Zack Greinke gets only four outs and faces nine batters before he is so ineffective Baker must get him out of the game. Baker uses five relief pitchers to get 23 outs and the Astros win, 9–2.

“Perfect example,” Espada says. “He doesn’t overuse anyone. He doesn’t panic. He doesn’t script it. He manages the game with all of his life experiences. We come out of the game with a win and our pitching in good shape.”

Baker has outmaneuvered managers Tony La Russa and Alex Cora this postseason. Now he goes up against Brian Snitker. Somewhere Aaron is smiling. Baker and Snitker, 66, have a combined age of 138. Together they have 70 years of coaching and managing experience in the minors and majors—more than half their lives—without ever winning the World Series. (Snitker was the Single A hitting coach when the Braves won in 1995.)

Watch World Series games online with fuboTV: Start with a 7-day free trial!

Somebody will finally check that box. In the year that began in January with the death of Aaron, it will be a friend of Henry’s who will win this World Series. In 1981, Aaron, then a Braves vice president who ran their farm system for years, called the 25-year-old Snitker to both release him and to tell him he wanted him to become a minor league coach. They were close friends ever since.

Baker said he does not know Snitker well, but they have other mutual close friends. Snitker met his wife on a blind date set up by Cito Gaston, a teammate of Baker’s in his first year in pro ball in Austin. Snitker also is close with Ralph Garr, a former Brave who has worked for the organization as a roving instructor and one of Baker’s dearest friends. Garr was Baker’s first roommate in those Deep South years.

“He came out of Grambling,” Baker says. “He was 22. I was 18. He taught me a lot, [like] certain authoritative figures you don’t talk back to or else it could be detrimental to your health.”

Snitker’s son Troy is the hitting coach for the Astros. During a workout Sunday, Troy teased Baker about what cap Garr will wear in the stands for World Series Game 1. Somebody teased Snitker about what cap his mother and family will be wearing.

“There’s a lot of sorting things out right now,” Troy said.

Baker did exactly what he was hired to do: He moved the Astros forward from the disgrace of the sign-stealing scandal. He did more than that, though. He proved to be an expert tactician at navigating games and people, particularly through the pressure of October. As baseball has turned into a cold, calculating informational war, it is Baker and Snitker, as worn and reliable as a favorite leather jacket, who are the ones that made it to the World Series.

Bashore, Baker’s teammate in Shreveport, earned a Ph.D. in clinical and biological psychology and has been a professor at several colleges. The two have remained close friends. In 1978, Bashore hypnotized Baker to help get him out of a slump.

“I said, ‘Now don’t have me clucking like a chicken or anything,’ ” Baker says. “He gave me a key word: ‘set.’ He got me into the mental side of baseball. He used to tell me, ‘You have one job to do: Get a good pitch and hit it hard. After that, it’s out of your control.’

“I still use it. I tell my pitchers the same thing, like with Framber. ‘Don’t concentrate on the name on the back of the hitter’s jersey. Concentrate on making a good pitch. After that, it’s out of your control.’ ”

Unlike most managers, Baker positions himself on the far end of the dugout when his team is hitting. When asked if it was to better observe his hitters, Baker says, “Yeah, better look at the pitcher and the hitters. It’s supposed to make [opponents] nervous. I’ve been asked a couple of times, ‘Why are you always hanging out at that end? Are you stealing signs?’ ”

His tactics this postseason have been spot on, especially surviving only 21 innings from his starters in six ALCS games. In many ways, informed by voluminous life experiences, Baker is better at managing than ever before.

“It’s a combination of observing other games, knowing yourself and trying to stay modern on how the game is played and how the players expect the game to be played,” Baker says. “You know, when I took Russ Ortiz out in that game, today that would have been the move to make. But then it was, ‘Why’d you take him out so early?’ So who knows? Maybe I was ahead of my time, which I have been for most of my life.”

Sign up to get the Five-Tool Newsletter in your inbox every day during the World Series.

Baker is a music enthusiast, a God-fearing man, a winemaker and an avid fisherman. He is defined by so much more than managing, but his managing is defined by having won more games without winning the World Series than anyone in history. The man who has so much is defined by absence, particularly with how close he has come to checking that last box.

“You have to take advantage of every opportunity,” he says when asked what he has learned from the close calls. “Because it’s just like fishing and hunting. They’re going to make one more run. When the fish sees the boat, he’s going to do everything he can to stay in that water, you know what I mean? That’s what these games are like.

“In every game, they’re going to make one more run in the seventh, eighth or ninth. I don’t care what the score is. Almost every game. So, you really have to bear down.”

It took Baker 19 years to get back to the World Series, the longest wait for a return engagement except for the 22-year hiatus for Bucky Harris, though Harris was a 28-year-old player manager for the 1925 Senators on his first trip. Baker is going back this time without Aaron and without his father, at least in the physical realm.

“Sometimes when I don’t know what to do, I’ll ask my dad,” Baker says. “If I see him smiling, I’ll do it. If I don’t see him [with] an expression, I won’t do it.”

Aaron fulfilled his promise to Christine. He became Dusty’s father in baseball. He launched this big baseball life and the lessons of discipline to withstand its many difficulties. On Aug. 1, 1982, Aaron was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame. Humble Henry had difficulty believing he was standing in the very footsteps of Jackie Robinson and Roy Campanella.

“A man’s ability,” Aaron said in his speech, “is limited only by his lack of opportunity.”

That night, in tribute, Baker hit two home runs for the Dodgers. Against the Braves. In Atlanta. The first, which proved the game-winner in the seventh inning, nearly smacked against the sign in left field commemorating Aaron’s 715th home run.

Baker was on deck when Aaron hit that home run to supplant Babe Ruth as the home run leader. Baker did not rush to the plate to greet him.

“It was his moment,” Baker explains. “That’s just how I was raised.”

The 117th World Series is Dusty Baker’s moment as much as it belongs to anyone. Even without his two paterfamiliases for the first time in October, he is not alone. Never more than now is he Johnnie B.’s son and the Hammer’s protégé.

More MLB Coverage:

• World Series Predictions: Who will it be, Houston or Atlanta?

• 'Hell No. We're Doing It Tonight': How Atlanta's Season Shifted

• Tyler Matzek's Improbable Journey to Immortality in Atlanta

• Pearls Before Swing: Meet the Man Behind the Joctober Bling

Read more of SI's Daily Cover stories here

Sports Illustrated may receive compensation for some links to products and services on this website.