In the Shadow of Tom Brady: What It Means to Be Pick 199

One random Halloween afternoon a million years ago, two forgettable Big Ten football programs clashed in Minneapolis. The 15–10 barnburner would all but vanish from memory, lost to the far reaches of football history—except to one Minnesota lineman, Adam Haayer, and Michigan’s starting quarterback, Thomas Edward Patrick Brady Jr. Eventually, two football players who held nothing in common would be joined by one number: 199. As in, 199th overall, their shared NFL draft slot.

Haayer (199, ’01) watched the festivities in 2000, his attention lingering on Big Ten prospects, like Brady, whom the Patriots famously selected in Round 6. “I was actually surprised he got drafted,” Haayer admits. The tackle would be stupefied later, when he realized his 199 status one year later would forever tie him to the GOAT. He still tells youth football campers about their connection, still roots for Brady, his teammate in a fraternity as strange as any in sports.

On Saturday, the brotherhood will welcome another member when the Vikings, barring a trade, will tie one hopeful to a legend and everyone who followed him at 199. The pick will represent a gamble, same as always, the choice split between small schoolers who faced inferior competition, major-program prospects who tested poorly or bloomed late, fliers who switched positions or projected elsewhere in the pros and quarterbacks who see Brady as a blueprint, despite the impossible nature of his miraculous career path.

Haayer’s life, like most players drafted in the slot the quarterback made prominent, is the one that Brady could have lived. It’s the difference between 20 career NFL games played and 21 glorious NFL seasons starred in. Haayer’s LinkedIn profile is proof:

NFL Football Player, April 2001–Jan 2007

New and Used Car Sales Consultant, Jan 2007–Jan 2008

Sales and Marketing, Rollx Vans, Jan 2009–Sept 2015

Haayer skipped hosting a draft party, given his limbo-low expectations. Good thing, because the Titans took him during a commercial break while he sat in his parents’ living room. He set a modest goal that night, wanting only to make the team. Before he could, he blew out a knee in camp. He bounced to Minnesota, Arizona, St. Louis. He learned how to play guard and center, trying to push back his football expiration date. Still, he jokes, “I had a really good career of getting fired.”

John Madden didn’t help. Haayer met the broadcast icon before a Monday Night Football game against Philadelphia, and he reminded Madden of their shared birthplace: Austin, Minn. That night, Haayer replaced an injured starter and was tasked with blocking Jevon Kearse, a pass rusher whose nickname—The Freak—spoke to his genetic fortune. Haayer terms his performance “not horrible,” noting that he did not yield a sack. But there was Madden, telling the world, “Well, if this Haayer guy doesn’t pick it up, he’s gonna be for-hire tomorrow.”

And, later: Man, this Haayer kid is having a tough go. I’m almost embarrassed to say I’m from the same hometown as him.

Haayer hung on, like most 199s, for as long as he could. He fought through injuries, requiring roughly 20 epidurals so he could stand up straight and block. He made $120,000 his first year. He lived in a friend’s basement to save money, the bed next to a beer fridge, the bottles rattling at night. He also loved every minute of this outlier existence, the chance to simply play pro football, regardless of what it would cost him.

Extensive damage to his back left Haayer unable to work in 2015. He quit his job hawking wheelchair accessible vans and went on disability, sold his house and downsized. He moved from Minnesota, where the cold worsened his injuries, to Texas. He can’t stand up for long stretches, can’t sit in a non-supported chair, and can’t walk without limping, due to nerve damage in his right leg. A golf cart ferries him even short distances, and he reads more, because he can’t move much. Only naps provide brief respites from pain. “It’s pretty miserable, to tell you the truth,” he says. His goals changed. “Right now, I want to keep myself busy, healthy and positive.”

All these years later, Haayer understands that 199 life, how sharing a celebrated draft slot with Brady ruined all reasonable expectations. But rather than see Tom Terrific’s success as an impossible hurdle, he looks to Brady for the same things as the rest of their fraternity: motivation, inspiration and, above all, hope.

Pick No. 199 in the draft was just another number on that now historic Sunday in April, 21 years and 13 days ago. Even some New England staffers from that time are careful not to retroactively claim an unfair share of responsibility for the franchise-altering selection. Charlie Weis defers to Scott Pioli, then the Patriots’ assistant director of player personnel. “Too many people want credit on this one!” Weis quips. And Jason Licht, who two decades later brought Brady (and, subsequently, a ring) to Tampa Bay, distances himself from the QB’s original drafting. “I did not scout Brady,” asserts Licht, then a southeast area scout.

No bigger proponent of Brady emerged than Dick Rehbein, the Patriots quarterbacks coach who would die of heart failure during training camp the following year. He saw the potential in the mildly unathletic Michigan prospect despite the two Drews in the way: Henson, with whom Brady had been mired in a platoon in Ann Arbor, and Bledsoe, who would sign the largest contract in NFL history with New England a year later. Licht, again making clear he had no hand in Brady’s selection, recalls the moment when Bill Belichick and Pioli turned in Brady’s name as relatively unremarkable.

“Quarterback wasn’t really a dire need for us,” Licht says. “But if it had been a dire need for us, I believe he would have been taken a lot higher than he was by Bill.”

That number, 199, would help define Brady’s ethos. But what no one could have expected at the time was the invisible string that would connect those that followed in that draft slot. Like the player drafted No. 199 a full two decades later, whom Brady would face on a Monday night last November. The morning Rams rookie safety Jordan Fuller (199, ’20) would play the GOAT for the first time, his sports psychologist reminded him via text: “Pick 199 vs. Pick 199.”

They’d talked about Brady even before Fuller joined the 199 club. In the months before the 2020 draft, Fuller began working with Donovan Martin, a Fort Wayne–based sports psychologist. Martin held up Brady’s mental strength as a model, specifically his ability to lock in under pressure, using the adrenaline of big moments to elevate his performance without being paralyzed by stress. “It was funny that I was drafted in the same exact spot as him,” Fuller says.

Like Brady, Fuller was a big-school player—from rival Ohio State—whose measurables played a role in his 199 availability. He was clocked at 4.67 seconds in the 40-yard dash at the NFL combine, and the COVID-19 pandemic prevented him from running again at the canceled Buckeyes’ pro day. But also like Brady, he had an advocate in his future team’s draft room: For Fuller, it was Midwest area scout Brian Hill, who told decision makers, roughly, Draft him. Don’t think twice. Thank me later.

Thus Fuller, who started immediately for L.A., came to stare across the line at Brady in Tampa last November. Halfway through the third quarter, with the score tied, Fuller played a deep zone by “reading Tom’s eyes.” Under pressure, Brady underthrew a post route to Chris Godwin. Fuller used his body to secure the turnover, grabbing both his first interception and a piece of 199 history. Then, just inside of the two-minute warning, with the Rams leading by three, Fuller encountered the exact situation he’d prepared for with his sports psychologist, by studying Brady. He tracked the ball again in a deep zone, to snatch the overthrown pass to Cameron Brate. Game over. “It was a bunch of mental work coming to fruition, playing him,” Fuller says.

He returned to his locker to find text messages from Donovan praising his “serious mental strength” and reminding him there are “no limits.” Even more memorable: the message Fuller received a few days later, an Instagram DM from the player who made their draft slot famous. Fuller is nervous at first about sharing a private message from Brady, but it’s perfectly relevant. “Congrats, 199,” Brady wrote to him, per Fuller. “I’m not gonna let that happen again.”

Their message exchange, Fuller says, was “a good little initiation” into the 199 brotherhood—not that he didn't know the significance of his first interception as soon as it happened. Miked up by NFL Films that night, he looked into a sideline camera after that play and announced: “I was drafted 199, too! Don’t forget that.”

THE SMALL-SCHOOLER: ADRIAN PETERSON (’02)

Early 199ers didn’t know Brady as greatest-of-all-time Tom Brady, meaning they saw their draft slot less as a shared oddity and more as their only NFL chance. For those from lower college football divisions, like Adrian Peterson—and, no, not that Adrian Peterson—that’s as much as they could reasonably hope for, a sliver of opportunity to wiggle through.

Peterson watched the draft with his parents, and even though he expected to go earlier—a common theme for the 199s—seeing his name scroll across the ticker marked a “thrill.” As a tailback for Georgia Southern who ran a 4.69 40-yard dash at the combine, Peterson knew that teams eyed him warily, despite 9,161 career rushing yards, the tally staggering enough to land him in the College Football Hall of Fame.

At Bears training camp, Peterson made the team through his prowess as a return specialist. Each subsequent year, he gained more responsibility. In 2005, after injuries sidelined the backs in front of him, Peterson became the starter, scoring against the Panthers in the Divisional playoff round. The next year, his forced fumble in the NFC championship game helped send Chicago to the Super Bowl, where the Bears lost to the Colts. This wasn’t exactly Brady’s story, but it wasn’t too far off: underdog overcomes draft slight to become key member of team that plays for NFL title—the route of 199er dreams.

Peterson held on, too, for as long as he could. He thought he could make the Seahawks roster in 2010 but was released so Seattle could add a second kicker. He latched on with the Virginia Destroyers, winning a title, just like Brady, only the United Football League version. He wrote a book, Don’t Dis My Abilities, detailing how he overcame a speech impediment, and the volume led to motivational speaking gigs after he retired.

He also endured tragedy; his seven-year-old son died of a brain tumor. He pushed through everything. “Just strength, man,” he says.

Eventually, Peterson returned to his alma mater. He won’t spend his post-football life espousing recovery techniques like the quarterback who turned his number and career longevity into the TB12 Method. Instead, he works in development for athletes at the university, telling both his story and Brady’s to inspire batch after batch of overachievers—just like them.

THE BIG-PROGRAM QUESTION MARK: THEO RIDDICK (’13)

When Theo Riddick was selected by the Lions, he didn’t think of Brady at first. Like the others in the 199 fraternity, his drafting was bittersweet, as he considered the long odds he’d face as a sixth-round pick: A “crab-in-a-bucket type of lifestyle,” he calls it.

If you’ve ever literally put crabs in a bucket, Riddick explains, the first thing they try to do is get out. But when one starts to make progress, the next crab will pull them back down. He views late-round picks as crabs all dropped into the same bucket. “You're in the midst of a lot of players willing to do anything to not have you gain that roster spot,” he says.

Before heading to Detroit, Riddick sought inspiration for how to navigate this uncertain path. A few friends had mentioned 199 was Brady’s slot, too. Just like Haayer, who still watches YouTube videos of draft “experts” certain in their collective belief that Brady would never last in the NFL, Riddick started searching for the knocks issued on Brady in 2000: Skinny guy. Pretty slow. Didn’t have the tangibles to be a top-tier quarterback. “That's how I got my perspective on it,” he says. “Because then you get to see, when he rolled the dice, what did he get? He got f---ing six rings.” (Seven, actually, but it’s easy to lose count).

Riddick expected to be a third- or fourth-round pick, and during the draft he became another 199er led on by empty assurances from teams telling him to remain on alert. Looking back, he figures he lasted that long because he “wasn’t on the scene as much,” bouncing around positions before breaking through at running back his senior year, when Notre Dame went undefeated in the regular season. He then pulled his hamstring right before the combine and had a severe shoulder sprain that didn’t allow him to perform the bench press.

He can’t count the number of times he needed “that hope” he derived from Brady. Here’s one: Heading into his third season, the Lions’ depth chart at running back was getting crowded. The team had drafted Ameer Abdullah in the second round, and Riddick says Detroit’s special teams coach at the time, Joe Marciano, told him there were conversations about not dressing him for the season opener. He ended up having one of the most productive seasons of his career, joining teammates Calvin Johnson and Golden Tate in one of only five trios in NFL history each with 80 or more catches.

Riddick, who just re-signed with the Raiders, is one of the best-known 199ers after Brady (and certainly the most fantasy football relevant). He recalls the GOAT himself telling him after a 2018 game in Detroit, “I love what you do.” But Riddick still bristles at the idea of a 199 fraternity. As a crab that made it out of the bucket, he’s worked for nine years not to be defined by his draft status.

“I feel like I still get the respect of a sixth-rounder. And I feel like I’m worth more than that, to be honest with you,” he says. “I do feel that in this league, no matter how successful you are, you get treated depending on the round you got drafted.

“Unless you're Tom Brady.”

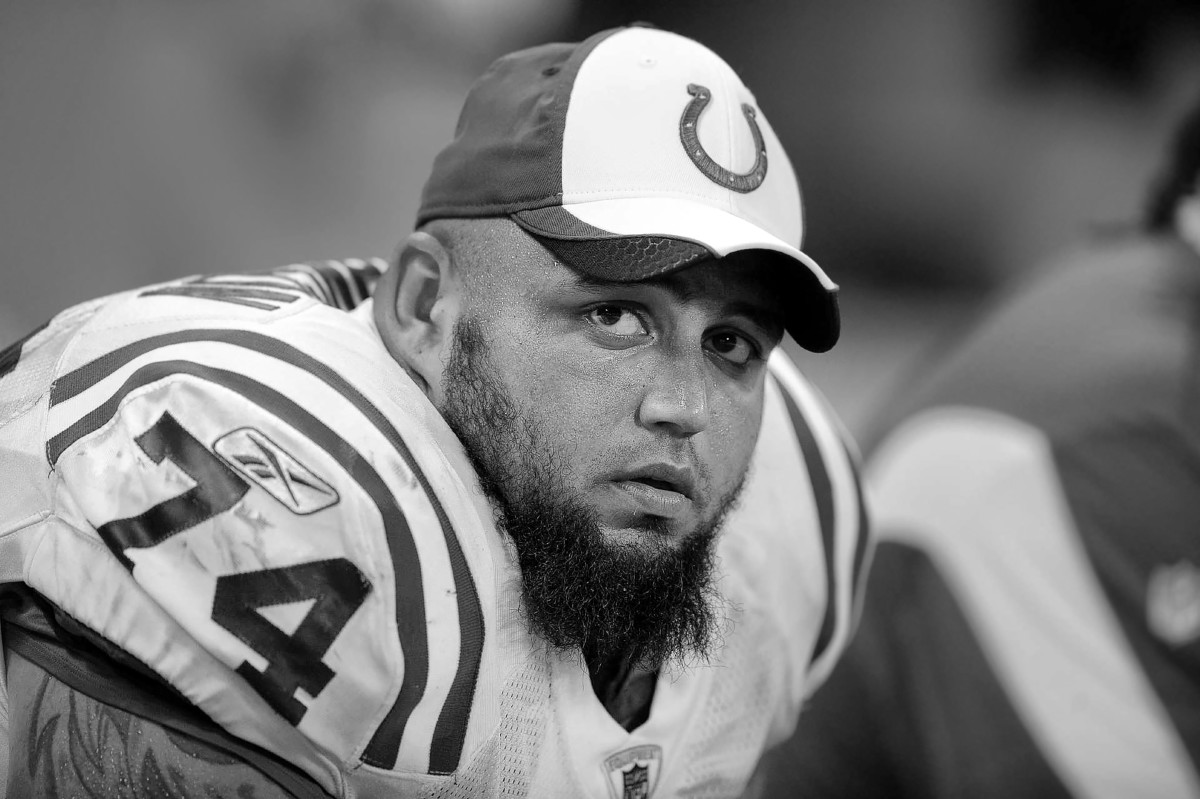

THE FLIER: CHARLIE JOHNSON (’06)

The speculative bets selected 199th overall can only envy Riddick’s pedigree, the Notre Dame influence on draft slots. They’re not typically role players or late bloomers for college powers, but rather prospects who were forced to switch positions, either in school or afterward; their potential seen in what they might do, rather than bolstered by their resumés.

They’re players like Charlie Johnson, a tight end at Oklahoma State who converted to the offensive line before his senior season, leaving him little time to learn a new position, let alone wow scouts with game film. On the day his college career ended, Johnson guessed his football days were over, too. And that point would be driven home by one terrible draft visit.

The appointment in question was in Indianapolis, the final and by far the worst of Johnson’s four trips to NFL facilities. It took place the weekend before Easter, inside a Colts facility devoid of decision makers. Where other teams at least feigned interest, with fancy dinners and high-level meetings, Johnson noted the absence of coach Tony Dungy, the brief meeting with general manager Bill Polian and how an intern retrieved him at the airport. This intern even forgot to hand over Johnson’s per diem money, and rather than descend on a steakhouse, he ordered Chinese takeout from a nearby restaurant and paid his own tab.

Imagine his surprise, then, when Polian and Dungy called to inform Johnson he would be a Colt. Maybe I have a chance, he reasoned, against logic, just like Brady had. After all, the quarterback that every team passed on for five rounds had already won three Super Bowl rings from their shared draft position, raising the possibilities, even the deluded ones. “He gave guys like me that hope that we can make it,” Johnson says. He pauses, recognizing the need to clarify. “Obviously, you’re not going to turn into Tom Brady,” he chuckles.

Johnson made $275,000 his rookie season, the same year Brady passed $14 million in salary for the first time. The newbie sought input from the veterans around him, just like Brady, leaning on Pro Bowl lineman Jeff Saturday, once an undrafted center who landed on the waiver wire before he stuck. Saturday taught Johnson how to approach football—less like a job and more like a craft. He didn’t need to chug gallons of electrolyte water and disgrace linemen everywhere by switching to avocado ice cream. He didn’t need to be Brady to arrive at a similar mindset.

Nine seasons, two franchises and 134 games played later, Johnson had not exactly elevated into Brady’s stratosphere. But he came the closest of any 199er since ’00 to Brady’s longevity.

For five seasons in Indy, Johnson also became, if not necessarily Brady’s rival, then at least a significant part of the budding hatred between the Colts and Patriots. In that ’06 season, he helped Indianapolis topple New England in the AFC championship. He can still remember the tiniest details: the halftime deficit; the speech from Dungy, “Guys, we’re gonna win this game”; the acrobatic Reggie Wayne catch; the Marlin Jackson interception to seal a Super Bowl bid. For the rest of his career, Johnson would never hear a stadium so loud. The Colts would win Super Bowl XLI, with Johnson subbing in again for the last two and a half quarters. At one point quarterback Peyton Manning glanced at the rookie lineman in the huddle, winked and said, “How long have you been in here?”

Long enough. That night, Johnson became the only 199er since Brady to win an NFL title—at Brady’s expense, no less. In that moment, however brief, Johnson knew how it felt to live Brady’s charmed life, and what it took to get there. “It’s crazy that I’m somewhat associated with him,” Johnson says. Now a high school football coach in Stillwater, he keeps his ring in a lockbox in his closet. He wears it once a year, and only once a year, on the Sunday of the Super Bowl. The mind-boggling part: Brady is still playing in most of them.

THE OUTLIER: GARRETT SCOTT (’14)

Some 199ers defy easy categorization, their lives—and careers—changed by circumstances beyond anyone’s control. Like Garrett Scott. An unusually athletic offensive tackle at Marshall, he presented as an archetypal Seahawks pick, settling far enough off the radar that he wasn’t invited to the combine, but firmly on the radar of scouts. He was drafted the same weekend that he earned his college degree, fielding the phone call from Seahawks execs John Schneider and Pete Carroll in the hallway of a banquet hall where his family had gathered to celebrate the dual occasions. His god brother, immediately noticing the pick number, told Scott he hoped there would be a “Mr. 199” party so he could meet Brady.

Before Scott could even participate in rookie minicamp, though, the Seahawks pulled him off the field. Since he hadn’t gone to the combine or visited Seattle pre-draft, the physical he took before signing was the team’s first extensive medical evaluation of him. One form asked if any family members had passed away of a heart condition, and Scott answered yes: He was a third-grader when his older brother, Randolph Scott, Jr., collapsed during gym class. The team sent Scott for tests on his heart as a precaution, including an EKG and MRI with contrast.

The results were startling: The scans showed a condition called hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, in which the walls of the heart become abnormally thick, making it harder for the heart to pump blood throughout the body. Scott was confused; he never had any symptoms, nor had this shown up in the physicals he’d taken in college. But the risk of heart failure this condition carries can be exacerbated through extreme physical exertion, meaning he would be sidelined indefinitely.

Even seven years later, Scott recalls vividly “the day I got my heart crushed.” He walked into the training room before the team left for its first preseason game and was told three doctors wanted to meet with him. He’d continued to get heart scans, still hopeful he could play again, but the doctors told him that day the risk was too great to continue the NFL dream he’d first written on a football as a kindergartener. “I was in that room, crying for a little while,” Scott says. Teammates James Carpenter and Alvin Bailey engulfed him in hugs. He also spent a while talking to Russell Okung about his next steps in life. “He told me, ‘Invest in Bitcoin,’ ” Scott says.

Scott couldn’t help but feel like damaged goods. But the Seahawks supported him, choosing to sign him to his rookie contract before waiving him, so he could earn the approximately $100,000 signing bonus slotted for pick No. 199. They also paid Scott salary and benefits during the 2014 season, which he spent with the defending champs, attending every meeting, learning game plans and taking mental reps on the sidelines. He says he hasn’t needed medicine or surgery, and doctors were never able to tell him what caused the condition—only that it wasn’t hereditary.

The sudden transition was not easy for a player the Seahawks once thought could grow into a starting left tackle. Other NFL and CFL teams checked in with Scott’s agent, but his medical file was a deal-breaker. He began binge-eating as a way of coping, his weight ticking above 350 pounds by the one-year mark of his draft day. Before a springtime trip to Lake Washington in 2015, Scott looked in the mirror and got a wake-up call. He began walking, then running, then returning to the gym and eating clean, eventually losing more than 80 pounds.

“I had some moments where I felt like I wasn't worth anything just because I didn't play anymore,” Scott says. “It took a while [before] I realized that didn't make sense at all.”

Scott remembers Okung inviting him and other rookies to various business events during his year with the team, and he realizes now the veteran was trying to show him a world outside football. Scott has tried to do the same for former teammates who are facing their own transitions out of the game. Losing football, he says, “made things a little bit simpler.” He still lives near Seattle, in Bellevue, and makes hip-hop music under the name G Swervo. People often ask him if he’ll record a track about having to leave the game behind, but he says he just wants to put out good vibes. He wants to be “the most positive 199.”

That Mr. 199 party Scott’s god-brother was hoping for has not happened yet, though Scott’s path has tangibly intersected with Brady: He passed him on the field after Super Bowl XLIX, moments after the Patriots snatched the trophy from Seattle at the one-yard line. He didn’t stop Brady because, well, you know. But there was something fulfilling about being there that season, ending up on the same field as his fellow 199.

“In a sense, I feel like I did accomplish my dream,” Scott says. “I got there.”

THE LONGSHOT QB: LUKE FALK (’18)

The QB 199ers came to identify more closely with Brady, naturally, than other players chosen there. Even as the years flew by and the titles accumulated, making him even less like them. Still, they play the same position and share the same draft slot, which is enough for players like Luke Falk to hold onto.

The sentiment isn’t all that unreasonable: Brady threw for 4,773 yards and 30 touchdowns in college; Falk, an All–Pac-12 selection at Washington State, nearly matched the yardage total and exceeded the touchdown tally in ’15 alone. Even after accounting for Falk’s more open offense, how passing exploded over Brady’s career and the rules changed to limit defenses, the statistical difference speaks to hope that can, at least, be shared. Not even Brady could have foreseen what he would become.

When the Titans—and former Brady teammate Mike Vrabel, their coach—took Falk, the QB wore, of all hats, a TB12-branded one. (He had visited the center after his senior year to rehab college injuries.) Falk told his coaches one vivid football memory: watching the Tuck Rule Game, when Brady beat the Raiders on a controversial overturned fumble to advance to his first conference championship. Falk was seven, watching on TV.

Falk’s pro football odyssey started that day, all those years later, with the depth, breadth and possibility of Brady’s career looming like an idealized version of reality. Falk would be cut (Titans), claimed (Dolphins), placed on injured reserve with a wrist injury and released after Miami traded for Josh Rosen. He would be claimed, yet again, by the Jets.

In September 2019, Gang Green elevated Falk from its practice squad. Due to illness (Sam Darnold, mono) and injury (Trevor Siemian, broken ankle), Falk began his NFL career just like Brady, only this time for the Jets, rather than against them. The football gods leaned into the juxtaposition, as Falk’s first start took place in Foxborough, against you-know-who. This birthed comparisons, many unfair, until Falk replacing a sick starter morphed into the same thing as Brady replacing a hobbled one. That Brady's first start also came against a legend—in his case, Manning, then with the Colts—added symmetry. Playing against Brady, Falk says, “is the only time I’ve ever cheered against him.”

Brady toppled the Jets easily, same as throughout two dynastic decades ruling the AFC East. Falk struggled on the same field as his idol, who found him afterward and told him to “hold your head up” and “keep pushing.” Darnold came back soon after, and Falk played only once more in ’19, taking nine sacks against the Eagles in a game when he tore both labrums, leading to his midseason release.

Still, he cannot let go, not with Brady as the benchmark. “It’s hell and heaven at the same time,” Falk says. “You put your body through everything. But there’s no rush like running out of that tunnel. It’s like a drug.”

With another NFL draft on the horizon, Falk signed instead with the Saskatchewan Roughriders of the CFL. His May start date was pushed to August recently, due to pandemic restrictions at the border. But if the whole football thing doesn’t work out, he has another idea: start a Pick 199 group on Facebook. Brady would be his first invite.

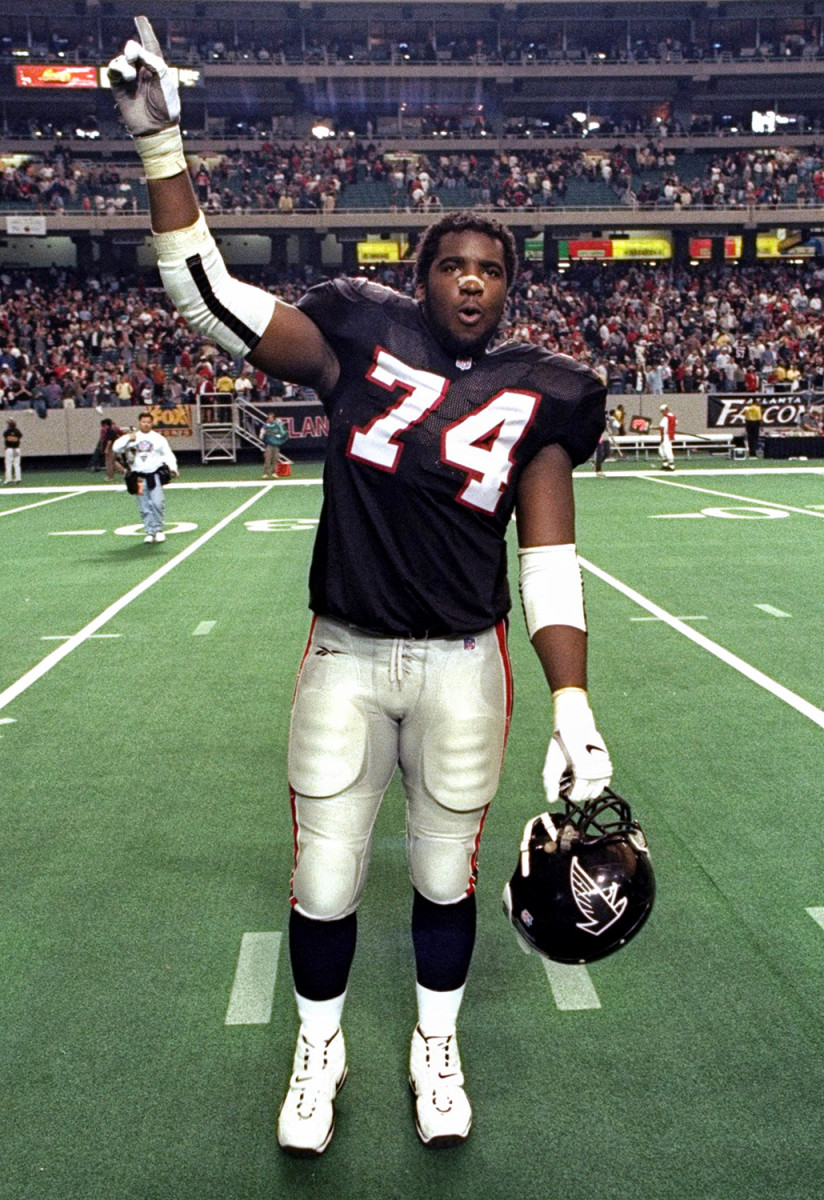

THE OG: EPHRAIM SALAAM (’98)

After Ephraim Salaam played one season with the Falcons—and lost Super Bowl XXXIII—he considered his job secure enough to allow for one splurge. So he bought a silver Mercedes-Benz, and he knew exactly how to personalize the license plate: Pick 199.

Two years before Brady transformed their draft slot into the number that most motivated him, Salaam knew his life would be defined by the same three digits. He’s an OG 199er, a founding member. He knew that as the draft unfolded, when his agent rented out a restaurant in San Diego and Salaam invited everyone he knew. As confidants snacked on appetizers and downed drinks, he told them all he would be drafted by the Jets, a team with a local scout Salaam had grown close to. “We’ll take you in the third round,” the scout promised, even, Salaam says, that very morning. They didn’t.

He can’t remember who strolled to the podium to announce the team’s fourth-round pick. He can remember that it started out something like: and with the 111th pick in the 1998 NFL Draft, the New York Jets select …” He’ll never forget. Jason Fabini.

“My soul just slunk out of my body,” Salaam says.

Party, over. Salaam drowned his sorrow in nachos. When the wait continued the next day, he could no longer watch. While driving to a movie theater, he fielded several phone calls from executives expressing interest in him as a free agent. So when Art Shell buzzed in, Salaam was over all of it. When Shell introduced himself, Salaam answered, only, “Yeah.” But Shell told him he had been arguing for Salaam’s selection since Round 5. The Falcons, Shell emphasized, had an opening at right tackle. “Whatever happened, once you get here, it’s up to you,” Shell told him.

Salaam hung up, turned to his brother and said, “I’mma make everybody pay.”

Football became his sole focus, his vision tunneled by revenge. Sometimes, he looks back at pictures of himself from that season and sees the hair, wild and grown long; the clothes, chosen haphazardly; and those eyes, so piercing and focused. His appearance shows Salaam the ignore-all-else devotion necessary to prove to 31 teams how badly they had missed. He’s exactly like Brady, a Hall of Fame–caliber grudge-holder, in that regard; 199ers at their core.

Salaam managed to play 13 seasons, wear five different jerseys, start 129 games and play in 163 total. He excelled, becoming a Pro Bowl alternate at a position with nods hogged by future Hall of Famers. Like Brady, he played forever and played well. Over time, he came to see the quarterback as a beacon, the torch bearer. “I was just happy [with] the light he showed,” Salaam says.

Salaam believes the 199s deserve their own fraternity. Not like the “Mr. Irrelevant” players, chosen each year with the last pick in the draft. More like “Mr. I’m Relevant” instead. Salaam would establish ground rules that determine standing: five seasons played for membership, with bonuses for longevity, championships or accolades. Start 100 games and you’re eligible for a board seat. This could be Brady’s new team in retirement, whenever that comes, in one year or another five.

These days, Salaam continues his post-football transition to Hollywood, more proof that he and Brady aren’t so different, after all. For a 199er who now thinks in story, a recent contestant on Wheel of Fortune and a producer who helped found Hidden Empire Film Group, Salaam loves how 199 ties so many disparate prospects together—and how the 199 from 2000 transformed a late pick into a rallying cry. It’s the poetic kind of arc.

“Everything I do, I live as though I’m the 199th pick,” Salaam says. “That’s how much energy and effort I put into everything.” His words would apply to Peterson, to Riddick, to Johnson and the rest, Brady (199, ’00) included. Perhaps Salaam could open a film on 199ers that way. Regardless, he knows one thing: He won’t be able to write a more improbable script.

More SI Daily Covers:

• Meet Prospect X, the Draft's Deepest Sleeper

• Trey Lance Is Just Different

• Alex Smith Healed Enough to Walk Away

• Trevor Lawrence Is Out to Prove Absolutely Nothing