Xavien Howard’s 10 Picks: The Perfection of His Craft

Xavien Howard’s run toward superstardom continued in the Dolphins’ season opener last week. Miami was at New England, protecting a one-point lead in the first game of a season of heightened expectations.

Tua Tagovailoa had thrown a fourth-quarter interception at mid-field, the kind of errant pass that leads to losses, particularly against Bill Belichick’s team. The Patriots drove down the field, set up with a first-and-10 at Miami’s 11-yard-line, the clock ticking under four minutes. A go-ahead—and likely game-winning—field goal seemed but a mere formality at that point, at least until Howard did what Howard does best.

The ball was snapped with 3:35 remaining on the game clock. The Patriots had dialed up a Damien Harris run, sending the back off the right tackle, toward Howard’s side of the field. Harris picked up his 99th and 100th yards of the afternoon, only to find one of the best and most complete cornerbacks in pro football waiting for him.

Howard managed to place his left hand on the ball. Harris leaned forward, hoping to gain additional yards, only for Howard to rip the ball loose. As Howard hit the ground, so did the ball—he gathered it in as teammates piled on top of him. Minutes later Jacoby Brissett’s QB sneak converted a game-clinching first down.

The Dolphins won, 17–16. But this play, this game and this win spoke as much to a cornerback’s evolution as to his team’s growth. In fact, Howard has turned his craft into something of an art form, one illuminated by 10 interceptions from his 2020 season. This is the story of his rise, told through the prism of those picks and everything that came before them.

Howard has a first-world problem known only to the best defensive backs in professional football. Only the first-team All-Pros, the generational talents, would understand. There’s space reserved at his home in south Florida, inside his self-described “man cave,” nearby a kitchen-table-sized flatscreen and the jerseys hanging on the wall, for an exhibit. The one he wants to create.

This den is at once an escape from the NFL and a celebration of Howard’s place in it. In an ideal world, he would display every football that he has grabbed, snagged, picked, seized and intercepted in five-plus seasons, all spent in Miami, starring for the Dolphins. And that’s where his good-problem-to-have starts: there are too many footballs. They’re all over the place, like cocktail glasses left behind after one hell of a party. Some are encased in glass. Some are stacked. Some are signed. And each ball tells two stories at once: of a particular moment in a particular game in Howard’s now 22-interception career—and, collectively, of a larger story, grounded in one particular and especially difficult art.

Before the 2020 season started, Howard knew exactly how many picks he wanted to add to his collection. Not only did he know, but he wrote the number down, on his goals list, which he taped to the mirror in his bathroom so that his ambitions would be among the first things he saw when he got up. There were several categories: first-team All-Pro, make the playoffs, play in the Super Bowl, defensive touchdowns. Next to INTERCEPTIONS he wrote “10.” Never mind that he had never recorded that many turnovers in any one season, not in high school, not in college and not even in 2018 when he led the NFL with seven picks but played only 12 games.

Every morning, when Howard washed his face, he looked into that mirror, at that goals list, and considered what 10 interceptions could mean. For him. For the Dolphins. For the new contract he was seeking from team brass. Gazing from the list to his reflection in the mirror, Howard said things like, “Man, you can cover anything you put your mind to.”

He even spoke to himself like an elite cornerback, the kind who had turned backpedaling, jostling for position, sprinting and leaping and acrobat-ing, plus grappling with NFL rule changes that favor offenses, into an artform. Those footballs that left the hands of opposing signal callers and landed in his own, they were his canvas, his avenue toward glory, self-expression, more millions and, maybe, in a perfect, faraway world, the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

At that point, he just needed those 10 interceptions to vault himself toward the next phase of his career. That’s all.

Howard’s quest did not begin exactly as expected. Miami fell to New England and Buffalo to start the season, Howard failing to record a pick in either game. The list on that mirror began to taunt him every morning.

Pick 1: In Week 3, the Dolphins travel to Jacksonville. One of Howard’s coaches feels it necessary to remind him of the fickle nature of the interception gods—picks tend to come in bunches. They seem to result from the totality of the factors involved, the marriage of athleticism, film study and knowledge of scheme combined with opportunity. They cannot be forced. Cannot be paid for.

Fourth quarter. Dolphins up, 31–13. Howard remains in the game as the Jaguars mount a final drive. On one play, quarterback Gardner Minshew drops back and notices a blown assignment in Miami’s secondary. The nickel corner can’t quite catch up with wideout Chris Conley, who’s streaking up the left side of the field. Howard ends up trying to cover for his teammate, guarding two players at once, sneaking over to try and break the pass up. He thinks he has deflected the football. He’s wrong; it goes for an 18-yard completion. “I was mad,” Howard says. “I thought he dropped it.”

This play speaks to the art of playing corner, in how little the fans in the stands or the friends huddled around a television understand the myriad complex machinations of defensive football. Some will say Howard had been beaten on that play. But he had almost helped Miami overcome another player’s mistake instead.

Even then, his instincts tell Howard something. To be ready for Minshew to go back to Conley on the very next play. This happens. Minshew tosses up a fade. Howard leaps and grabs the ball near his own end zone.

One measly turnover at the end of a blowout victory meant far more to Howard than anyone else. He found fellow corner Bobby McCain on the sideline and reminded McCain one tenet necessary for a happy life in the defensive backfield. “Watch ’em keep coming,” Howard said, the ’em meaning interceptions. One down, nine to go.

One week later, at Hard Rock Stadium, Seahawks quarterback Russell Wilson and burgeoning star wideout D.K. Metcalf spent a Sunday afternoon reminding Howard that even the best corners in pro football must possess far more than athleticism and intellect. They must trust their skills, their preparation and, ultimately, themselves.

They must rely on a short memory, which might sound counterintuitive, given everything they need to retain—technique; assignment; the strengths, weaknesses, preferences and tells of different wideouts; the same for their teammates; how the defense functions together—on a given play. Remembering what to remember matters to cornerbacks more than any other position on a football field, except quarterbacks. They want to remember what matters, what helps on the next play, in the next quarter. But they must forget what fans and analysts will remember most.

Pick 2: Week 4, third quarter, one-score game, Seahawks driving. The box score will show that on this afternoon in early October, Wilson will target Howard seven times and complete six of those passes for 119 yards. Howard will lament how Metcalf seemed as open as a 24-hour convenience score, which the cornerback will attribute to a schematic wrinkle from the Seahawks, who exploit the Dolphins’ secondary with a variety of post routes. By the time Seattle lines up six yards from the end zone on a third-and-goal, Howard believes he has dropped four picks in almost four games. That’s no way to get to 10. He’s mad about that, about Metcalf, about another game tilting toward defeat, the Hawks up, 17–9. “[Corners] need to trust everything that led to there,” he says. “You can’t dwell on the play before.”

Howard hears the play call from his linebacker. He likes the choice, senses an opportunity. He figures Seattle will attempt a quick snap, and that’s exactly what happens. Metcalf runs a bang route, the “bang” referring not to play design but to timing. Wilson is supposed to drop back quickly and deliver, without much consideration. That’s exactly what happens, too. Only Howard, unencumbered by disappointment over a difficult day on his island office, sees what’s happening, trusts himself and undercuts Metcalf to steal the ball. This happens so sneakily that the commentators don’t see the interception at first, not until Howard takes off running.

This pick turned the momentum of a close game. The Dolphins kicked two field goals, cutting the deficit to 17–15, but ultimately fell, 31–23. Howard had given his offense a chance, the mark of a cornerback who can change the tenor of a game with one play. He was most upset that he didn’t attempt to run the interception back, charging the length of the field into SportsCenter’s top 10 plays. On that goal list, next to DEFENSIVE TOUCHDOWNS, he had scribbled “2.” Still, that play marked a second straight game with a turnover. Interceptions. Bunches. That Corner Life. Two down, eight to go.

His response reinforced to Howard a valuable lesson, one he planned to carry into weeks when teams decided to throw away from him, limiting his opportunities; or weeks like that one, when he would be assigned to shadow one of the top receivers alive. Same mindset. Same short memory. “Make ’em pay when they throw the ball your way,” he says.

Combined, these tenets open a window into Howard’s approach to his craft. They long ago formed the baseline for his ascension from high school quarterback who rarely threw to Baylor cornerback with much to learn to All-Pro corner who signed a mega-deal in 2019 and successfully renegotiated it two years later. By then, Howard ranked among the NFL’s best corners, nearby or alongside Jalen Ramsey, Jaire Alexander, Tre’Davious White, Marshon Lattimore and Marlon Humphrey. He also knew one thing that could separate him: those 10 interceptions.

Pick 3: Week 5, San Francisco, jealousy, the good kind, wafting in the air. McCain nabs an interception and while they celebrate on the sideline, Howard says, “I’ve got to get me one.” The Dolphins are putting a beating on the injury-plagued 49ers despite another missed opportunity for Howard, whose teammates are making fun of him for the interception that hit him in the hands and landed on the turf. Then, boom. Quarterback Jimmy Garoppolo overthrows his intended target and the ball floats toward Howard like a gift. “That’s the crazy part,” he says. “Every pick I had gotten before in the NFL, I had worked for. But when that ball came, I’m like, oh, hell yeah. I got this. This EASY.”

The lesson: effortless interceptions count the same as acrobatic ones. Even in art, there’s luck. Seven more picks to go.

Five games into last season, the Dolphins were inching toward respectability, having won two of their previous three contests. Howard had forced turnovers in two of those victories. Where outsiders looked at 2–3 and saw another middling season, the star corner noticed something else with his team: progress. After all, Miami had four playoff appearances in the 21st century. “Nobody wants to be on a team for a so-called rebuild,” he says. “Some of [the players] bought in and believed. Some of the guys didn’t buy in; not here.”

Pick 4: Another game, another missed INT opportunity. But Howard likes his chances against quarterback Joe Flacco, in part because Howard played for Adam Gase, then Flacco’s play-caller with the Jets. He knows more about Gase’s tendencies than he does other coaches’, and when he sees Flacco drop back in the second quarter, he can sense what’s coming: a dump off to Jeff Smith. Flacco throws the ball behind his intended target, where Howard waits.

This interception—six to go!—resulted from his knowledge not of defensive football but of offensive tendencies. He came to understand those at Wheatley High in Houston, where he focused more on playing quarterback than defending signal callers. Howard’s coach there, Mario Lewis, can still recall Howard’s final high school game, where he rushed for 185 yards, passed for 245 more, scored four times on offense and returned two interceptions for touchdowns.

Lewis wasn’t surprised. He first spied Howard on the basketball court, entranced by the kid’s natural athleticism. He knew that Howard also ran track, and that football wasn’t his focus. But he also believed that Howard’s future was on the gridiron.

So Lewis began to build his case. He convinced Howard to play football, then swayed him to take football as seriously as he took basketball. He pointed out that, at 6-foot-1 and nearly 200 pounds, Howard would be an undersized hooper who might obtain a Division-III scholarship. But his instincts, his build and his work ethic made him a better fit in another sport. Eventually, the coach’s persuasion took. Howard landed a scholarship at Baylor. A football ride. Not a basketball one.

Howard often looks back on those days and laughs. He had no idea what he didn’t know back then—which was, well, pretty much everything.

In 2020, his turnover streak would be snapped after the Jets game. He would not record an interception in victories over the Rams and the Cardinals. But, against the Chargers in Week 9, he would lean on what he learned at Baylor.

En route to all the accolades, Howard picked up tips from other top defensive backs. One came from Richard Sherman, who reminded Howard that film study extended beyond understanding scheme and knowing quarterbacks. He also needed to study, really study, wide receivers. As the Dolphins prepared for rookie sensation Justin Herbert, Howard decamped to the film room.

Pick 5: Fourth quarter. Something clicks. He sees wideout Mike Williams lined up right and senses what’s about to happen, because he had studied this exact scenario on film. He guesses the right play, his speculation so spot on that he expects the linebacker in front of him to pick the ball off. But as the play unfolds, he notices the linebacker is out of position. No worries. He sprints in front of the ‘backer, then in front of Williams, and when the receiver breaks for the ball, he’s already there.

At that point, Howard stood halfway to the interception goal he spied in the bathroom mirror every morning. He attributed that to the extra time he had spent hunched over his iPad—and the season at Baylor where he red-shirted, in order to learn a craft, the art of cornerback play, he did not yet know existed.

In Waco, Howard learned how to study. He started by watching the Big 12’s top players at his position, future first-round picks like Jason Verrett (TCU) and Justin Gilbert (Oklahoma State). He tried to mimic their technique in practice, while defending a bevy of future NFL receivers. He listened to his coaches. He continued to dive deeper, studying the elite professional cover artists like Darrelle Revis, Champ Bailey, Patrick Peterson and Sherman.

The combination of focuses birthed a higher level of confidence, because Howard still possessed all his natural ability; only at Baylor, he learned how to utilize his genetic gifts. Along the way, he discovered that he’s a visual learner—which was important, because he knew that he could see something and implement it, instantly. He absorbed how to defend various route combinations, how to approach taller receivers compared to shorter ones, how to use his size—big for a corner—to his advantage.

In his final season, 2015, he made first-team All–Big 12. He started to remind his high school coach, Lewis, of Lewis’s college teammate, Al Harris. The same Al Harris who played 14 NFL seasons for four franchises, in large part because he understood the art.

The pick Howard snagged against the Chargers saved another Dolphins victory. Miami was suddenly 6–3, in playoff contention, on a five-game win streak. Howard’s career interception per game average hovered around 0.40, the highest of any NFL player since the start of the 2017 season.

The total number of interceptions would have been higher, if not for a series of injuries to his left knee that landed him on injured reserve in October of ’19. Doctors fixed what Howard describes as a “hole in my knee” with multiple surgeries. The recovery took nine months, three of which he spent on crutches. Looking back, though, he believed the decision to be careful only added to his superpowers, making him indestructible, at least in his own mind, where he decided he would return from that rehab and nab 10 interceptions.

“I started to feel like, if I didn’t get one, I ain’t do nothing good,” Howard says.

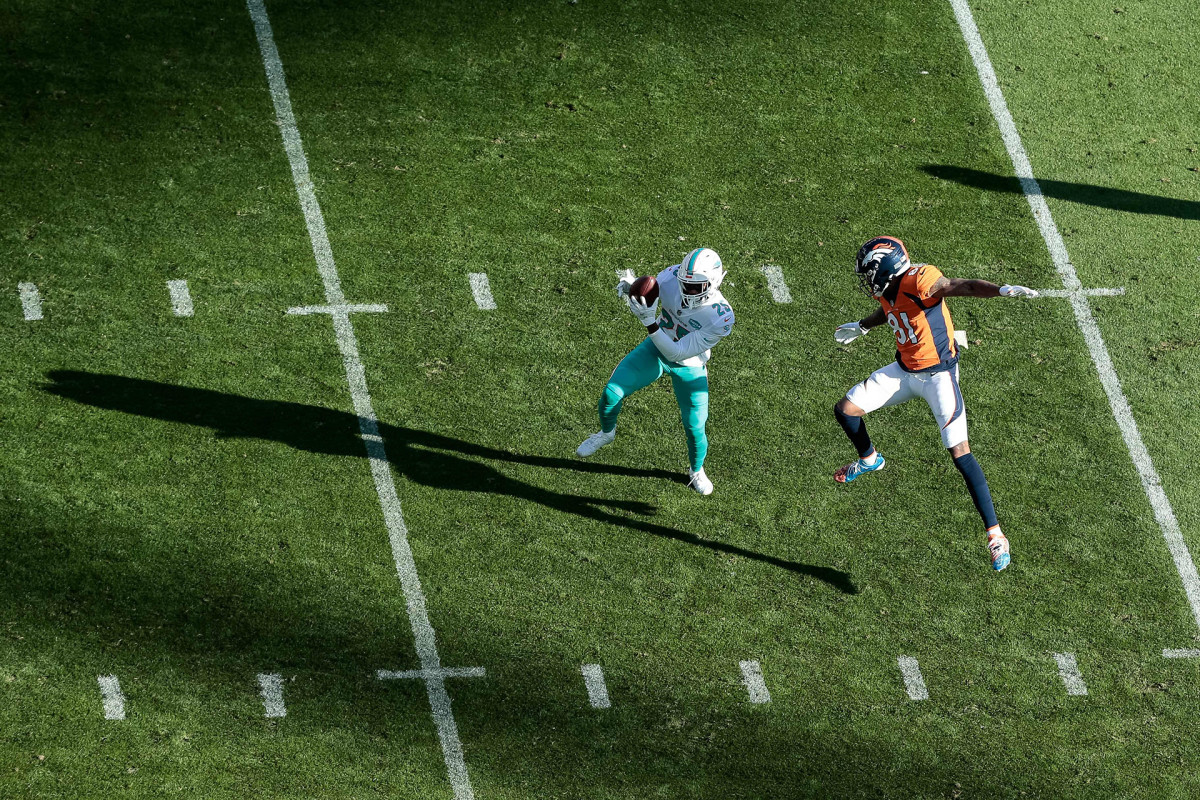

Pick 6: (No, not that kind.) It’s Week 10. Howard and the Dolphins are in Denver, where he’s salivating, because he’s facing an inexperienced and sometimes inaccurate passer in Drew Lock. Against that type of quarterback, Howard focuses on his positioning—of his body, of his feet. That’s part of trusting himself, another tenet. Right position, right feet, then look back for the ball. For most of this game, the Dolphins are in man. When Coach Brian Flores switches to zone, Lock is momentarily confused. He forces a pass toward the middle of the field, where Howard lurks, in perfect position. “He threw the ball right to me,” Howard says. “But I set him up on that one.”

That particular interception—only four to go now—overshadowed the consistency that Howard maintained that day. Flores made sure to point that out to reporters who are mesmerized by all the picks. Those plays, as important and flashy as they are, represent a fraction of the total plays. Part of what separates a craftsman like Howard are the 99% of snaps that the casual observer doesn’t notice.

Howard, Flores said, possessed supreme—and supremely consistent—cover skills, the kind that coaches notice but the general fan never sees in detail. Howard had also improved in blocking and tackling, showing he cared about becoming a complete corner, rather than just a ball-hawking one. Howard saw these gains as necessary, knowing that artists can improve by giving themselves more brushes, or different paint.

The loss to Denver had pushed Miami, at 6–4, to the playoff fringe. Howard’s interception goal had become even more important, because it tied directly to his team’s playoff chances, as the Dolphins traveled to New Jersey to play the Jets.

Pick 7: In a second divisional match-up with Gang Green, Sam Darnold has recovered from early-season injuries and replaced Flacco under center. Howard sees this as a positive development—for him, anyway—because while he terms Darnold a “good” quarterback in the same neighborhood as teammate Ryan Fitzpatrick, he also says Darnold, “throws the ball, and he don’t care.”

The Dolphins defense backs up this assertion on a Sunday afternoon in late November. They dominate the Jets, holding Darnold and his teammates to three points. Howard plays a complete game, despite a dropped interception that prompts Jets safety Jamal Adams to heckle him from the sidelines. And there, late in the fourth quarter, Darnold throws a careless pass toward his slot receiver, connecting with Howard instead.

Seven down, three to go, and yet even the latest turnover didn’t fully capture Howard’s value. Darnold threw at him 10 times, completing only three passes for a measly 37 yards and a passer rating of 2.9.

There’s a lesson, too, in that turnover and his next one. That interceptions matter, but not as much as wins. As the season had progressed, Howard continued to play at higher and higher levels. He concentrated less on the goal scribbled onto that sheet of paper in his bathroom mirror—and, lo and behold, his hands continued to find footballs intended for receivers, and those footballs continued to crowd the space allotted for them in his “man cave.” To Howard, this reinforced another tenet: patience. Do the right things, over and over; forget mistakes; study; and let those small steps guide him to larger aims.

Pick 8: Week 11, at home against Cincinnati, facing another inexperienced signal caller in Brandon Allen, starting in place of the injured Joe Burrow. “Easy,” Howard says of his interception. Patience pays off. Miami improves to 8–4, their season ranking among the most startling developments of 2020 in the NFL.

Just how much any of the tenets would pay remained an open question, one that bugged Howard throughout last season and lingered afterward, in a contract dispute that lasted all the way until this fall. Speculation swirled that Howard would be dealt after the Dolphins inked fellow corner Byron Jones to another big-money extension.

Howard desired compensation that matched his season, all the interceptions, the art he was in the process of perfecting at a level as high as any corner in the NFL. But teams don’t generally want to blow up contracts that were signed only a year earlier, especially contracts that contain that many zeroes.

All that left Howard in an uncomfortable position. He knew that Miami’s surprise postseason bid had been driven by its defense, particularly the secondary. He liked his teammates and understood their value to each other, how defensive coordinator Josh Boy could amp up his aggression, calling blitzes, knowing the Dolphins could cover targets with fewer defenders than most NFL teams needed. But Jones now made more than him based on yearly averages ($16.5 million to $15.1 million)—as did Ramsey ($20 million), Humphrey ($19.5M), White ($17.25M) and Darius Slay ($16.7M). Howard had to ask himself tough questions. Was that right? And, did it matter? Hadn’t he signed the deal now in place?

In Week 14, the Dolphins would host the Chiefs and their high-powered offense. Coach Andy Reid would tell reporters that Howard was “playing as well as any corner in the league right now.” Even if that was an exercise in flattery, it was accurate. And part of how Howard maintained his elite production level resulted from shelving the concerns over his contract. He couldn’t beat Patrick Mahomes without complete focus, leading to another tenet familiar to the best corners in pro football: the ability to compartmentalize, so that when a big moment nears, it can be seized.

Pick 9: The Chiefs mainly stay away from Howard, which is happening with increasing frequency as the season rolls along. The film doesn’t lie. Nor does the interception tally.

Early into the fourth quarter, the Dolphins are down and Mahomes is dealing. Miami needs some sort of momentum-shifter, a Howard specialty. He’s shadowing Tyreek Hill on a first down, the task ranking among the least enviable in football due to Hill’s cheetah-like speed. But as Howard gives chase on a deep fade route, Mahomes makes a rare mistake, as his pass falls shorter than intended. Howard believes too few corners look back for the ball, always, but that’s one of his tricks. This time, when he turns his head, he’s perfectly positioned—and, now, only one interception from his ridiculous goal before the season started. The Dolphins score twice, embarking on a furious rally, but ultimately lose, 33–27.

This particular turnover made SportsCenter’s top 10 list. Howard would later describe it as “special,” because of who he was defending and who lobbed that throw deep down field. Mahomes had found him afterward to remind Howard of their shared history, which, of course, Howard himself had not forgotten. “You’re the only cornerback that picked me off in college and in the NFL,” Mahomes said, making Howard giddy.

By the end of Week 14, Howard had nabbed more interceptions in a season than any NFL player since the 2012 season—and he still had three games left. The Dolphins ranked second in the league in points allowed per game, in significant part due to Howard and his craft. His speed, ability to change direction and positioning made him the rare corner who could shut down half a football field and follow speedy receivers like Hill into the slot. Only Ramsey can compare to that type of versatility.

Still, Miami entered its final week of the regular season needing to beat Buffalo to make the postseason. Howard had gone two weeks—the horror!—without a turnover, but his team had beaten the Patriots and Raiders anyway. Could he match his goal? Of that, he was certain.

Pick 10: He does, intercepting Matt Barkley in the third quarter. He reaches his goal. Ten picks, the most in the NFL since 2007. Tied for a franchise record. But even this is anticlimactic, as the Dolphins lose and their season is halted.

Even then, Howard made the short list of nominees for defensive player of the year (he finished third). He had played the entire season after his knee had been repaired without issue. He still wanted a new contract.

This summer, he threatened to hold out (and eventually staged a “hold in” during training camp), going public with his contract and trade demands on his Instagram account. He changed agents. Eventually, Howard and the Dolphins reached a compromise, with the team shifting money into the 2021 season, guaranteeing his base salary for this year and turning ’22 bonuses into base salary, with the promise for more negotiations ahead.

Along with his marketing rep, Polo Kerber, Howard charted a course for how to capitalize on his special season. Kerber found the cornerback to be soft-spoken, devoid of trash talk, the antithesis to Ramsay. But Howard, because of his art, was also marketable. He needed to sustain momentum. If he did, Kerber says, “he can be a face-of-the-NFL-type player.”

Howard’s statistics simplified their argument. According to Pro Football Focus, his 62.5 percent passer rating allowed over the last three seasons ranked as the third-lowest such figure since 2018. He also ranked as the second-highest player at his position in terms of percentage of targets broken up or intercepted (23.4%). His PFF grade of 89.6 marked a career high; only Ramsay topped it and both of their marks bested Stephon Gilmore’s production for the Patriots in 2019, when he won Defensive Player of the Year.

As for Howard, he simply went back to work. After all, for an artist, compensation matters. But never, not even in pro football, does it matter as much as craft.

When Howard returned to action in the preseason, he faced Matt Ryan and the Falcons. What happened? Another interception, of course, along with a new goal list. “I want 20 this year,” he says.

More NFL Coverage:

• Dak Prescott’s Heal Turn

• Why the NFL’s Trendiest Offense Is Harder to Copy Thank You Think

• Orlando Brown Jr. Followed His Father and Forged a New Path

• Nathaniel Hackett: Neurobiologist. Hip-Hop Dancer. Future Head Coach.