Why Pass Rushers Will Rule the 2022 NFL Draft

You can contact Dr. Rush by calling 1-833-222-SACK, a number he registered personally with the phone company in Atlanta.

And on the first day of specialized training with pass-rush instructor Chuck Smith (the name on Dr. Rush’s driver’s license), he’ll ask you to toe the end zone, walk you out to the 5-yard line and turn you back in the direction you came. Five yards, or the typical distance from a pass rusher’s starting point to the quarterback, is all that matters. Then, he’ll walk you out to the 10-yard line and inform you that if you ran this far on a play, you likely missed the quarterback altogether. He’ll walk you out to the 40-yard line, the distance most of his collegiate prospects spend draft season worrying about, and ask: Who among you has ever run this far to sack a quarterback?

Crickets. Point taken.

While this all might feel a little tawdry, like a modernized Tom Emanski VHS skills and drills pitch, it’s anything but. Especially now. Smith, who played nine NFL seasons and spent time postcareer as a coach with the Jets, Ravens and University of Tennessee, is sought out by players all over the country who find themselves punching S-A-C-K into their phone’s keypad. He works regularly with Steelers All-Pro Cam Heyward and Raiders edge rusher Maxx Crosby, now one of the richest players in professional football. Von Miller considers him his personal Phil Jackson, and Aaron Donald says Smith taught him one of his most potent moves, the club chop. “If quarterback is the most important position, [the player] stopping him, a pass rusher, must be the second most,” Dr. Rush says.

When specialized predraft pass-rush training, which mimics the cottage quarterbacking industry popularized by Tom House, Steve Clarkson, George Whitfield and Jordan Palmer, went mainstream, the choice for an industry superstar—its first doctoral graduate—was obvious. Smith’s phone line is constantly tied up because pass rushing is having a moment. Ten of the 11 highest-paid defensive players in the NFL are categorized as some variety of pass rusher. The great ones make more than $20 million per year and, in 2022, even the mediocre ones saw their prices soar like some animal-themed cryptocurrency.

That’s because recent developments in the NFL have changed the perception of the position and upped the urgency to secure a pass rush. In an effort to slow down a generation of superhero quarterbacks—think Patrick Mahomes, Josh Allen, Justin Herbert—defenses have largely abandoned blitzing in favor of coverage, hoping to stymie offenses by flooding the secondary with cornerbacks, safeties and linebackers. That means edge rushers need to win more consistently, carrying the burden of pressuring quarterbacks all on their own.

The Rams won a Super Bowl because of their pass rush. The Bengals made a Super Bowl thanks in large part to the signing of free-agent edge rusher Trey Hendrickson to pair with Sam Hubbard; in their second-half shutdown of Mahomes’s Chiefs in the AFC title game, the Bengals often rushed only three and dropped eight players into coverage.

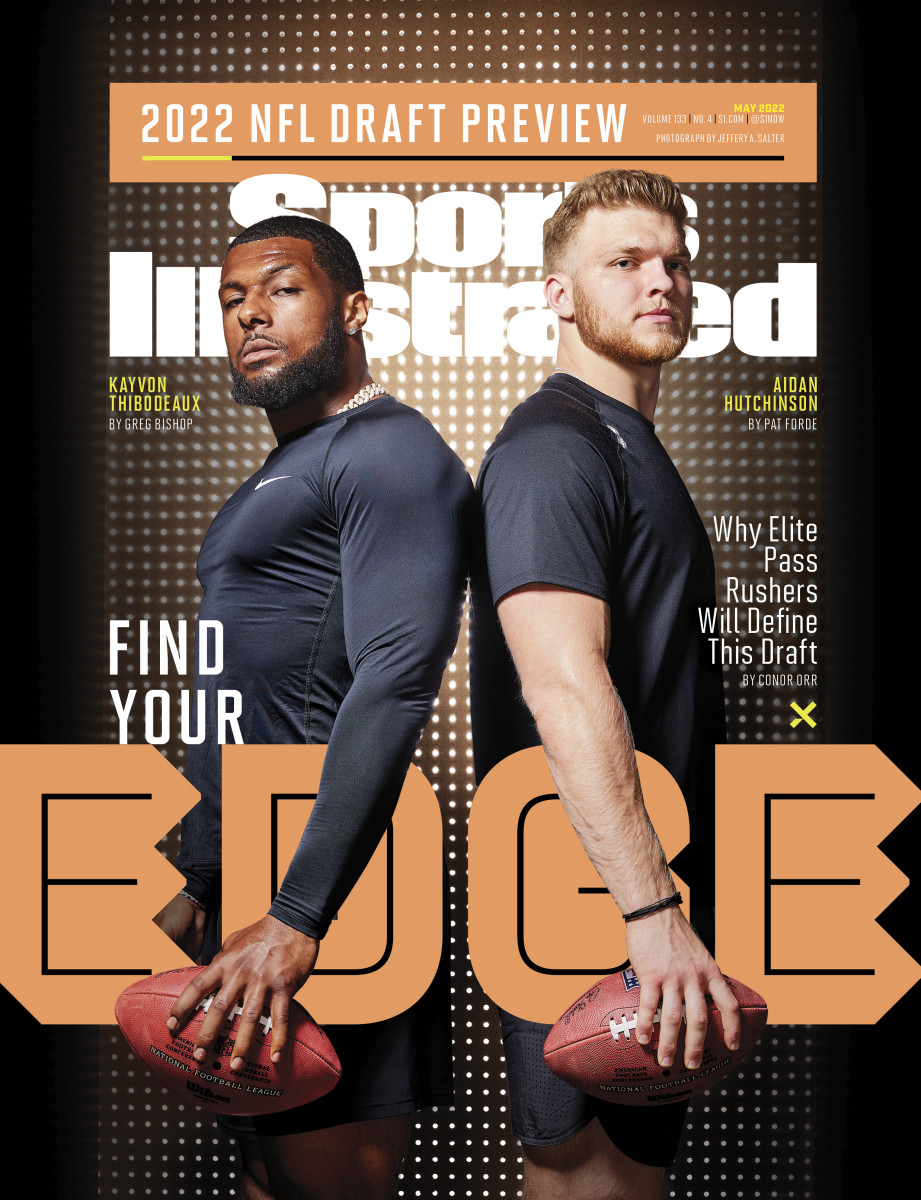

The 2022 draft class is being welcomed by executives desperate to find pass-rushing talent. Aidan Hutchinson and Kayvon Thibodeaux could be the top-two picks. Travon Walker, Jermaine Johnson and George Karlaftis could all go in the top 15. Trent Baalke, the top personnel executive in Jacksonville, said he viewed this pass-rush class as brimming with talent into the third round. Smith thinks it’s even deeper.

When asked about Hutchinson and Thibodeaux in particular, the two rushers likely to come off the board first, one personnel executive used one of the most generous descriptors in the scouting football-guy lexicon: “Real Dudes.”

How did we arrive here? At a time when a pass-rushing academy has its own hotline? When the waitlist for pass-rush help seems longer than the one for an elite Brooklyn Heights preschool? When, at the scouting combine in Indianapolis, general managers expressed concern about overpaying for premium veteran talent but soon did so, anyway? When a draft that lacks a surefire quarterback might still be one of the most consequential collegiate crops to enter the NFL in almost a decade?

If there is a pass-rush academy, there must also exist pass-rush economics. Consider this a crash course. If you learn only one thing: Nothing is more valuable than the pass rushers headlining this draft class.

Also Read: Aidan Hutchinson’s Rise to the Top of the Draft

At some point midway through the 2020 season, teams collectively decided that the attrition rate on blitzes against great quarterbacks was too much to handle. Outnumbered defensive backfields were being torched by a gilded age of passers raised in chaos and better equipped to handle free rushers and exotic pressures. Mahomes and Aaron Rodgers, running entirely different systems each predicated on knifing open mismatches and isolating players against favorable coverage, were toying with opponents so flagrantly that it was only a matter of time before someone decided to abandon their core principles altogether.

That meant a bevy of teams deploying split-safety defenses and abandoning the blitz altogether, increasing the number of defenders dropping into coverage. The trend began creeping into the mainstream when half the Chiefs’ opponents increased their usage of that approach—pulling back on their blitz rate by between 10% and 50% when facing Kansas City. It worked in the way a Band-Aid might cover up blunt trauma as the Chiefs still won 14 regular-season games, finished in the top three in all major statistical passing categories and made the Super Bowl.

In 2021, blitz atheism was more widely adopted. The Chiefs’ offense sputtered for half the season—and fell in the AFC title game to a Bengals defense sometimes featuring that three-man rush—as Mahomes became one of the least-blitzed quarterbacks in football last year. He saw an extra pass rusher roughly seven times per game; Rodgers saw only eight blitzes per game. According to Next Gen Stats, the Bills didn’t blitz Mahomes a single time in the first half of their 2021 regular-season game, which was one of only two times in the statistical service’s history that zero blitzes were called in an entire half of football. The other? The Bills’ previous regular-season game against the Chiefs, a little less than a year earlier.

It went unnoticed to most casual observers, but Mahomes was now having to strain ever so slightly to squeeze the 10-yard pass to Tyreek Hill. His sidearm passes—shoulders slumped, hooking the ball around a defender in his face, became more of a necessity and less of a showpiece.

Leaguewide, only four teams—Tampa Bay, Miami, Carolina and Arizona—blitzed on more than a third of opponents’ dropbacks; the previous season, 11 teams did so. The Buccaneers led the NFL with a 40% blitz rate. Last season the league-wide blitz rate was 25.4%, the lowest since TruMedia started tracking the stat in 2013.

Of the eight teams that blitzed least frequently last season, only two—Houston and Indianapolis—missed the playoffs. The Colts missed the postseason by one game, and their defensive coordinator, Matt Eberflus, was hired to become the coach of the Bears. Lovie Smith, the Texans’ defensive coordinator, was promoted to coach in Houston.

“This goes way back,” Eberflus says. “Rush four, drop seven. Don’t open up the lanes for the passing game. That’s been our philosophy, our system, going back to the Buccaneers in the 1990s [under Tony Dungy] and the Bears of the 2010s [under Smith]. I just basically kept that philosophy. We’re going to rely on speed, quickness and hitting ability to take away big plays.”

In today’s NFL, where swaths of rule changes and years of more talented athletes migrating to offense make defending top-tier passing games almost purposely impossible, the shift allowed defensive coordinators to basically choose a more favorable demise. Instead of being gutted by embarrassing 70-yard highlight touchdowns, they could slow the process down and hope the opposing offense would trip itself up and short-circuit a drive.

“Teams don’t want to give up the big play,” Commanders coach Ron Rivera says. “But it’s also about who you play. If you’re playing Green Bay, you’re going to be a little bit smarter about those things. I still think blitzing is a valuable weapon.”

Rivera’s starting D-line is made up of first-round picks.

Teams have always needed pass rushers. It is not a trend-specific position, like fullback or a thick-bodied box safety, that cyclically becomes popular every few years. And yet, there was something about athletic defenders who could bend around the edge of a left tackle and whack the quarterback that seemed so much more essential now. Among GMs and coaches at the combine, there was a sense of helplessness when it came to finding an immediate answer at pass rusher.

“You just need guys to win one-on-one,” says one GM in need of pass-rush help. “There aren’t that many of those guys around.”

Also Read: Kayvon Thibodeaux Hears His Critics, and He Has A Plan

Just a few days before Super Bowl LVI, Bengals director of player personnel Duke Tobin was trying to protect himself from the Southern California sun, hiding beneath a pair of sunglasses and a flat-brimmed baseball cap as he stood in the withering shade. He looked out at a few makeshift podiums in the stands bordering the UCLA track and field facility, where a core group of Bengals were doing interviews with reporters from all around the world. This was a Super Bowl team he helped build, one that he felt confident in at the beginning of the season. Internally, the Bengals wondered why no one else saw their roster the way they did.

One major reason for their turnaround was Hendrickson, signed from New Orleans the previous offseason, who logged a career-high 14 sacks in his first year with the Bengals. The 2021 free-agent class was stocked with talented edge rushers, but because of the pandemic the salary cap was projected to shrink and most clubs shied away from spending money.

For Cincinnati, that meant a player such as Hendrickson, who in 2022 would have commanded more than $20 million per season, was landing closer to the $15 million range. Tobin and his staff usually compile a list of targeted free agents before handing them off to their coaches to cross-check.

“We put a value on a player: Here’s who he’s like; here’s where we feel his dollar value should be,” Tobin says.

Because they didn’t deviate from their non-pandemic process, the Bengals were prepared to capitalize on what would become a massive market inefficiency. Hendrickson received offers from a half dozen clubs, prayed on his decision with a close network of friends and family, and signed a contract that paid him about as much as a solid No. 2 wide receiver.

Tobin, Bill Belichick in New England (Matt Judon, $13.625 million per season), Jon Robinson in Tennessee (Bud Dupree, $16.5 million per season) and Joe Douglas of the Jets (Carl Lawson, $15 million per season) all saw what others could not—or perhaps what other owners would not allow their general managers to see with their checkbooks buried in some survival shelter. This was a deal of a lifetime.

“We thought certain markets would get hit hard with the cap going down, but we didn’t think the premium markets would get crushed,” says one general manager describing the great edge-rusher heist of 2021.

There were the Patriots amid their post–Tom Brady revival, collapsing pockets with three rushers, slingshotting Judon off the edge somehow unblocked. There was Hendrickson, wearing down the Chiefs snap by snap in the conference title game, clobbering Mahomes and holding K.C. to three second-half points in the upset.

Just before free agency, one general manager predicted that edge-rusher salaries “are going to skyrocket.” He was right. Last offseason’s sale turned out to be one-time only.

In early March there was Randy Gregory, a player with career highs of six sacks and 29 pressures who has never played 500 snaps in a season over his seven-year career, at the center of a bidding war, landing $14 million a year from Denver. There were the Dolphins paying $16.35 million per year for 28-year-old Emmanuel Ogbah, following a pair of nine-sack seasons. Crosby signed a new deal worth $23.5 million per season, which is still $4.5 million below T.J. Watt’s market-resetting $28 million per year deal signed last summer. A couple of aging vets, 33-year-old Von Miller ($20 million in Buffalo) and 32-year-old Chandler Jones ($17 million in Las Vegas), landed larger deals than any edge rushers in the 2021 free-agent class.

Because of the depth of this edge-rushing draft class, those prices might have been slightly deflated. Many teams are choosing to try their hand at the rookies—and the more reasonable rookie wage scale—instead. If, for instance, the Jaguars select Hutchinson or Thibodeaux with the first pick, the player would receive a contract of $41 million over four years ($10.3 million per year) with a fifth-year option for the team. If, say, the Eagles (or a team acquiring one of the three first-round picks owned by Philadelphia)—who in March inked veteran pass rusher Haason Reddick, now on his third team, to a three-year deal with $15 million annually—were to select a pass rusher 16th, that player is locked into a deal paying him $4.1 million per season over four years.

This draft not only offers some intriguing pass-rush talent, arriving at a time when defenses need it most, it also offers it at a severely discounted price.

George Karlaftis arrived for his Saturday workout just after noon in a dark T-shirt and white shorts. Inside a massive Carrollton, Texas, facility owned by longtime NFL cornerback and current Fox broadcaster Aqib Talib, the first-round prospect out of Purdue arched his body into a nimble sprinter’s stance and began to practice the speed at which he would pop off the line and run toward the quarterback.

Karlaftis was working with the Trench Warfare group. Brandon Tucker, another private pass-rushing specialist, calls his students the Quarterback Hunters. On some social media channels, he said he is known as the D-Line Guru (“I’ve been called worse, I promise you that,” he says).

“Guys get paid off their pressures and their sacks,” Tucker says. “It’s a specific skill set that may or may not be covered by their position coach or in practice. Just like anything else you specialize in, you go find a skills coach.”

As for the desired results, he adds: “You’ve got to be able to hit home on a one-on-one situation seven out of 10 times.”

Karlaftis was weaving his way through staggered cones, softly backpedaling at a 45-degree angle and then bursting forward to the next front-facing marker. In that moment, watching his 6' 4", 266-pound frame move forward, subtly picking up speed with each step, one gets a sense of what it might be like to get hit by a Martz bus.

“I call guys like George one-percenters,” Tucker says. “He has found in his style of play what really works for him. His speed to power, his bull rush is absolutely phenomenal. He’s not an imposing-looking defensive lineman, but when you put on the tape, you see a guy who is giving max effort on every play, someone who is absolutely going nuts on the field.”

The class of 2022 has all different kinds of body types and skill sets. Smith, the pass-rush doctor, says that, as at the QB position, the league has become more welcoming to nontraditional pass rushers. People care less about what someone looks like whipping around the edge and tossing a quarterback to the ground and more that it happens.

Of Thibodeaux, he says: “He can change games because of his explosiveness, his ability to shift weight and bend. . . . When you’ve got that kind of movement, you’re going to be hard to stop. In that five-yard area, he can bend, spin, long-arm and change direction. And he understands he’s still a work in progress.”

At some of Smith’s camps, there are these beautiful moments when a bunch of prospects line up in front of large, red plastic dummies, their padded arms stretched out wide, each resembling an offensive tackle getting his bearings. All at once, a dozen kids will pop out of their stance, approach the dummy and groove their upper body underneath the outstretched arm, finishing with their inside hand high in the air to fend off any comeback attempt. He took this video of Thibodeaux attacking a dummy with his inside hand before ripping the arm underneath it, dipping just beneath its head. He never lost speed. It was completely fluid.

Both Smith and Tucker have heard from professional clients who want to reboot their careers and switch positions. Smith thinks about a time when he was younger, when everyone wanted to just play quarterback and running back. On a larger scale, he knows there is something happening here. Defensive philosophy has shifted; pass rushers are having more than just a moment.

“Now, everyone is saying, ‘You can be a pass rusher,’ ” Smith says. “That’s where the money is at.”

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Aidan Hutchinson’s Rise to Potential Top Pick

• Kayvon Thibodeaux Hears His Critics and Has a Plan

• Behind the Spectacle of Kaepernick’s Comeback Tour