2022 NFL Draft: Kayvon Thibodeaux Has a Plan

Kayvon Thibodeaux strolls past palm trees, oceanfront condominiums and tennis courts. He’s shoeless, sore, exhausted and surrounded by a cocoon of confidants, nearly a dozen total, from trainers to managers to a publicist, childhood friend and camera guy. They’re all headed to the beach, ostensibly for yet another pre-draft workout. But there’s another, ulterior reason for this not-at-all impromptu gathering: There’s a story they’re here to tell.

Couples walk dogs across the sand in Santa Monica, the famous pier and Ferris wheel looming in the background. Old dudes rally on the hard courts. A piney smell, probably weed, drifts through the air. Garbage trucks empty bins near lifeguard stands. Thibodeaux is silent, a tranquil contrast to the mid-morning St. Patrick’s Day activity. The pass rusher from Oregon acknowledges a fan shouting “Go Ducks!” as his workout begins. He lunges, jumps and sprints, training for the upcoming NFL draft underneath a cloudless sky, sand flying from feet. “It feels like it has been two years,” he tells a friend. “But it has only been eight weeks.”

Thibodeaux means the draft prep, the ever-intensifying microscope hovering overhead and the criticism lobbed his way. Once the top-ranked player in the 2019 class of college football recruits, most analysts long presumed he would go first in the ’22 draft. But as draft season unfolds, nebulous criticisms threaten to nudge him down draft boards. Doesn’t work hard enough, they’ll say; or, too many outside interests. But the eight weeks of toiling weren’t about proving “them” wrong. They were about proving himself right.

Everyone around him wants something, either from Thibodeaux or for him. What he wants is to speak for himself, through a day in Los Angeles stuffed with words, workouts and meetings. Joggers lumber past. A seagull perches atop a stoplight. Skateboarders zip by. Thibodeaux grabs a towel and wipes away the sand.

Away from the beach, Thibodeaux climbs into a black Mercedes sedan. He’s steering through L.A., toward a restaurant with the perfect name: My 2 Cents. Why were those eight weeks so draining? The constant grind, he says, so many obligations, all the meetings and interviews and film shoots. “All the stuff that has nothing to do with football.” Thibodeaux sees a disconnect between how the public might view him this spring and how he believes NFL teams interpret his pro potential. He says the media wants to keep “the story” going, but their version, not his.

“The outside world has no real idea,” he says. The mistake, as he sees it, is comparing him with established norms. He’s a defensive lineman, so he’s supposed to be less intelligent, per the stereotype. He grew up in South Central, so he’s not supposed to believe he will be a billionaire—and soon. Because he’s a football player, why should he do everything else, from chess to branding to books to partnering, at only 21, with Core Prep Academy to open a middle school focused on development, empowerment and financial literacy?

“Might as well give them something to talk about,” he says, leaning into a common refrain for divisive athletes. That relevance matters above all.

There’s a point to all this. And that point is to answer a question that’s central to Thibodeaux’s future: How does a superstar athlete wrest back control of his own story?

Something to talk about doubles as a life summary. Before Thibodeaux dreamt big, he simply was big, even by the hefty standard of football linemen. At 6' 3" in sixth grade, he was routinely mistaken for an adult, needed to bring his birth certificate to youth football games and couldn’t fit under school desks for earthquake drills. Every time he entered a room, he could feel eyeballs lingering on his frame, wondering what to make of him. At first, the stares made him anxious. But eventually he changed his mindset, deciding to use his size as an advantage, adopting a commanding presence and growing comfortable with himself.

His lofty gridiron aims began with Super Bowl XLVII, held on the night the power went out in the Superdome in 2013. A sideline camera captured linebacker Ray Lewis rallying the Ravens. Even though Thibodeaux was 12, he recognized Lewis “speaking words and life into his teammates,” as the speech helped vault Baltimore over San Francisco. “I felt that through the screen,” he says. That’s who I want to be, he thought.

Thibodeaux arrived at a resolution: He alone would define himself. Like when he transferred high schools twice in Southern California, eventually enrolling at tony Oaks Christian, where classes once included the offspring of famous athletes like Wayne Gretzky and Joe Montana. Others—always, the undefined “they”—could posit that he switched for football. He really went for academics, at the urging of his mother, Shawnta Loice. He maintained a 3.8 GPA and aced AP classes.

Thibodeaux navigated his new life through careful, deliberate action. He wanted to build on his parents’ strength—especially their adaptability, or “being good on the fly.” MacGyver is what he called his father, Angelo Thibodeaux, the dad who could fix anything from air conditioners to car engines. But rather than fixing along the way, Kayvon wanted to navigate his life through intention, the map of his future all laid out. “The only person I know that didn’t struggle without a plan was Columbus,” he says, laughing. “I don’t think there’s any more uncharted land. [Life] is knowing where to go and having a purpose.” Hence why he’s bothered by slow drivers inching along in the fast lane. Don’t they have somewhere to be?

Thibodeaux hated the transition from South Central to Westlake Village, a drive of only 43 miles that felt like a trip into another universe. But he had that plan to execute. He wanted to think strategically, so he picked up chess and went to Venice Beach to take on older experts. He wanted to excel at football, so he left home every morning at 3:45 to drive to the gym, adding thousands of miles to the odometer of his black Mustang. He sought out mentors like gym owner Travelle Gaines, Oaks Christian football coach Charlie Collins and retired NFL linebacker Willie McGinest.

In interviews, Thibodeaux trotted out motivational quotes, phrases like “Be somebody to somebody” and “Never change. Just grow.” He described giving back to the community, empowering people who, like his parents, were never given the resources they needed. He considered businesses, future wealth and potential partnerships while in his teens. And he spent hours with Collins, asking for the secrets of two NFL stars whom he coached (wideouts Chad Johnson and Steve Smith Sr.), debating the racial history of America, exploring ancestral roots and swapping book recommendations (topics: leadership, elite performance).

Thibodeaux understood the stakes. If he executed the plan, he could enact dramatic change—for his family, his neighborhood, himself. He viewed high school and college as “pit stops” on the way to something greater, with football the “bus” driving everything else. He would never become stagnant, never lapse into a comfortable approach.

Words would change his paradigm, he believed, whether through books, education or his telling of his story. He didn’t have to be anything other than himself. He moved easily between disparate worlds, with charisma and social grace. By the summer after his freshman year of high school, one recruiting service ranked him the nation’s top recruit in his class. All soon listed him in their top five. Utah offered his first scholarship. Then Alabama and Oregon and dozens of others did the same.

Thibodeaux trained so often that Collins jokes he wanted to “become a male supermodel.” All the while, he worked out three times a day, made a positive impact on his teammates, won a million football games, excelled in class and even chose Oregon over Alabama for its combination of football and academics. “Consummate team player,” Collins says. One who didn’t drink, vape or land in any trouble. One who, at that point, still controlled his story.

In draft profiles, experts rate Thibodeaux’s strengths the same as ever: size, length, explosiveness, balance, twitch. Only now, after his college career, new “weaknesses” have changed the conversation: raw, hand technique, ankle flexibility, too easily baited. “Typical bulls---,” says a prominent AFC talent evaluator in defense of Thibodeaux, his candor exchanged for anonymity. “I wouldn’t draft him,” says an NFC general manager who most definitely would, depending on when.

How Thibodeaux “fell” from the presumed No. 1 pick to somewhere lower starts there, with perceived flaws grounded in film study. What’s odd is that none of the evaluators called his college coach, Mario Cristobal, according to another direct source—Cristobal himself.

When describing his former star’s strengths, the coach uses one word at a time, pausing briefly between each for dramatic effect: “complete . . . athletic . . . instinctive . . . powerful.”

He sighs into the phone. “I don’t think people are giving him enough credit.”

After arriving in Eugene in 2019, Thibodeaux asked his coaches what he needed to improve on, and when they told him to gain weight and retain his explosiveness, he started right away. Quarterback Justin Herbert became his lifting partner; that fall, a stronger, bigger Thibodeaux netted nine sacks and won Pac-12 Defensive Freshman of the Year.

Thibodeaux didn’t limit his focus to on-field destruction. He sought out Phil Knight as a mentor and met with the Nike founder on Tuesdays for brainstorming sessions over coffee, a shoe dog and a sack one. Thibodeaux says Knight told him the NFT market would explode long before it did. Thibodeaux started referring to Knight as Uncle Phil and both, along with ace designer Tinker Hatfield, would partner on an NFT art collection last fall.

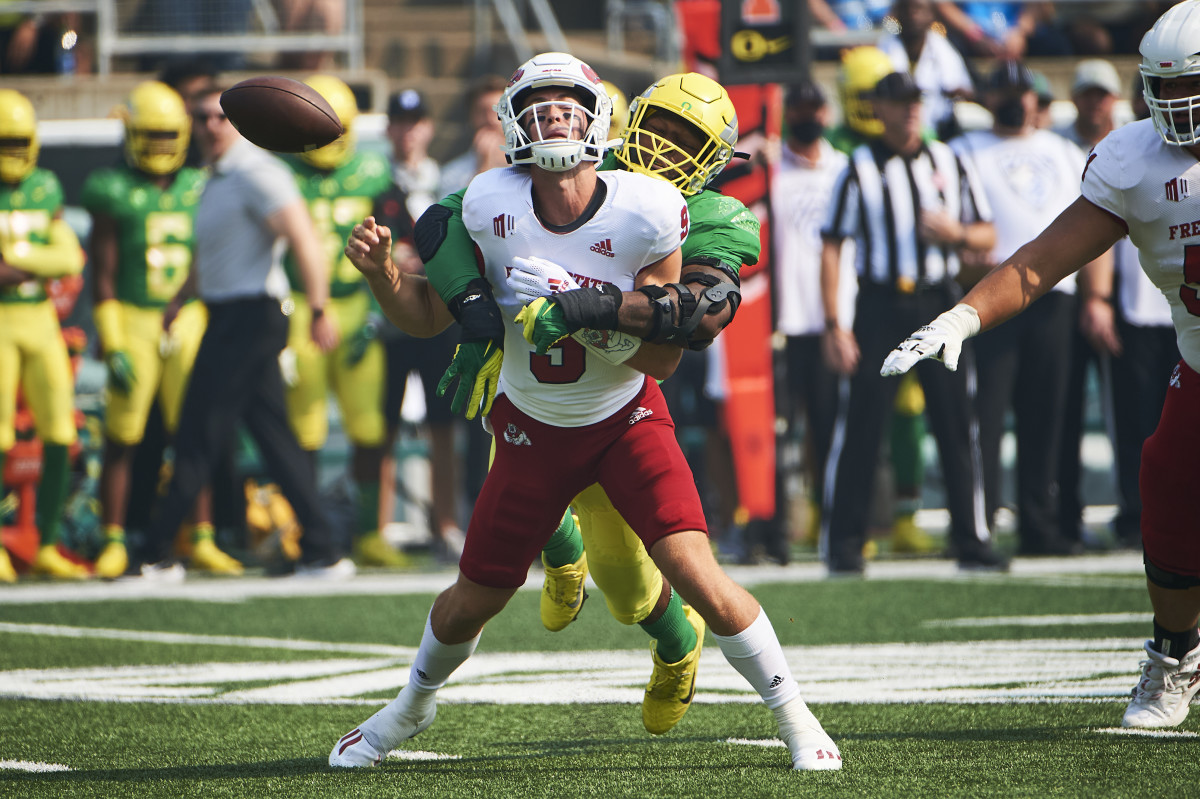

Over three seasons, Thibodeaux collected 19 sacks and 35 tackles for loss, despite losing critical weeks to a pandemic and injuries. Cristobal cites Thibodeaux’s last four college games as his best stretch, with Oregon fighting for postseason position. In that month alone, he registered three sacks and wrecked offenses by demolishing double teams and, if it must be emphasized, playing with maximum effort.

Cristobal cannot remember when he first heard others criticize Thibodeaux’s desire and habits. Only that they did, and someone else did, and notions that make little sense to him started to gain traction. “Every year someone is subjected to it,” he says, pointing to recent examples from his Oregon program, which he departed after last season for Miami. Like Herbert, who overcame draft doubts to become one of the NFL’s best young QBs; and Penei Sewell, an offensive lineman who just finished a promising rookie year in Detroit. “I don’t know who these ‘experts’ are,” Cristobal says. “I have made it clear how exceptional those guys were. KT can be as good as [them].”

He sighs again. “I don’t get approached for that,” he says, meaning by interested NFL teams. “I’ve heard this. I’ve heard that. They should just ask me directly. But no one does.”

Cristobal builds out his argument. How would Thibodeaux have maintained his speed while growing from 213 pounds to 250 without desire? How would he have maintained his dominance in 2021 while dealing with a badly sprained left ankle that cost him games? Hadn’t he returned before he fully recovered, because he wanted to win?

Thibodeaux made All Pac-12 first team, twice; earned MVP honors in the conference title game as a sophomore (with 12 quarterback pressures!); and won a Rose Bowl. He generally did what most do to solidify their draft standing. But somewhere along that route, in the past few months, he also lost control of his own story. His college coaches could compare him to Von Miller, the bendy two-time Super Bowl champion who, like Thibodeaux, weighs in around 250. Friends could point to another premier pass rusher, Myles Garrett, who supposedly “took plays off,” according to evaluators. Garrett “only” made three Pro Bowls in his first five seasons, becoming a defensive force. Cristobal could say what Thibodeaux will confirm only when pressed, that the ankle injury bothered him far more than the public knew. Of course that lowered his statistical impact.

The coach wonders: Where’s the context? The nuance? Or, more simply, a single phone call?

There’s a mix of celebrity, scrutiny and endless fascination fueled by social media that Thibodeaux must navigate. It’s all very 2022. Speak too much, and you’re all about yourself. Speak too little, and you’re the star with nothing to say. Focus on a sport and hear how you lack other interests. Focus on a life, sport included, and you’re not focused enough. It’s easy to see why athletes like Thibodeaux wonder whether they can win. Why they want to control their narratives.

Collins believes strangers mistake Thibodeaux’s passion for arrogance. But as Thibodeaux steers the Mercedes toward his agent’s office, Klutch Sports in Beverly Hills, he pivots from that notion. He believes the environment is what changed the takeaway. Where much smaller classmates dealt with his size—“presence,” he calls it—in “a controlled setting,” there’s little he can control in the modern incubator of NFL draft analysis. Other students could get to know him. Those who doubt his NFL bona fides never will.

He, Kayvon Thibodeaux, the most direct source of all, would like them to understand a few things. 1) That he operates from a “place of consciousness,” every action performed with methodical intent. He’s the type of person who creates a 38-page PowerPoint presentation when asking Gaines to be his business manager; 2) that he worked his ass off, even if others now debate whether he cares; 3) he does care, more than any one of those critics would know; and 4) what he doesn’t care about is their opinions.

“Everyone fears the unknown, what they don’t understand,” he says. “Once people get to know me, they’ll see what I stand for, what I had to sacrifice. They’ll realize why I was meant to be in this position.”

He’s rolling, in the Mercedes and in spirit. “I had already been that person,” he says. “Before people thought I was that person. It’s like Jay-Z says, I’ve been a boss before you knew about it.”

His goal: to add context and nuance, closing the gap between the stories others tell and the one he wants to relay. Most of the rebuttal will center on how he plays, which he can control. Not how he might play, or might project. “Storytelling is everything,” he says, “and how you can re-frame a story to create controversy, or a villain, so to speak …” He trails off.

He’s right when he says that, “my real life is crazy enough to make into a movie.” It’s full of ideal narrative elements: action, controversy, obstacles overcome, dreams realized, relatability, belief. He could open the film on the day in his freshman season at Oregon when he had “The Chosen One” inked on his right arm to provide a daily reminder to “move with a purpose,” so that a family, he says, “that has never really done anything,” could broaden its horizons.

It’s broader, his vision. That’s why he’s meeting with Beats by Dre representatives. Why he listens to a presentation and weighs in on the design of the custom headphones the company will create. And why he’s sitting down with officials from the JREAM Youth Development Organization, which provides underprivileged children with resources and mentorship.

When he describes how focusing on the past is really only ego, he sounds stoic. When he praises Klutch founder Rich Paul and Paul’s close friend, LeBron James, for how they empowered those around them, he sounds wise beyond his years.

Thibodeaux, remember, is only 21. His story is probably on Chapter 4 or Chapter 5. But he’s not just telling a story; he’s learning how to tell it. Others might criticize him for leaving the NFL Scouting Combine early. He’ll point to the blistering 4.58-second 40-yard-dash he ran and the 27 reps he ripped off on the bench press. Asked how his life should, ultimately, be framed, Thibodeaux says it should be “frameless” but centered on his legacy. That story, concerns and all, is still in the rough draft stage. But he can see it taking shape, and what he wants will be what drives him toward the ending he alone wants to write.

Read more of SI’s Daily Cover stories here:

• Why Pass Rushers Will Rule the NFL Draft

• Aidan Hutchinson’s Rise to Potential Top Pick

• Behind the Spectacle of Kaepernick’s Comeback Tour