NFL Draft: Meet Matt Araiza, Punt God

If, last summer, you asked Matt Araiza whether he’d be sitting on this bench outside of the NFL combine, he probably would have said no. After all, he’d hit only five punts in college before the 2021 season. He might have had the same answer even if you asked him 48 hours before the combine, too, thanks to a stomach bug that caused him to delay his arrival to Indy (he refuses to blame it on Southern California staple In-N-Out Burger). But he made it, and now he’s a week away from likely being drafted, something that happens to only two or three specialists every year.

If a punting prospect can be considered can’t-miss, Araiza is just that. And in a draft without an elite quarterback, an argument can be made that outside of safety (Kyle Hamilton) and center (Tyler Linderbaum), Araiza is the best prospect in relation to the rest of his position group in the 2022 player pool.

Araiza is entering the NFL at a time when the ethos of what to do on fourth down is, albeit slowly, changing. As with any elite prospect, a double-sided question emerges: Is he ready for the NFL? And, is this NFL ready for him? Sports Illustrated spoke to Araiza and more than a dozen people, from team executives to coaches to elite special teams trainers, about his draft prep, and how the game 14 yards behind the long snapper changes from college to the pros.

If you have heard of Araiza, your entry point might have been what he calls his favorite punt, a “moonshot” that sonic boomed through the thin air in Colorado Springs, befuddling the Air Force returner as it sailed over his head before petering out in the opponent’s red zone. It traveled roughly 75 yards in the air. The box-score description is far too understated: “Matt Araiza punt for 81 yds.”

There was one punt of 80 yards or more in the NFL in 2021. The last time it happened before that was in ’13—and that’s with plenty of games played in mile-high Denver. Araiza did it twice in two weeks; against San Jose State, one week before Air Force, he hit an 86-yarder—albeit with more roll at the end.

We have an 86 yard punt... EIGHTY SIX (CC @RKalland) pic.twitter.com/KIi5d3VTTO

— CJ Fogler account may or may not be notable (@cjzero) October 16, 2021

On a team bus on the way home, Araiza’s phone was blowing up. People were starting to notice. His teammates alerted him to a tweet from former Colts punter and current media personality Pat McAfee, calling the 81-yarder a “piss missile.” And thus the legend of Punt God kicked into overdrive.

“Growing up playing soccer I was always a couple years ahead of everyone,” Araiza says. “When I was U-10 I could kick the ball like I was U-12. Then in high school, when I went out for the freshman team I wasn’t necessarily planning on doing it to just kick and punt; I was doing it to play football in general. I think my first-ever kickoff ever was a touchback, and the coaches kinda lost it at that. Just hearing the way they were talking about it made me feel like, O.K., I don’t think that many people can do this.”

In a high school game he punted from his own 20 and the opponent’s offense ended up inside its own 10. Araiza noticed there were many more scholarships available for football players than soccer players. He ended up getting offered by hometown San Diego State.

With power hitters in any sport, one of the first things you’ll hear people talk about is the sound of contact. The ball sounds differently off Shohei Ohtani’s bat. It’s the same with Araiza.

“It’s hard to describe other than when you hear it, it’s a unique sound,” San Diego State special teams coach Doug Deakin says. “[It] sounds simply amazing in terms of getting all of it. It’s a loud thump, the result of an explosion when two objects collide.”

Araiza didn’t start immediately as a punter for the Aztecs. He redshirted, then handled only placekicking and kickoff duties as a freshman and sophomore before taking over punting last season. In 2021, Araiza put together the most impressive power punting seasons in FBS history. He holds the record in average punting distance (minimum 50 punts) at 51.2 yards and hit 29 more punts than the previous record holder. Araiza acknowledges that when the punter is on the field, fans are typically looking at their phones or using it as a time to hit the bathroom. His fourth downs became appointment viewing.

“I kid you not, we’d make a couple first downs and we’d be at the 50 and we’d stall out, and we would joke, ‘Well, damn, now we’re gonna ruin Matt’s punting average,’” SDSU athletic director J.D. Wicker says. “It’s one thing to get excited about quarterbacks throwing 80-yard bombs and all this different stuff, but it’s like, ‘All right, Matt’s on the field, we’re on the 10-yard line; let’s see how far he can kick it this time.’”

By the time the season ended, he’d been on national radio shows and had a feature on College GameDay. He won the Ray Guy Award and earned unanimous All-American honors.

Soon after San Diego State’s bowl win in December, Araiza declared early for the draft—a rarity for a punter—and began the transition from player to prospect. He works with local Southern California trainer Cody Smith and former Chargers kicker Nick Novak.

The first thing to understand about Araiza is he’s not just a twig in pads. He’s 6' 1", 200 pounds and ran a 4.68 at the combine; Deakin says he would run with the skill-position group during offseason conditioning. He’s described by multiple people as a tremendous athlete, making five tackles covering his own punts (Novak is trying to rein that part of Araiza’s game in as to preserve his longevity). He’s a football player who happens to be able to punt, and that’s part of the reason he didn’t punt early on at SDSU.

“Technically what he had to work on was his hands,” Deakin says. “A lot of times he’d catch it from the snapper like a wide receiver. His fingers were pointed up, which, yeah, that’s how you catch a football if it’s above your waist, but then he’d have to flip or manipulate the ball to turn it, then put his hand underneath to be able to drop it in the punt.”

He was outdistancing the other punters on the roster from Day 1, but his operation time—a special teams term for time from snap to when the ball actually leaves his foot—was too slow and his hang times were too short.

Despite Araiza’s power proficiency, to make it in the NFL you have to be a more well-rounded player. What was an optimal punt at San Diego State is now different as he trains for the NFL; he’s had to adapt, just like he did at SDSU. That’s what Smith and Novak have him focusing on.

The second thing to understand about Araiza is he’s a punting wonk. Be careful asking him about his craft unless you’re prepared to get a lengthy crash course on the topic. He’s shortening his steps to get more under the ball at impact, increasing his hang times. He’s shortening how far he drops the ball from his body as well.

“The swing path is like a crescent, so [dropping it closer to the body] changes where it is in that crescent,” Araiza says. “When you’re hitting the ball, the ball’s coming out more as a line drive, whereas the shorter the arms are, the ball gets a lot higher.”

He describes hitting a good punt as understanding where the ball is in space and matching your foot up to it as the ball moves on the axis of direction (right, left, up or down). Even though the ball is dropping maybe 12 inches in the air from his hands to his foot, little things can change where it goes as it travels downfield. A drop to the right of his foot means the ball is likely going to end up to the right of his target.

“A detail a lot of people don’t know is, when you punt you drop the ball and it spends time in the air; and if it’s really windy the wind will move the ball,” Araiza told reporters at the combine. “You can lower the drop, giving it less time in the air for the wind to move it.”

Even the ball itself—the feel of it—impacts how Araiza punts. An NFL football is smaller and slightly less round than a college ball, which, he describes as weight more on the outside of the ball versus the bladder. Another complexity is that, for kicking plays, the NFL uses special “K balls” that are generally slicker and newer than the rest of the balls used during a game.

“It’s definitely easier to spiral the [NFL] ball,” Araiza says. “Without a doubt they’re better. Better for field goals, better for punting, better for kickoffs, better for everything in my opinion. Just different. When you’ve taken 10,000 reps with one ball switching to another ball, it does feel a lot different.”

The spiral matters particularly for Araiza because he’s lefty, a small edge that impacts returners. Legendary kick returner Dante Hall once described catching a punt from a lefty as “a Roger Clemens curveball coming from the sky.”

Araiza mostly avoided hitting NFL balls until he started preparing for the draft. He might not get up to 10,000 reps with an NFL ball before he starts the 2022 season, but he’ll have plenty of prep. His work with Novak and Smith involves hitting 50 to 70 full punts a day, as many as five days a week. Sometimes Novak has to shut him down because, as Araiza admits with a smile, they get excited during a day’s work. That’s where the third thing to note about Araiza comes into play: He’s a workout warrior.

His days are long now, and yet he’s never late according to Smith, who runs a training facility near where Araiza grew up in Rancho Bernardo, Calif. Smith likes to see what time new trainees show up to their first workout, just to get a gauge on their work ethic. Araiza was there 45 minutes early for Day 1 and hasn’t been late one time, according to Smith.

“With a guy as explosive as Matt is, he’s just naturally an insane athlete,” Smith says. “I was amazed because he came to me and picked everything up like that. He walks in the door, and I give him one thing to work on and usually sometimes it’d take months for people to kinda figure it out. He’ll figure it out in a couple sets, and it just clicks for him.”

Smith estimates he works with 30 to 40 NFL specialists in a given offseason. He, along with Novak, have made Southern California a training mecca for NFL specialists.

Smith works with golfers, baseball players and fighters as well. While you might think golfers and punters aren’t the classic definition of an athlete, there’s connective tissue across many great athletes. It’s how they use rotational force and harness core strength to make what they do look effortless.

Just like how a quarterback can launch a ball in the air 60 yards, a fighter can knock you out with preternatural punching power, or a golfer can drive the ball over 300 yards, so can Araiza launch a ball through the air by tapping into his oblique sling, a term used to describe the musculature that runs from one shoulder to the opposite hip on either the front or back of your body.

“Everybody I’m training I basically preach getting them to engage the core and glutes for a full hour so they can always find that connection pattern,” Smith says. “Even as they fatigue they can still find that connection, and you get a little more control because it’s also in charge of accelerating and decelerating your body. So if guys feel like they’re just hammering the ball all the time, it’s kinda just giving them a little more torque and control.”

Even if Araiza’s leg starts to tire, given the amount of punts he’s hitting in a day, it’s important for him to not lose the connection with his core and his glutes. It also helps him stand taller and keep his posture as he’s going to punt. He felt like he was having to make compensations in his swing, now he’s doing things he didn’t have the ability or the strength to do before.

“It’s more efficient with getting the ball high into the air. In a golf swing you want to stay simple; you get too much crunch and all this other stuff—too many moving parts,” Araiza says.

More height on his kicks means more hang time, and in the NFL the game is much more about hang time. The hang time concept is probably the biggest adjustment Araiza has had to make. Deakin says when NFL teams inquire about Araiza, the biggest question mark they have is whether he can hang it.

His average hang time in college was 4.0; now it needs to be around five seconds. Like a home run hitter asked to no longer swing for the fences, Araiza acknowledges that his perfect ball is now 50–55 yards with a 5.0 hang time.

“Most coaches are gonna say give me a 45-yard ball, 5.0 [hang time] and we’ll put our defense out there and live to see another day,” Novak says. “That’s job security for both the punter and the coach because they’re running down there and calling a fair catch most of the time. But if you’re backed up and the line of scrimmage is on the minus-two, you’ve gotta get this sucker off quick. He has the ability to kick it across the 50 past the 40 maybe, and that’s when the crowd’s going crazy; and the ball hits the ground and the ball’s going inside the 10.”

Among the ways they drill hang time is wheeling a goalpost onto the middle of the field. If Araiza cleared the goalpost, the hang time would naturally climb because the ball is coming off his foot on a more vertical trajectory. If he didn’t, he risked getting a face full of football.

2022 NFL Draft Prospect Matt Araiza.

— Nick Novak (@8nicknovak) January 6, 2022

(45/5.53) LOS -45

Hang-time “PR by a lot”

Sky is the limit!

1% Better@JLSports3 @AztecFB #novakkc pic.twitter.com/d68xKFecYY

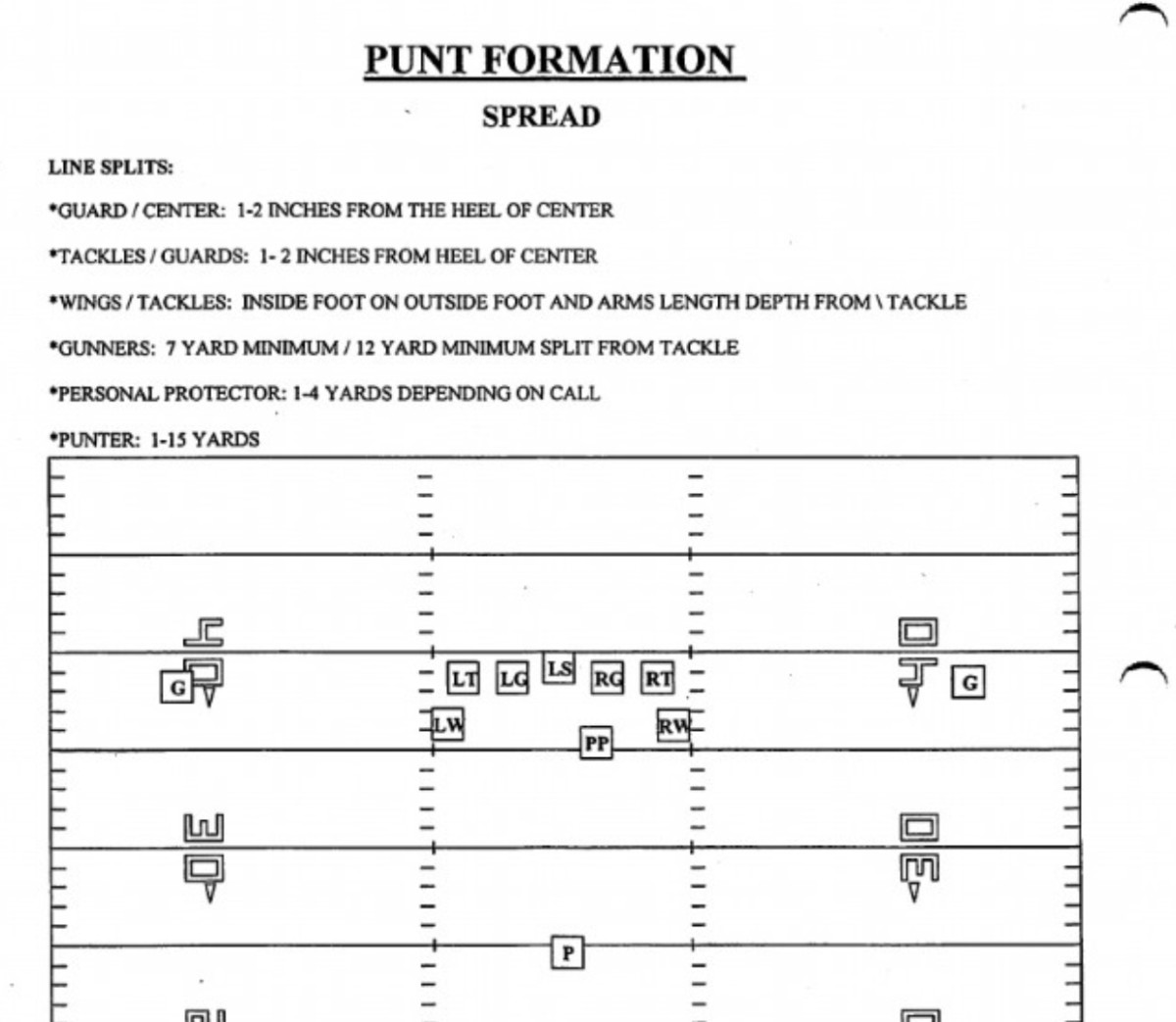

The mechanics of an NFL punt also affect what NFL teams want. There’s more creativity in college and more formation variety. In the NFL, you’re mostly going to see a punt formation like this: two gunners, two wings, four offensive linemen, the personal protector and the long snapper:

In the NFL, only the gunners can cross the line of scrimmage before the ball is kicked. In college, everyone can free release at the snap and head downfield. So if you line-drive a punt 65 yards in the NFL, the coverage team isn’t going to be close enough to the returner. And if you give a return man like, for instance, Tyreek Hill, room for a head start, you’re going to have a bad time.

It’s also why directional kicking matters more as well. If the ball’s on the left hash, keep it between the top of the numbers on the left side of the field and the sideline, perhaps the ball goes out of bounds. If you miss-hit it and it travels too far into the middle of the field, bad things can happen.

NFL punters have gotten better over the years at producing balls that aren’t being returned for touchdowns. There were two punt-return TDs during the 2021 season, in contrast with 18 a decade ago. It’s part of why, despite the fact that he punts, Araiza would actually like to change the return rules to the CFL rule set, which encourages returns.

“I like their rule set where they give the returner a five-yard circle around him, but it makes more returns possible; and I think that would be a fun aspect to add to NFL punting,” Araiza told reporters at the combine. “I think any opportunity to increase how much fun people have watching the game they should take it.”

Football still lags behind other major sports in the analytics movement. Special teams would seem to be one area where analytics could be at the forefront, the one part of the game where you’re trying to gain a strategic edge on the game’s margins. In reality, not so much.

While the discourse in golf’s distance boom, for instance, relies heavily on new-age metrics like ball speed and club speed, and baseball seems transfixed on exit velocity and launch angle, there isn’t really accessible data on punting beyond the old reliables: distance and hang time. Even Novak and Araiza aren’t working with data like the spin rates for his punts.

Regular metrics like average distance and net punting average (Araiza finished seventh in FBS in that) tell one story, but advanced metrics can add further context to how good he is.

Pro Football Focus researcher Conor McQuiston found that by using the number of points an offense could expect to score following an average punt, Araiza saved his team three touchdowns over the course of the season. If he’s able to save an NFL team two, it would make him one of the best punters in the league.

This was extremely impactful specifically for San Diego State, which ranked 92nd nationally in offensive SP+ (a tempo- and opponent-adjusted efficiency rating) and 12th in defensive SP+. When considering a punt as the first defensive play of a series, Araiza’s impact for a team that, despite finishing 78th in scoring offense (27.4 points per game) still went 12–2 and played for a conference championship, was significant.

“In the research I’ve done, at least in the PFF era [since 2016], he’s the most impactful, most valuable punter we’ve seen by a pretty decent margin,” McQuiston says. “Michael Dickson in 2016 comes pretty close; he’s easily the best punter in the FBS that we’ve seen, and it’s not particularly close.”

With all the length on Araiza’s punts, there is always the threat of the touchback. Araiza led the nation with 15 of them in addition to being second in the nation in punts inside the opponent’s 20. According to Mike Lounsberry, who submitted a research project to the NFL’s Big Data bowl statistical competition—which was centered on special teams this year—Araiza’s 2021 was one of the best power punting seasons of all time.

Football is, at its core, a methodical land-grab, lacking the fluidity of other American sports, and thinking of punting and its value to the team as a strictly territorial exercise can change the way you look at it.

Data shared with SI showed that on punts 60 yards and in (where a touchback is not necessarily the optimal outcome), the NFL average touchback percentage is 14.8%. Commanders punter Tress Way had a touchback rate of 30.4% on those punts, worst in the league; Araiza’s touchback rate on those punts was 32.3%. But again, what ball was Araiza being asked to hit? Lounsberry also pulled data on the average field position following any punt. The NFL average in 2021 was 74.9 yards from the spot to the opposing end zone. Dickson led the league at 79.1. Araiza left offenses with an average of 80.6 yards.

It’s impossible to divorce punting from the broader fourth-down discourse in the NFL. It is true that the NFL has never punted less, on average, per team. But despite moments like the Chargers going for it from their own 19, or the Ravens going for the win on their side of midfield against the Chiefs, the belief that teams are going for it more on fourth down are, in McQuiston’s words, overstated.

“It’s not like basketball where you see every team slowly adapting at roughly the same rate, We’re gonna shoot more threes and we’re gonna really stratify where we take our shots,” McQuiston says. “It’s more like once a team gets a forward-thinking coach or GM, then the team buys in then; they get dragged up.”

This doesn’t mean that Araiza has to go to a bad team, or a luddite for a head coach, in order to be maximized. In fact, in a future where teams are punting less often, but particularly less often from 60 yards and in, a long-ball punter can present more value.

“Football’s not gonna change for a while,” says Eric Galko, director of football operations and player personnel for the East-West Shrine Bowl. “If you’re at your own 40, you’ve got to punt if you’re past fourth-and-4 or -5. Everyone will tell you that, so having the guy who can do it the best, he’s able to allow you to make a mistake on defense. It’s a negative first down for a team, and that’s so valuable in terms of analytics as well. Punters are not gonna go away at all, especially ones that can boot it like him.”

Galko, who runs college football’s longest-running all-star game, didn’t get a chance to invite Araiza because he wasn’t a senior. But Galko still has high praise for Araiza, calling him the best punting prospect since Ray Guy, the namesake of the punting award Araiza won last season and the only pure punter in the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Perhaps it will disappoint his devotees, but Araiza doesn’t plan to continue kicking field goals at the next level; it was the double duty that added yet another reason he shined last season. If the opportunity presents itself because of injury he’ll step up, but he’s been telling teams he sees himself as a punter and a kickoff specialist. It may be the holy grail of penny-pinching roster-building, but the tax it can put on the body and the risk of injury don’t make it worth it for pro teams.

Where Araiza will be drafted next weekend is anyone’s guess, although it’s easy to make an approximation of early on in Day 3. Even how teams scout punters is specialized. Teams often defer to their special teams coaches in the scouting process more than at other positions because so much technique is involved.

“I would say we’re collaborative in everything that we evaluate, but I would say it’s a different level when we’re talking about kickers and punters and long snappers because it’s such a specialized skill set,” Falcons GM Terry Fontenot says.

In research conducted by The Athletic, since the NFL draft was cut from 12 rounds in 1993, the average pick used on a punter is No. 168 (fifth round). Bryan Anger was selected by the Jaguars in the third round of the 2012 draft, making him the earliest selection (70th) since Todd Sauerbrun, who was taken in the second round (56th) back in 1995.

“This is a really special time for me because I’m still living back home,” Araiza says. “I still get to see my friends back home, but I’m also getting to live this NFL life, training and working with some great guys between here and my pro day. I’m gonna enjoy these four months because soon I’m gonna be leaving San Diego forever.”

There are local kids who know who he is after playing for the only football show in town, and there’s some hope within the SDSU community that it’ll be good for recruiting to see a local guy reach stardom by staying home. The hometown kid pulled off what may be more astounding than any 80-yard boot; he resonated on a national level and left an indelible impact on college football by making fourth down matter even when the offense was jogging off the field.

In the process, Matt Araiza went from punter to Punt God. The deification process is complete; now it’s on to making believers of the NFL.

Read more of SI’s NFL Draft stories here:

• Why Pass Rushers Will Rule the NFL Draft

• Aidan Hutchinson's Rise to the Top of the Draft

• Kayvon Thibodeaux Hears His Critics and Has a Plan