Inside Bill Belichick’s Final Season As Patriots Coach and What Led to His Ending

Bill Belichick and Robert Kraft approached the podium inside the New England Patriots’ team meeting room Thursday with the look of two men at peace. Maybe it was because each guy got what he wanted—Kraft the elegant conclusion to the Belichick era and Belichick the freedom to go write the last chapter to the NFL’s greatest coaching legacy somewhere else.

But the idea that the two reached this place—where the right decision clearly for everyone was to turn the page—just this week would defy any sort of logic you want to apply to the situation.

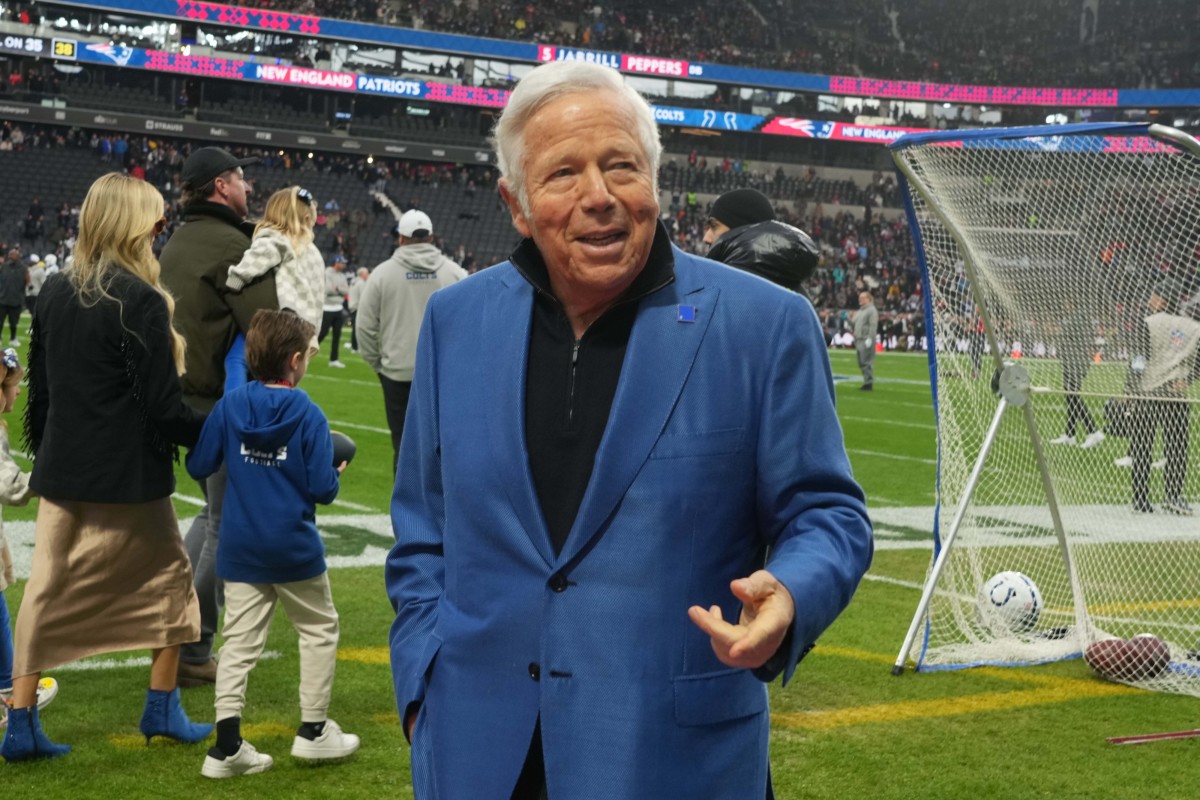

Two months ago the Patriots landed in Germany with their season circling the drain, and Kraft hoping he could salvage yet another championship iteration with the Belichick era hanging by a thread. New England was 2–7 with a struggling young quarterback, a roster devoid of much hope for the future, a divided coaching staff and an owner who’d looked forward for months to the opportunity to bring his brand to a country where he’d worked hard to gain a foothold.

Kraft told anyone who would listen what a big game it was for him personally. He said it at a fan rally and expressed it to his team at the Saturday walk-through, stepping in to address the players in a way he rarely would in the middle of the season. A day later the Patriots didn’t just look bad. They looked like a dysfunctional mess.

An undermanned offensive line, sans embattled left tackle Trent Brown, gave up five sacks. The tenuous situation around troubled corner Jack Jones boiled over. Mac Jones threw a hideous interception at the end of the game, giving the staff another sign that his confidence was completely shot, and was benched. And the game effectively ended with Bailey Zappe throwing another pick on a badly botched fake spike play.

The network cameras showed Kraft in an oversized coat in a suite looking like someone out of answers. But those around him believed that he did have one: The time had finally come to pull the plug—on a coach who will go down as the greatest in NFL history—and start anew.

The past two months have given everyone plenty of time to think about how the ending that arrived Thursday would play out. The Patriots showed life at the end of the season, and Belichick very clearly had not lost the team with wins over the Pittsburgh Steelers and Denver Broncos, and competitive losses to AFC contenders in the Buffalo Bills and Kansas City Chiefs.

Those wins, though, really showed what everyone in the building already knew—that Belichick could still coach.

The rest of it explains why Kraft had to say goodbye Thursday.

The problem in New England the past couple of years started with people—and how Belichick’s machinelike ability to develop them behind other quality people slowed in recent years.

The 2014 Super Bowl championship team is a great example of what the Patriots were capable of on the field.

Darrelle Revis and Brandon Browner were the corners, with Logan Ryan and Malcolm Butler developing behind them. Shane Vereen was the third-down back, and James White was behind him. Sebastian Vollmer was the right tackle, with Marcus Cannon as his backup. Josh McDaniels had Brian Daboll on his offensive staff. Matt Patricia had Brian Flores and Patrick Graham with him on defense. Joe Judge was Scotty O’Brien’s No. 2 on special teams.

Four years later—as the Patriots won their third title in five years—cracks in that foundation were showing. The team was forced to hold on to older players later into their careers. Meanwhile, coaches such as Patricia, Daboll, Flores and Graham were off to advance their own careers, and a gaggle of scouts were frustrated that they weren’t being heard bolted for greener pastures.

The draft was at the heart of the issue, and 2019 provided a flash point for folks on the personnel side. Before that draft, Patriots scouts were high on the South Carolina Gamecocks’ Deebo Samuel and Ole Miss Rebels’ A.J. Brown. The two came to Foxborough together on a visit and had been traveling together all week. As such, they had a good, jovial ability to poke at each other and laugh together, and Belichick was leery that they weren’t taking the visit seriously enough.

Conversely, Arizona State’s N’Keal Harry had crushed his visit and, combined with recommendations from confidants—Sun Devils coaches Todd Graham and Herm Edwards—Belichick started to veer from his own scout’s recommendations. It was—to the scouts—another example that they weren’t being heard and that Belichick was taking the information he’d gathered instead of what they’d spent months and months compiling.

Picks such as Harry and left tackle Isaiah Wynn left New England without answers at premium positions. The selections also left the Patriots stuck trying to fix mistakes, chasing the first-round investments they’d made, rather than just ripping off the Band-Aid and starting over.

As such, New England entered the 2023 season with this damning piece of history: The Patriots hadn’t given a homegrown top-100 draft pick a second contract in six years, with the last deal going to ’13 third-rounder Duron Harmon. The last first-rounder to get an extension was Dont’a Hightower in ’12, a great player at one time and Super Bowl hero who, not coincidentally, was one of the players the Patriots had continued to pay until the wheels fell off.

All of that was coming to a head going into 2023, with Kraft’s stated goal of getting the team’s first playoff win since Super Bowl LIII on the record in March and a roster ravaged by the team’s draft slump not close to being in position to carry that through.

Perhaps the strongest sign of trouble going into 2023 was what the Patriots had to do to get by at those premium positions. They brought back Brown, and all of his baggage, to play left tackle. They signed JuJu Smith-Schuster, damaged knee and all, to spackle the Harry damage, just what they’d hoped Brown would do for the Wynn miss. They stuck with Jack Jones through gun charges (eventually dropped) even after all of the issues he’d had in college caused him to drop to the fourth round in ’22 and after they’d suspended him as a rookie.

It was the opinion of many in the organization that guys such as Brown and Jack Jones would’ve been long gone in days gone by, with rosters built strong enough to sustain such losses or a quarterback who could always make up for it. Along the same lines, where in the past the Smith-Schuster signing would’ve been a calculated gamble, the 2023 Patriots were actually counting on him to come through.

Meanwhile, the attrition in coaching was felt with a small, patched-together staff that was working day to day and struggling to get along.

Which led to problems that didn’t go away …

• Bill O’Brien returned in January to clean up all that went wrong through the unorthodox decision to have Patricia and Judge run the offense in 2022. Belichick asked O’Brien upon his hire if there was anyone he wanted to bring with him, and O’Brien hired Will Lawing, who he’d been with at Penn State, Houston and Alabama. He and Belichick then flew to Las Vegas for the East-West Shrine Game, and interviewed Oregon’s Adrian Klemm and Bills assistant Ryan Wendell for the line coach job, eventually settling on Klemm.

O’Brien inherited the rest of the offensive staff and wasn’t given quality control coaches. When Klemm got sick and took a leave of absence before the trip to Germany, a group already stretched thin—without lower-level assistants to do ground-level stuff such as breaking down tape—started to snap. O’Brien, Lawing, Troy Brown, Vinnie Sunseri, Billy Yates and Ross Douglas effectively had to do everything.

Meanwhile, tension grew on the staff, with Belichick leaning more into the offense. Jerod Mayo’s status as de facto coach in waiting caused some to start to pick apart how the former player, who was always popular in the locker room, was carrying himself. Douglas departed in early January for Syracuse and wasn’t seen as carrying the rope—with the receivers’ play being a problem. Klemm came under internal criticism but had voiced frustration with the talent.

Everyone was bracing for the end, while the ultra-disciplined Belichick conducted business as usual, even holding his regular draft meetings Fridays with the personnel guys to plan for next April and discussing extensions for his coaches.

• Hanging on to guys such as Brown and Jack Jones contributed to a culture—built carefully over decades—starting to fray.

Jones was suspended in 2022 for missing and being late to rehab sessions after he was hurt and talked back to Belichick when he was called out on it. He remained on the roster into the season. Then, in Week 9, he and J.C. Jackson were late to the team hotel before the Commanders game and benched as a result.

The next week, in Germany, everything came to a head. According to multiple sources, Jones had been upset about losing his starting spot, and he was visibly angry toward players and coaches as he was used sparingly in the first half. That anger boiled over in the locker room, where teammates tried unsuccessfully to calm him down. He sat out the second half of the game and was cut days later.

Meanwhile, Brown’s attitude was a constant problem, with one coach describing his approach in practice as “you can make me work long, but you can’t make me work hard.” Once free agent Calvin Anderson got sick in the summer, the staff saw Brown become more emboldened to do things his own way, knowing that the team’s other options (free-agent pickup Riley Reiff, whose legs were clearly gone, cutdown weekend pickup Vederian Lowe and veteran journeyman Conor McDermott) left him with leverage to act that way.

Coaches, staffers and teammates were baffled when he got new incentives in his contract in late September—perhaps in a last-ditch effort to get him on board. The common refrain, even at that early juncture, was Why is this guy still here? The simple idea that he’d be rewarded rubbed players the wrong way.

And with all of this happening, the few remaining torchbearers of the dynasty, guys such as Matthew Slater and David Andrews, felt the weight of trying to prevent a looming trainwreck.

• The quarterback situation only exacerbated all that had gone wrong.

In 2021, Belichick liked Alabama’s Mac Jones and Stanford’s Davis Mills, seeing Jones as the best option at the position in the class apart from Clemson’s Trevor Lawrence. And while the Patriots didn’t love Jones, who had his share of physical limitations, they knew they needed to do something at the position after how going into ’20 without a real quarterback plan played out.

They’d agree on taking Jones with the No. 15 pick rather than the alternative, which would’ve been drafting a position player there, and coming back and getting Mills either in the second round, or with a trade up into the bottom of the first round. And while they were on the clock, there wasn’t much discussion about doing anything else.

Things went fine during Jones’s rookie year. He had his ups and downs, and there was a fair amount of handholding to guide him along—with McDaniels at times helping him read coverages and make checks through the headset—like Sean McVay once did for Jared Goff in Los Angeles. Belichick was optimistic internally on Jones coming out of the year, even with McDaniels off to Vegas.

Things came undone with Judge and Patricia running the offense in 2022. But most Patriots people felt like, with O’Brien aboard, the “real” Mac, the one from ’21, who could at least drive the bus at quarterback, would resurface.

Instead, Jones came back with a confidence that some teammates, coaches and staff saw as false bravado. It was bolstered with Zappe struggling and the team deciding not to trade up for Kentucky’s Will Levis in April, which had been at least a point of discussion.

Jones’s irrational courage would, in time, crater, with crushing mistakes that showed up in early losses to the Saints and Cowboys repeated in practice—to the point where teammates on defense were calling them out. And Zappe kept fighting to show a staff that had determined he wasn’t good enough—cutting him in August and bringing him back after—that he could do the job, smirking to coaches as he completed more difficult throws on the practice field. The competition made things icy in the quarterbacks room, too. In 2022, Zappe, who was a rookie, would watch tape in the receivers room just to get out of there, according to sources.

On the field, the result was Jones playing outside of himself, with that bravado (false or otherwise), and Zappe fighting to get another shot. Zappe earned that shot the same way he did the year before, simply by showing that he’d go out there and follow the coach, winning over Belichick, who’d grown tired of Jones’s attitude and lack of leadership qualities for the position.

One staffer looked back at the Germany experience and the way Kraft carried himself in the aftermath in simple terms—“I think he was embarrassed.”

And in a vacuum, the problem wasn’t Belichick himself.

It was the decisions he’d made that left the foundation of what he built so susceptible.

The last month of the season showed a team playing with pride and for one another. The wins, one over a playoff team and the other over a team that was in the race into New Year’s weekend, proved that Belichick on the sideline on Sundays was still more than capable.

The problems the Patriots had were separate from that and built up over years, not weeks or single games. It was the makeup of the staff. It was the makeup of the roster. It was a group of players who weren’t good enough, and objectively bad in a few critical spots, with a quarterback who probably shouldn’t have been drafted in the first round writing checks that his body couldn’t cash.

The buck on all that, and everything else in the Patriots’ football operation, stops with Belichick, as it has for over two decades.

“F--- yeah, he can,” said one staffer Thursday after the news became public.

It was everything else that added up to this ending for the greatest coach in NFL history.