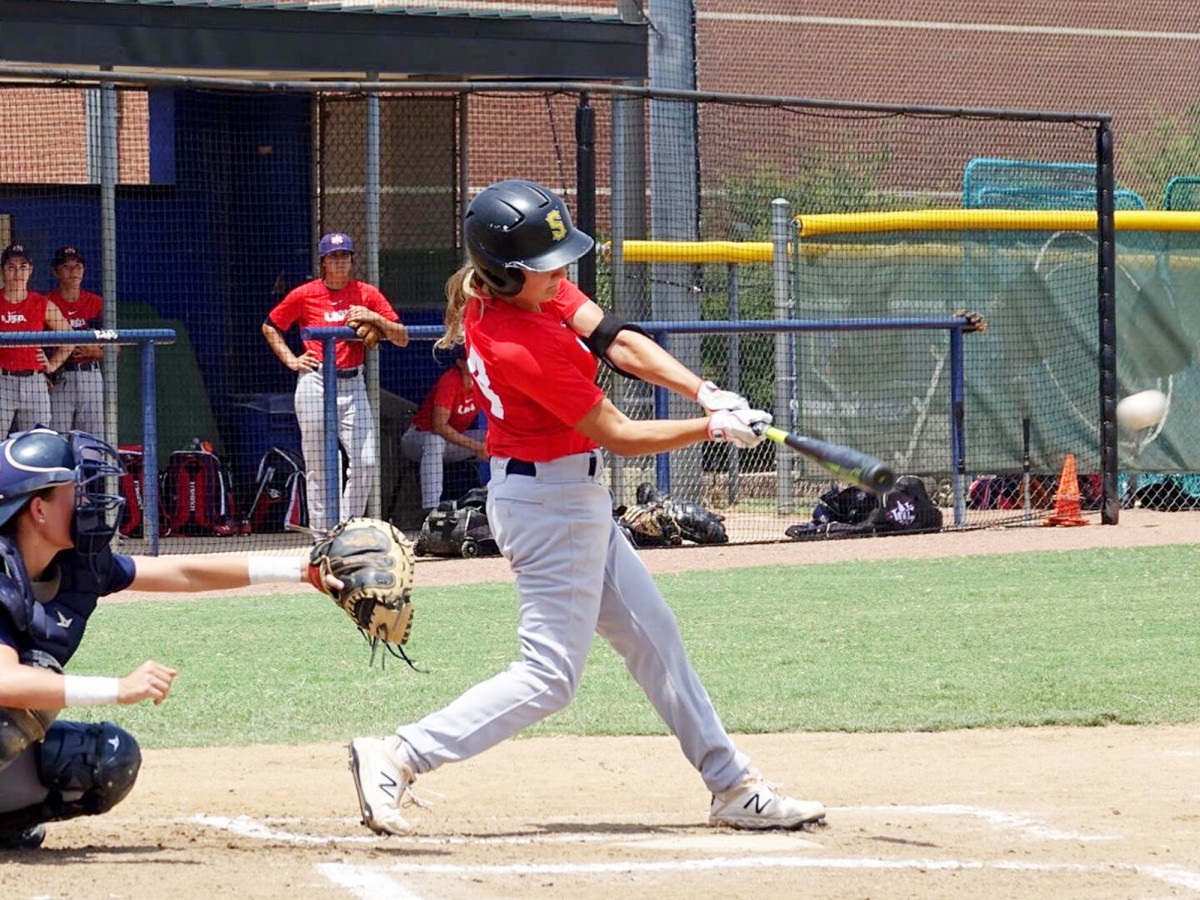

Breaking the Grass Ceiling: More Women Are Playing College Baseball Than Ever Before

After playing baseball for two seasons on the JV team at North County High School in Glen Burnie, Md., Skylar Kaplan was confident—as were her teammates and her summer travel team coaches—she was good enough to make the varsity squad.

Despite her past performance and a strong showing at tryouts, Kaplan was cut her junior year. It had nothing to do with her ability on the mound or in the batter’s box.

“One of my friends on varsity told me they overheard the head coach say he’d never let a girl on varsity,” Kaplan says, “and he didn’t want to be the laughingstock of the county.”

Kaplan was heartbroken, but she continued to train and play with her summer club. Even though she knew that she still had no chance to make the high school team, Kaplan tried out again her senior year.

“I wanted to go out there and prove that [the coach] wasn’t going to stop me from playing,” she says.

Kaplan was cut again, but she didn’t give up on the game she has loved since she started playing at 5 years old. After graduating from high school last spring and playing summer ball, Kaplan enrolled at Anne Arundel Community College in Arnold, Md. She showed up at fall baseball workouts and made an immediate impression on the school’s new head coach. This spring, Kaplan made the Riverhawks baseball roster, becoming the only woman to pitch in the National Junior College Athletic Association. While facing top Division I NCAA prospects, the lefthander struck out 11 batters in 11 2/3 innings of work in her first season. Her coaches and teammates welcomed her.

“I knew a few guys on the college team already from playing with them or against them throughout the years,” Kaplan says. “The ones who had no idea who I was, once they saw me hit and pitch for the first time they were like, ‘O.K. She’s good. That’s all I need to know.’ They’ve all been great to me and have been very supportive.”

Kaplan, one of a handful of women playing baseball at the collegiate level, is part of a select but growing group that also includes Kelliann Jenkins, a pitcher for Chatham University in Pittsburgh; Jazzmine Rivera, a pitcher for Harry S. Truman College in Chicago; Marika Lyszczyk, a catcher and pitcher for Rivier University in Nashua, N.H.; Beth Greenwood, a catcher for the University of Rochester; and Luisa Gauci, a second baseman who has signed a letter of intent to play for Green River Community College in Auburn, Wash. Each of them is the only woman on their respective college teams—as they often were on teams at every level. They’ve followed similar paths through the baseball ranks, and have grown accustomed to standing out and being scrutinized.

“I have had the spotlight on me since I was a little kid,” says Greenwood, who competed against boys through Little League, middle school and high school. Last summer, she became the first woman to play in the Sunset Baseball League, one of the oldest amateur leagues in the country.

“Everyone is going to look at you, whether you like it or not,” she says. “You feel like you have the weight of the world on your shoulders and sometimes when you’re playing you feel like you’re playing for all of the girls and women in baseball. It can be hard to separate that and remember that you’re just a baseball player like anyone else. But having all of those eyes on you is a privilege. It is a privilege to be here and have these opportunities because I didn’t know this was possible when I was younger.”

Often, the toughest battles girls and women who want to play baseball face aren’t against opposing batters but stereotypes. One reason Greenwood initially didn’t think college baseball was an option is that she—like many other girls—was pressured to play softball instead.

“Even when I was a little kid, people pushed me to switch over,” Greenwood says. “People would say, ‘You won’t be able to play baseball in high school. There are no opportunities for girls to play baseball in college.’ ”

Lyszczyk played both baseball and softball until middle school, when she decided to put all her focus into baseball. She believes girls are pressured to go into softball and stay away from baseball because of social norms, as well as the challenges players can face being the only girl on a team.

“We’re taught that girls play softball and guys play baseball,” Lyszczyk says. “My mom assumed that I wanted to play with the girls, so she put me in softball. Some girls love baseball and don’t want to play softball, but they also don’t want to play in a super-male environment. A lot of times girls switch over to softball because they don’t feel comfortable with the guys or feel intimidated by them. But you shouldn’t have to switch to softball. Baseball and softball are two very different games.”

When she arrived at Truman College, Rivera inquired about the school’s baseball tryouts. She was given the name of the coach and directions to the site of the tryouts—but when she arrived at the field she realized that they had sent her to softball tryouts instead. When Gauci, who grew up in Australia, started looking at schools in the United States where she could potentially play baseball, the recruiting services she contacted refused to send out her baseball profile and only offered to help her get scouted for softball.

“The softball coach at my high school told me I was going to have to switch to softball at some point, especially if I wanted to play in America,” Gauci says. “Even now, some people ask me if I’m interested in switching to softball and mention that there would be a lot more scholarship money for me in softball. The money and getting to play at a Division I school entices me, but I am so passionate about baseball and I love it so much that if I played softball at a Division I school, I would just be mad that I’m not on the baseball team.”

The first woman to play NCAA baseball was Julie Crouteau, who made the St. Mary’s College of Maryland roster as a freshman walk-on in 1989. Since then, 15 other women have followed in her footsteps. Jodi Haller was the first woman to pitch in a college game, for St. Vincent College in Latrobe, Pa., in '91, and then the first woman college player in Japan’s history when she suited up for Tokyo’s Meiji University in '96. Erin Marks played outfield for Oberlin College in '94. Ila Borders became the first woman pitcher to start a men's NCAA or NAIA college baseball game, playing for Southern California College from '94–96 before transferring to Whittier College for the '97 season. Molly McKesson earned a partial baseball scholarship to Division II Christian Brothers University in Memphis, where she pitched from 2005–08.

Baccellieri: Growth of a New Game: Inside the Women's Baseball World Cup

Australia's Christal Fitzgerald became the first international woman to play NCAA baseball. The pitcher/infielder played for Daniel Webster College from 2007–10. Marti Sementelli earned an academic/athletic scholarship to play baseball for Montreat College, an NAIA school in North Carolina, in '12. Ghazaleh “Oz” Sailors pitched at Division III University of Maine at Presque Isle from '12–15. Sarah Hudek played at Bossier Parish Community College in '16, and Ashton Lansdell played at Georgia Highlands College in '20.

Many of the women who play, or have played, college baseball credit Baseball For All—an organization founded by Justine Siegal, the first woman to coach for an MLB team—for paving the path for them. Motivated by her own experience, Siegal has made it her mission to develop playing opportunities for girls and women.

“When I tried to play baseball in college—at a Division III school with a no-cut policy—they told me I couldn’t play because they ran out of jerseys,” Siegal says. “It crushed me and my dream. I had no one to turn to and had no idea what I could do about it. You can only hear the same story so many times of girls quitting baseball because they need to get a softball scholarship before you feel the need to fix that problem.”

So she founded Baseball For All in 2012. It started with one all-girls team playing against boys in Cooperstown, N.Y. This July, 48 teams—featuring hundreds of girls from all over the U.S., Canada, Australia, France and South Korea—will convene in Aberdeen, Md., for Baseball For All’s sixth national tournament.

Siegal says that her organization also supports coed college baseball—she recently reached out to schools across the country, asking if women were allowed to try out for their men’s baseball team, and heard back from more than 130 programs. But her next goal is establishing intercollegiate club baseball for women, which she sees as a necessary stepping stone to women’s baseball becoming an official collegiate sport. To kickstart the initiative, Baseball For All is hosting a Women’s College Baseball Invitational this August at Centenary University in New Jersey. The tournament will provide an opportunity for rising high school seniors and college students to compete against one another.

“We are hoping to inspire some of the college students to go back to their own campuses and start a team of their own,” she says. “We are going to talk to them about how they can start a team and mentor them through the process.”

Kaplan thought she was the only girl playing baseball before she attended a Baseball For All tournament and found an entire community of players just like her.

“I didn’t know that there were so many other [girls] who were actually going through what I was going through,” Kaplan says. “When I saw all the others it was inspiring to know that I wasn't alone. We're all the same and we all have similar backgrounds.”

While the current crop of college baseball pioneers all agree that more opportunities for girls and women to play baseball is the goal, not all of them believe that leagues separated according to gender are the best option.

“I would rather see it go in the coed direction than separate leagues,” says Jenkins, who’s never encountered the same level of negativity or resistance that some of her peers have while playing baseball. “I think it's really cool when a girl puts in the work and then is able to have success playing with the guys. Girls should be able to play in separate leagues if they want to, but then that gives validation to the argument that girls have to play in separate leagues and shouldn’t be allowed to play with the boys. There are coed teams right now. It may not have the label of ‘coed,’ but I am playing on a coed baseball team.”

Rivera also sees the positives in allowing girls to continue to compete alongside and against boys.

“It’s fun to see the reaction on the guys’ faces when a girl strikes them out,” Rivera says. “A lot of guys see girls as being weaker, but when they get struck out by a girl it has to change their opinion.”

Gauci is also used to playing with boys but believes that there should be more opportunities for girls and women to play together.

“In Australia, it’s not strange at all to have two or three girls on a baseball team,” she says. “But with coed teams, only a select few will be given the right developmental opportunities to play. If we had all-girls teams, it would open up the doors for a lot more girls to play and train.”

The doors will edge open a bit more next year, as the ranks of women playing college baseball continue to grow. Alexia Jorge, a catcher for the varsity team at Lyndhurst (N.J.) High School, has committed to play at Saint Elizabeth University, a D-III program. Righthander Alli Schroder has signed with Vancouver Island University, making her the first woman to suit up for a Canadian College Baseball Conference team.

“The more girls who play the more acceptable it will become in the eyes of society,” Gauci says. “I don’t think it will ever be viewed as completely normal, but as more women play the more normal it will become. It’s not going to be an overnight thing; it will definitely be a gradual change.”

Even if it’s incremental, it’s progress nonetheless. And the more women who play baseball at the college level, the more barriers will fall—and the more girls will feel like they belong in the sport.

“It’s easier to be something if you can see it,” Greenwood says. “Little girls see that there are women who are playing high school and college baseball and may think, ‘Wow, this is something I want to do and it is something I can be.’ The growth I have seen over the last 10 years has been crazy. I definitely think things are heading in the right direction.”

Michael Rosen is a contributor for GoodSport, a media company dedicated to raising the visibility of women and girls in sports.

More Baseball Coverage:

• Scherzer-Girardi Fiasco Reveals Worst of Sticky Stuff Crackdown

• Jacob deGrom's Dominance Is Beyond Comprehension

• For Ohtani and Others, an Interpreter Is So Much More Than You Think

• Tragedy and Hope: A Prospect, a Scout and a Pop Fly