You don't know Muhammad Ali until you know his best friend

This story originally appeared in the July 13, 1998 issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

Outside, the house is neat and trim, not unlike the owner himself, who possesses one of those perfectly oval faces—bald on top, bearded on the bottom—that, in caricature class, could be turned upside down and drawn just as well that way. The eyebrows are small, the eyes aglimmer, and the mouth is invariably found in a smile, perhaps because, for so long, it wasn’t much good at dispensing words.

Nature compensates.

But some things are distinct and immutable, such as the accepted fact that this fellow with the oval face is the nicest person in sports (which might be damning him with faint praise) and may be the nicest person on the face of the earth.

Best Person Around, for $200.

Who is Howard Bingham?

We do know this: The one person—and he is a famous person—who mistreated Mr. Bingham hasn’t amounted to a hill of beans since then.

There is a God.

From The Vault: Every Ali Cover Story

- Cassius invades Britain

- My $1,000,000 Getaway

- Cassius—His Fight And His Future

- The Big Fight: Can Clay Do It Again?

- Cassius Clay vs. Sonny Liston

- The Fight You Didn't See

- The Big Fight: Clay vs. Patterson

- Cassius Clay: The Man, the Muslim, the Mystery

- The Big Fight: Clay vs. Terrell

- Scramble for Ali's title

- Ali-Clay; the once and future king?

- The Slugger And The Boxer

- End of the Ali legend

- The future is a mist

- The Jaw is broken

- Ali Again

- Muhammad Ali: Sportsman of the Year

- Boxing's New Barnum

- The Epic Battle

- Ali's Road Show Rolls On

- Ali's Desperate Hour

- The Champ Again

- Look Who's Back!

- He's no Liston. He's no Frazier.

- The Last Hurrah

- The man and his entourage today

- 35th anniversary

- Once and Forever

- Battle of Champions: Ali vs. Frazier

- Who's that guy with Howard Bingham?

And now, driving up to his neat and trim abode, here comes Howard Bingham in his old Camry, one drab and indistinct of color and loaded with even more junk than miles, which total 108,000. Howard’s dog, Clyde, stirs. Clyde is part rottweiler, part German shepherd, but, as befits the dog of such a sweet guy, Clyde prefers the learned life of lying about to the vigilant one for which he was bred.

Howard calls out to one of his neighbors. The women in these environs of south Los Angeles all look after Howard, feeding Clyde when Howard is traveling or feeding Howard when he is home. He’s away a lot, though, consorting with the rich and famous here and there, everywhere. Still, he has lived in this little house since 1969. It is not far from the house he grew up in, where his mother still resides. He uses that residence as a mail drop, sparing the helpful neighbor women postal chores too.

Howard opens his front door. “People don’t believe it, that I still live here,” he says. “But I’m not fancy. You can only sleep on one bed.”

Well, you can if there isn't stuff piled on it. Howard's house, the stationary version of Howard's car, is something of a cross between a flea market and a mail-order warehouse. Friends like to say that Howard has “a file cabinet in his head.” This house is the wrong place for a file cabinet. Stuff is piled about, sometimes nearly to the ceiling—the accumulated effluvia of The American Man Alone.

One room passes for the eye of the hurricane. This is where Howard stockpiles hundreds of thousands of his negatives. He is, by trade, a photographer, and a very good one. For the celebrity gentry he is the anti-paparazzo, the photographer as gentleman.

Across from the Bingham archives is another room, fashioned as command central. One of Howard's friends, Mary Williams, a public relations woman, says that he’s on the phone so much that he reminds her foremost of Ernestine, Lily Tomlin’s telephone operator. Howard works not only the phones but also the fax and the E-mail while cuing up the TV and the VCR. Also his wont is to patch people together—people who share nothing in common but Howard Bingham. Suddenly you are not just schmoozing with Howard. You are on a three-way hookup with someone you never heard of in Asuncion, Paraguay. “Hello,” says Howard, talking on the phone to some big shot's secretary. “It’s your favorite person.”

“Oh, it must be Howard Bingham,” the secretary replies.

But now, brushing his chair free of bric-a-brac, making a small place for his own self, Bingham has a single call to make to just one person. He speed dials. He says,“Hi, Bill.”

The voice on the other end, barely audible, replies,“Hi, Bill.”

The murmur belongs to Muhammad Ali. He and Howard Bingham are the best of pals, the Damon and Pythias of our time. They have loved each other for 35 1/2 years, through thick and thin, championships and marriages and children; through their lives, across our time.

So, a few days later, in another place, Ali smiles, looking across the room to Bingham, and behind the trembling hands and the flaccid face, there is a glint in his eyes that suddenly shines from a time when the world lay at his feet and he was as healthy and as handsome as God ever made one man. But never mind that. It's O.K.“I'm lucky,” Ali mumbles. “Did you ever have a good friend?”

If not so tenderly, but somewhat more poetically, Emerson said,“A friend may well be reckoned the masterpiece of nature.” What is distinctive about Bingham is not only that he has been in Ali’s corner all this time—good god, he even went along on one of Ali's honeymoons ... at the invitation of the bride—but also that he is no less the dear friend of so many others. In this mean gotcha world, listening to people go on about how nice Bingham is gets downright saccharine. A cross section: George Jackson, president of Motown Records: “When you look up the word benevolent in the dictionary, it should have Howard’s picture next to it.”

Gordon Parks, photographer: “Just a jewel of a guy.” (Parks doesn't keep a photo of Ali on his wall; he keeps one of Ali and Bingham together.)

John Jay Hooker, former chairman of STP Corp., now running for the Democratic nomination for governor of Tennessee, “Some people kid Howard that he's a professional guest. But Howard is entitled because of how he acts. He’s traveling this earth on a special passport. You know, if I learned I was going to die, I couldn't think of anything I'd rather do than spend some time with Howard Bingham.”

And just as Bingham is loved by everybody who knows him, so does he somehow end up everywhere. “You know,” he sighs, guilelessly, “I’m in history.”

George Fisher, chairman of Kodak, says in amazement,“Sometimes I think there must be 10 of Howard. It’s like he's everywhere.”

Before Forrest Gump and before Zelig, there was an old gag about a little guy named Sam who was ubiquitous. The joke ends at St. Peter’s Square on Easter morning as somebody in the crowd says,“I don't know who the old man in the beanie is up on the balcony, but the guy with him is Sam.” Thus: Howard. It surprised no one, really, that when O.J. Simpson left L.A. for Chicago in the middle of the night after practicing golf shots in the dark, Bingham was on that flight. And, naturally, at Simpson’s trial, it was concluded that Bingham was the only witness both sides liked.

Johnnie Cochran, approaching the witness: “Are you a world-renowned photographer?”

Bingham: “The world's greatest.”

Cochran: “So, we’re clear about that.”

Later, on cross-examination, when Marcia Clark made a passing reference to Bingham as an outstanding photographer, Judge Lance Ito interrupted: “Uh, the world’s greatest.”

Bingham: “You’re a smart man, judge.”

For the faceless nobody who was so long dismissed as just another sycophant in the Champ’s entourage—the one who stuttered; don’t even bother with him—the ease and confidence and humor that Bingham now displays is the stuff of metamorphosis. But then, Bingham has met presidents and dictators and a huge segment of the population with Q ratings. Plus all the right maitre d's. Would it surprise you to learn that Bingham interviewed James Earl Ray? (“Howard completely charmed him,” reports someone who observed the tete-a-tete between the black man and the racist.) He's met and photographed Elvis, the Beatles and Michael Jackson. James Earl Jones lent his grand voice to a Black History Month radio feature on Bingham. Here is a picture of Bingham with President Clinton, Billy Graham and Lauren Bacall. Here is another, with Bill Cosby and Nelson Mandela. Howard is the one in the middle. On the Internet, Bingham is on the select list of history's most famous stutterers, which includes Demosthenes. Surely it won't be long before someone says, “I don’t know who the big fellow is up there shaking, but the bald guy with him is Howard.”

He is amazingly eclectic. He befriends strangers on elevators. On this particular morning he hands over the Camry to the valet parking attendant at The Beverly Hills Hotel and strides inside, where Arianna Huffington and a bunch of Hollywood muckety-mucks have come to a breakfast to hear Orrin Hatch, the conservative Republican senator from Utah, deliver a speech. The Beverly Hills looks, in fact, a lot like Utah, lacking any black people.

Except Howard Bingham.

Hatch enters the room. All the fat cats start to move toward him. Suddenly, the distinguished senior senator stops dead in his tracks. He falls into a boxer’s crouch. It looks as if Hatch, usually so impeccable, so controlled, has lost it. But no, he has just spied Bingham across the way. The two men once met. They became friends. That's the way it goes with Bingham. Now, while everybody else looks on in puzzlement, the senator hurries to the one black man in the room and, beaming, embraces him. There is more hugging by and of Howard Bingham than goes on in a whole stadium of Promise Keepers.

At the microphone Hatch tries to rag on Bingham a little bit for being the lone Democrat in this Republican crowd. But the senator knows it's futile. Ali couldn't get Bingham to convert to Islam all those years when virtually all the other African-Americans surrounding the Champ were Muslims. So what chance does Hatch have? Ali must see some of himself in Bingham. It wasn't Ali’s boxing talent that made him so special; rather, it was that he stood up for his beliefs. Well, it isn't just Bingham's niceness that makes him so special; rather, it is that he stands up for his beliefs.

“That’s hard, too,” says Lonnie Ali, the fighter's fourth wife.” To say to a personality as powerful and overwhelming as Muhammad—to say, ‘No, you’re wrong. I don't agree with you!’—that's very difficult. But Howard was never a yes-man. He always tells Muhammad what he feels he has to know.”

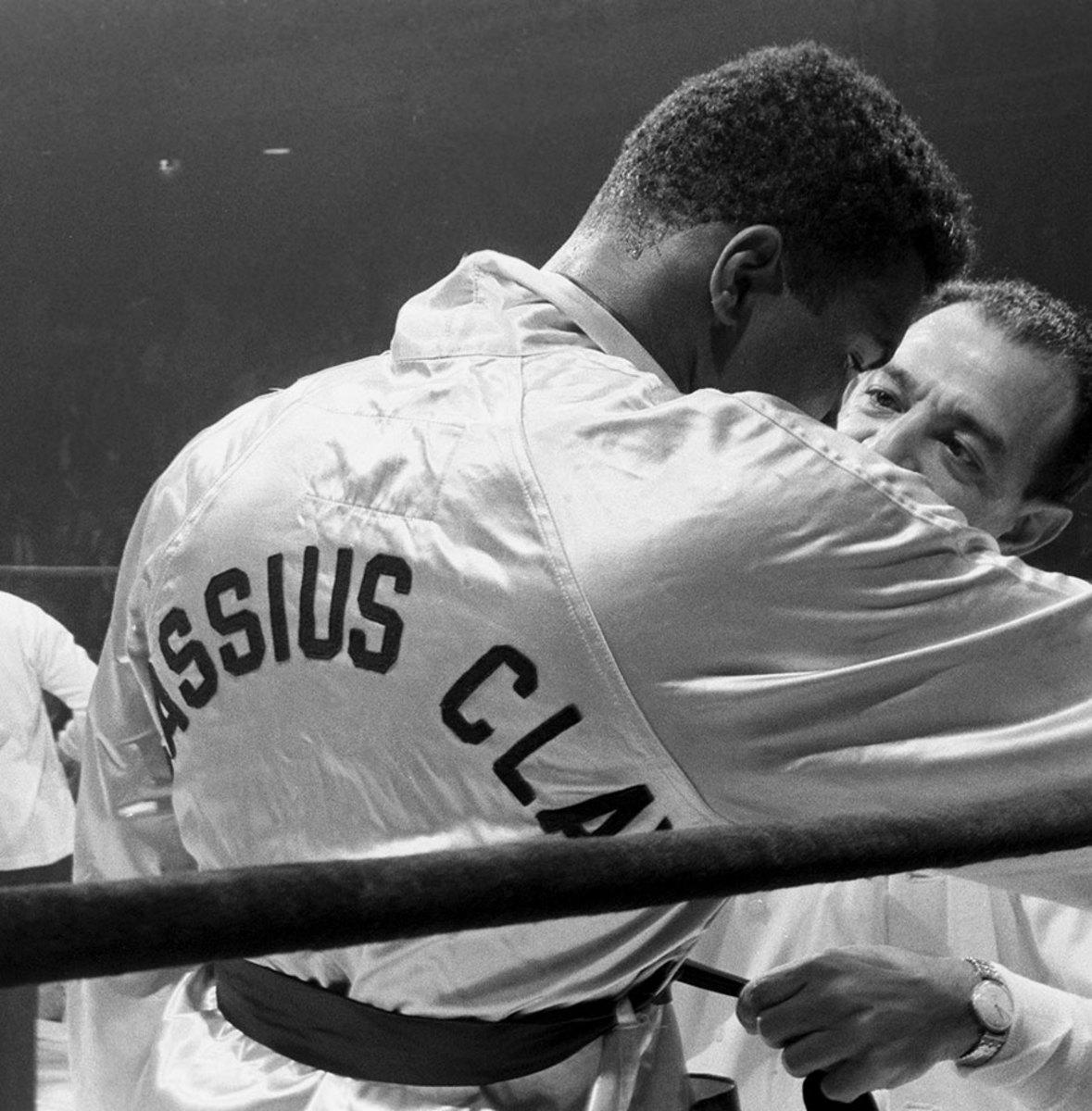

Did you ever have a good friend? Bingham steers the Camry to downtown L.A., first to a good taco stand and then to the corner of Fifth and Broadway. This is the historical part of the tour, the one that revisits the moment of happenstance that changed Bingham's life. Late in 1962 one Cassius Clay and his brother, Rudolph Valentino Clay, were standing on this corner, watching the girls go by. Howard came along in his Dodge Dart. He was learning to be a photographer at the Sentinel, L.A.’s black weekly paper. It seemed quixotic.

He’d taken up the craft mostly because, for a guy who couldn’t talk, it seemed like a good way to meet chicks. So far he’d gotten an ‘F’ in photography at Compton Community College and overexposed most of what he shot for the Sentinel. Still, the paper had sent him that day to a press conference to shoot the loudmouth young heavyweight who was in town to knock over some tomato can.

The Clay brothers got into the Dodge Dart, and Howard gave them a sophisticated tour. Besides looking for girls, he took them to a bowling alley and home to meet his mother. Later, his chauffeuring had more of a purpose to it. “Remember, Ali,” Howard now says to his friend,“I’d drop you off at the mosque—making sure there were no white folks around to see.”

Ali laughs at the recollection of being a closet Muslim, surreptitiously driven about by the Christian preacher's son. Otherwise, for more secular pursuits, Bingham and his new buddy started to hang out. “We just got along,” Howard says. It was all fun. They were free, black and 21. Shortly after Ali returned East, he sent Bingham a ticket, and Bingham took his first plane ride, to Miami. There he and Ali picked up the fighter’s pink Cadillac and drove north, to Louisville. It was wintertime. Bingham had been born in Mississippi and had grown up in L.A. and didn’t have any cold-weather clothes. Ali outfitted him, and Bingham decided to stay. It was like suddenly being taken into Wonderland.

“I’d never even heard of you, Ali,” Bingham says now. “Shows how dumb you were.”

“I wish I’d kept a diary,” Bingham says. “I wish I’d known you were going to become the Muhammad Ali the whole world knew.”

But he did take pictures, and he got better at it. Before long the country started to rip apart at its racial seams, but then (as now) there weren’t many black news photographers, and Bingham got his chance. After all, everybody liked him, and everybody trusted him. For LIFE, the Black Panthers let Bingham photograph their huge weapons cache, secure that he would not reveal where he had shot the arsenal. But always Bingham would return to Ali, to be with him and photograph him. “I love to go places with him,” he says, even now, in his 60th year. “I get so mad sometimes when I have to do something and I can't go with him.”

The stacks of pictures began to pile up. Ten thousand, a hundred thousand, another hundred thousand. By now Bingham may have shot a half-million photos of Ali. Who knows? How many more snapshots has Bingham taken for people who spot Ali, jam their Instamatics into Bingham's hands and plead with him to take a picture of them with the Greatest? Muhammad Ali probably has had his picture taken more times than anyone in the history of the world—and probably had his picture taken by more people.

Now, though, his body slumps and his hands tremble and his eyes close, and Howard and Lonnie try to stir him. “Open your eyes, Ali,” Howard snaps.

They are in a fancy studio in Manhattan. The fashion photographer Francesco Scavullo is taking Ali’s picture for a restaurant advertisement. “Lonnie, his left eye is drooping,” Howard calls out.

Lonnie says, “Ali, Halle Berry is here.”

Don’t they wish. Children and good-looking women open Ali’s eyes. Luckily, two pretty young women, if not Halle Berry, arrive. The women are from IMG, which represents Ali. He will never be one of those stumblebum boxers scuffling for walking-around money. Poor Joe Louis was called America’s Guest. Muhammad Ali is America’s Honored Guest. Now that it is the end of the century, he is remembered all the more as we tote up the best recollections of the 1900s. Muhammad Ali! The greatest this! The finest that! Accept this honor! Take this award! And he loves it. But, of course, all the accolades, all the adulation, all the photo shoots don't stop him from shaking or from falling asleep. Open your eyes, Ali!

Ali spots one of the women, IMG attorney Catherine Lindsey, hugging Howard. “The famous Howard Bingham,” Catherine coos.

Catherine happens to be blonde. Lonnie says,“Good. Muhammad likes blondes.”

Howard hugs the other woman, Catherine's assistant, Sheila Willis, before he can be introduced. Ali takes note of this, too. His eyes don't droop anymore as he follows the track of Catherine. “He’s flirting and doesn't think I can see,” Lonnie says.

“Flashbacks, Lonnie,” Howard sighs. “It’s only flashbacks.” She smiles; Lonnie knew Ali long before he married her, when he was a notorious skirt chaser. Now he’s just a looker and a flirter. A few minutes later, after Scavullo is through shooting, Ali sneaks up behind Sheila and tries to flick her ear. But she turns her head at just that instant, and he isn't agile enough to touch her. Sheila never even knows what happened.

Bingham doesn't see this. But not two minutes later, he sneaks up behind Sheila and tries the exact same thing. Only he succeeds at yanking her hair, so she whirls about in surprise. “Pranksters,” Lonnie says, sighing. Sometimes it's hard to see where Ali stops and Bingham begins. Bingham is 59 and has two grown children, and Ali is 56 and has eight grown children, but more often than not Lonnie, who is 15 years her husband’s junior, seems to be the only grownup on the premises, Wendy to the Lost Boys.

Now it’s true that Lonnie sometimes goes into cahoots with Howard. To all Ali’s previous wives, Bingham could say—would say—“I was here before you, and I’ll be here after you’re gone.” But Lonnie is different, and, like Howard, she isn’t going anywhere. She was literally the little girl next door; she met Ali when she was only six years old. Now the two silly men-boys sometimes drag her down to their level. Their favorite skit, the three of them together, works best when the mark is a reporter who is earnestly interviewing Ali while Lonnie or Howard interprets his murmurings. Invariably the reporter is very solicitous, very moved that the Greatest is now nothing but this trembling shadow of what he was. Ali nods off, and the game is under way. This time, you see, Ali is pretending. Lonnie and Howard play their parts. Sharply Howard barks, “Lonnie, don’t let him do that. Wake him up!"

She snaps back, “The doctor said to let him go when he does this.” The reporter, mournful, tries to remain composed amid this sadness. Ali, eyes still closed, starts to throw little jabs.

Sorrowfully, Lonnie explains,“His mind is playing tricks on him. He thinks he's back in the ring, fighting again.” Howard nods in melancholy.

Then—pow! Without warning, Ali throws a monstrous jab that just misses the unsuspecting man's chin. Ali’s eyes are open wide now, and he chortles. Lonnie and Howard grin to beat the band.

A lot of life with Ali is Kabuki theater, the same polished routines over and over. He levitates off his feet, performs the disappearing handkerchief trick, scowls when Bingham introduces him as Joe Frazier, repeats the same few timeless gags. “Ali wants to tell you the Abraham Lincoln joke,” Bingham says.

You draw closer. Ali says, “You know what Abraham Lincoln said after he came off a two-day drunk?”

No, Muhammad, what did Abraham Lincoln say after he came off a two-day drunk?

“I freed the whaaaat?” He laughs at his favorite punch line as heartily as if it were the first time he’s heard it.

It is not that his mind is diminished by the Parkinson's or that he is some old pug on Queer Street. Rather, it seems as if Ali voluntarily closed down the progress of his mind when the disease inhabited his body. Now he works only at growing sweeter. More and more he is like a soul walking. But the past is all still there, ready to be called back. Why, he can even, for a few seconds, perform the Ali Shuffle, tossing punches rat-a-tat-tat while his feet scamper back and forth. That is the best magic trick of all. But then he is winded, and he collapses, and, in mock admiration, Howard pats his potbelly.

Another time, in the Presidential Suite of a hotel where the Alis are staying, Ali sits on the bench of a grand piano and plays a very serviceable rendition of ... yes, The Tennessee Waltz. Where did that come from? Howard sits by him and plays Heart and Soul. How many times have they done that? For how many years?

Now the two old friends sit together again, watching the video of a new documentary that Bingham has brought over. It is called City at Peace, and it is about black and white kids trying to get along. When one of the girls in the video laments that whites go in one car and blacks in another, Ali nods knowingly. “Nature’s way,” he says, “nature’s way.”

Bingham tries to dispute this, pointing out that the whole thrust of the documentary is that the races can get along better if only they know each other better. But Ali is having none of that—and never mind that he lives his life race-blind. Bingham shrugs. It’s the old Black Muslim philosophy. “I don’t argue with him on religion,” Howard says. “What’s the point of that?”

Like the jokes and the magic tricks, though, Ali still brings up the same standard arguments. Thirty-five years and counting, and he is still bugging Howard about his “slave name.” Bingham tunes out as Ali begins again, “Germans have German names, and Puerto Ricans have Puerto Rican names, and Indians have Indian names, and you can tell who they are, but if your name is Johnson or Jefferson or Bingham, you don’t know who that is till you see him.”

Bingham doesn't bite. But sometimes, when Ali starts in with a newcomer, pointing out the various contradictions in the Bible, Bingham pleads with him, “Ali, why don't you stop talking against Christianity and the Bible? Why don't you just get up a pamphlet that has your picture on it and tells all the good things that Islam has done for you? Now, people would like that.”

Ali ignores that suggestion, as he always has. So, he and Bingham enjoy some fruit and some crackers together, watching the documentary. Soon, though, Ali starts to nod. For real. His eyes close, his head falls to his chest. Bingham turns to glance at him. He and Lonnie do not treat the old Champ with any pity, or really with much sympathy. It angers Bingham that Ali doesn't work out hard enough. He tells Ali so—to no effect. “Ali’s lazy,” Bingham says. “He’s overweight, but he's convinced himself that he can lose weight only in Miami, because that's where he went to lose weight when he was boxing. He just won’t work at it.” The past is the only present left.

There is this irony, too: Bingham was never any sort of athlete. He could never identify with his friend. But he sees that Ali has grown more like him. Their impairments are different, of course, but the point is the same: You owe it to yourself to deal with whatever infirmity you have. Once, Bingham could hardly speak, his stutter was so bad. He found out that his impediment probably came from trying too hard never to offend anybody. He held everything in. He was the oldest of seven children—too good, too dutiful, always dependable, never a problem.

Once Bingham understood better why he stuttered, he could work at correcting the problem. “See—look,” he says, and, driving along in the Camry, he suddenly unleashes a stream of vulgarities. Then he smiles. “See? I let it out.” It was like a time years ago when he was in a car being driven by Belinda, Ali’s second wife. She turned in front of a truck, and Bingham screamed, “Look out!”

After they'd escaped danger, Belinda said, “Why, Howard, you didn't stutter.”

“I di-d-di-didn't h-h-have t-t-time t-t-to.”

In fact, everybody pretty much accepted Bingham’s stammer. “No one even perceived it as a handicap,” George Jackson says. “It was just another part of Howard.” Another notation on his special passport.

But, of course, it bothered him. In 1978, to everyone's surprise, he ran for Congress in his home district. He had a lot of support—Marvin Gaye, Sammy Davis Jr., Richard Pryor, the works. Ali campaigned, too, and he wrote a poem: Bingham is smart

Bingham is wise

Elect Howard Bingham

Cut our problems down to size.

Unfortunately, at candidates’ forums, Bingham would seize up as his turn to speak approached. He would run from the stage before the microphone was his. He lost the election.

But even if he never ran for office again, he never stopped trying to speak better. Now he knows: Muhammad Ali may have been the Greatest, but Howard Bingham dealt better with his infirmity. Sometimes, he tells his friend, “It isn’t your fault, Ali, that you're only 50 or 75 percent of what you were, but still, if you won't give 100 percent of what’s left, then you might as well keep your ass at home.”

But at other times he looks at his friend, and he remembers only the beauty—that wonderful, powerful body, that dashing, fascinating original that was. “Oh, yeah,” Howard says, “sometimes when I remember, it hurts.”

He looks over at Ali on the couch, chubby and droopy, dozing off again. Softly, Howard reaches out and touches Muhammad—just enough, on the side of the head, to awaken him. Just enough. Ali stirs. He looks up torpidly, sees his friend and smiles.

The documentary is still playing. Lonnie is on the phone at the desk, talking business. Without a word, Ali lowers his head and goes back to sleep.

Bingham looks after him. It is all right. He feels a sadness for what was, but a joy for what remains.

Recently, when Bingham was named Photographer of the Year by the Photographic Marketing Distribution Association, he put together a collection of his best work. George Fisher of Kodak says, “You see his pictures, you know he relates to his subjects in a special way.” Bingham included a couple of photos that were precious to him. They were of Ennis Cosby, who had been murdered a few months earlier at age 27. Bingham dedicated the award to him.

The Cosbys have always been important to Bingham. Bill fractured the tacit color line in the still cameramen's union by bringing Bingham onto the set of his TV show in 1969—even though it meant also paying a white union shooter just to sit there. Over the years Bingham, who is divorced, has also grown close to Camille Cosby, who refers to the “special bond” she shares with him. Rarely does a day go by without their speaking to each other.

Despite their age difference, Bingham felt a particularly strong connection to Ennis. Camille and Bill are almost effortlessly accomplished; Ennis, though, had to deal with dyslexia, just as Howard had to contend with his stutter. When the young man was murdered, the Cosbys turned to Bingham to handle the arrangements concerning the body in Los Angeles and its transportation to western Massachusetts, where Ennis would be buried.

A couple of days later, on a bitter January morning at the Cosby farm, Bingham and a handful of other close friends gathered with the family. At the grave they stood in a circle and held hands while each, in turn, gave a eulogy. When it was Howard’s time, he told of the Sunday he had taken Ennis to a Dolphins game in Miami, where he got the young man down on the sidelines. Later Ennis told him, “You know, Mr. Bingham, I like going to a game with you better than going with my father because you can get me down on the field.”

In the midst of their terrible sorrow, all the Cosbys smiled through their tears. “Howard’s so giving, it’s just unbelievable,” says Richard Lapchick, director of the Center for the Study of Sport in Society. Annually, the CSSS gives out an award for excellence in sports journalism, but only twice has it honored the author of a sports book: Arthur Ashe in 1989 for A Hard Road to Glory, his study of the black American athlete, and Howard Bingham in 1994 for his work Muhammad Ali: A Thirty-Year Journey.

Besides being a superb photographic essay, Bingham's book represented the one time that he tried to cash in on his relationship with Ali. “The amazing thing about Howard,” says Neil Leifer, who took the photos for this article, “is that not only did he never abuse his access to Muhammad, but he helped other photographers gain access.” Ali was delighted to help his old friend publicize the book. So it was agreed that he would go on The Arsenio Hall Show. Today the mere mention of the host's name makes every friend of Bingham's shake his head and mutter a curse. Says Lonnie Ali, “In all the time I’ve known Howard, I’ve seen him upset only twice. First was when his father died. Then, with Arsenio. I know he was trying not to cry. He just couldn’t believe it.”

“It” was this: Shortly after Ali agreed to appear on the show with Bingham to publicize the book, the producers began to request that only Ali appear. It was made clear to them that the only reason Ali was coming on was that Bingham would be there. So, reluctantly, Hall accepted the original agreement, and the two friends went to the theater together and waited in the green room. When Hall began the introduction, they were ushered behind a curtain. The host made a big deal out of welcoming someone very special, went to the curtain and pulled out Ali.

Bingham followed. After about two steps onstage, though, when Bingham was barely visible behind Hall and Ali, the host reached down to his belt buckle and made a discreet clutching gesture. It was a prearranged signal. Instantly, a goon appeared on either side of Howard, and while his face registered shock and incredulity, the men restrained him off-camera. The smugly satisfied Hall stepped forward, basking in the Champ’s presence.

Bingham has never gotten over the slight. He still hauls out the tape and shows it in slow motion: the introduction, the Judas gesture, the abduction ... the deceit. Even now, he is not as angry as he is disbelieving that somebody would do such a thing to him, to anybody. “Myself,” he says, “I can’t stand it if I even make someone uncomfortable.”

Oh, by the way, what ever happened to Arsenio Hall?

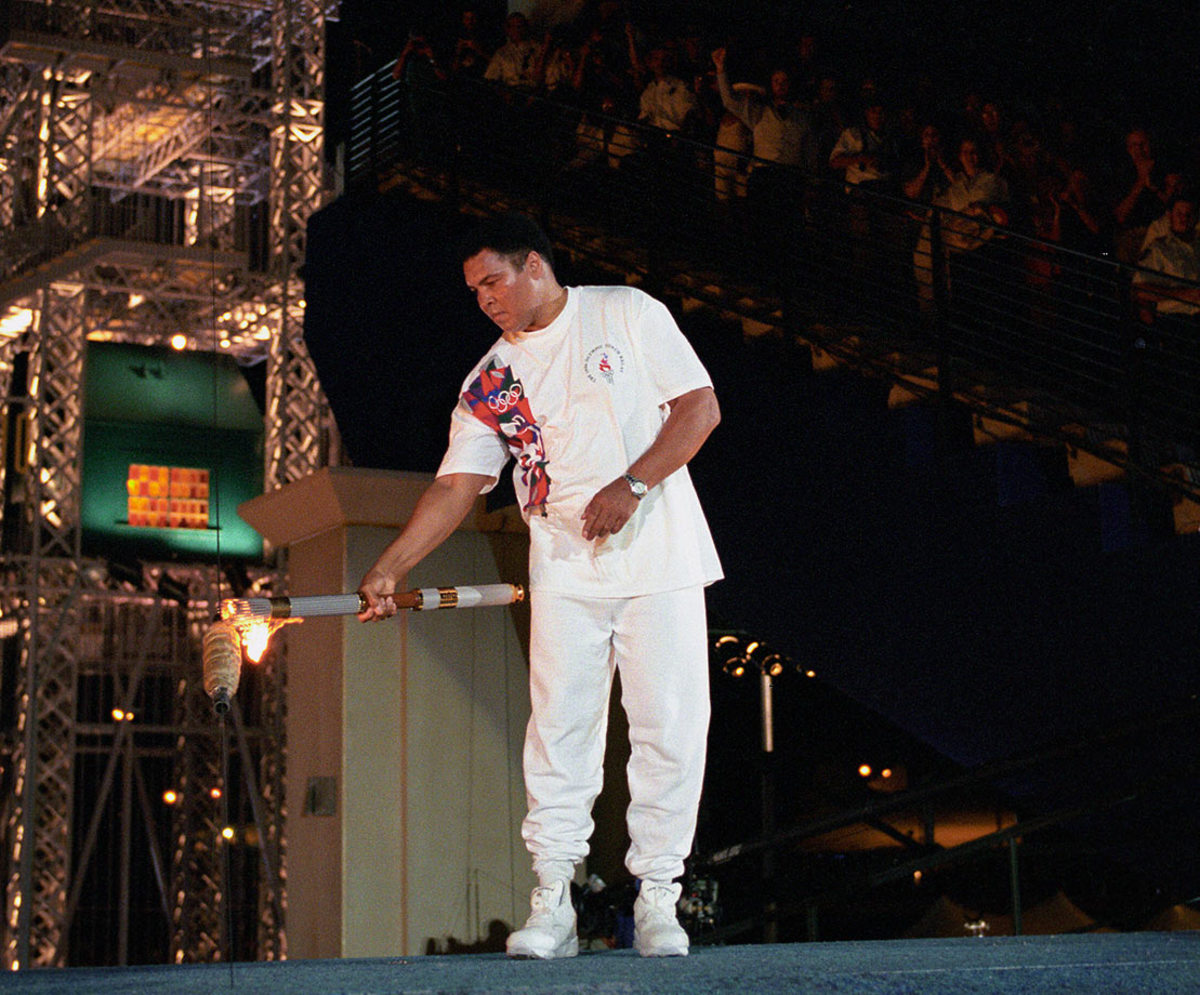

By now, everybody knows that the path to the Champ is through Bingham. He handled all the details when Ali lit the torch at the ‘96 Olympics. Bingham discussed it with Lonnie, of course, but he didn't let Ali know until a few days before the big event. “He can’t keep a secret,” Howard explains.

Besides, Ali didn't appreciate the magnitude of the honor. “He doesn't get excited about anything anymore,” Bingham says. In Tokyo a few years ago, the two of them were together on a high floor of a hotel when an earthquake hit. Bingham cowered, but Ali simply strolled to the window to look down upon the irritated earth. “That's God talking, Bingham” was all he had to offer on the subject. Thomas Hauser, Ali's biographer, says that the only thing that really bothers Ali anymore is his fear that he'll go to a fiery hell for all his sins—carnal division.

Since there is no real time in much of Ali's existence, Bingham is often the travel clock. They have communicated in the same way since the ‘60s: To alert the Champ, Bingham makes a loud clucking noise twice. Time for Ali to move on. Cluck cluck. Sometimes Ali goes cluck cluck in return. Loud and clear. You can hear it even from behind a closed door when Bingham is searching for Ali. Cluck cluck.

“Hi, Bill.”

“Hi, Bill.”

It still confounds Ali that Bingham hasn't done the three things that most of Ali's acquaintances have: beg, borrow and steal from him. “Thirty-five years, never asked for a thing,” Ali says, shaking his head in wonder. Actually, Bingham, honest to the end, volunteers that recently he has hit the Champ up for some dough. “Why you take some now?” Ali asked.

“Because if I didn’t, you'd just give it to someone else.”

This is probably true. How many millions did Ali give away—or let slip away—without hardly noticing? The only thing Bingham regrets, though, is that when the carnival ended, he couldn't persuade his friend not to fight anymore. Ali wouldn't listen to Bingham's pleas, and he kept returning to the ring.

To this day Bingham remains convinced that Ali was somehow drugged before his fight with Larry Holmes in 1980. “Ali had just come from the Mayo Clinic,” Bingham says. “His eyes were so bright when he got to Vegas, and my thinking is that [the people who could profit if Ali lost] saw he was looking much better than they had anticipated. But he took medication he was given in Vegas, and in the ring he wasn't perspiring, he wasn’t fighting. It doesn't make any sense. You know, all these years, I’m still not a boxing expert. I’m just a Muhammad Ali expert, and....” He shrugs helplessly.

Holmes gave Ali a terrible whipping, and, Bingham and some others believe, it was only after that fight that Ali began to change, to grow diminished. But Ali isn’t interested in Bingham's suspicions, even if that bout might have changed his life. It's over and done with, Allah’s will no less than the earthquake in Tokyo.

Likewise, whenever Ali learned that somebody in his confidence had been ripping him off, he avoided any confrontation. There were even occasions when Bingham revealed to him the hard truth about some hanger-on, some buttonhole salesman who was conning him, and Ali got mad at Bingham for being the messenger.

As in the parable of the Lost Son (Muhammad: see Luke 15:11-32), Bingham has played the dutiful younger son, the one who was always there, always faithful. But no matter how many prodigals left with part of Ali's fortune or how truthfully Bingham warned the Champ about those leeches, Ali's response would be, “What do you know, Howard Bingham, you with your slave name? You’re no Muslim.”

Bingham would accept the slights and stay. “Then,” he says,“when everything I told him turned out to be true, he had to notice. You see, everybody around Ali had a cause, but not the cause they said. The cause wasn't Ali. It wasn't Islam. The cause was them.”

Bernie Yuman, manager of Siegfried and Roy, a man long close to Ali and Bingham, says, “Ali realized that if you’re Howard's friend, then you—not him—are foremost on his agenda.”

Herbert Muhammad, a son of Nation of Islam leader Elijah Muhammad who was designated by his father to be Ali's manager, became Bingham's most prominent bete noire. Herbert would never cut the Christian confidant any slack. Bingham, for example, has an extraordinary ability to recall telephone numbers, and Ali, impressed by this sleight of mind, would swirl his head about in astonishment whenever Bingham would throw up 10 digits. It drove Herbert crazy. Once when Ali voiced his amazement at Bingham's gift, Herbert snapped, “It’s only because he hasn't got anything else to do.”

Bingham’s essential sweetness masks a tougher cookie. He sued Arsenio Hall Communications (the suit was settled for an undisclosed amount), and he punched out a member of Ali’s entourage, Gene Kilroy, who was once characterized by a writer as “a white Red Cap.” It was a one-punch fight. “He cocked back; I cocked faster,” Bingham says. With Herbert Muhammad he had to be more subtle, more conniving, but once he almost pulled off a coup. Bingham persuaded Ali to sign a contract that turned over his management to his and Bingham's friend John Jay Hooker, a white Christian. Hooker eventually burned that signed paper, convinced that the contract would create such a dispute with Herbert Muhammad that it would, in the long run, hurt Ali more than help him.

Where he could, Herbert tried to make a nonperson out of Howard. In Ali's autobiography, censored by the Muslims, Bingham’s name appears only a few times. But Bingham would get some sweet revenge through Hauser’s 1991 biography of Ali—which, though authorized, was remarkably candid.

Hauser, a stranger to Ali’s entourage, understood immediately who Bingham was in the scheme of things. “I remember [approaching] Mike Katz of the New York Daily News—he’s supposed to be such a curmudgeon,” Hauser says. “I introduced myself and told him what I was going to do, and the first thing he said was, ‘You’ll love Howard Bingham.’”

Katz was right. In fact, Hauser dedicated the book to Bingham, and he informed Ali beforehand. Delighted, Ali said, “I’m glad you understand how good Howard is.” Then Hauser sat down to read the manuscript to the Alis and Bingham. He asked Ali to stand up and read the dedication. So the Champ rose and, speaking quite clearly, declared, “For Howard Bingham, there’s no one like him.”

Bingham looked up, stunned. “That’s a joke, right?” he said.

Ali shook his head, showing him the page. Bingham began to cry.

In The Camry, Howard is on his way east from L.A. to Claremont, where he has volunteered to show his pictures and speak to a high school assembly. He is looking forward to the challenge. What a wonderful thing it is to stand up and just ... talk.

The kids take to him too. Time for questions. Hands shoot up. Howard points to a pretty girl. She asks, “Mr. Bingham, are you married?”

“Well ... no.”

“Good. Could I introduce you to my mother?”

Everybody hoots. Howard beams. More and more, he is coming into his own. He was chosen to be a keynote speaker at the National Stuttering Project in Atlanta last month. Piece of cake. Hey, in Japan in April he stood beside Ali in front of 70,000 people in the Tokyo Dome and read Ali's greeting to the crowd. Not a halt, not a missed beat. “You know,” Bingham says with a sly smile, “if I could’ve just spoken before like I wanted to, there'd've been no stopping me.”

He's thinking about starting a restaurant between Beverly Hills and Hollywood. Maybe right over there, on La Cienega. The walls would be filled with his pictures, and he’d greet everybody. The place would be called just Bingham's. “It’s finally coming out how important Howard is,” Hauser says. “And I think Howard likes the attention. But no one begrudges him that.”

“Hey,” says Bingham,“tell Ali you don't think I need him anymore, and see what he says.”

Muhammad, I hear Howard says he doesn't need you anymore.

“You tell him he's full of s---.”

Well, he's won all these awards, and everybody knows him, and people are writing stories about him, and he spoke for you before 70,000 people.

“Wasn’t long ago, he couldn't speak at all.”

It is obvious: Ali is very proud of Bingham. “Their relationship is transcendental, almost metaphysical," Jackson says. “But the evolution of these two men’s lives is really a remarkable story in itself. Now it's Howard moving into the sun, and Ali can't be understood so well, but there is Howard, his great friend, who couldn’t speak well, able to speak for him.”

The misconception people had was that Bingham was just Ali’s friend. But it’s never been only that way. What everybody missed was that Ali was Bingham’s friend. It cuts both ways, friendship. For all the loudmouth stuff, all the doggerel, all the braggadocio, Muhammad Ali needed to be a friend as much as he needed to have one. A lot of the time it was just the two of them, quiet and at peace, driving along, hanging out, as often as not staying at some out-of-the-way place in a black area. Just a couple of guys—one of whom, coincidentally, was the most familiar face on the planet, and the other of whom might well have been the nicest person.

“Hey, Bill.”

“Hey, Bill.”

“You see,” says Bernie Yuman, “that's the sign of the most unqualified faith and love and trust. Bill. Simply calling each other Bill. It means, maybe you're a big-deal Muhammad Ali to the world, but that doesn't mean anything to me. To me, you’re just Bill. And Howard became Bill too, because that was Muhammad saying, O.K., we’re on even ground, so you're Bill too. And names don’t mean anything, do they?”

Only love matters to friends. If you have a friend you truly love, whether you’re Howard or Muhammad, well, then you can be a friend to the world.

Cluck cluck.

Cluck cluck.

SI's 100 Greatest Photos of Muhammad Ali

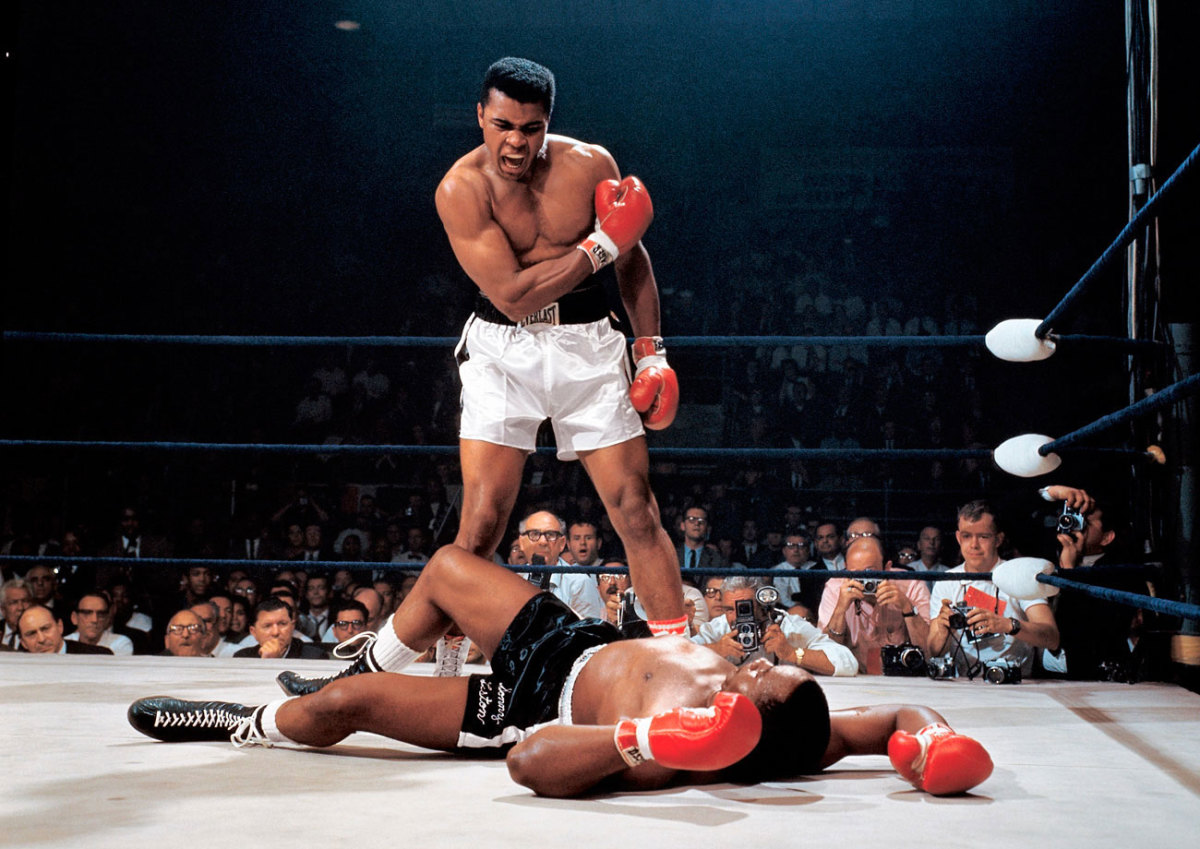

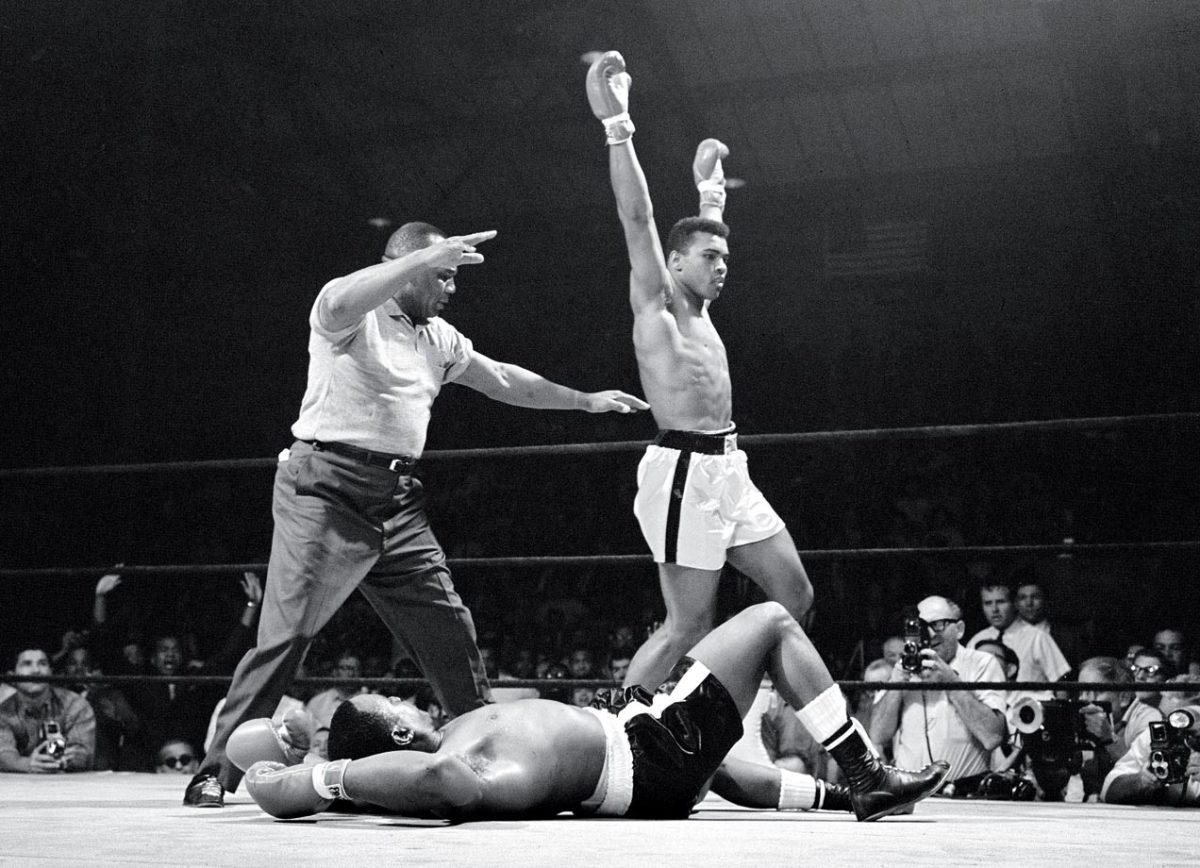

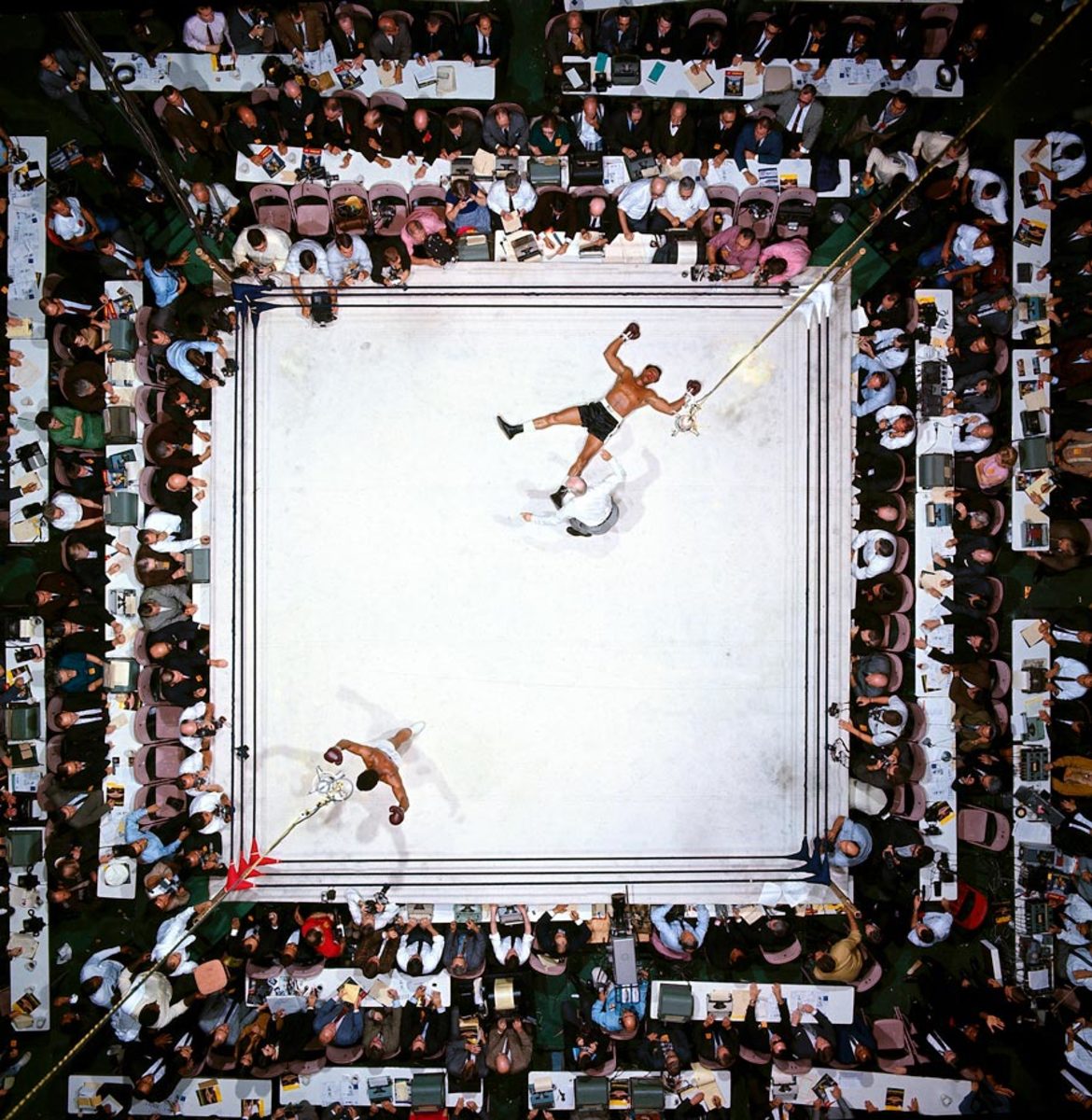

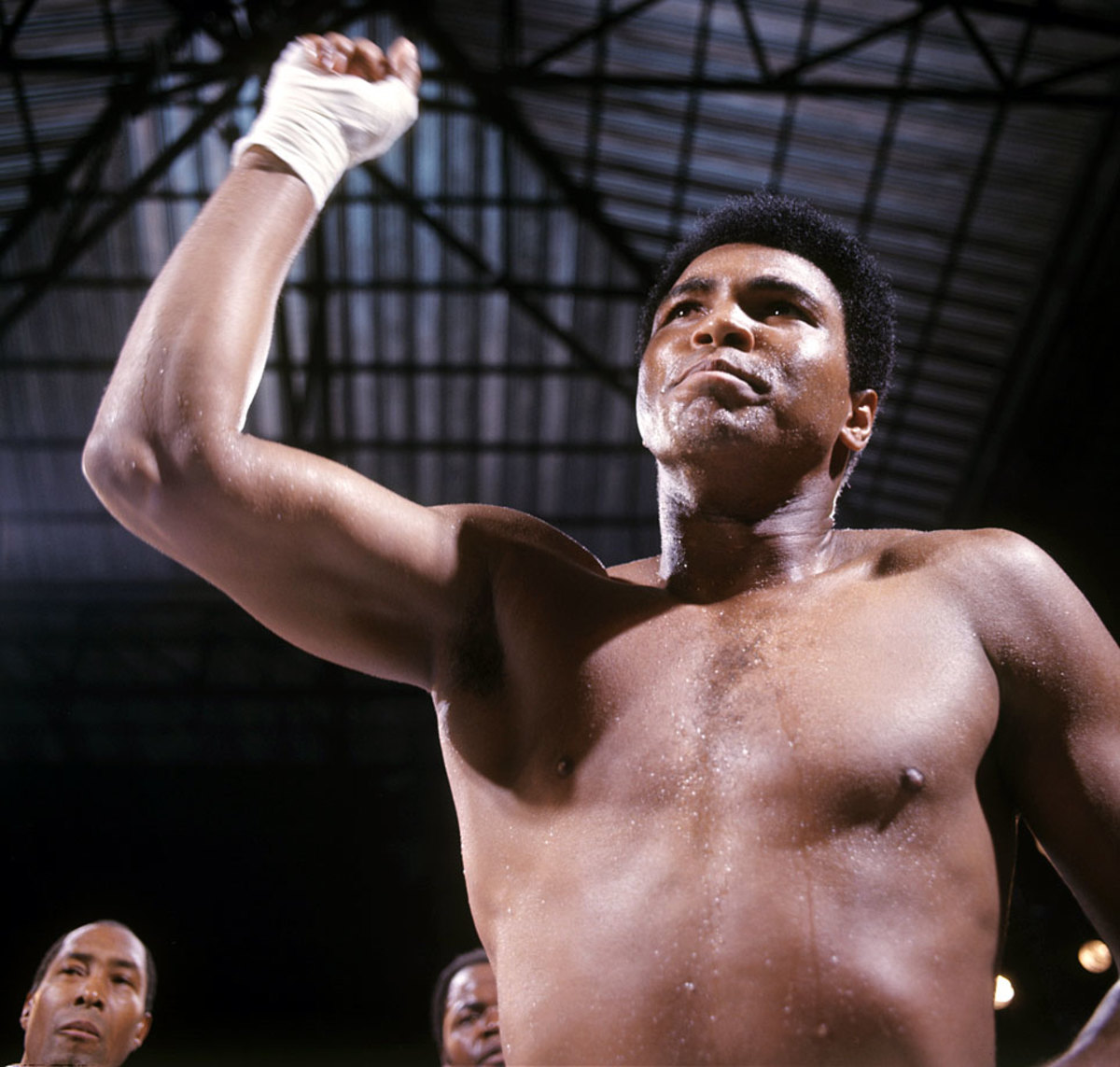

In one of the most iconic and controversial moments of his career, Ali stands over Sonny Liston and yells at him after knocking the former champ down in the first round of their 1965 rematch. Skeptics dubbed it "the Phantom Punch," but films show Ali's flashing right caught Liston flush, knocking him to the canvas. Refusing to go to a neutral corner, Ali stood over Liston and told him to "get up and fight, sucker."

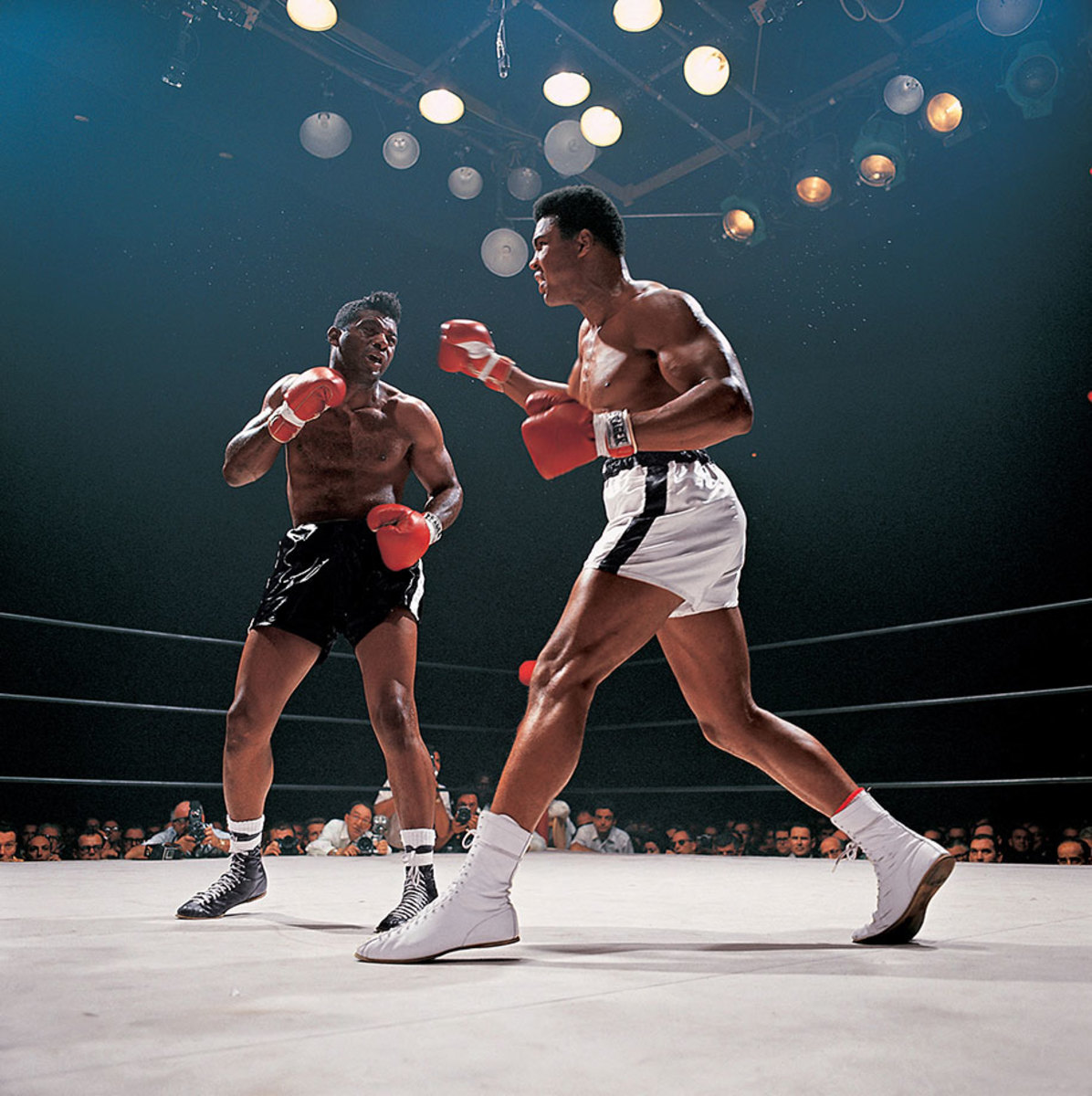

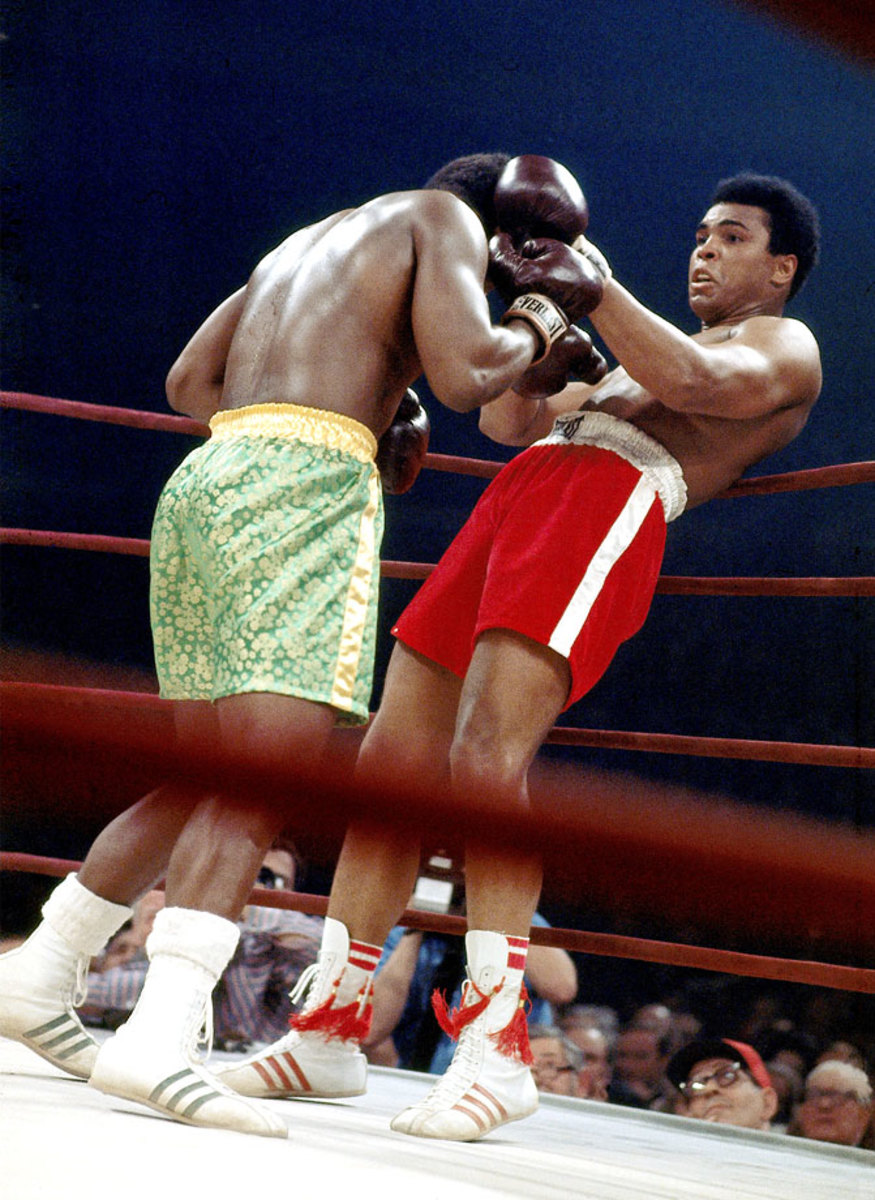

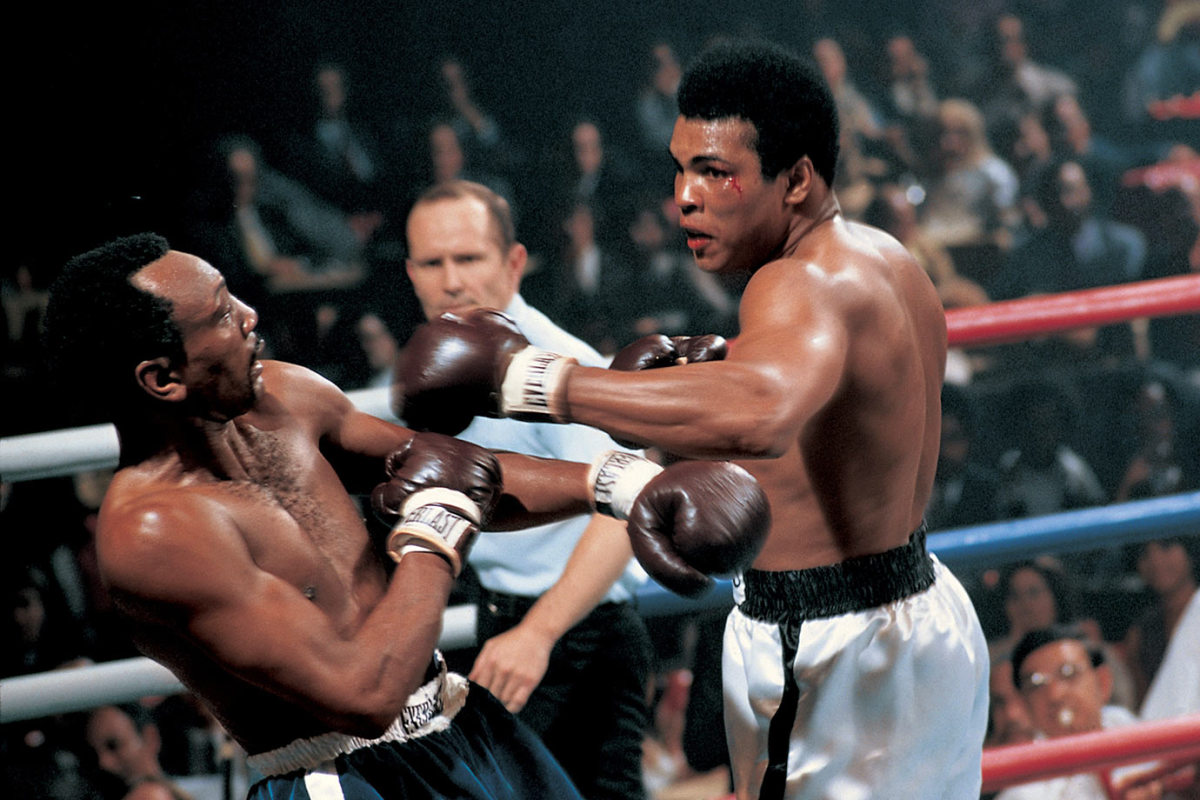

At 22-years-old, Cassius Clay (Muhammad Ali) battered the heavily favored Sonny Liston in a bout that shook the boxing world. The fight ignited the career of one of sports' most charismatic and controversial figures, whose bouts often became social and political events rather than simply sports contests. At the peak of his fame, Muhammad Ali was the best known athlete in the world. Liston, one of the most feared heavyweight champions in history, was a 1-8 favorite over the young challenger known as the Louisville Lip. But Clay, here stinging the champ with a right, used his dazzling speed and constant movement to dominate the action and pile up points.

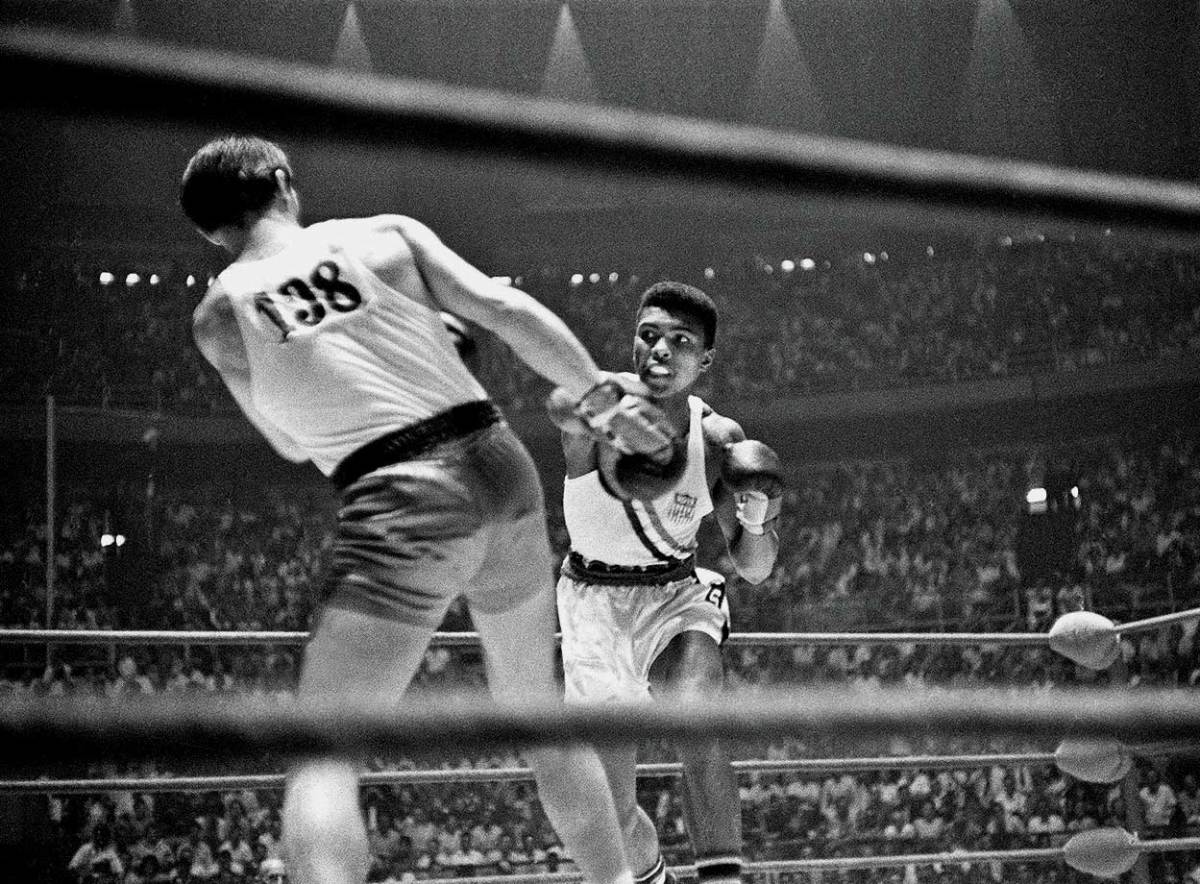

Cassius Clay punches Zbigniew Pietrzykowski of Poland during their gold medal bout at the 1960 Rome Olympics. Clay defeated Pietrzykowski 5-0 for the light heavyweight gold medal.

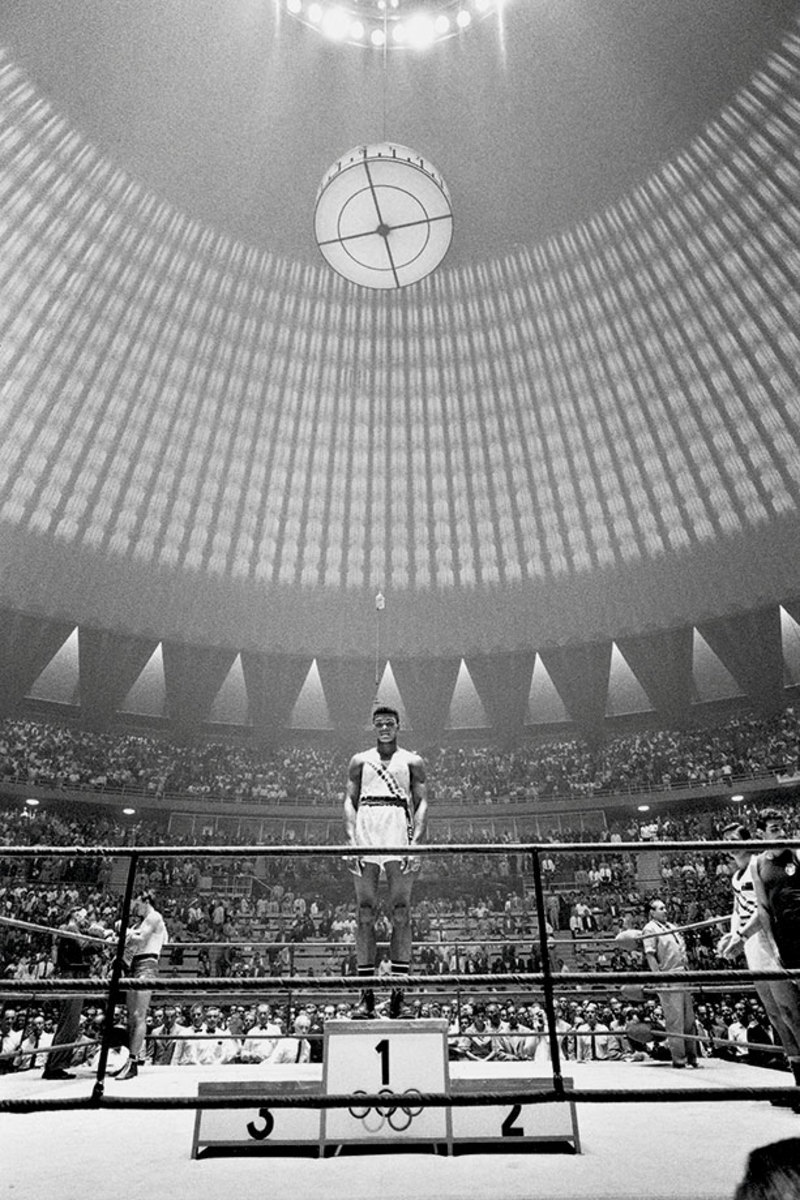

For the 18-year-old from Louisville, here atop the medal stand after his Olympic victory, all roads led from Rome. Clay finished his amateur career with a record of 100-5 and made his professional debut two months after the Games.

Undefeated in his first 17 pro fights, Clay mugged for the camera before the start of his 1963 bout against Doug Jones in Madison Square Garden.

Trainer Angelo Dundee urged his young charge to get serious before the opening bell against Jones. Clay followed instructions and emerged from a tough fight with a unanimous decision victory. Three months later he would stop Henry Cooper and close out 1963 at 19-0.

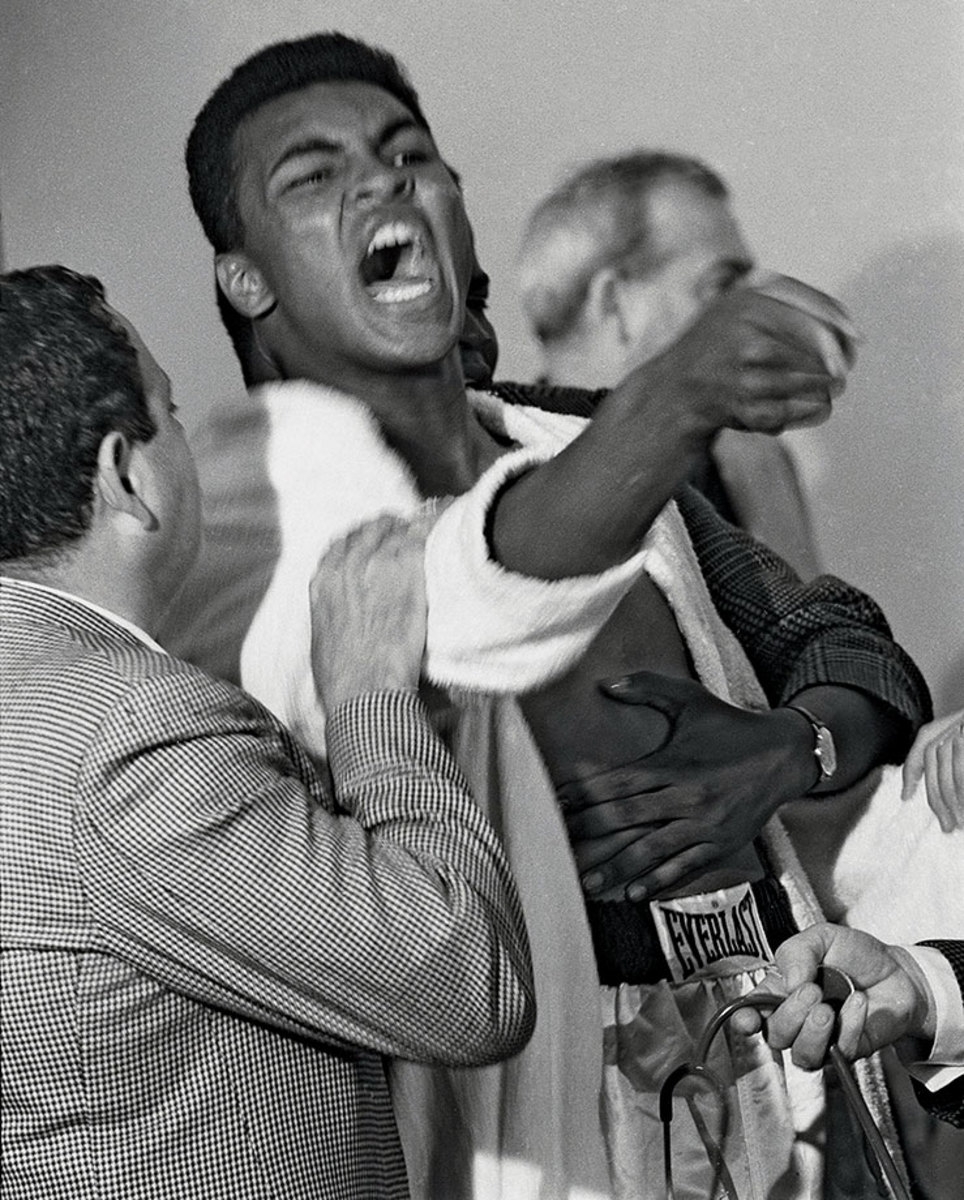

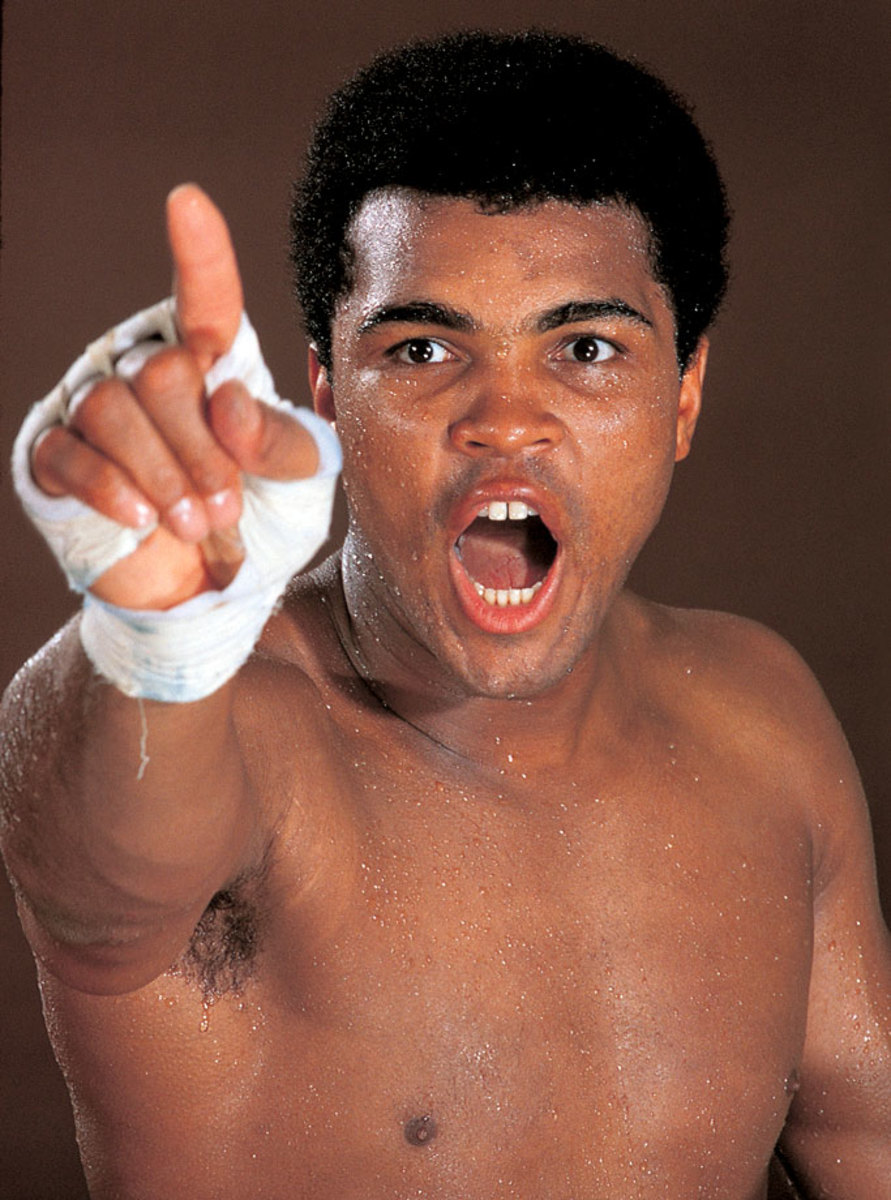

A seemingly hysterical Clay taunted Sonny Liston during the pre-fight physical for their 1964 bout. He had consistently baited the Big Bear during the lead-up to the fight, saying he was going to "use him as a bearskin rug ... after I whup him." The Miami Boxing Commission would fine Clay $2,500 for his outburst at the physical.

"I shook up the world!" an emotional Clay hollered to ringside reporters after his shocking defeat of Liston. And he did just that, claiming the heavyweight title at age 21 after a clearly beaten Liston, complaining of a shoulder injury, failed to answer the bell for the seventh round.

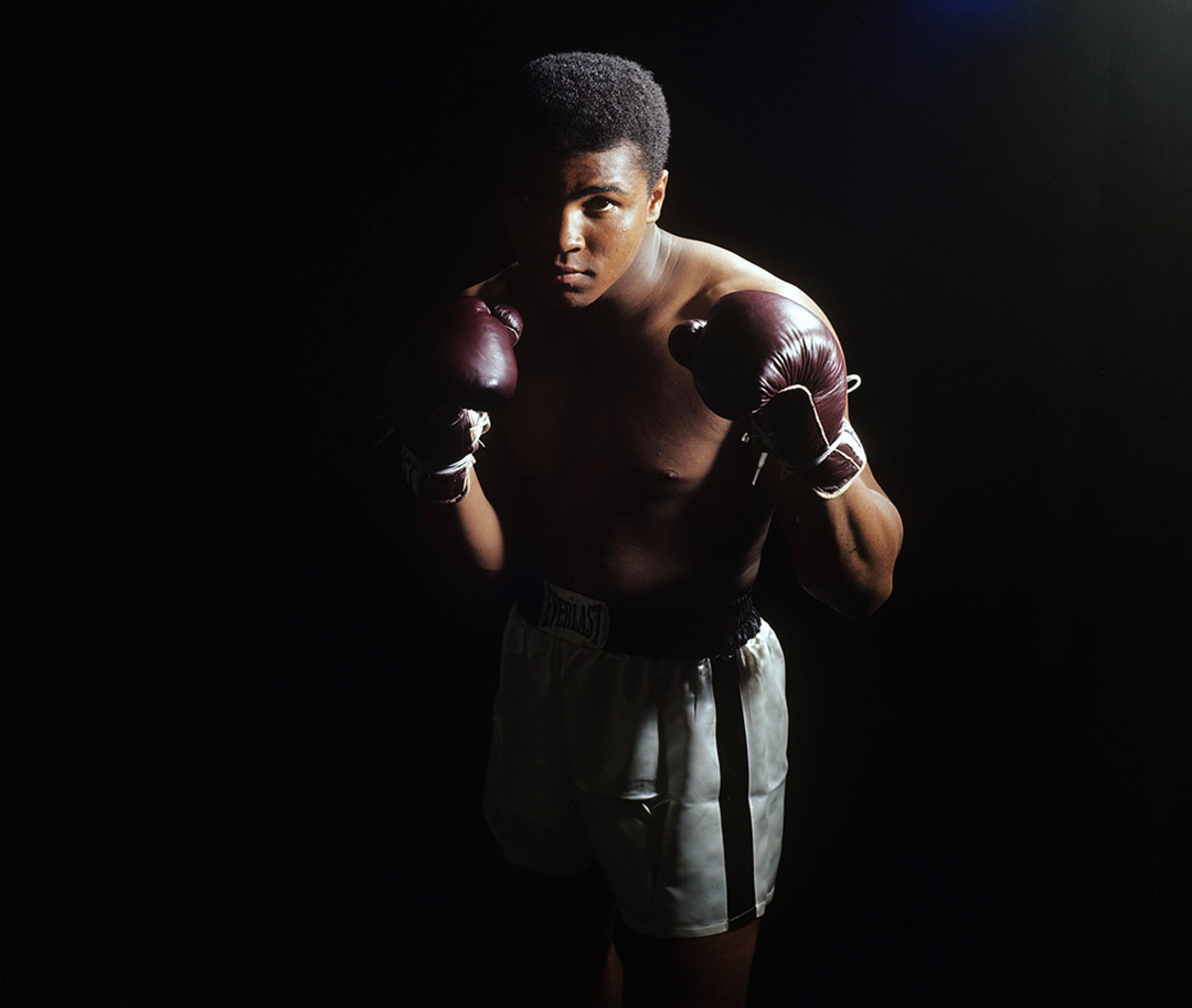

Draped in shadow, the young king — now known as Muhammad Ali — stared down the camera during a photo shoot in April 1965, one month before his rematch against Sonny Liston.

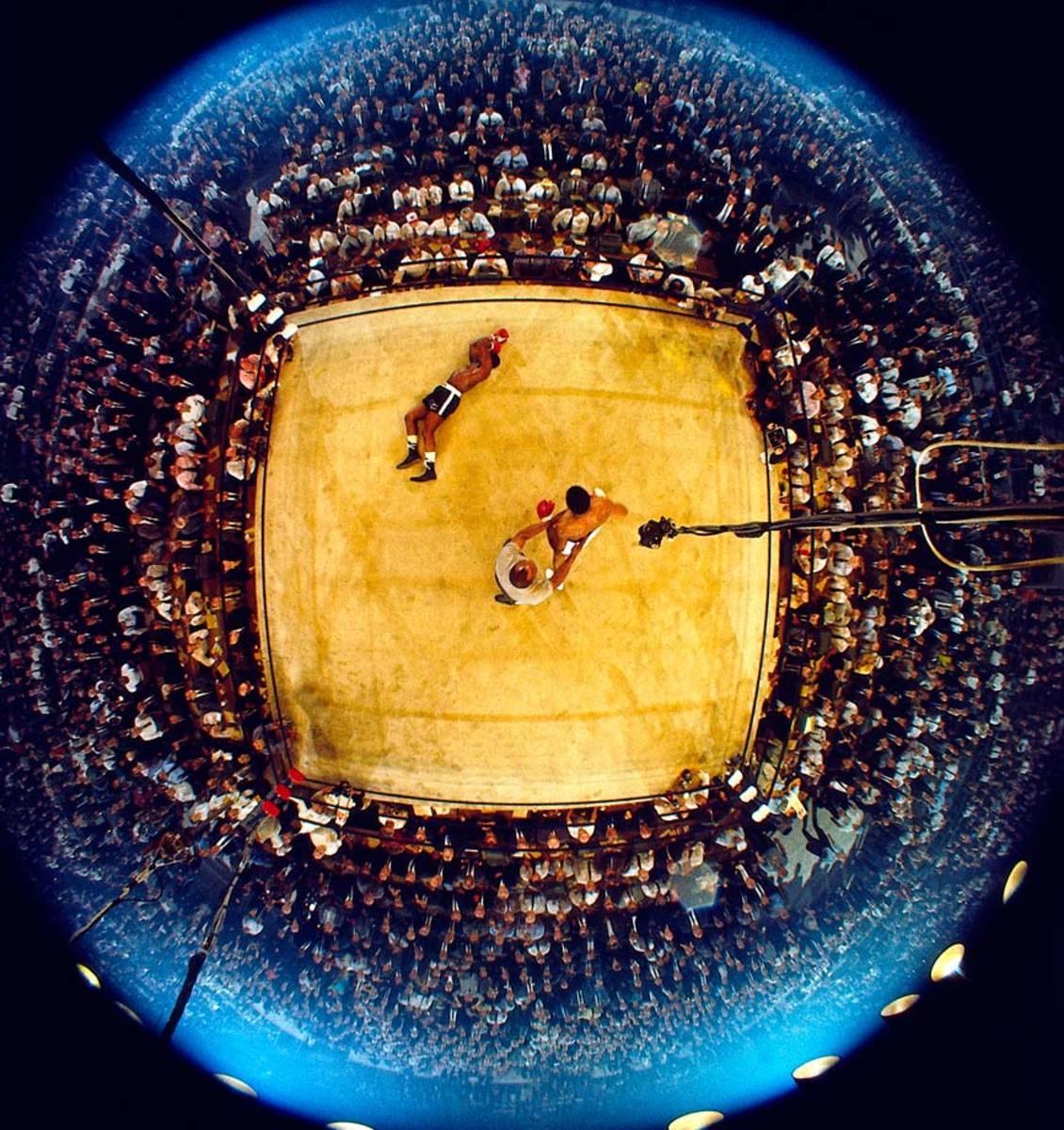

As Liston lingered on the canvas and the referee, former heavyweight champ Jersey Joe Walcott, tried to control Ali, the 2,434 spectators on hand in the Lewiston, Me., hockey arena — a record low for a heavyweight championship fight — tried to make sense of what all that had happened in less than two minutes after the opening bell.

The celebration over Liston continued. In a chaotic ending, Ali was awarded a knockout when Nat Fleischer, publisher of The Ring, informed referee Jersey Joe Walcott from ringside that Liston had been on the canvas for longer than 10 seconds after Ali knocked him down. The bout remains one of the most controversial in boxing history, with many observers insisting that Liston took a dive.

Ali's second title defense came in November 1965, against former two-time heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson. During the build-up to the bout, the normally soft-spoken Patterson earned the new champ's wrath by refusing to call Ali by his Muslim name. At the weigh-in, Ali's glare made it clear that he intended Patterson to pay for the disrespect.

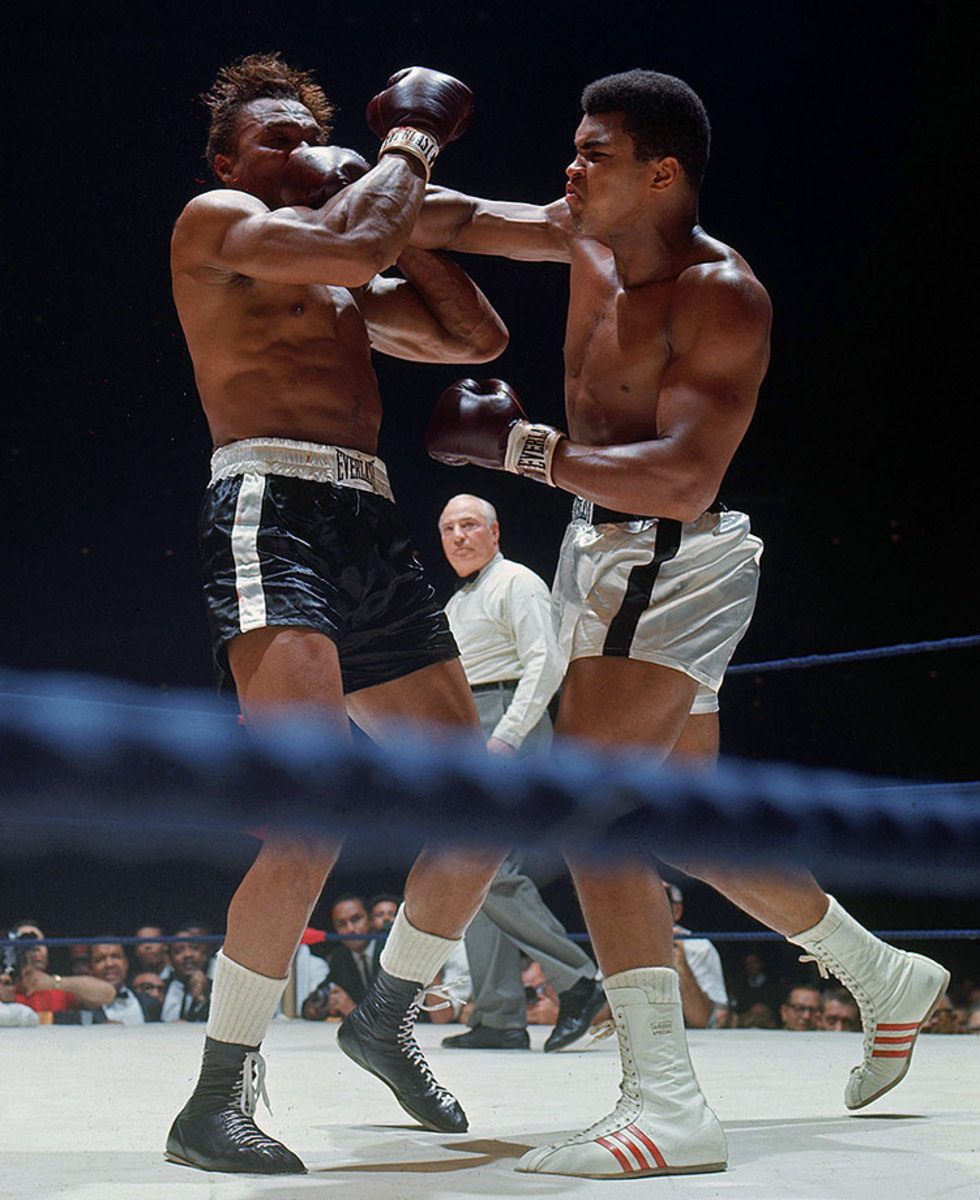

In cruelly efficient performance, Ali punished Patterson — who was hobbled by a painful back injury — seemingly toying with the former champ throughout the bout, hitting him at will and calling, "What's my name?" before finally winning on a 12th-round TKO.

Capping off a five-fight campaign in 1966, Ali faced Cleveland Williams in the Houston Astrodome on Nov. 14. Known as the Big Cat, the heavily-muscled Williams was a power puncher who had racked up 51 knockouts in 71 fights. But he was also 33, barely recovered from a gunshot wound sustained the year before, and up against a young champion very much in his prime. Ali wasted little time in unleashing a withering attack.

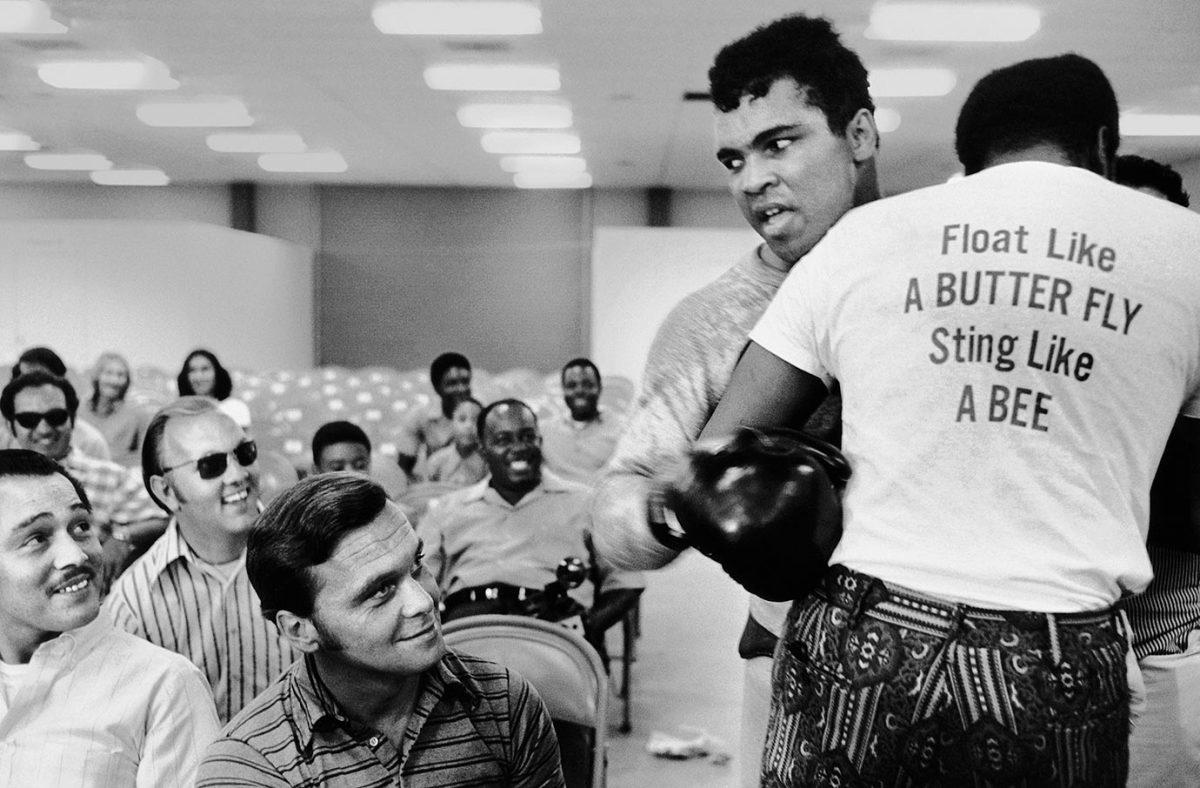

Float and sting: In a display of speed and combination punching unmatched in heavyweight history, Ali overwhelmed Williams from the start. The challenger, here down for the third time in round 2, would be saved by the bell before referee Harry Kessler could count him out, but it would only postpone the inevitable.

Ali dropped Williams again early in the third round, and Kessler waved the mismatch over at 1:08 of the third.

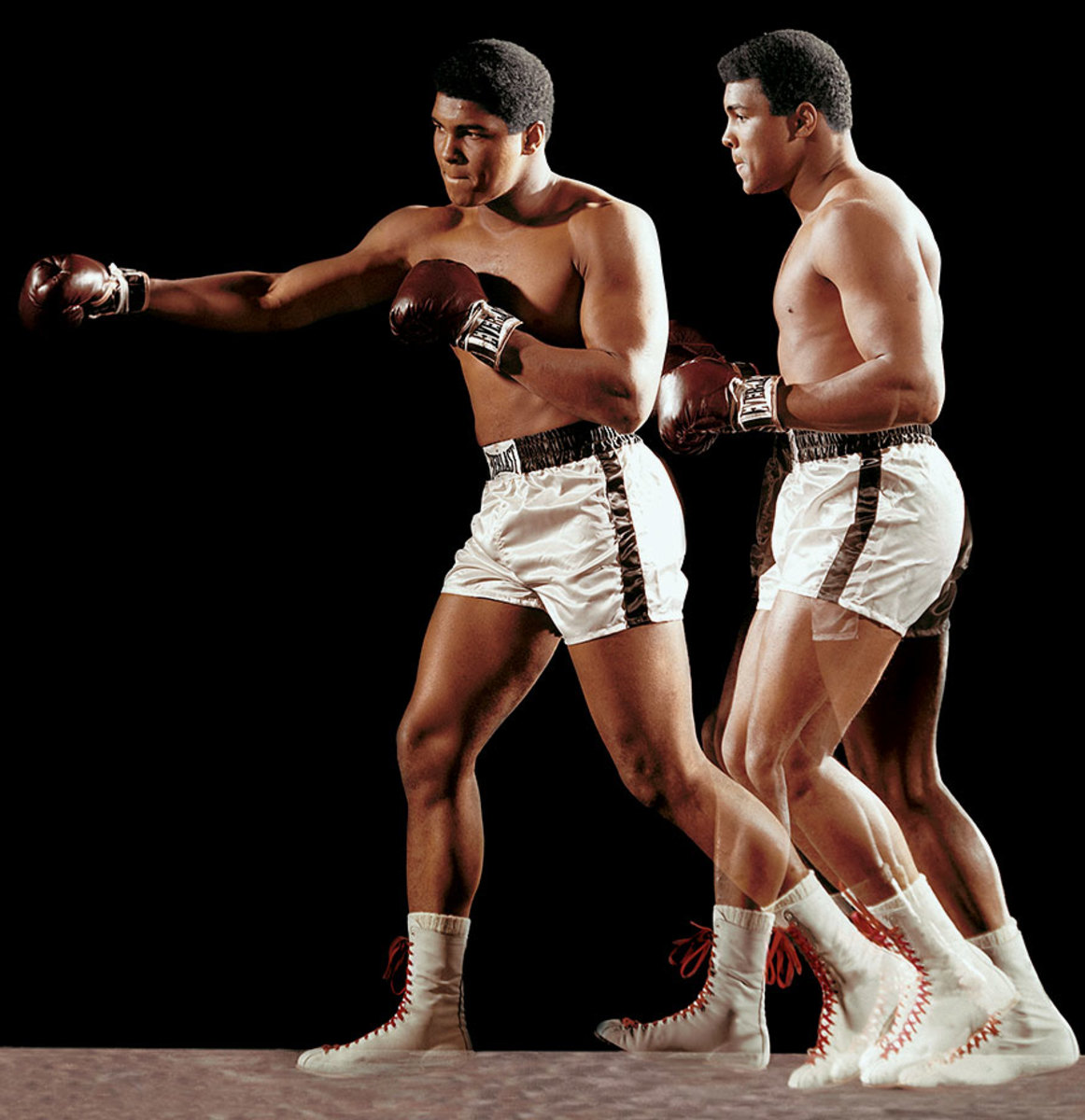

In a multiple-exposure portrait, Ali demonstrates his signature double-clutch shuffle during a photo shoot in December 1966.

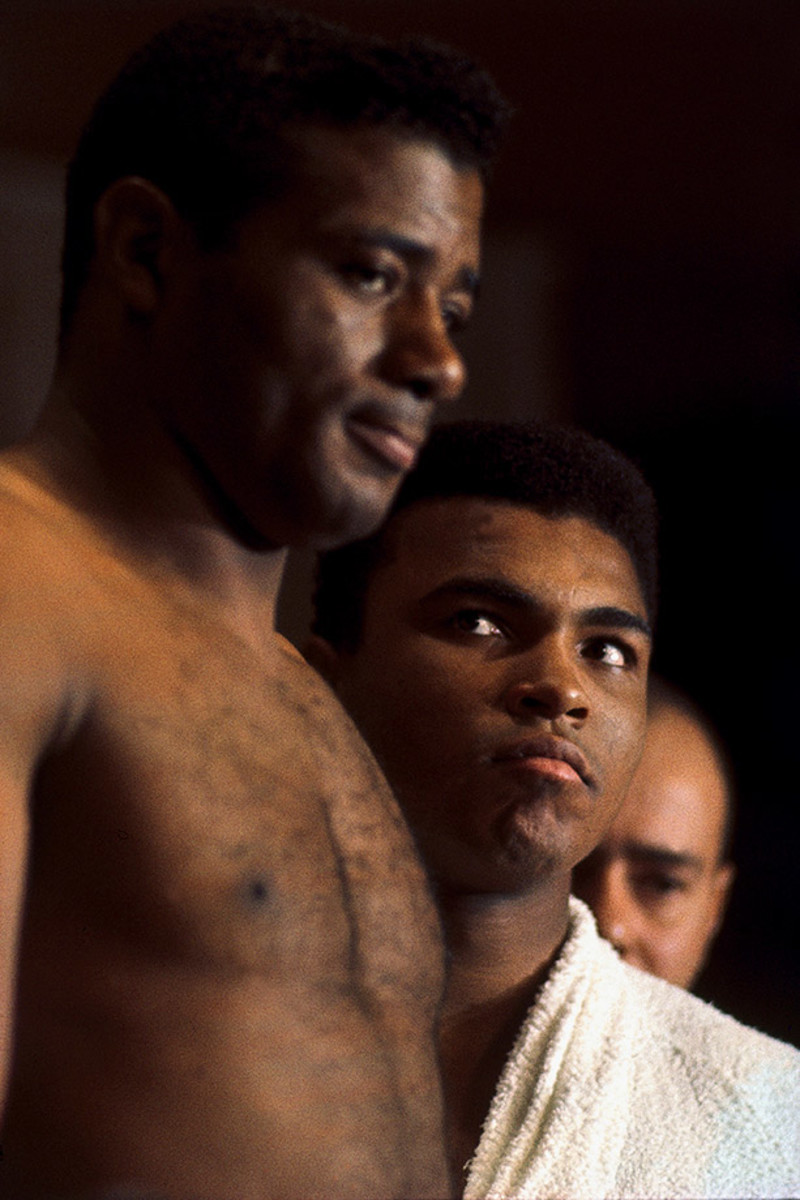

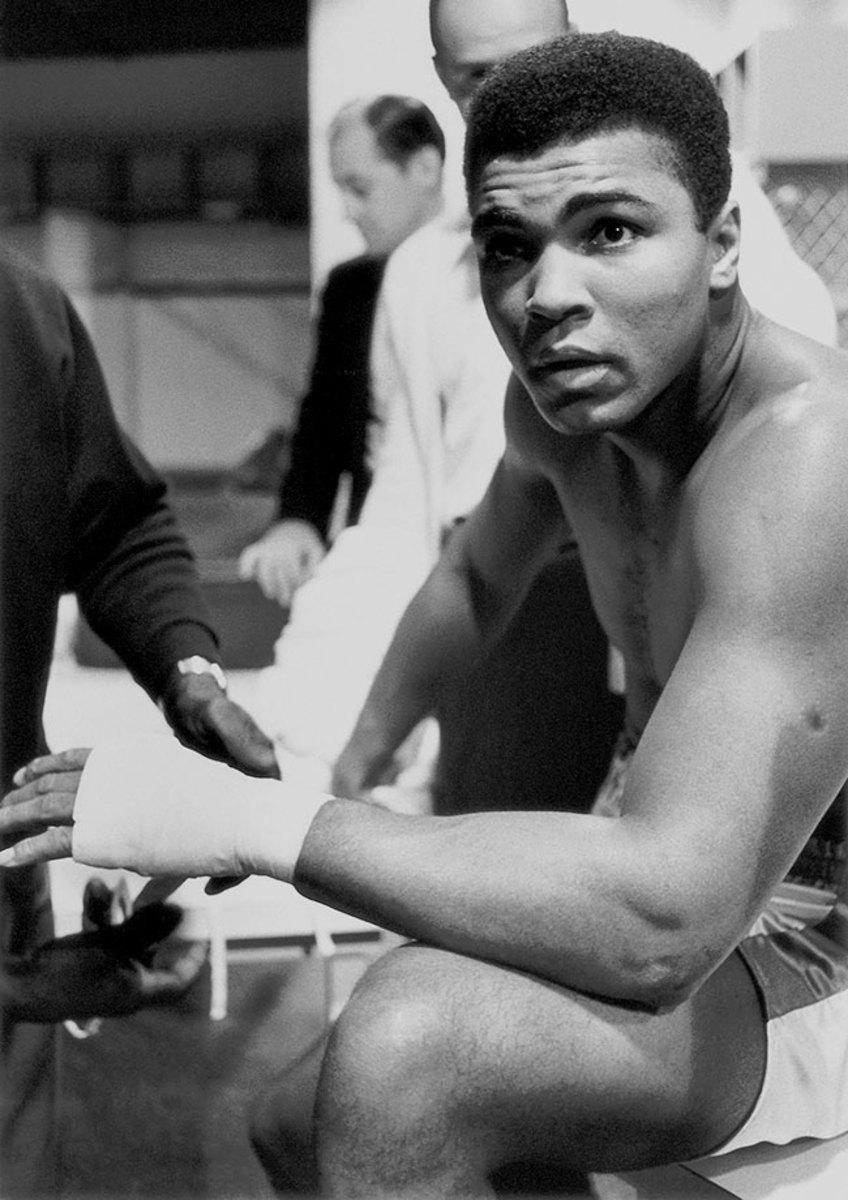

Ali sits in the locker room before his February 1967 fight against Ernie Terrell. Like Patterson before him, Terrell refused to call the champion by his Muslim name. Also like Patterson, he paid a stiff price, as Ali punished Terrell for 15 ugly rounds before winning by unanimous decision.

Outside the Armed Forces Examining and Entrance Station in Houston in April 1967, Ali spoke to the press about his refusal to be inducted into military service. Among those on hand was ABC's Howard Cosell, who would be a staunch supporter of the fighter's stance. The decision cost Ali his boxing license and his heavyweight title, and he was sentenced to five years in prison but remained free pending an appeal.

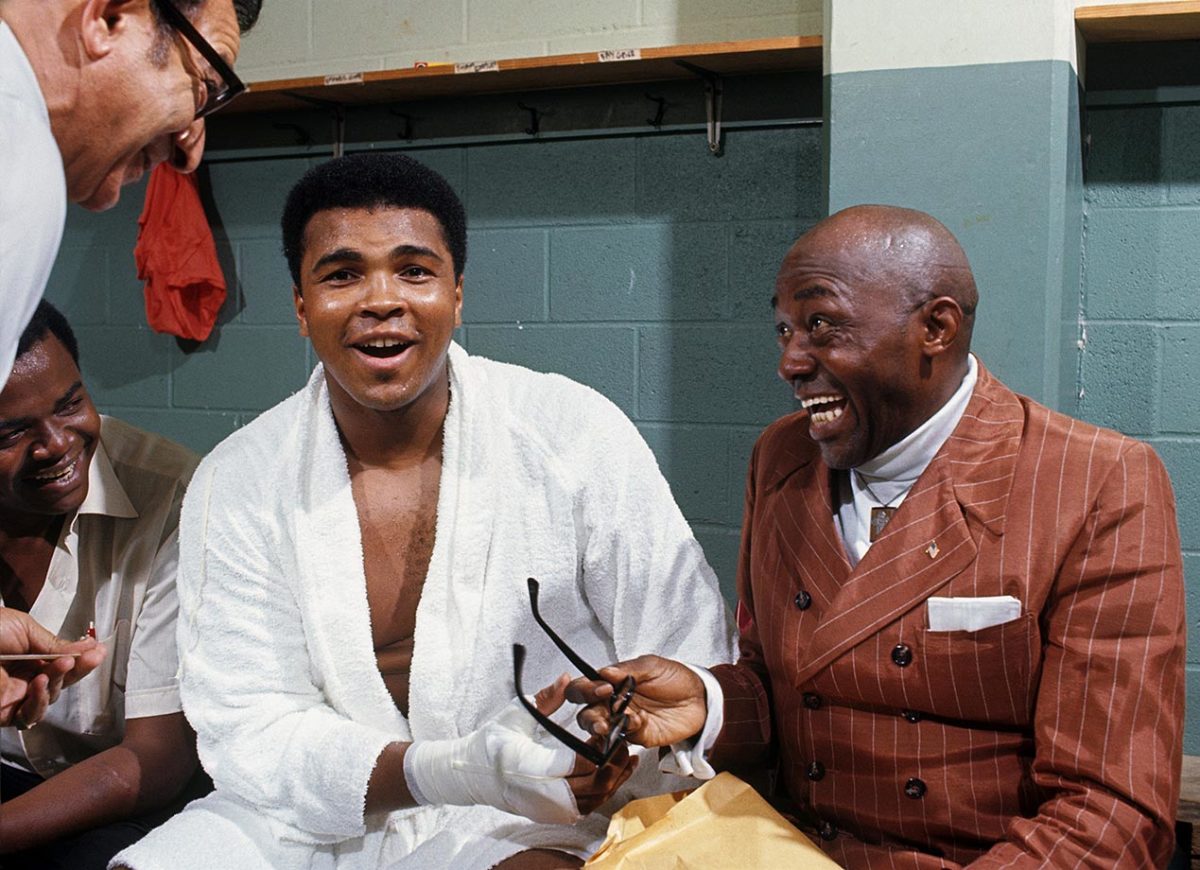

In professional exile for three and a half years because of his draft case, Ali sought to return to boxing in 1970. He began with a night of exhibition bouts at Morehouse College in Atlanta, where before going into the ring, he shared a locker room laugh with actor and comedian Lincoln Perry (right), better known by his stage name of Stepin Fetchit. The friendship between the two black icons would later be examined in an acclaimed play by Will Power, Fetch Clay, Make Man.

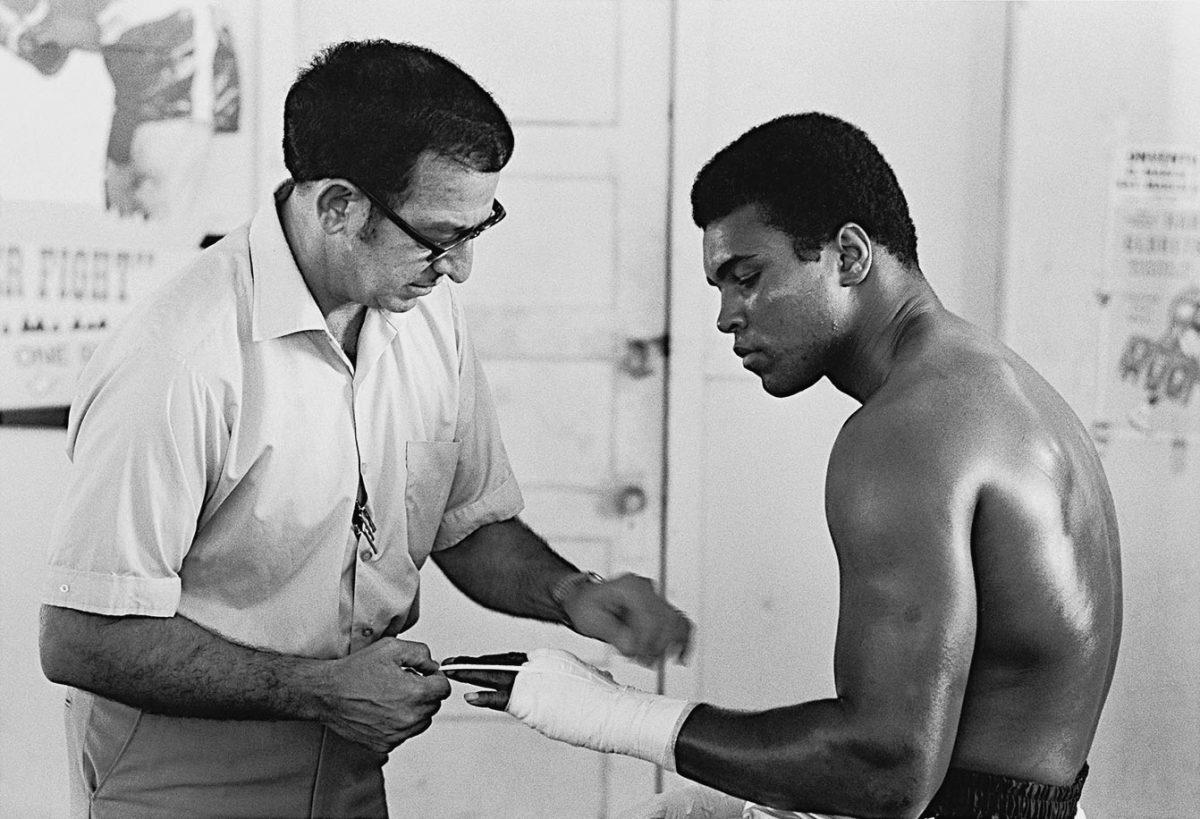

After the Atlanta Athletic Commission at last granted Ali a license, the deposed champion went back into serious training. He was, as ever, in the capable hands of trainer Angelo Dundee, here wrapping boxing's most famous fists at the 5th Street Gym in Miami in October 1970.

With his return to the ring scheduled for Oct. 26, 1970 in Atlanta, against dangerous contender Jerry Quarry, Ali made it clear to all who would listen that he was on a mission to reclaim the title that had been stripped of him.

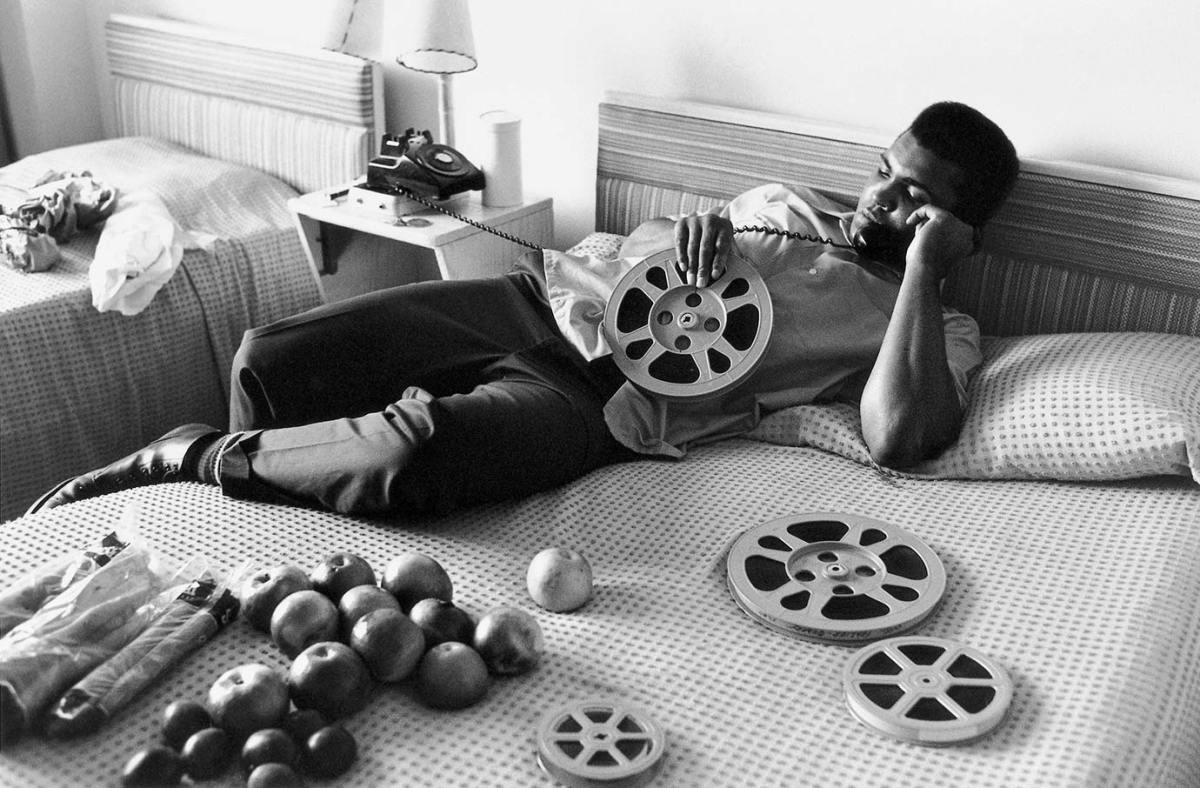

Reel to spiel: For the ever-loquacious Ali, even a rare moment of down time — like this afternoon in 1970 in a Miami hotel room — was a chance to do some talking.

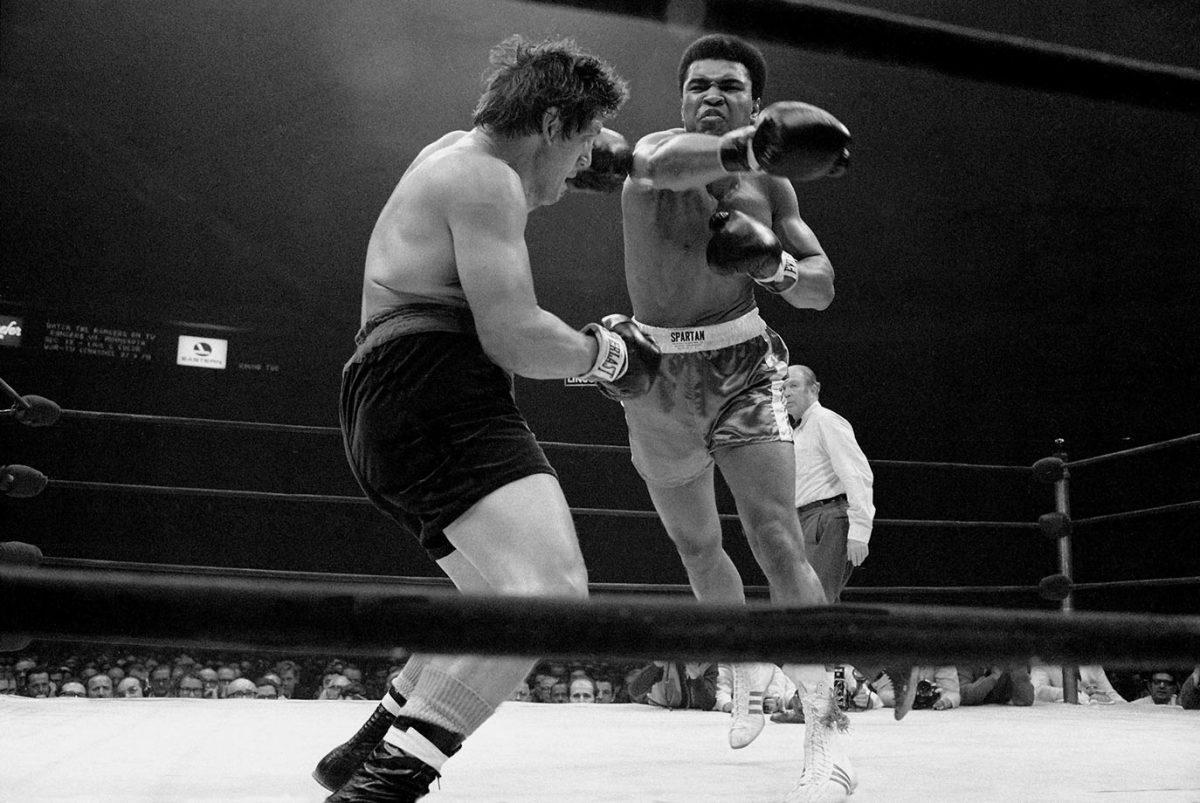

Despite Ali's long layoff, his comeback campaign would include no easy tune-up bouts. He stopped Quarry in three rounds on Oct. 26, 1970, then, just six weeks later — an unthinkably short interlude by today's standards — took on Argentine contender Oscar Bonavena in Madison Square Garden. Here, Ali fires a right at the rugged and awkward Bonavena, who took the fight to the former champion all night.

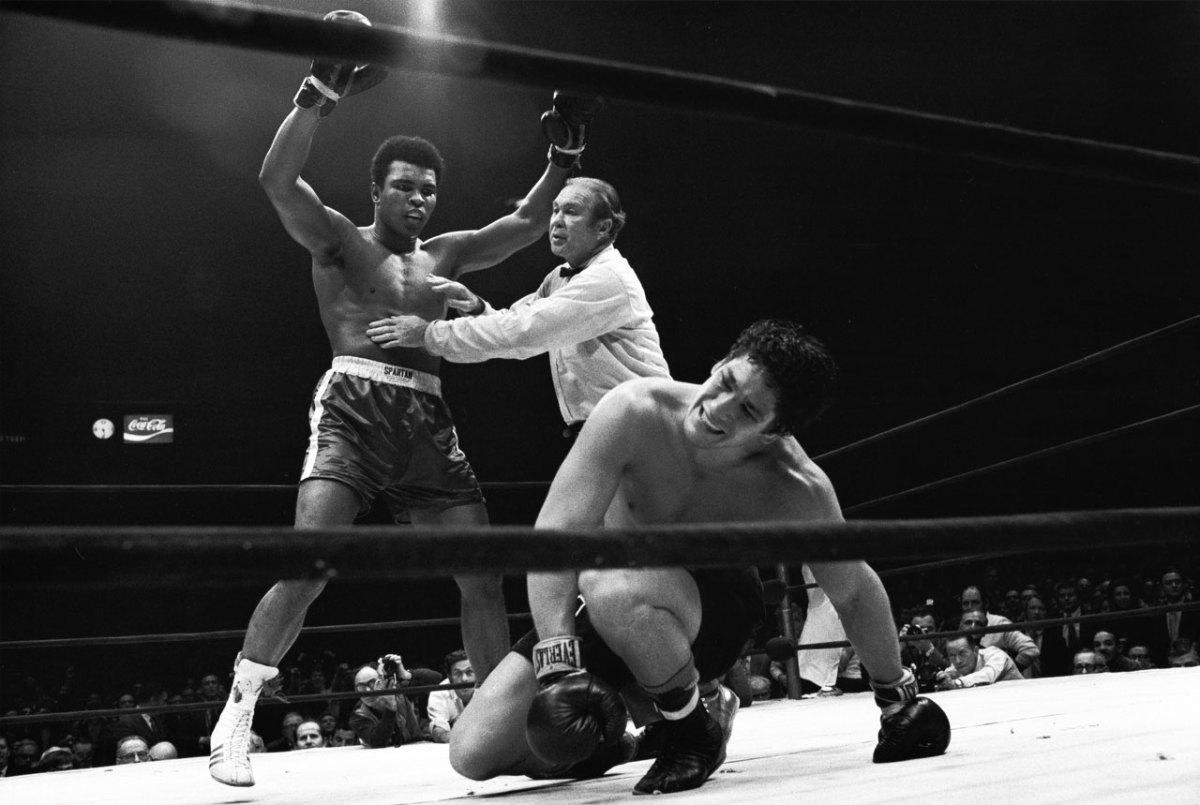

After a long, often sloppy bout, Ali — here being held back by referee Mark Conn — produced one of the most dramatic finishes of his career, dropping Bonavena three times in the 15th and final round to automatically end the fight. The win cleared the way for a showdown with Joe Frazier, the man who had taken the heavyweight title in Ali's absence.

On the night of March 8, 1971, the eyes of the world were on a square patch of white canvas in the center of Madison Square Garden. There, Ali and Joe Frazier met in what was billed at the time simply as The Fight, but has come to be known, justifiably, as the Fight of the Century. For 15 rounds the two undefeated heavyweights battled at a furious pace, with each man sustaining tremendous punishment. In the end Frazier prevailed, dropping Ali in the final round with a tremendous left hook to seal a unanimous decision and hand The Greatest his first loss in 32 professional fights.

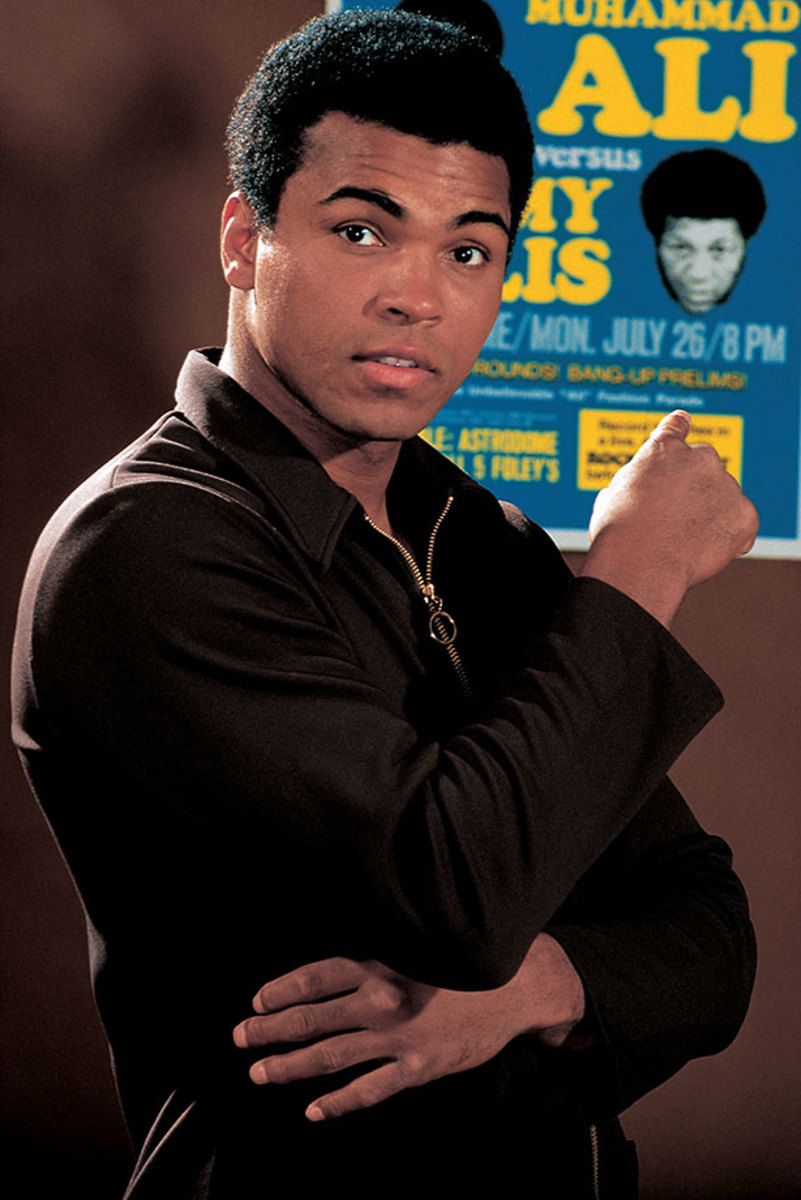

Ali poses with the fight poster for his upcoming fight against Jimmy Ellis during a photo shoot in July 1971. Ellis was an old friend of Ali's — both were trained by Angelo Dundee — and knew his fighting style well from many rounds of sparring.

For those sportswriters lucky enough to cover Ali on a regular basis, each day brought surprises and, more often than not, plenty of laughs. of Trainer Drew Bundini Brown helps Ali train for his fight against Ellis. Ali won the bout by technical knockout in the 12th round to claim the vacant NABF heavyweight title.

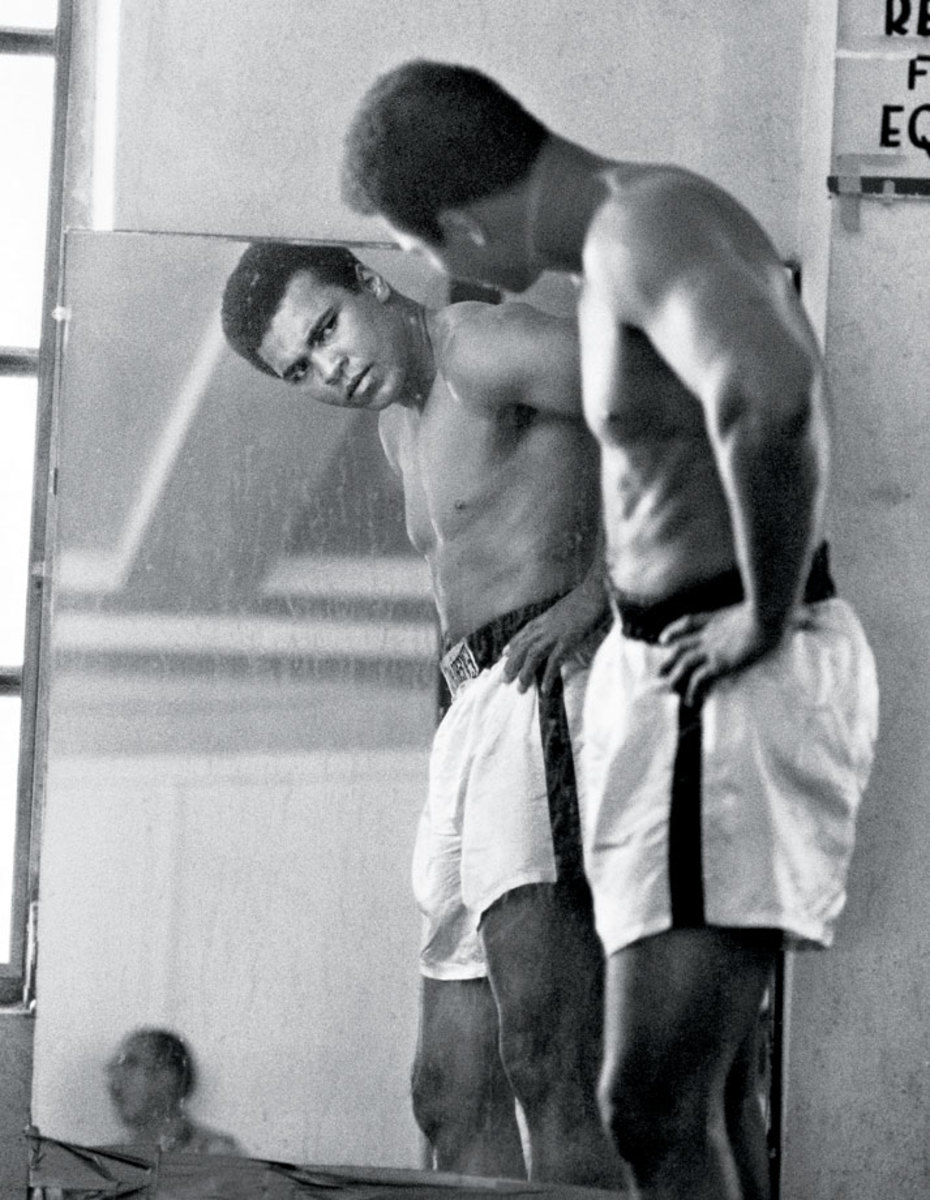

The man in the mirror stares back as Ali examines himself while training for a fight in 1972. He won all six of his fights that year.

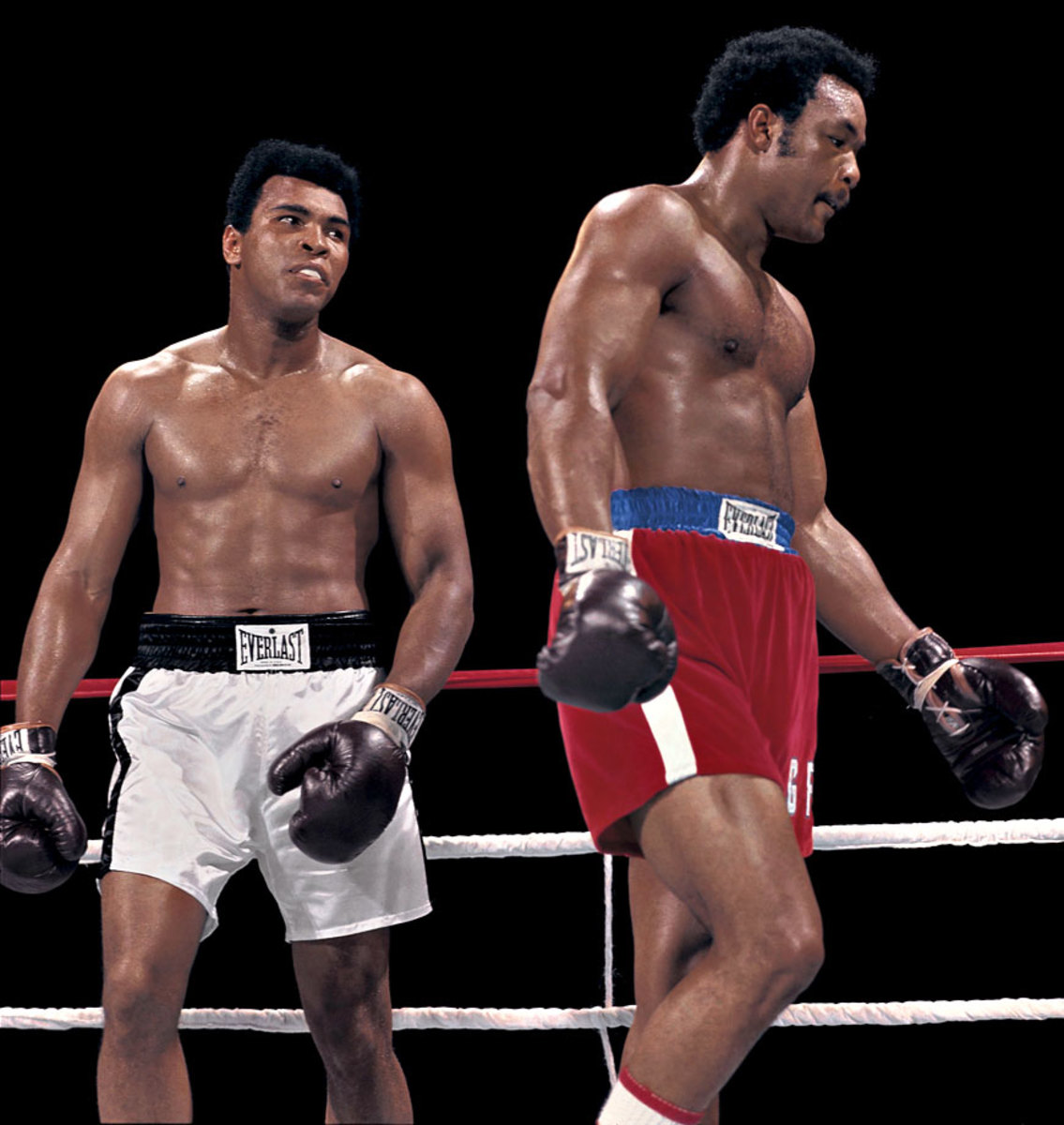

The Louisville Lip stands next to George Foreman before Ali's fight versus Jerry Quarry in June 1972. Ali won by technical knockout in the seventh round. Foreman at the time was 36-0. Ali would not get his shot against Foreman for more than two years.

Ali throws a left hook at Bob Foster in their 1972 fight at Stateline, Nev. Although Ali knocked Foster out, Foster did leave his mark: a cut above Ali's left eye, his first as a professional.

Foster lies on the canvas after getting knocked down by Ali. Ali knocked Foster down four times in the fifth round and twice more in the seventh round before he was finally counted out after Ali knocked him down again in the eighth round.

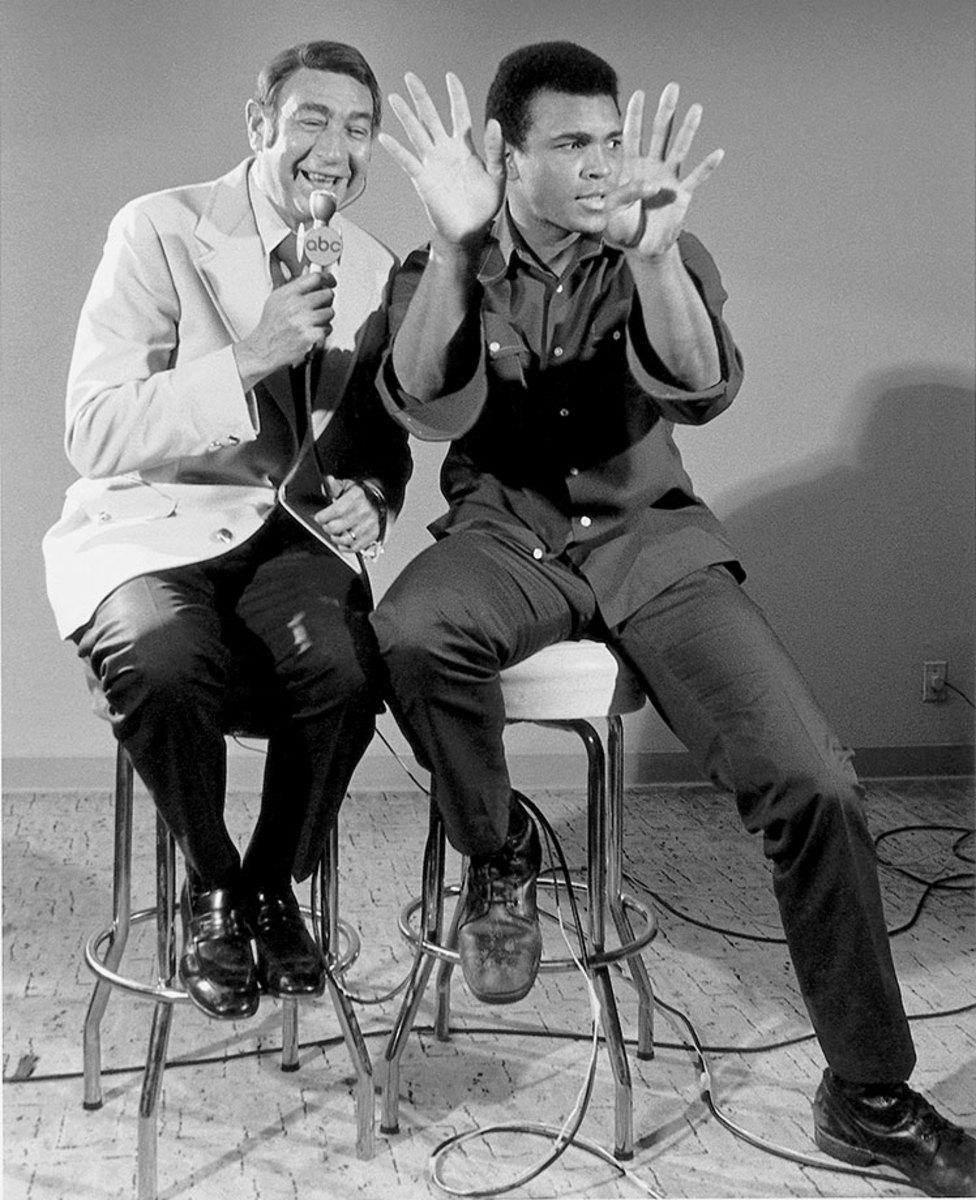

Ali sits with sportscaster Howard Cosell before his fight with Joe Bugner in February 1973. Although unable to knock Bugner out, Ali won comfortably by unanimous decision.

Ali hits a speed bag while warming up for his bout with Bugner in Las Vegas. Ali prepared ferociously for the fight, training 67 rounds the week leading up to the fight, including six rounds the day before the fight.

In a lighter pre-fight moment, Ali poses for a portrait wearing a hat in his dressing room before the match with Bugner.

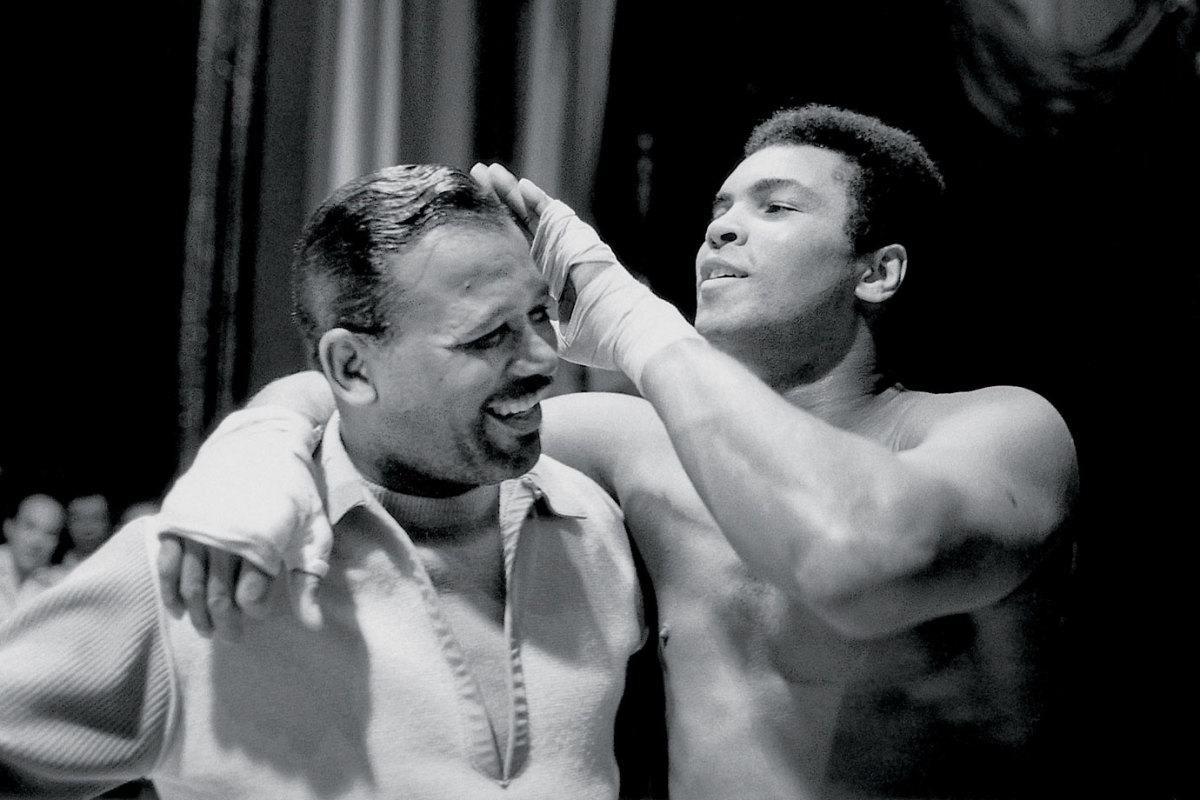

Ali plays with Sugar Ray Robinson's hair in the locker room before his bout with Bugner. The former welterweight and middleweight champion was Ali's childhood idol.

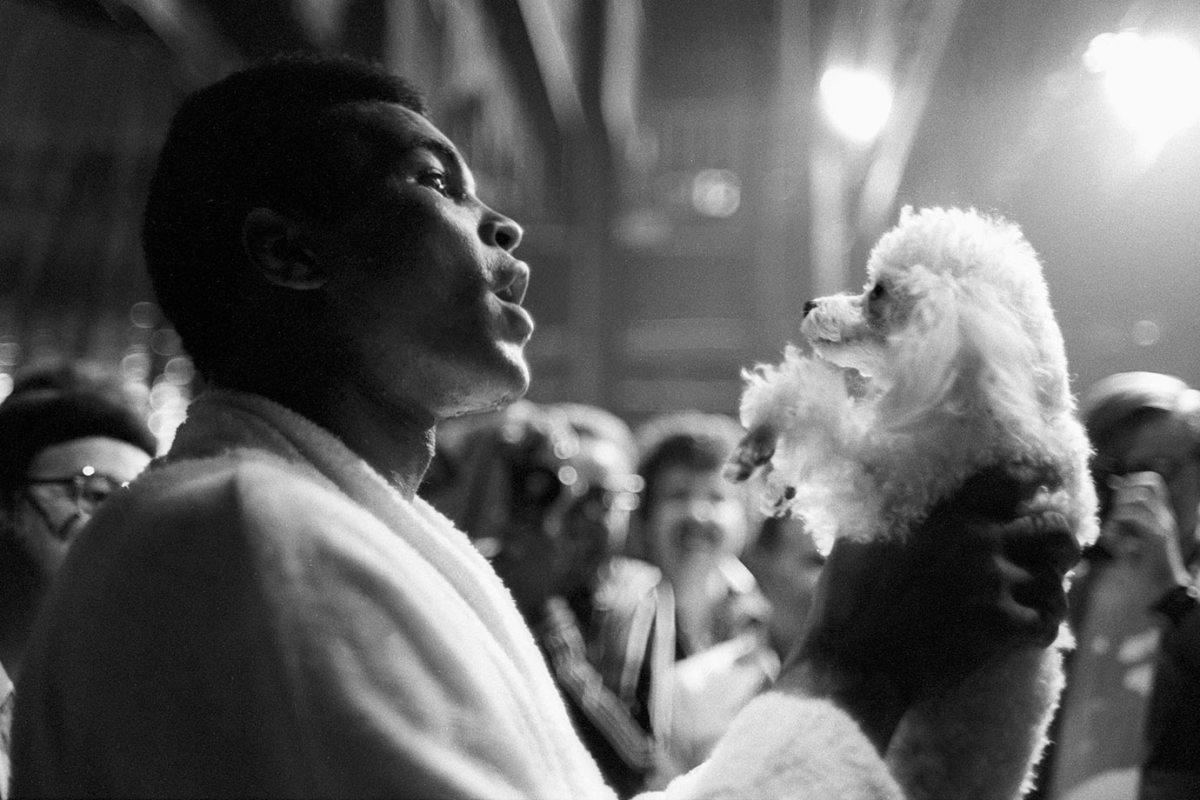

Before the fight with Bugner, Muhammad Ali enjoys a relaxed moment with a poodle at Caesars Palace Hotel. He won the fight with Bugner by unanimous decision.

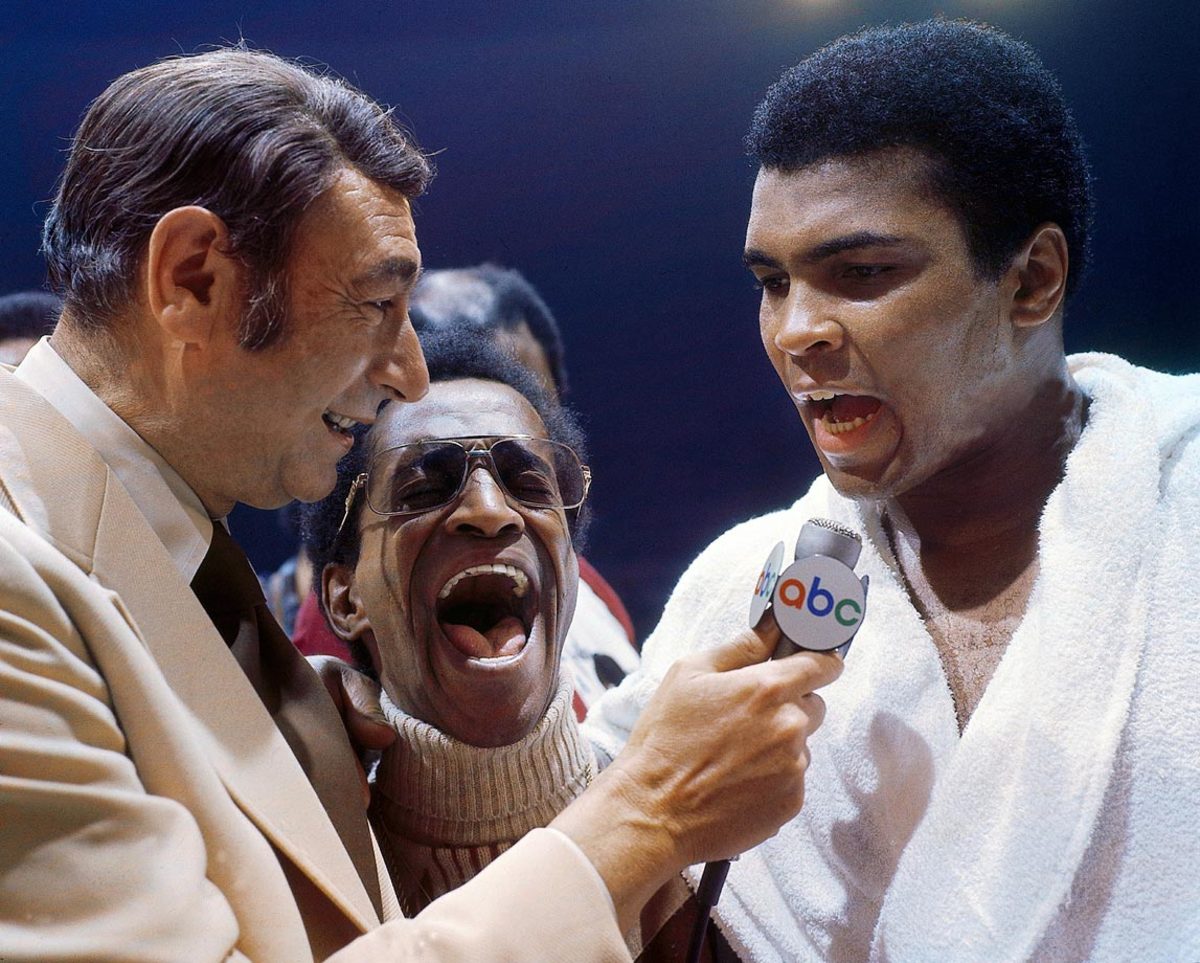

Howard Cosell interviews Ali, with entertainer Sammy Davis Jr. in the middle, after his victory over Joe Bugner by unanimous decision in. Although the fight was never in jeopardy of getting away from him, Ali praised Bugner's legs and said he could be a champion in a few years.

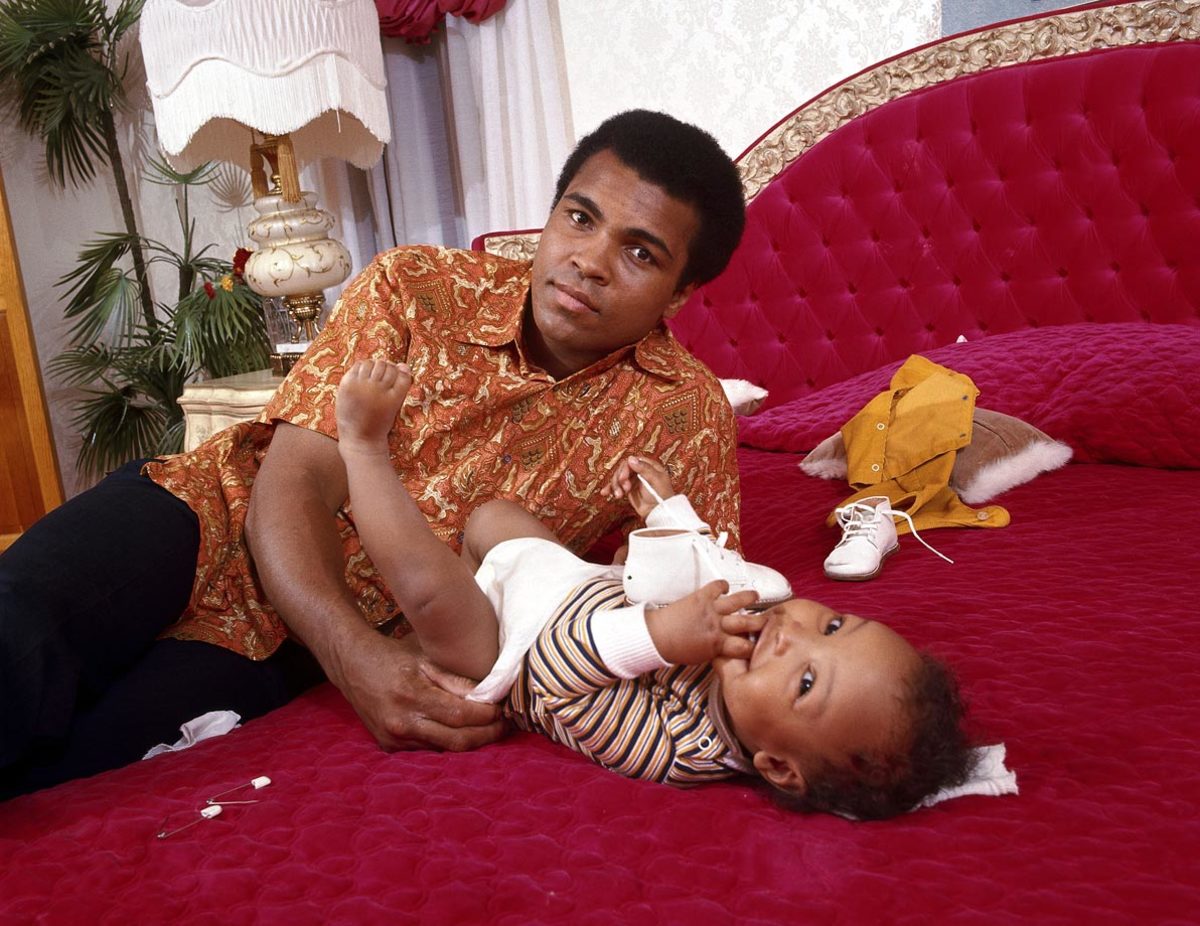

Ali changes the diaper of his son in his bedroom during a photo shoot at the family's home in April 1973. Ali had suffered a broken jaw less than a month earlier in his fight against Ken Norton.

In the wake of his split decision loss to Norton, Ali plays with his son in his bedroom at home in Cherry Hill, N.J.

Ali kisses his daughter Jamillah outside of their home following the loss to Norton, just the second defeat of his career.

The Ali family standing outside their New Jersey home. To the right of Muhammad Ali are his twin daughters, Jamilllah and Rasheda, daughter Maryum and his wife, Khalilah, holding their son Ibn Muhammad Ali Jr.

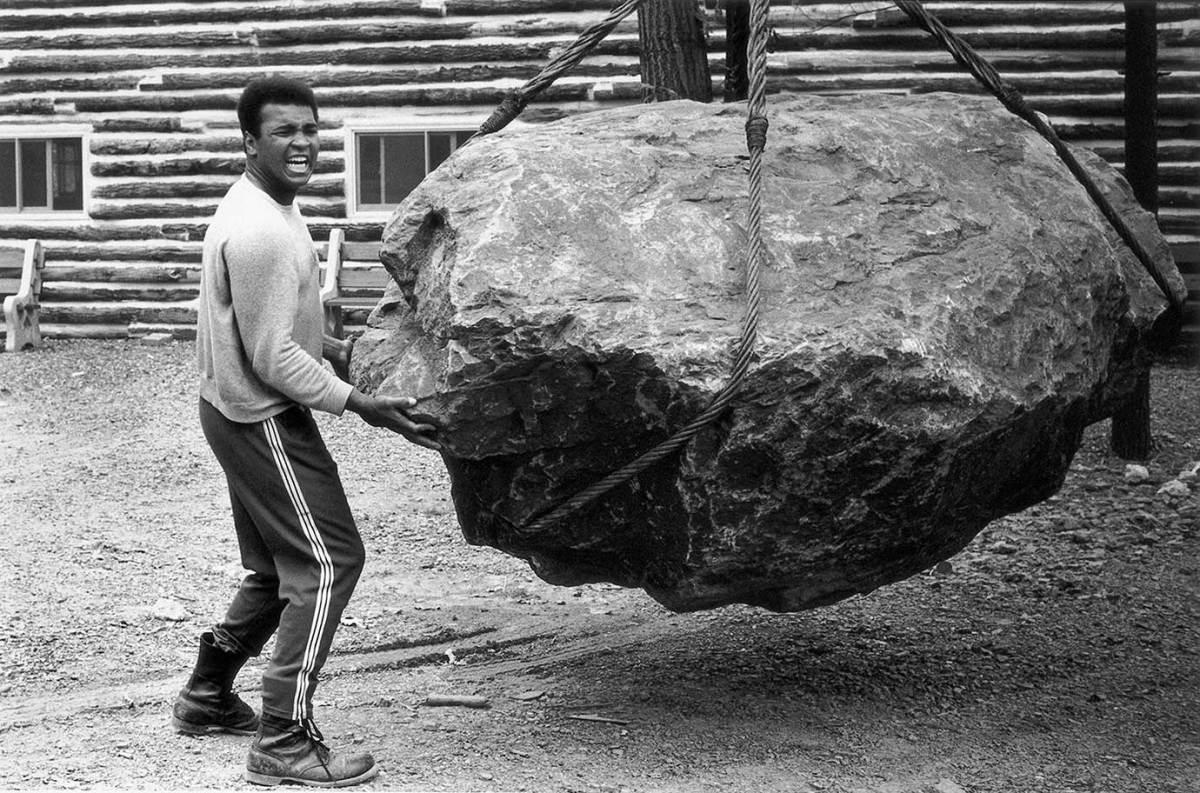

At his training camp cabin, Ali pushes a boulder during a photo shoot in Deer Lake, Penn., in August 1973. Ali was training for his rematch against Ken Norton, who broke his jaw five months earlier.

Ali chops wood at his cabin in Deer Lake. He referred to the training camp as "fighter's heaven" and used it to prepare for fights away from the spotlight.

The fighters weigh in on the Tonight Show with Johnny Carson ahead of Ali and Ken Norton's September 1973 fight.

Johnny Carson listens to Ali on the Tonight Show three days before his rematch with Norton. Ali would avenge his earlier loss to Norton, winning a narrow split decision.

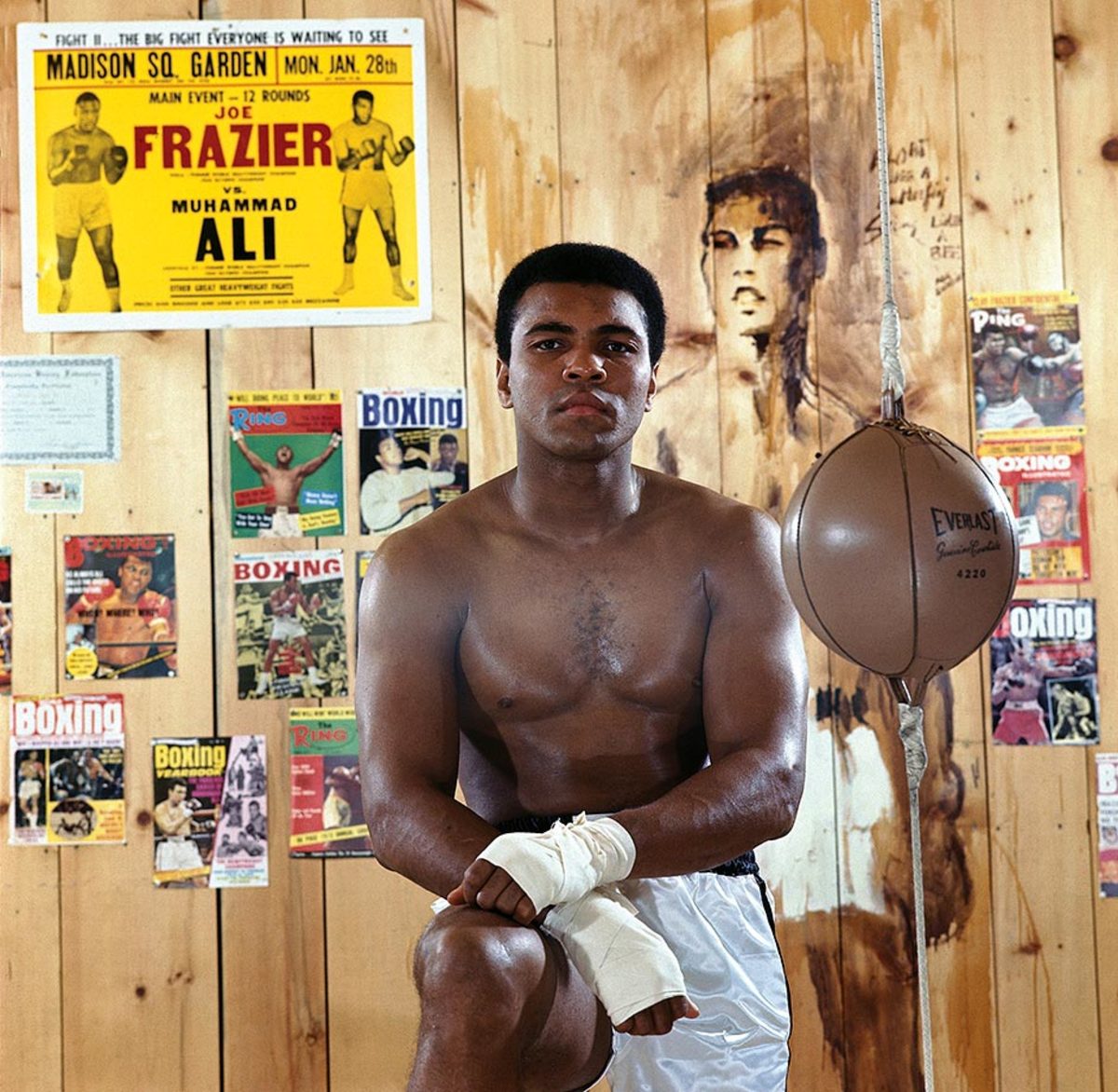

Ali poses in front of posters and magazine covers from throughout his career at his training camp cabin in Deer Lake in 1974.

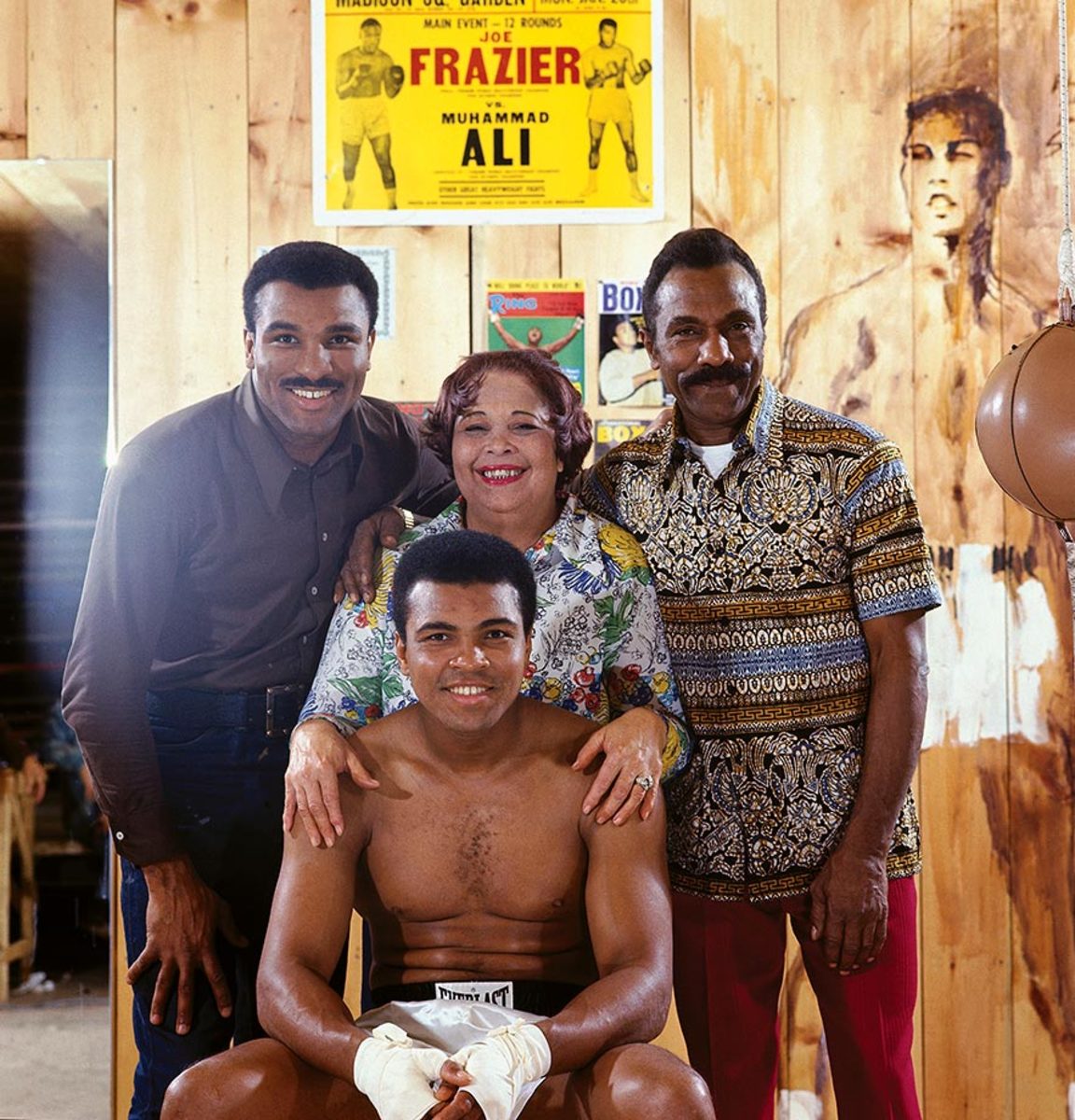

Ali poses with members of his family in front of a poster from his first fight with Joe Frazier. Ali's brother, Rahman Ali; mother, Odessa Clay; and father, Cassius Clay Sr. stand behind the boxer.

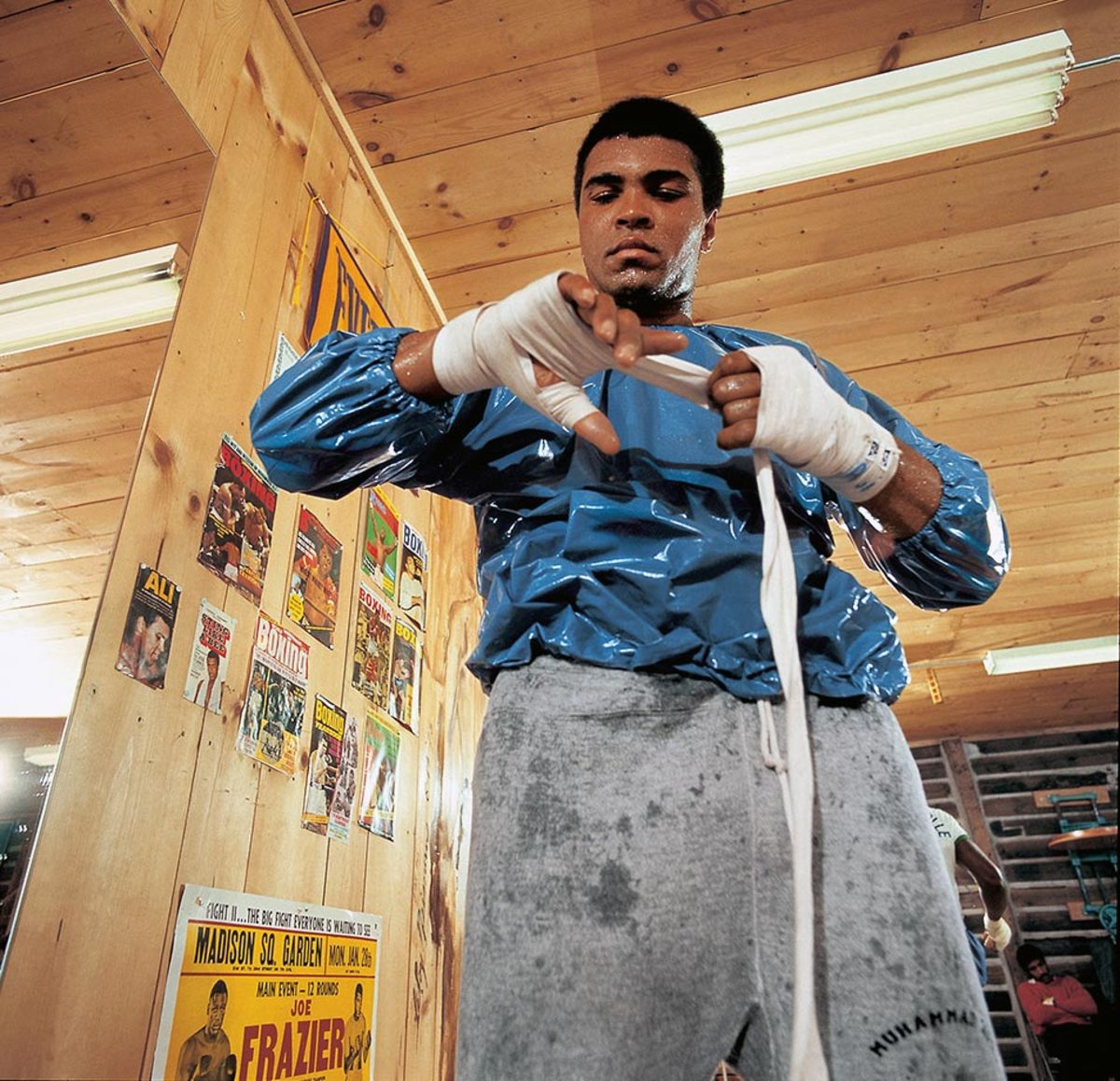

Less than three weeks before his rematch with Joe Frazier on Jan. 28, 1974, Ali wraps his hands while wearing a sauna suit at his training camp cabin.

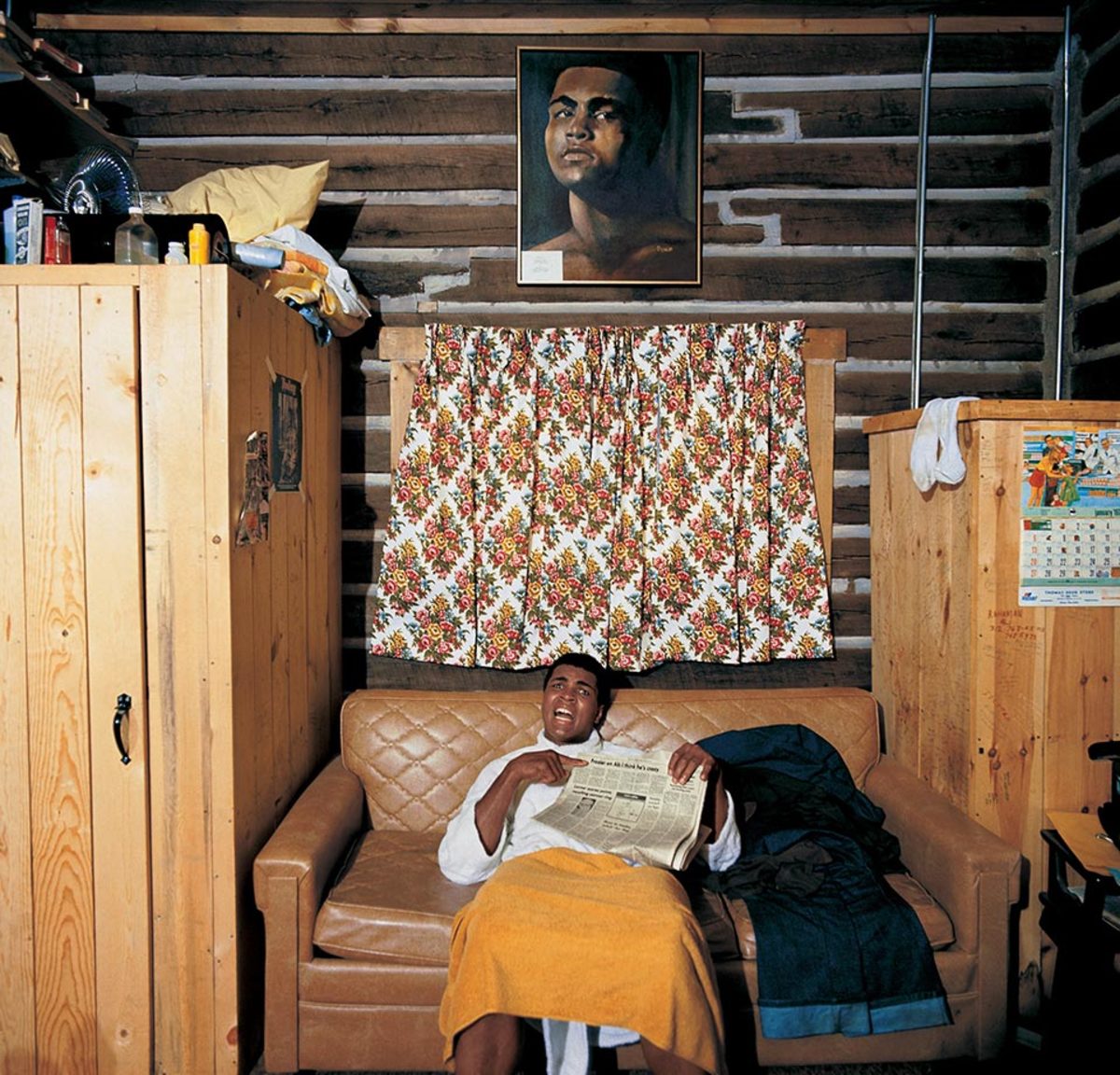

Ali holds a newspaper at his cabin in January 1974. He is pointing to a headline that reads, "Frazier On Ali, I Think He's Crazy." Ali and Frazier fought for the second time later that month with Ali winning by a unanimous decision.

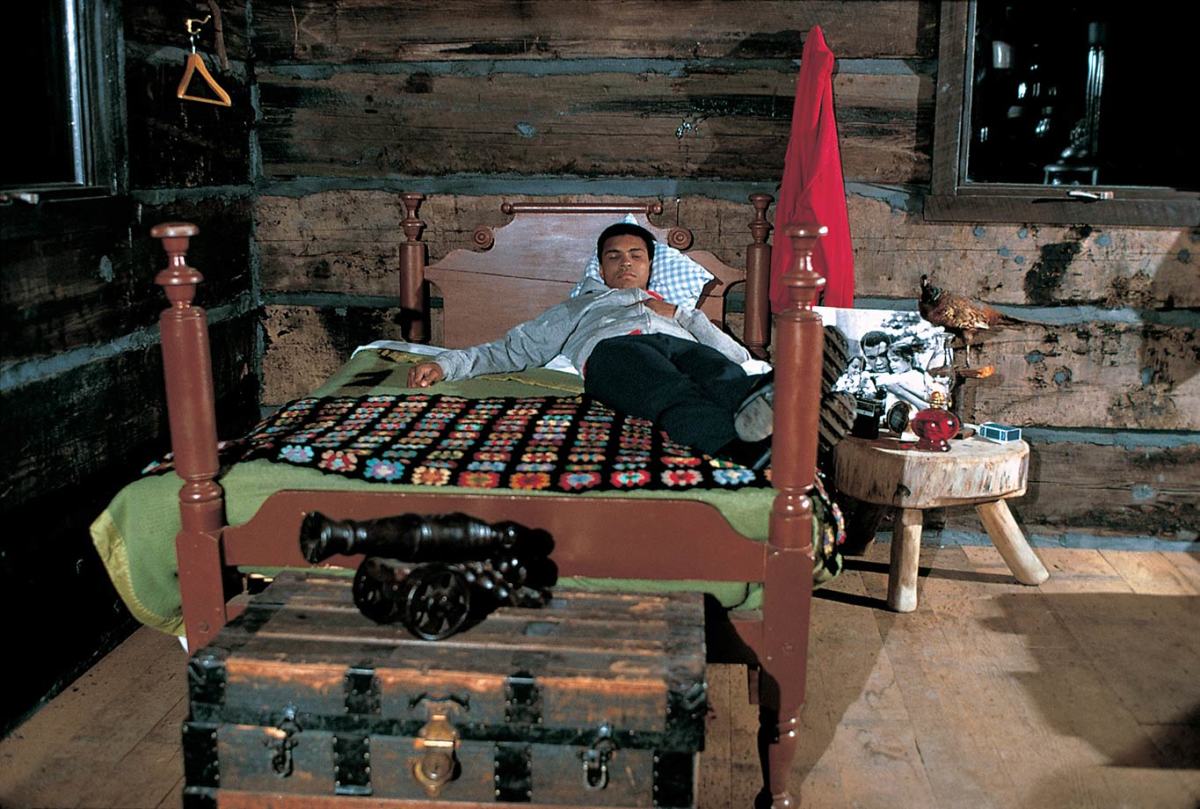

Ali lies on his bed at his cabin during the January 1974 photo shoot.

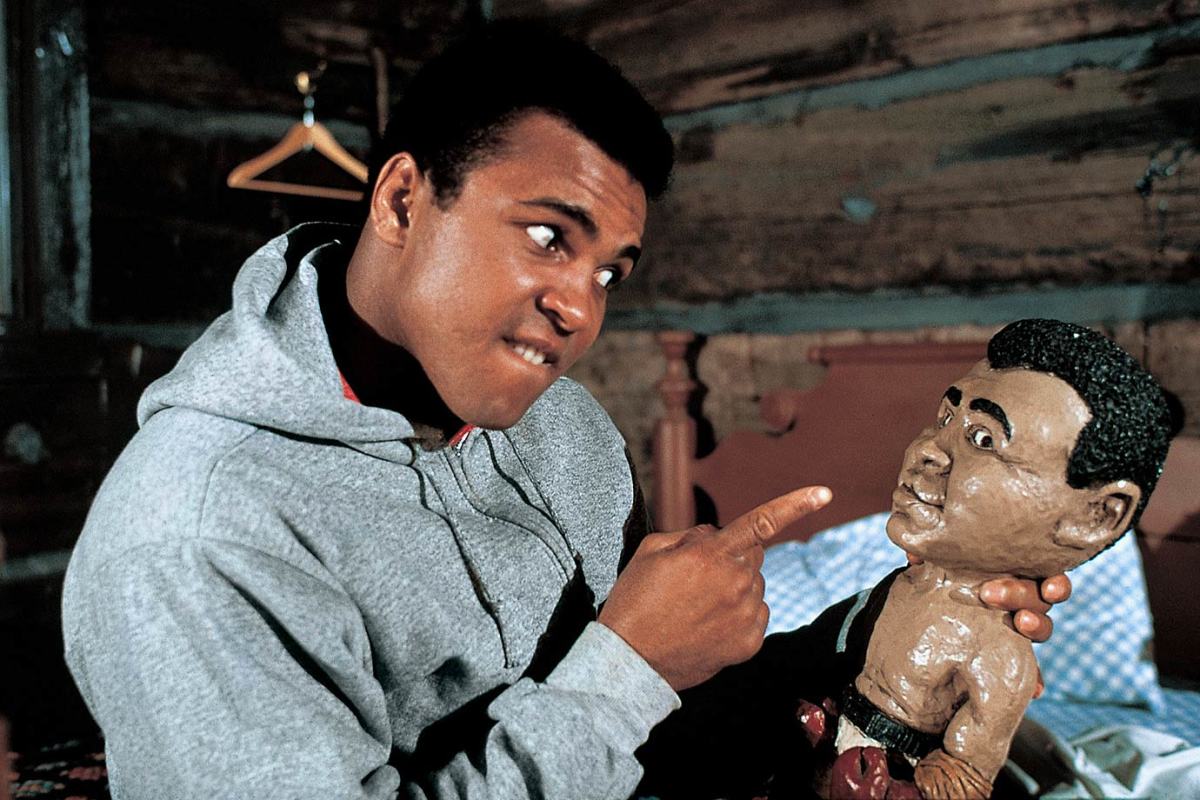

His smaller incarnation stares straight back as Ali plays with a doll of himself during the same 1974 shoot at his training camp cabin.

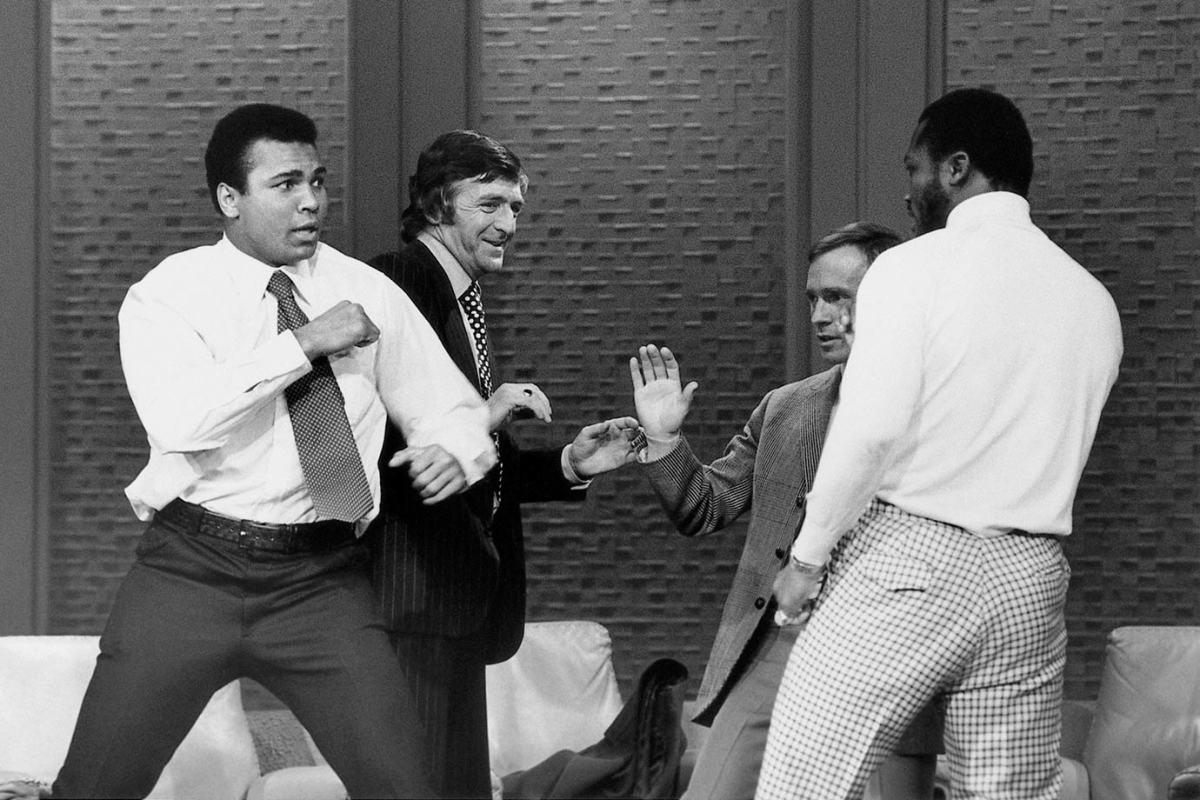

Ali and Joe Frazier fight on the set of The Dick Cavett Show while reviewing their 1971 bout in advance of their 1974 rematch. Ali called Frazier ignorant, to which Frazier took exception. As the studio crew tried to calm Frazier down, Ali held Frazier by the neck, forcing him to sit down and sparking a fight. The television set fight amped up anticipation of their January 1974 bout.

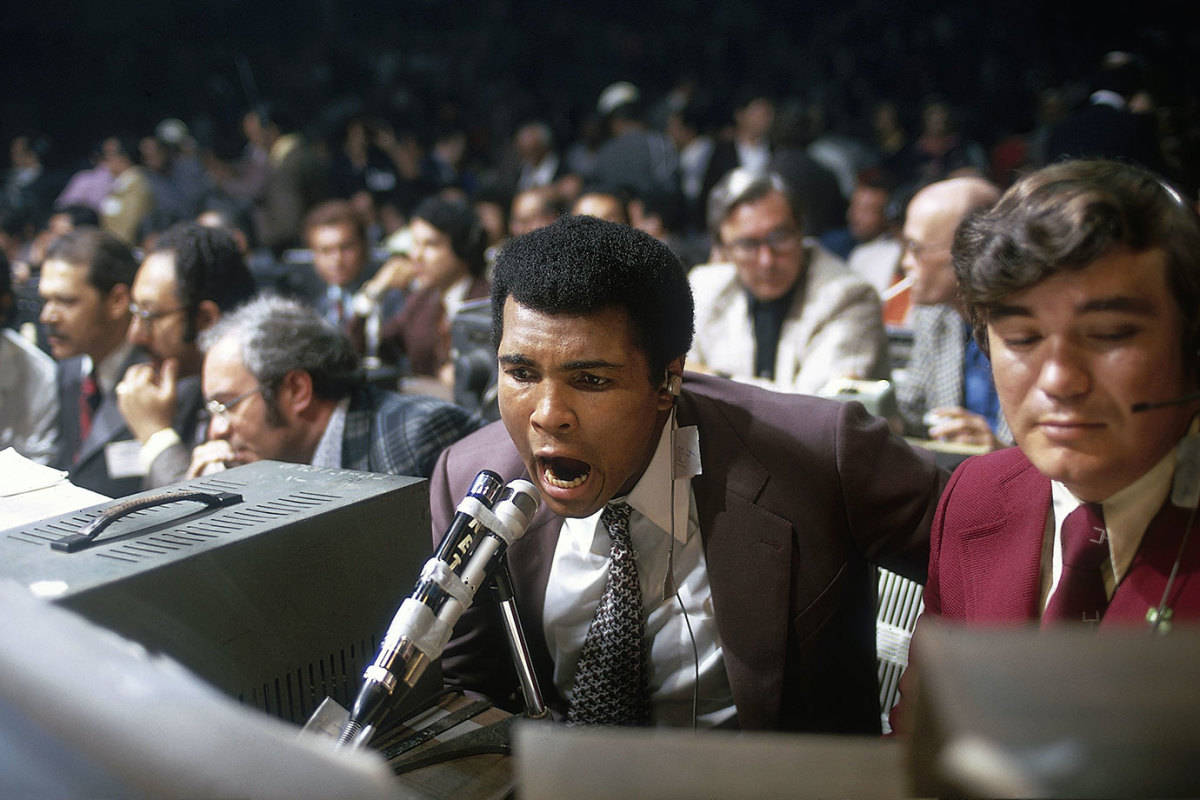

Exploring a different side of the sport, Ali broadcasts the fight between George Foreman and Ken Norton in March 1974. Foreman won the fight by technical knockout in the second round, setting up the showdown with Ali in Zaire.

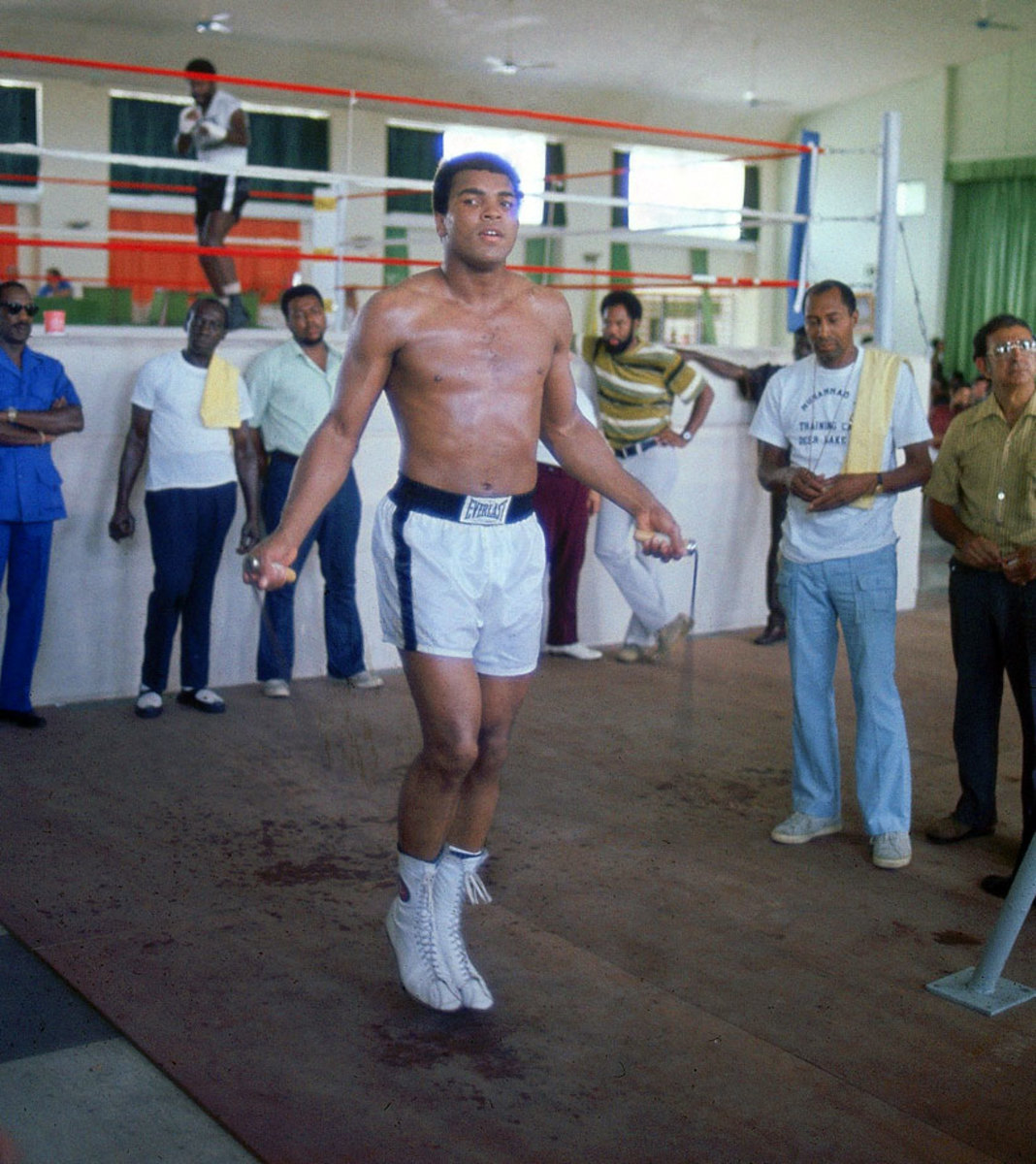

Ali jumps rope at the Salle de Congres in Kinshasa, Zaire, while training for his heavyweight title fight against George Foreman. Both Ali and Foreman spent most of the summer of 1974 training in Zaire to adjust to the climate.

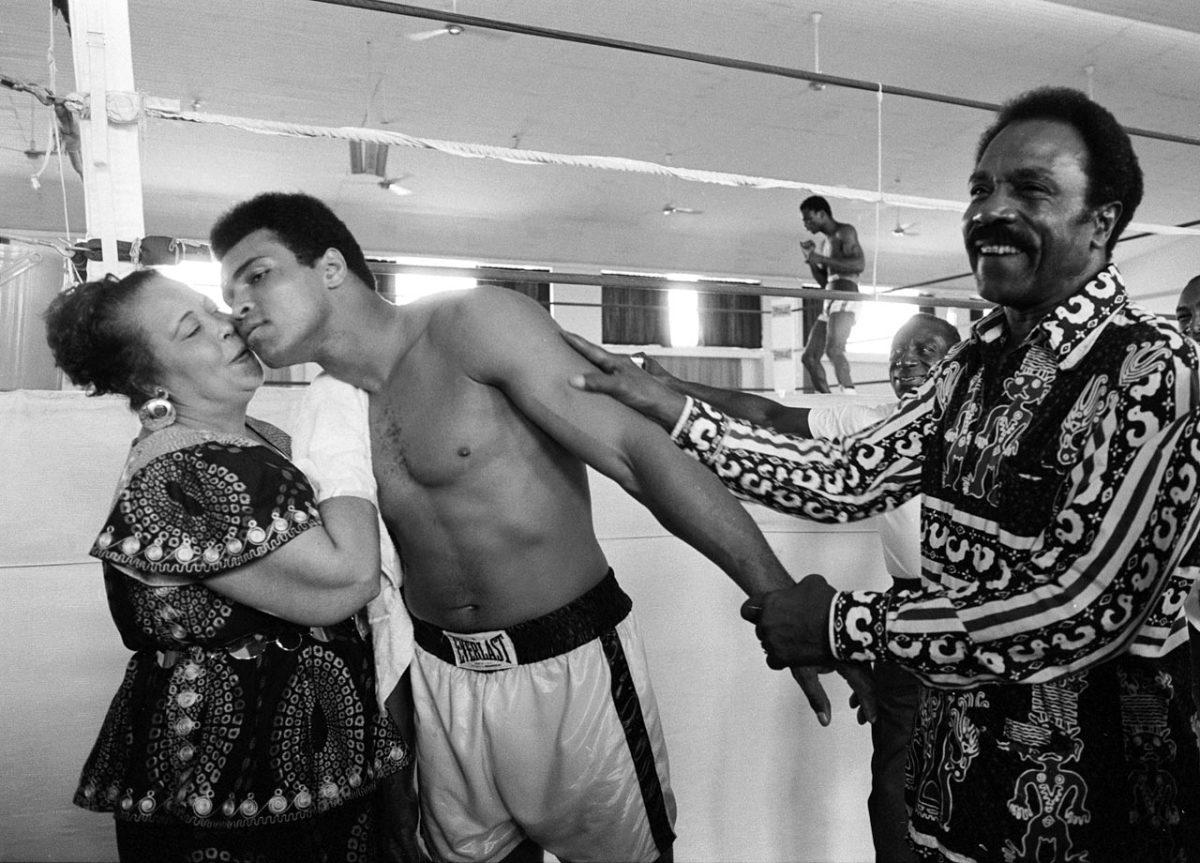

While training before his fight with George Foreman, Ali kisses his mother, Odessa Clay, while his father, Cassius Clay Sr., looks on. Ali's superior strategy and ability to take a punch led him to his upset victory as he absorbed body blows from Foreman before he responded with powerful combinations to Foreman's head.

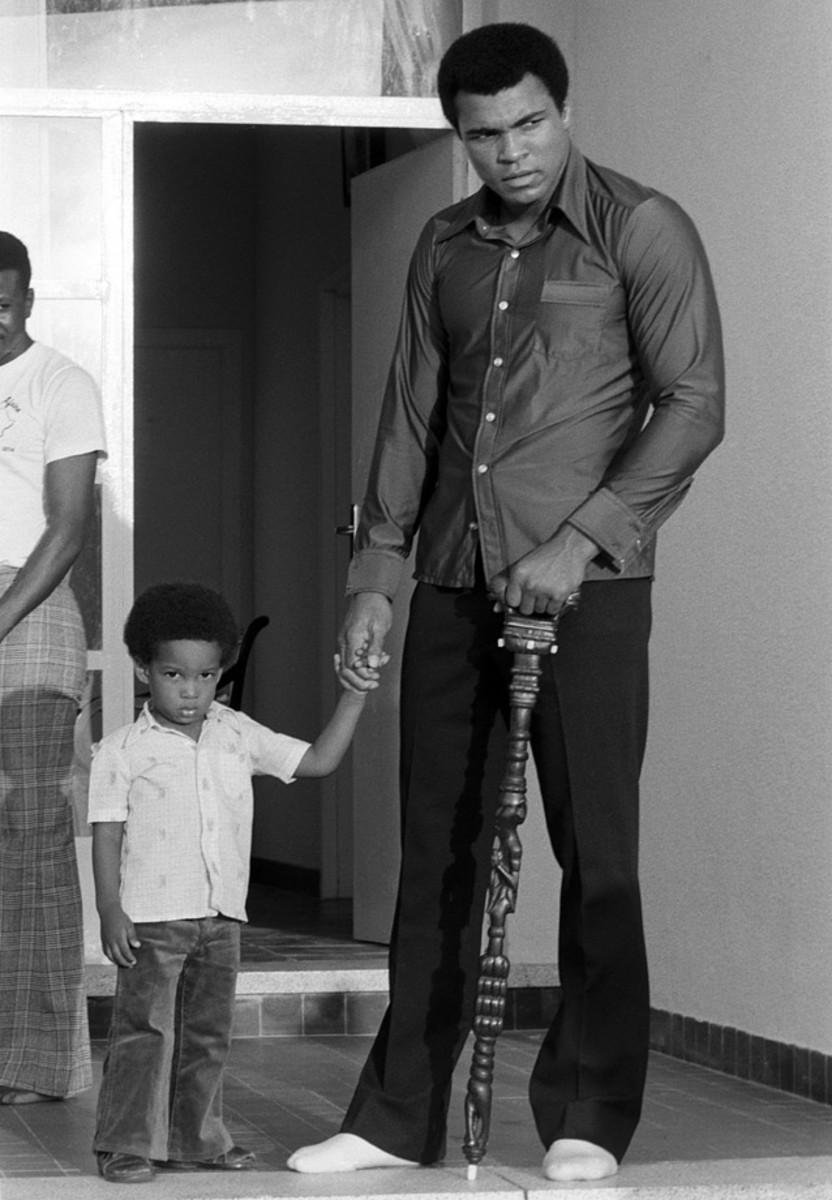

Four days before the fight, Ali holds the hand of his son Ibn in Zaire. Ali successfully courted the favor of the Zaire crowd, prompting chants of "Ali bomaye!" — translated as "Ali, kill him!"

Ali poses in front of the Le Militant statue at the presidential complex that was the site of Ali's January heavyweight title bout with Foreman. The fight was originally set for a month earlier, but Foreman suffered a cut near his eye during training, forcing a delay.

Ali stands against the railing on the River Zaire watching the sunset four days before the Rumble in the Jungle. The fight was sponsored by Zaire to achieve the $5 million purse promoter Don King had promised both Ali and Foreman.

Before employing his famous rope-a-dope strategy against Foreman, Ali makes a face at the camera. Ali allowed Foreman to throw many punches but only into his arms and body, and when Foreman tired himself out from the mostly ineffective punches, Ali took control of the fight.

Ali points before his bout with Foreman. The victory over his favored opponent made him the heavyweight champion of the world for the first time since he was stripped of his titles in 1967.

Ali stares at George Foreman during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali earned his shot at the heavyweight title by defeating Joe Frazier in January 1974, avenging a loss three years earlier.

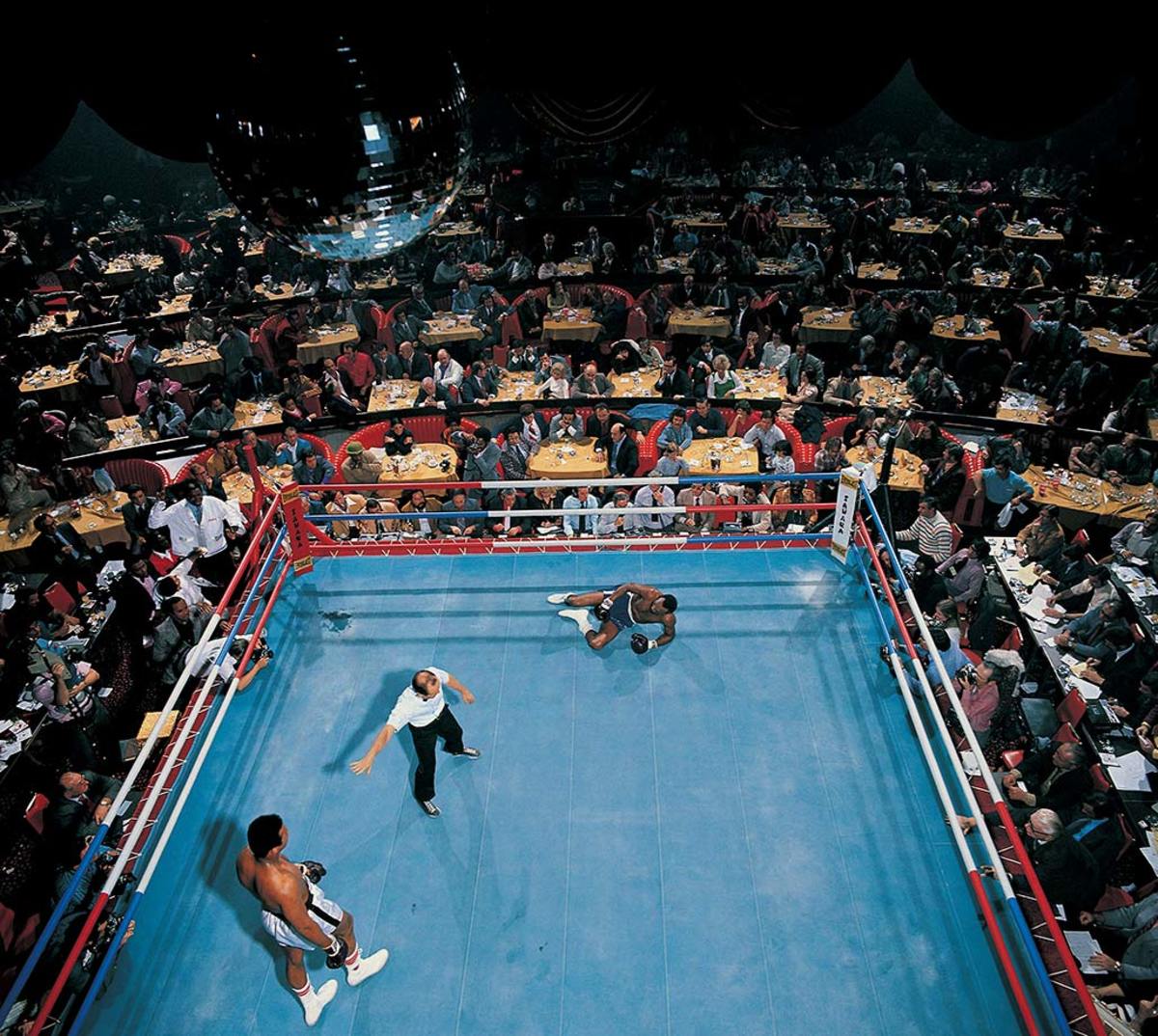

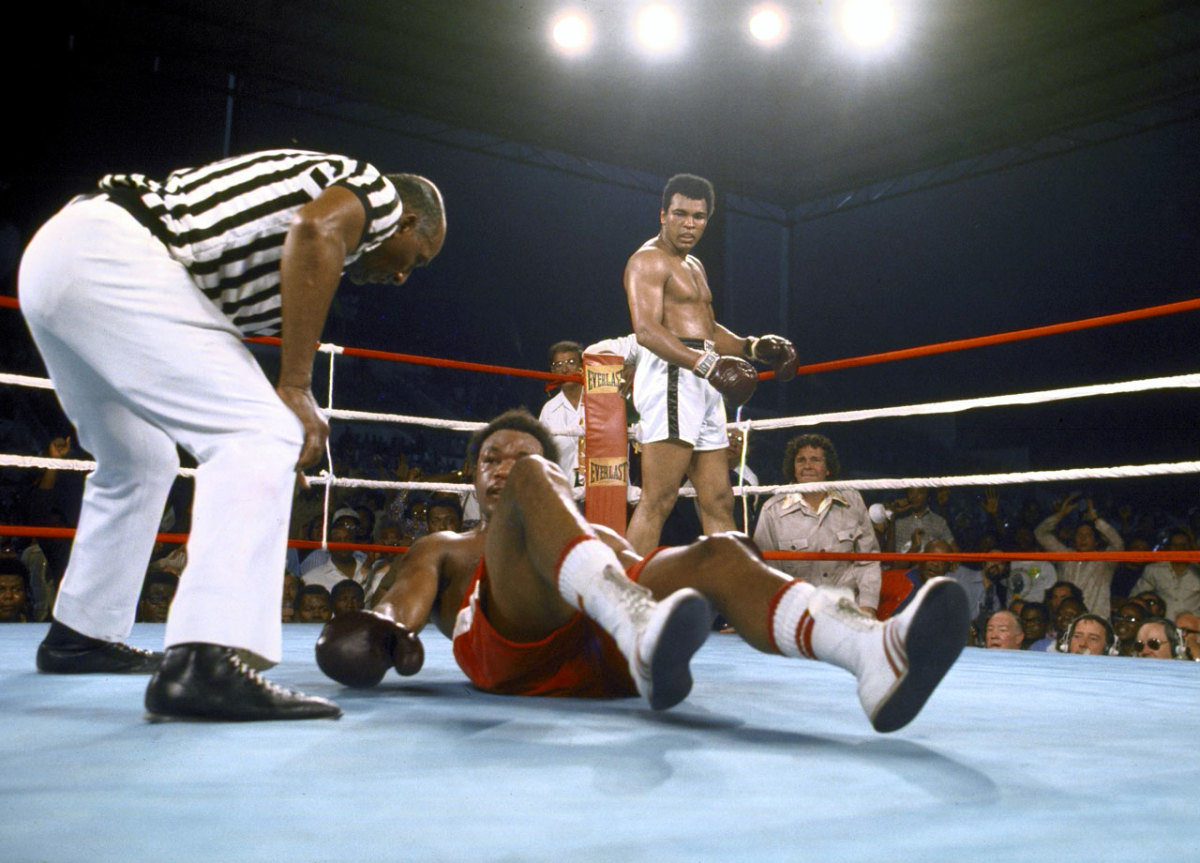

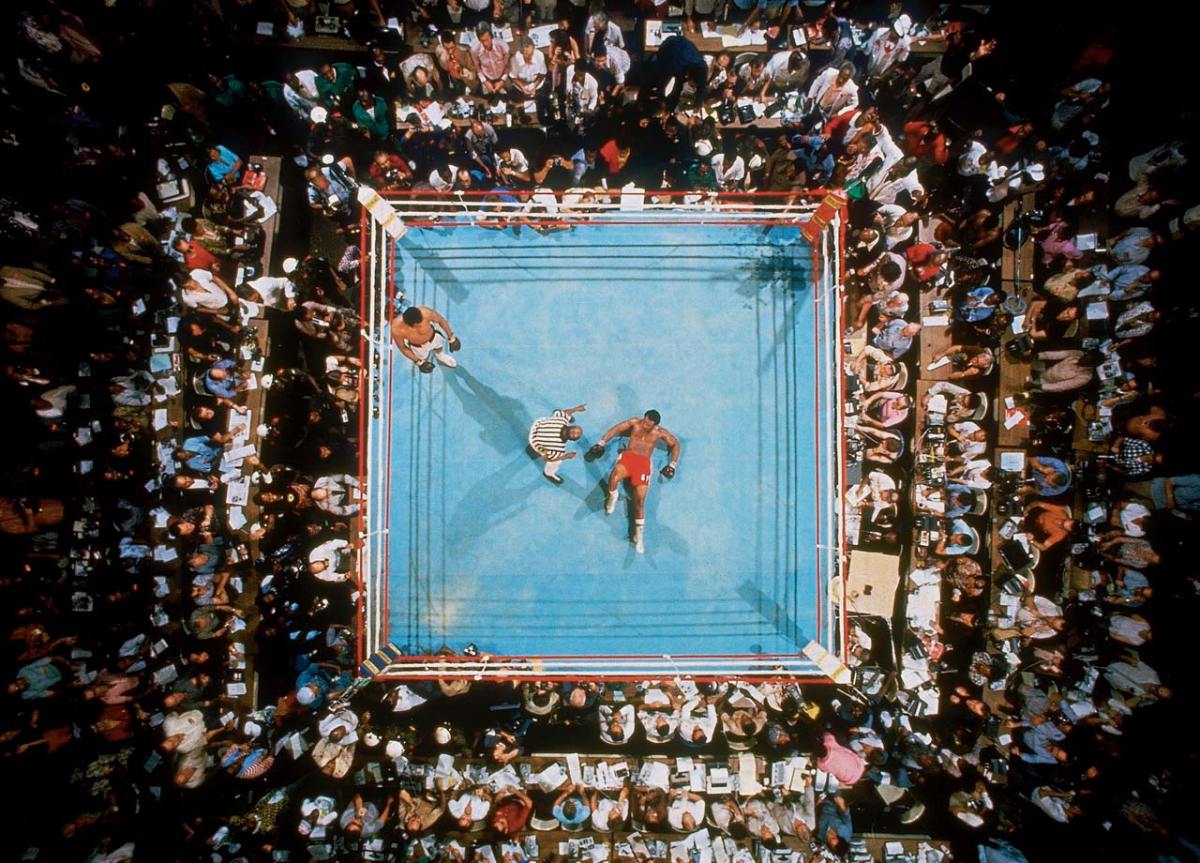

Foreman lies down on the canvas as Ali stands in the background during the Rumble in the Jungle. Ali knocked Foreman down with a five-punch combination in the eighth round, and referee Zack Clayton counted him out.

Big George stares at the ceiling as referee Zack Clayton counts him out in the eighth round. The victory made Ali, once again, the heavyweight champion of the world.

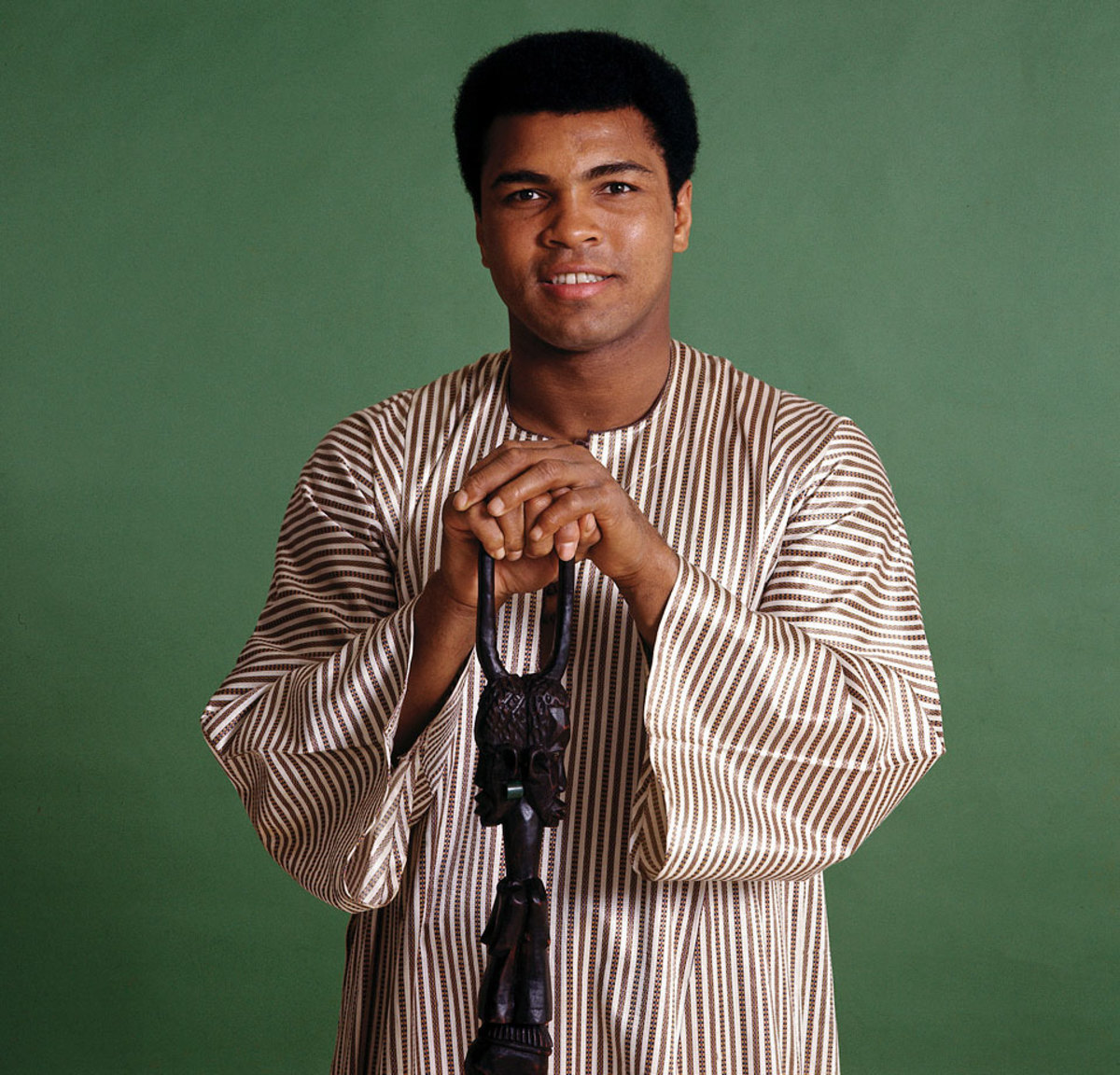

Ali poses for a portrait after being selected as the Sports Illustrated Sportsman of the Year in 1974. Ali wore a dashiki, a men's garment widely worn in West Africa. He also brought the walking stick given to him by Zaire's president.

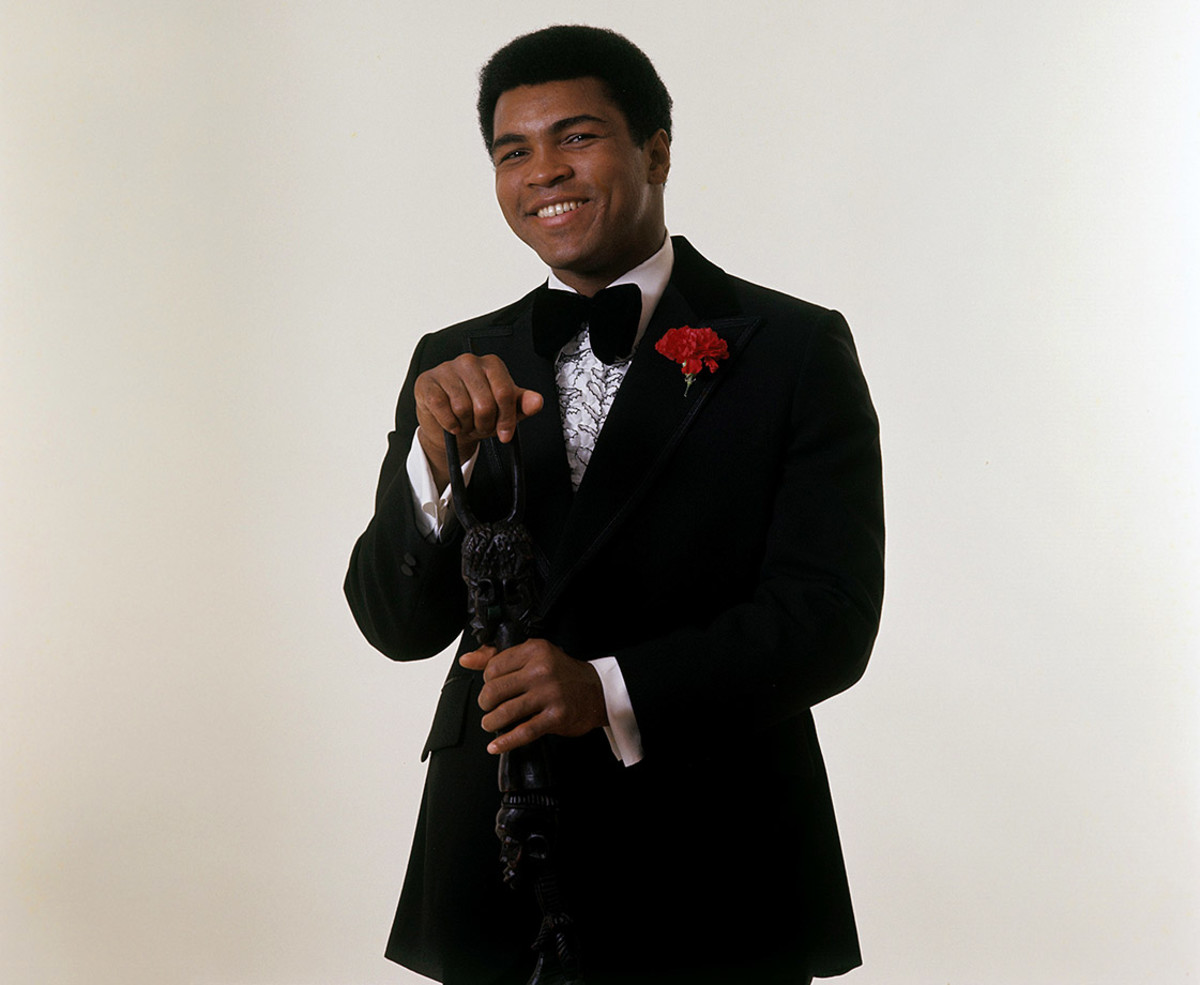

This time Ali wears a tuxedo, but keeps the walking stick, during the November photo shoot for Sports Illustrated's Sportsman of the Year.

Ali talks with Howard Cosell outside of the United Nations Headquarters for a segment on the Wide World of Sports. Later that day, Ali held a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

Ali talks with Reverend Jesse Jackson outside of the United Nations Headquarters before a press conference to announce that he would donate part of the proceeds from his fight against Chuck Wepner to help Africans in the Sahel drought.

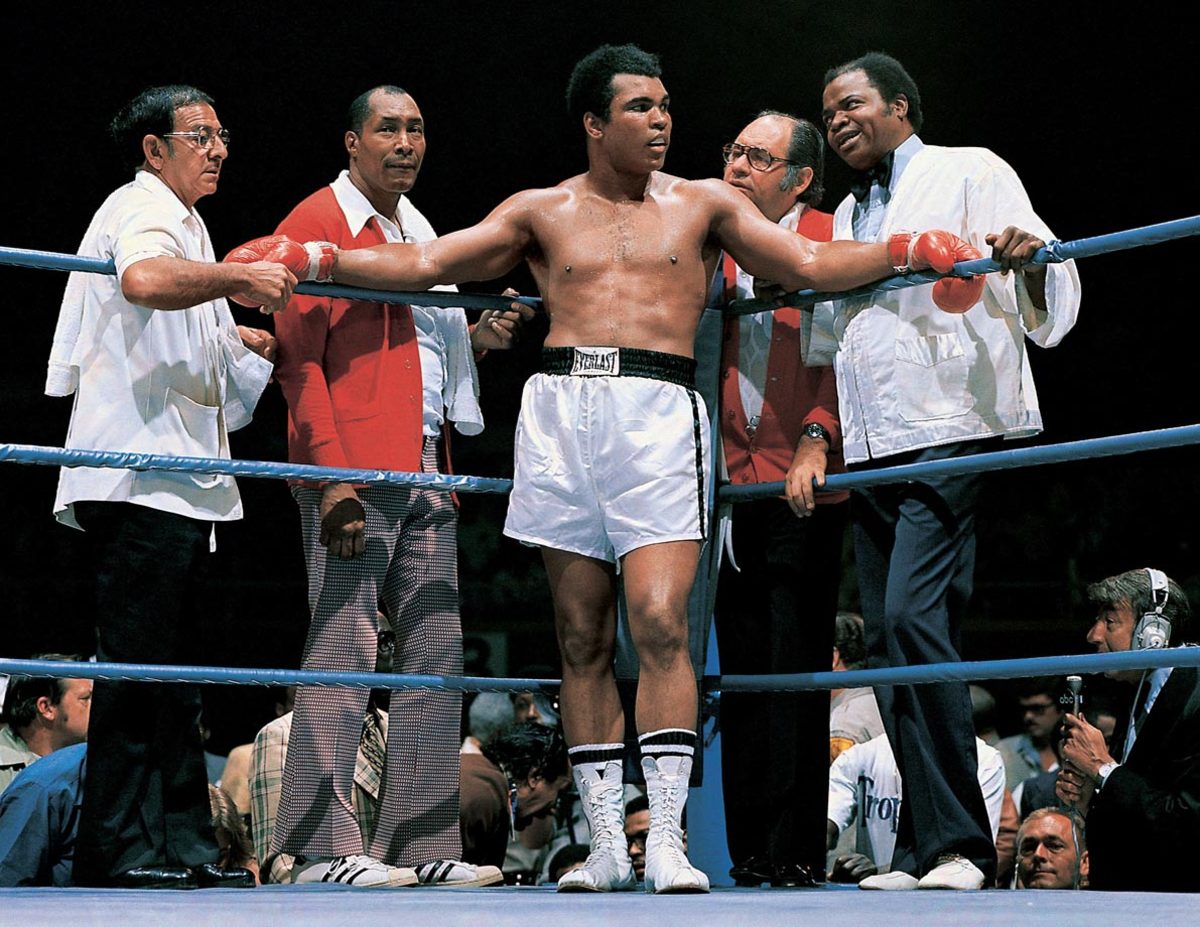

Ali stands with trainer Angelo Dundee, assistant trainer Wali Muhammad, physician Dr. Ferdie Pacheco and assistant trainer Drew Bundini Brown before his bout with Ron Lyle in May 1975. Ali won the fight by technical knockout in the 11th round.

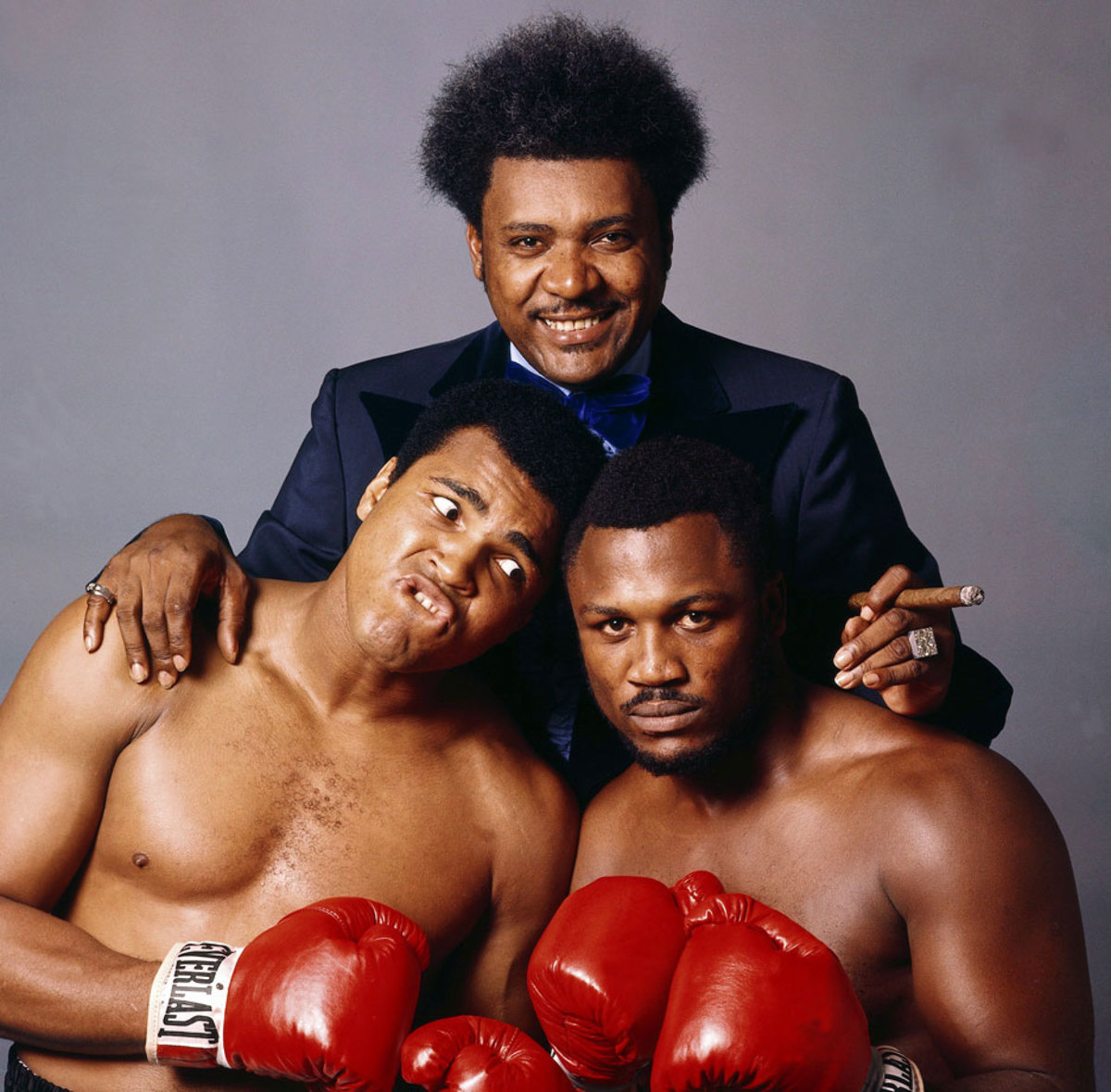

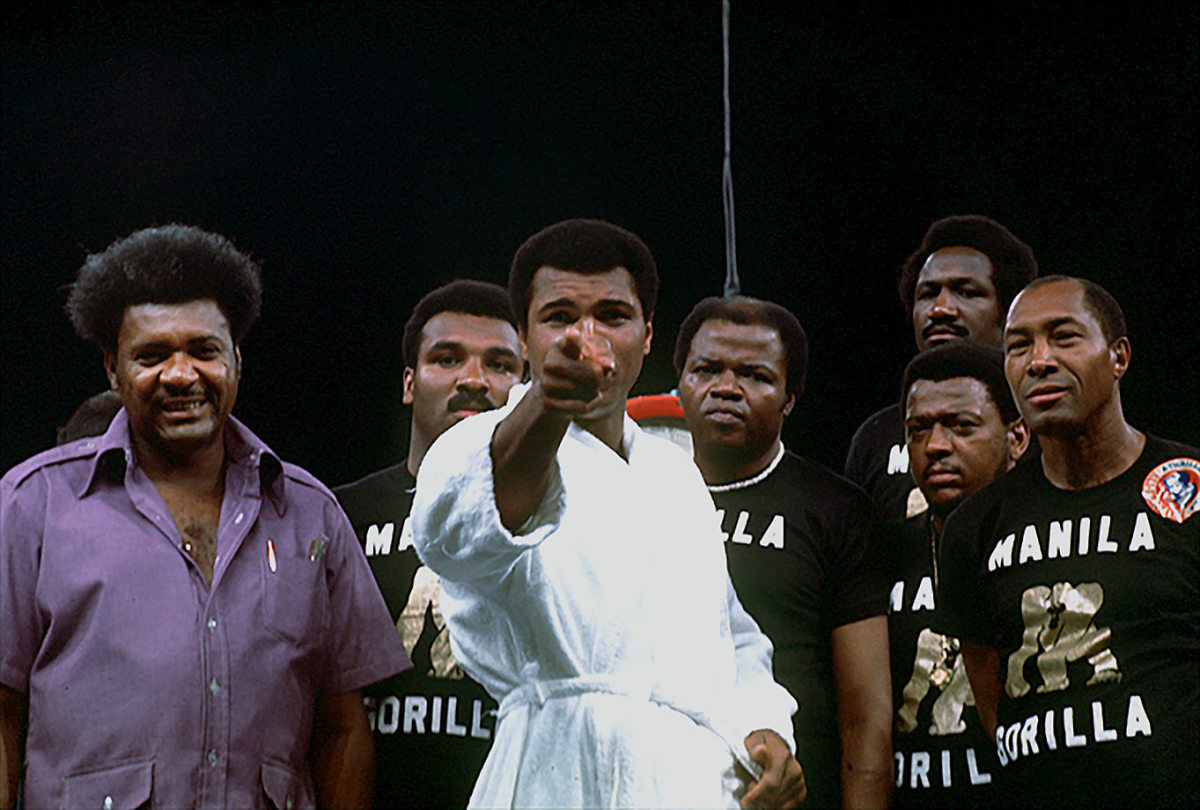

Along with Don King and Joe Frazier, Ali sat for a portrait leading up to the Thrilla in Manila. Ali verbally abused Frazier during the buildup to the fight, telling the media that "it will be a killa and a thrilla and a chilla when I get the gorilla in Manila."

Ali points at the camera with Don King and his training staff behind him before the weigh-in for the Thrilla in Manila in October 1975. Philippine president Ferdinand Marcos offered to sponsor the bout and hold it in Metro Manila to divert attention from the turmoil in the country that had forced the imposition of martial law in 1972.

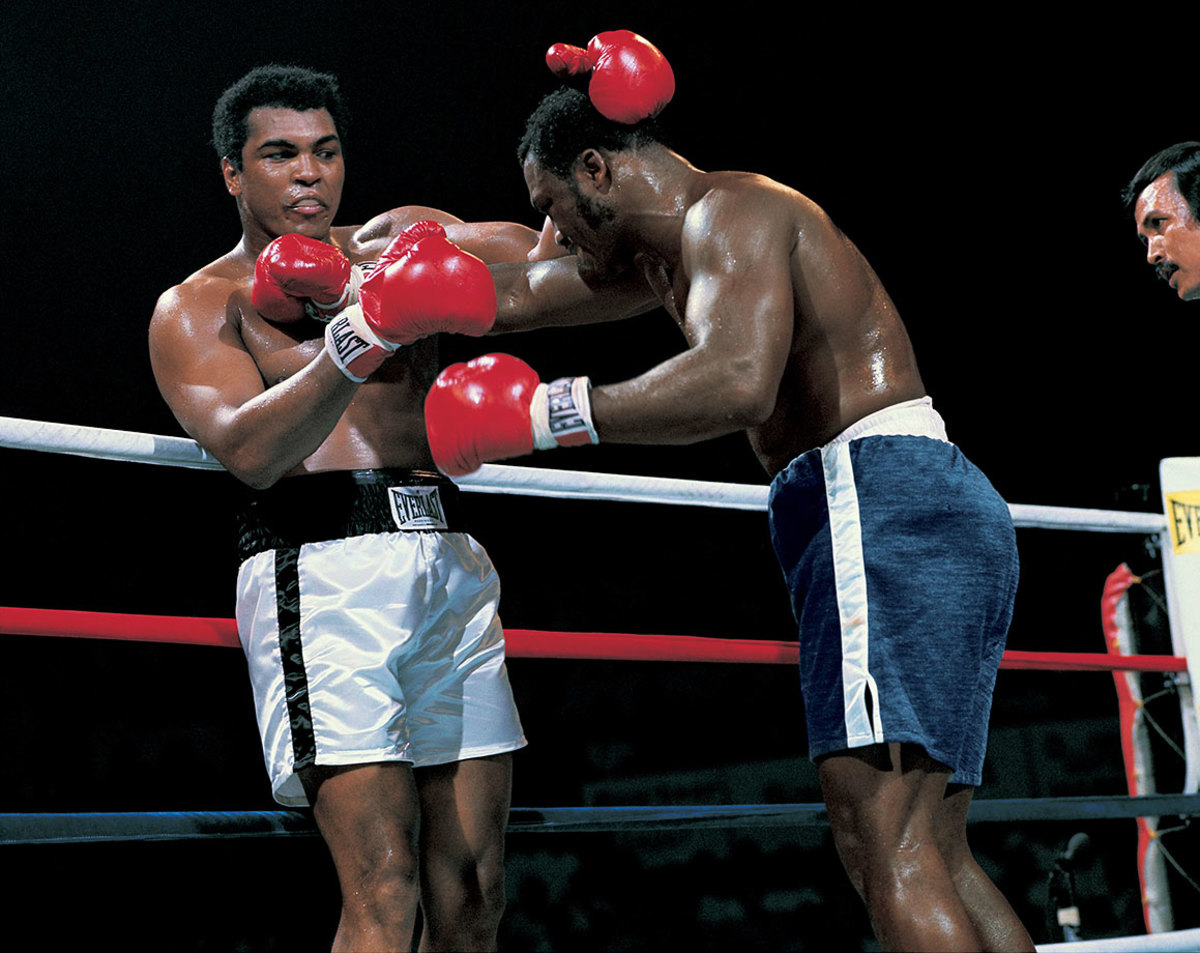

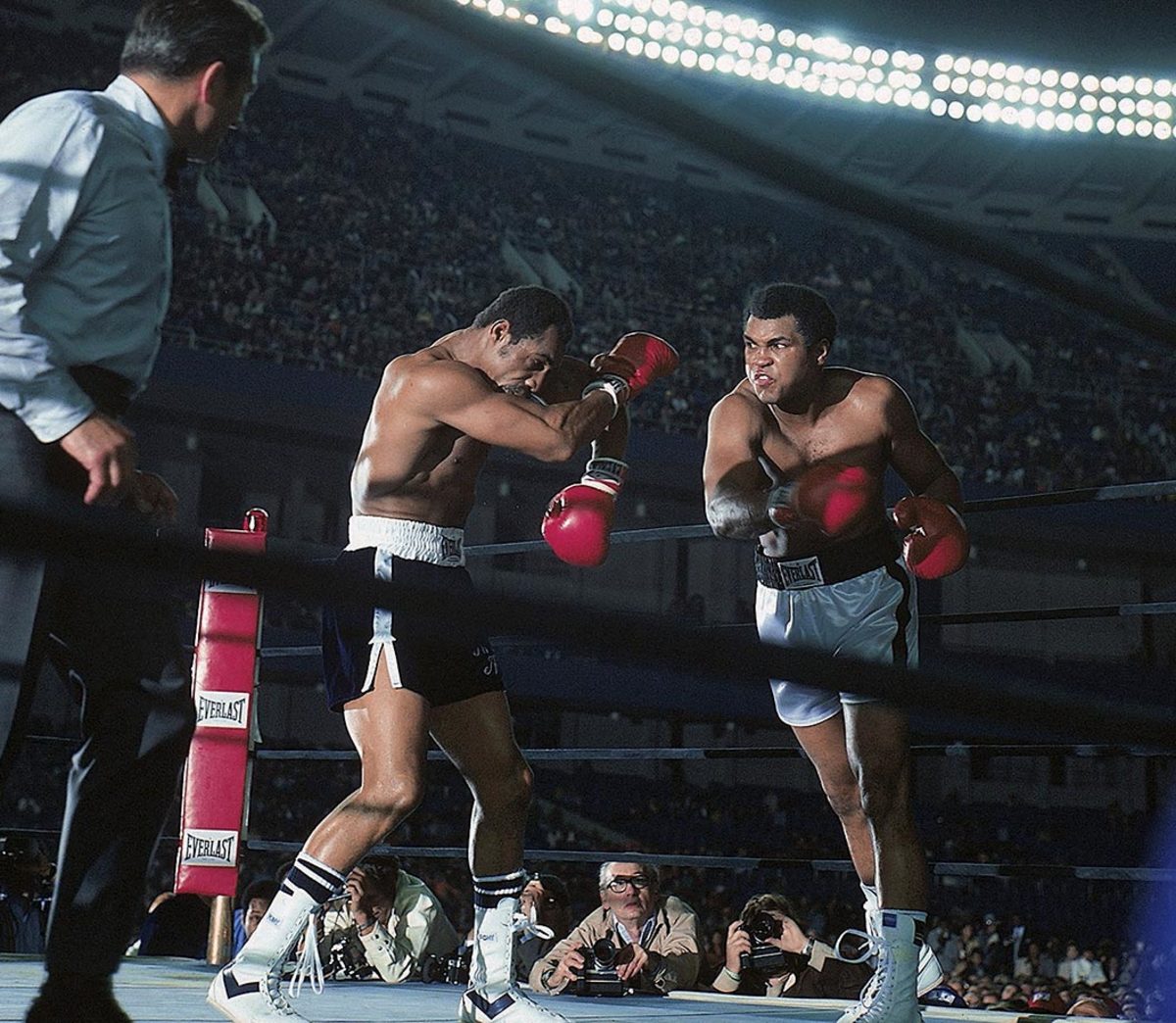

Wrapping up Joe Frazier proved more difficult than Ali expected, having thought Frazier would represent an easy payday and be unable to live up to his billing. The fight turned out to be a brutal affair.

Frazier faces an Ali right hook in their fight in Quezon City, Philippines. The two fighters traded vicious blows during their 14 rounds. "Man, I hit him with punches that'd bring down the walls of a city," Frazier said. Ali withstood the blows to win by TKO in the 15th round.

The third fight between Ali and Frazier, Ali won the bruising battle between the two powerful punching heavyweights when Frazier's trainer, Eddie Futch, stopped the fight before the 15th round.

A back and forth exchange, Ali controlled the early rounds of the Thrilla in Manila before Frazier fought back with powerful hooks. Ali finished strong, regaining momentum in the later rounds.

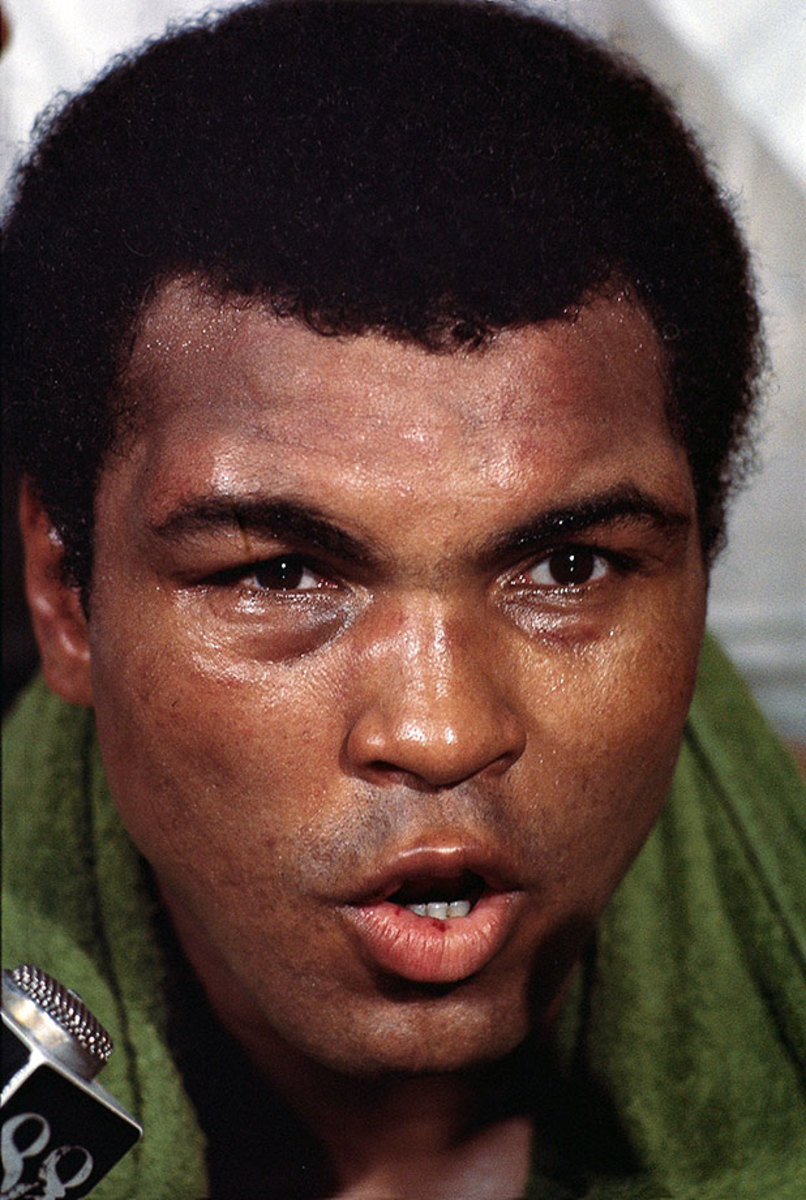

Ali speaks to the press after winning the Thrilla in Manila bout with Frazier.

Ali holds a drinking concoction given to him by Dick Gregory, an advocate of a raw fruit and vegetable diet, in 1976.

Before his 1976 fight against Ken Norton at Yankee Stadium, Ali watches a fight on television from his hotel room. A police strike at the time of the fight created a dangerous environment outside the stadium that all but eliminated walk-up sales.

Norton takes a right hook during the heavyweight title fight against Ali. The bout, which Ali won by a unanimous, but controversial, decision, was the last boxing match at Yankee Stadium until 2010.

Ali makes a face during his fight with Earnie Shavers in 1977 at Madison Square Garden. Hurt badly by Shavers in the second round, Ali rebounded and outboxed Shavers throughout to build a lead on points before Shavers came on again in the later rounds. Seemingly exhausted going into the 15th and final round, Ali remained victorious by producing a closing flurry that left Shavers wobbling at the bell and the Garden crowd once again in delirium over his Ali magic.

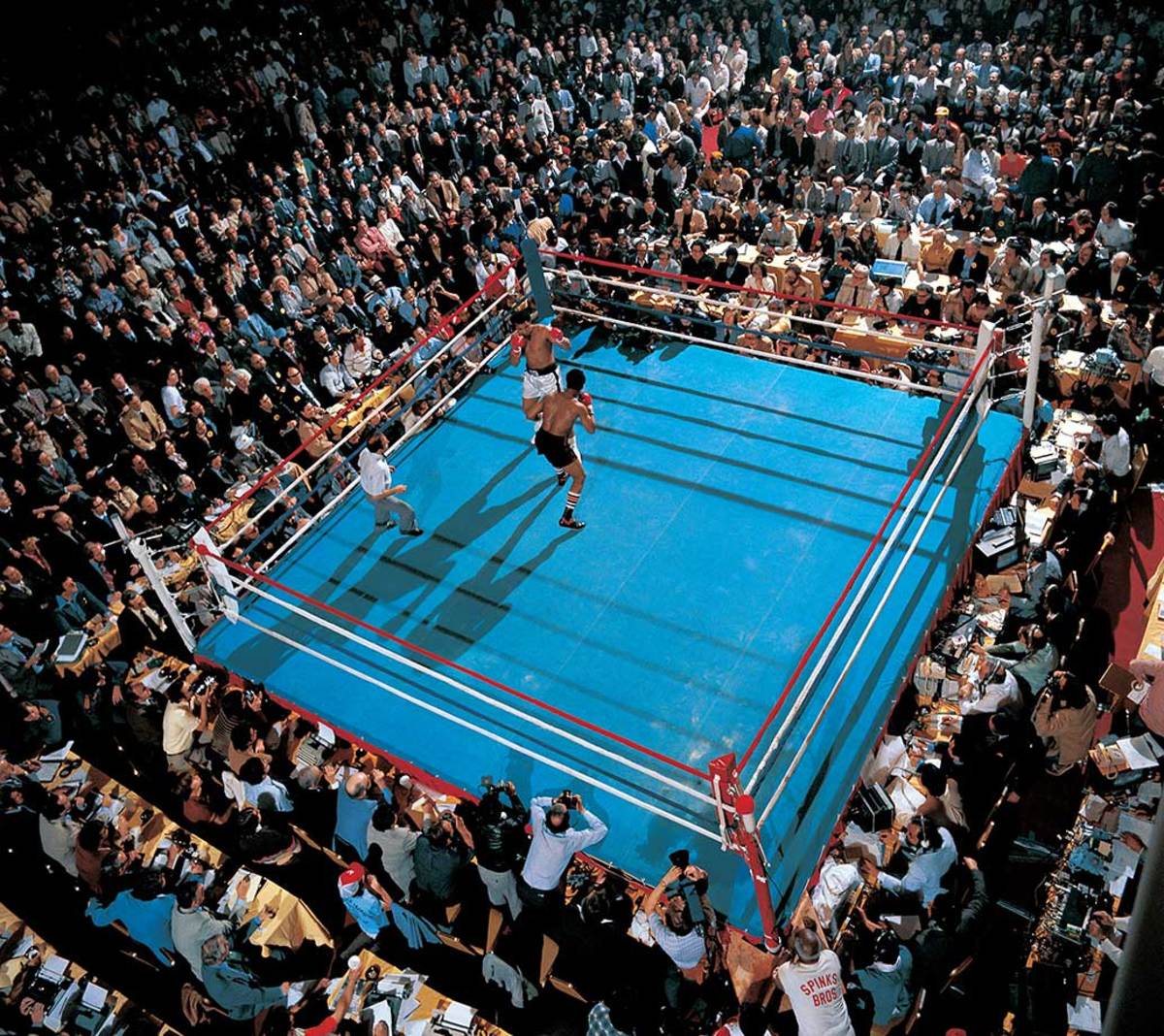

Ali squares off with Leon Spinks at the Las Vegas Hilton Hotel in February 1978. Spinks won the fight in a split decision, ending Ali's 3.5-year reign as the heavyweight champion. It was the only time in Ali's career that he lost his championship title in the ring.

Leon Spinks took center stage over Ali at the press conference after their fight. The victorious Spinks and his gap-toothed grin were featured on the Feb. 19, 1978 cover of Sports Illustrated.

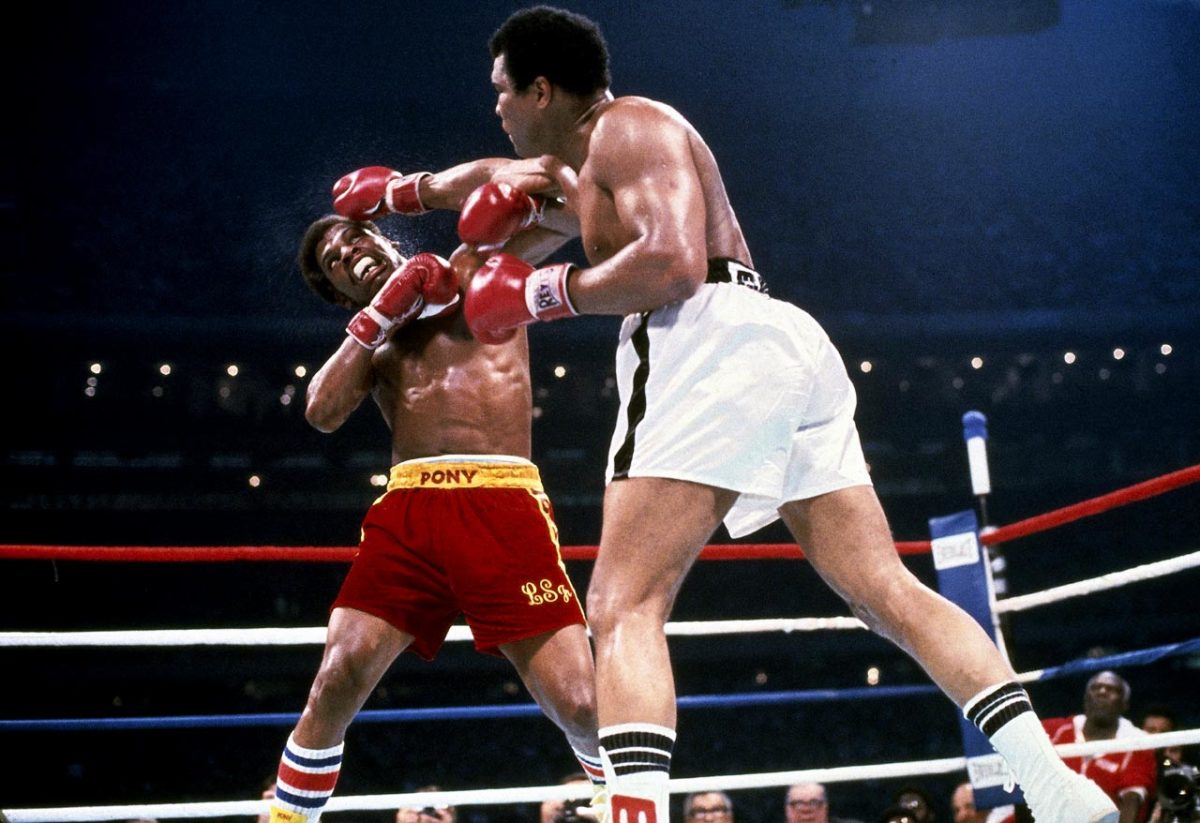

Ali lands a straight right hand to the head of Spinks in the rematch of their title bout in 1978. Ali won on a 15 round decision.

Don King pulled the strings again when Ali faced Larry Holmes before their November 1980 fight. King became a key figure in Ali's career, promoting his biggest fights, the Thrilla in Manila and the Rumble in the Jungle.

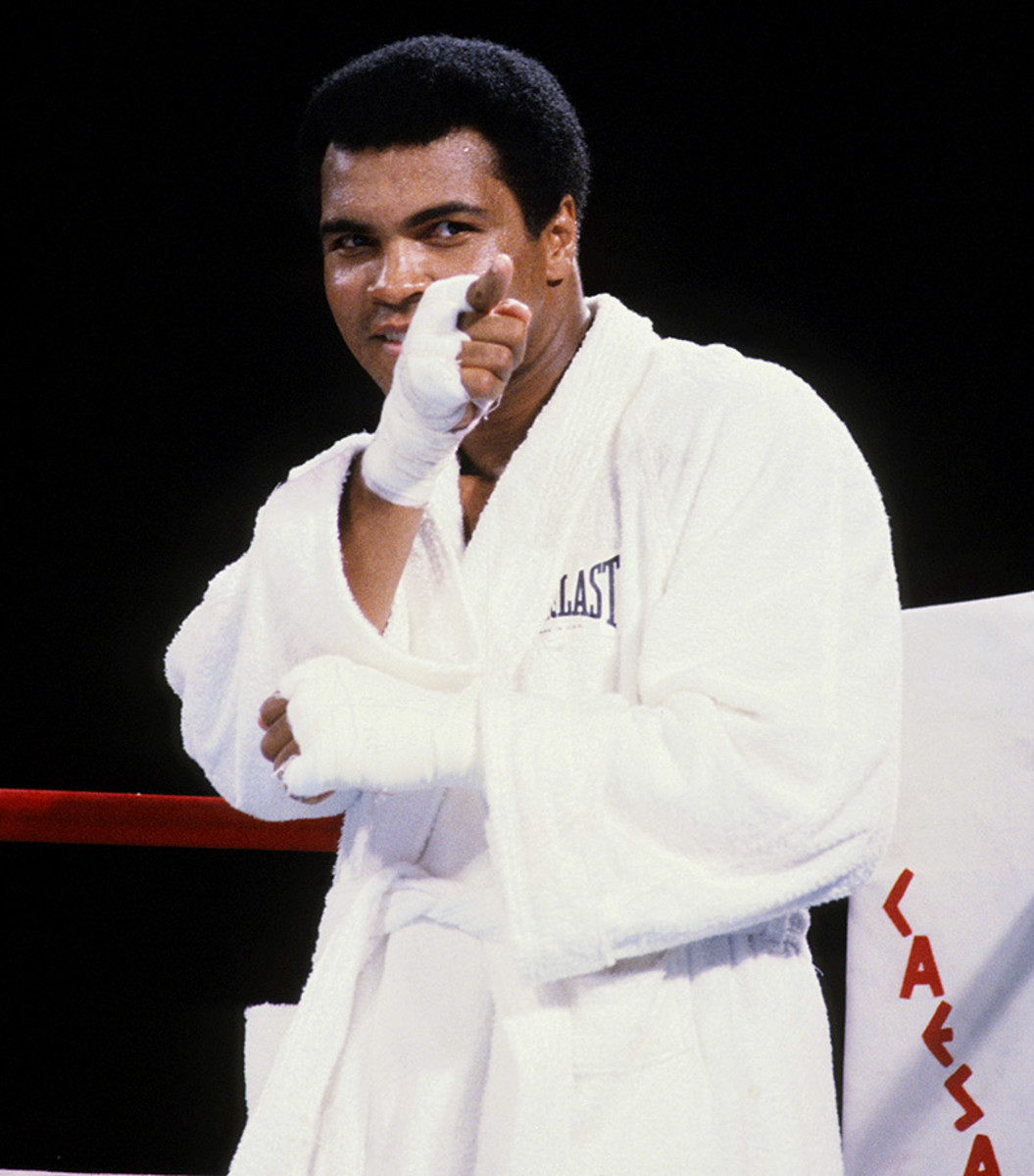

Ali points at Larry Holmes before their bout at Caesars Palace in 1980.

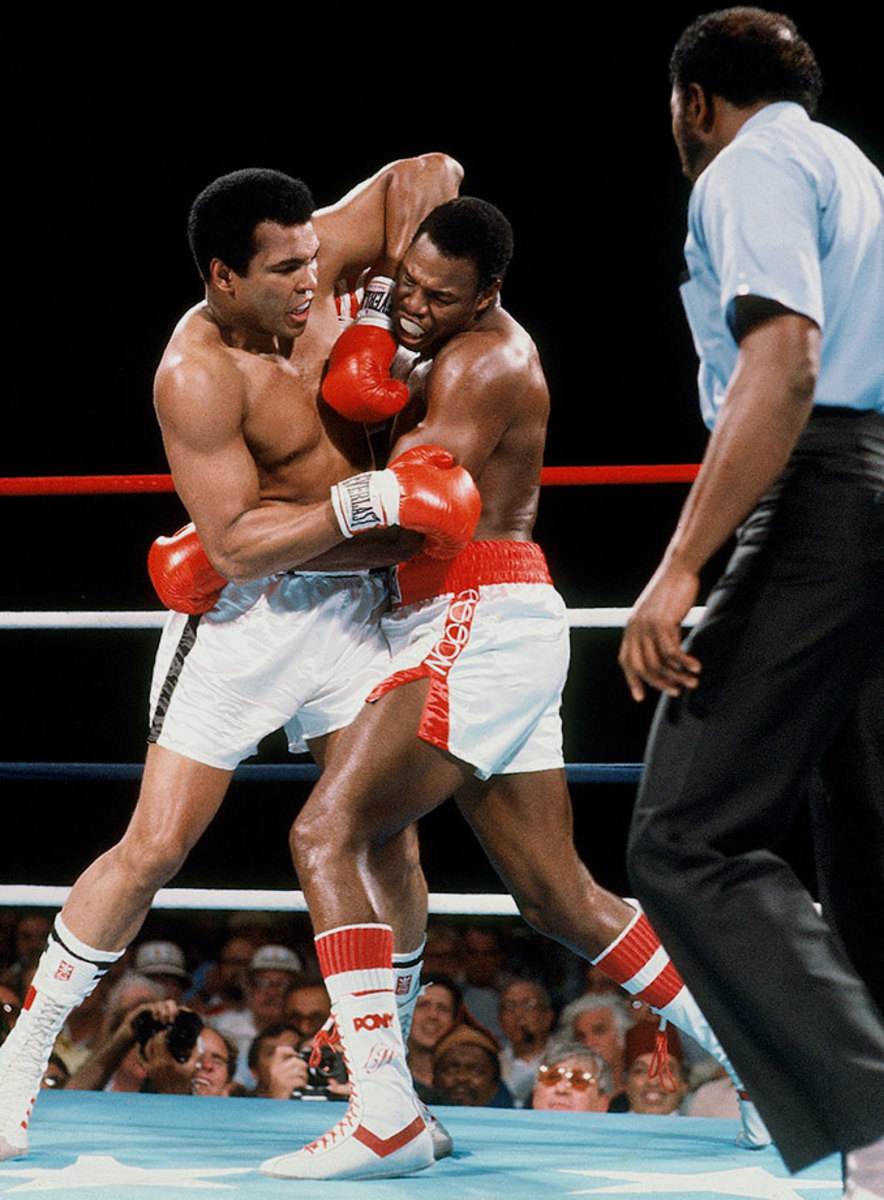

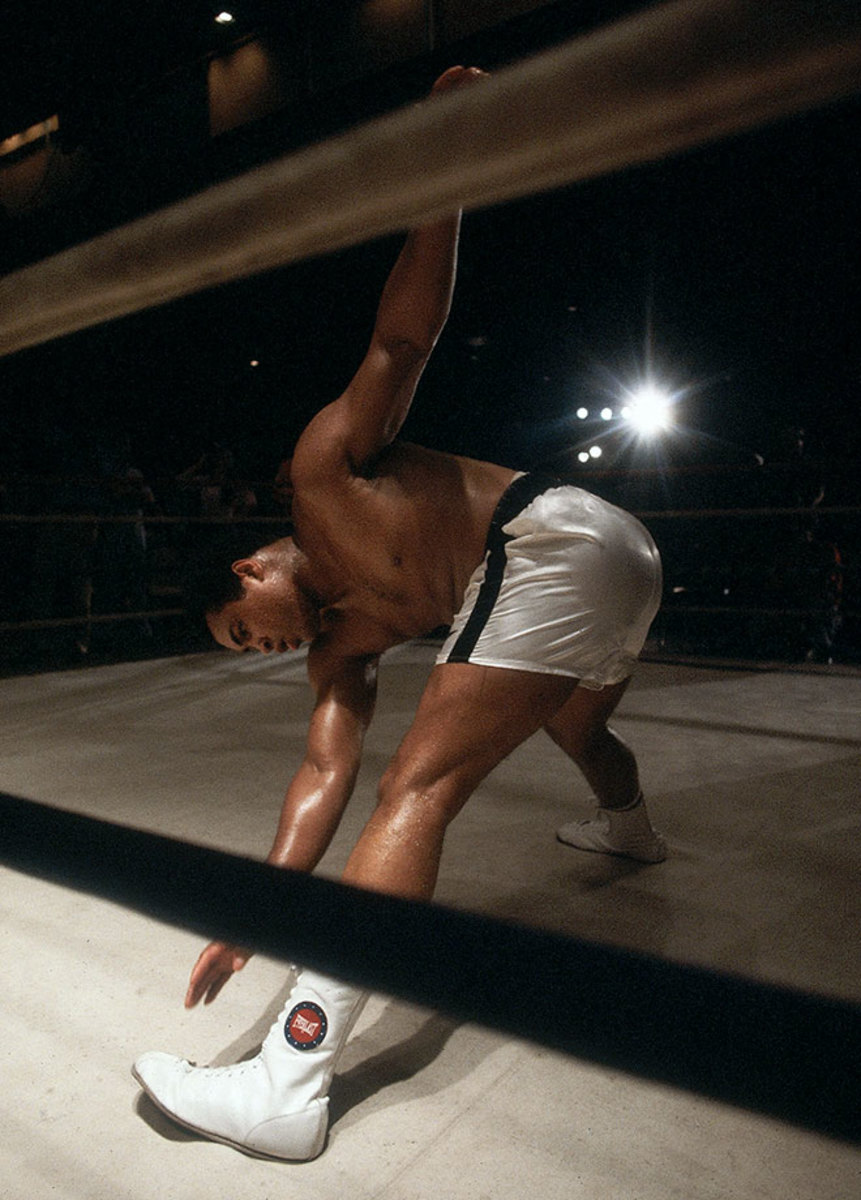

Ali grapples with Holmes during their bout in 1980. Trainer Angelo Dundee stopped the fight in the 11th round, marking the fight as Ali's only career loss by knockout.

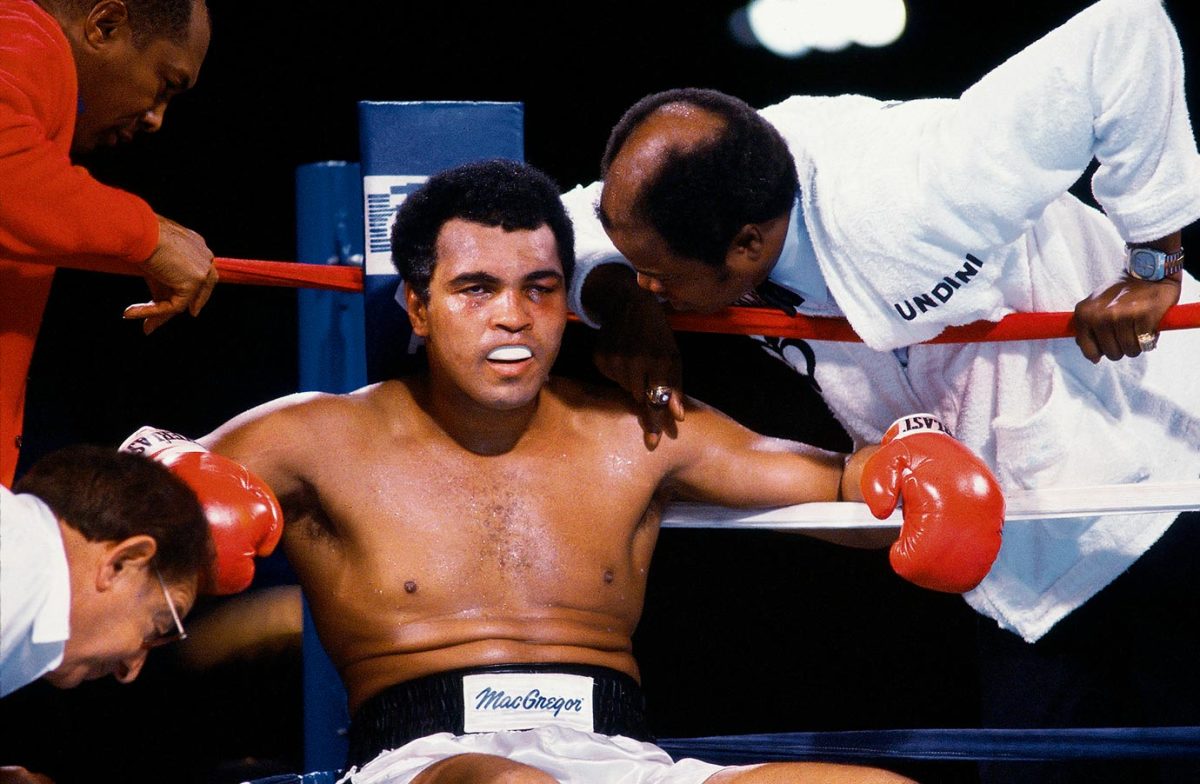

Drew Bundini Brown leans in to speak to Ali, who returned to fight Holmes after a brief retirement. By this time, Ali had already begun developing a vocal stutter and trembling hands and taken thyroid medication to lose weight that left him tired and short of breath.

Ignoring pleas for his retirement, Ali stretches before a fight against Trevor Berbick in Nassau, Bahamas. Ali lost to Berbick in a unanimous decision and retired after the bout, the 61st of his career.

Ali pretends to spar with artist LeRoy Neiman at his home in Los Angeles. Neiman met Ali in 1962 and made many paintings and sketches from throughout Ali's life.

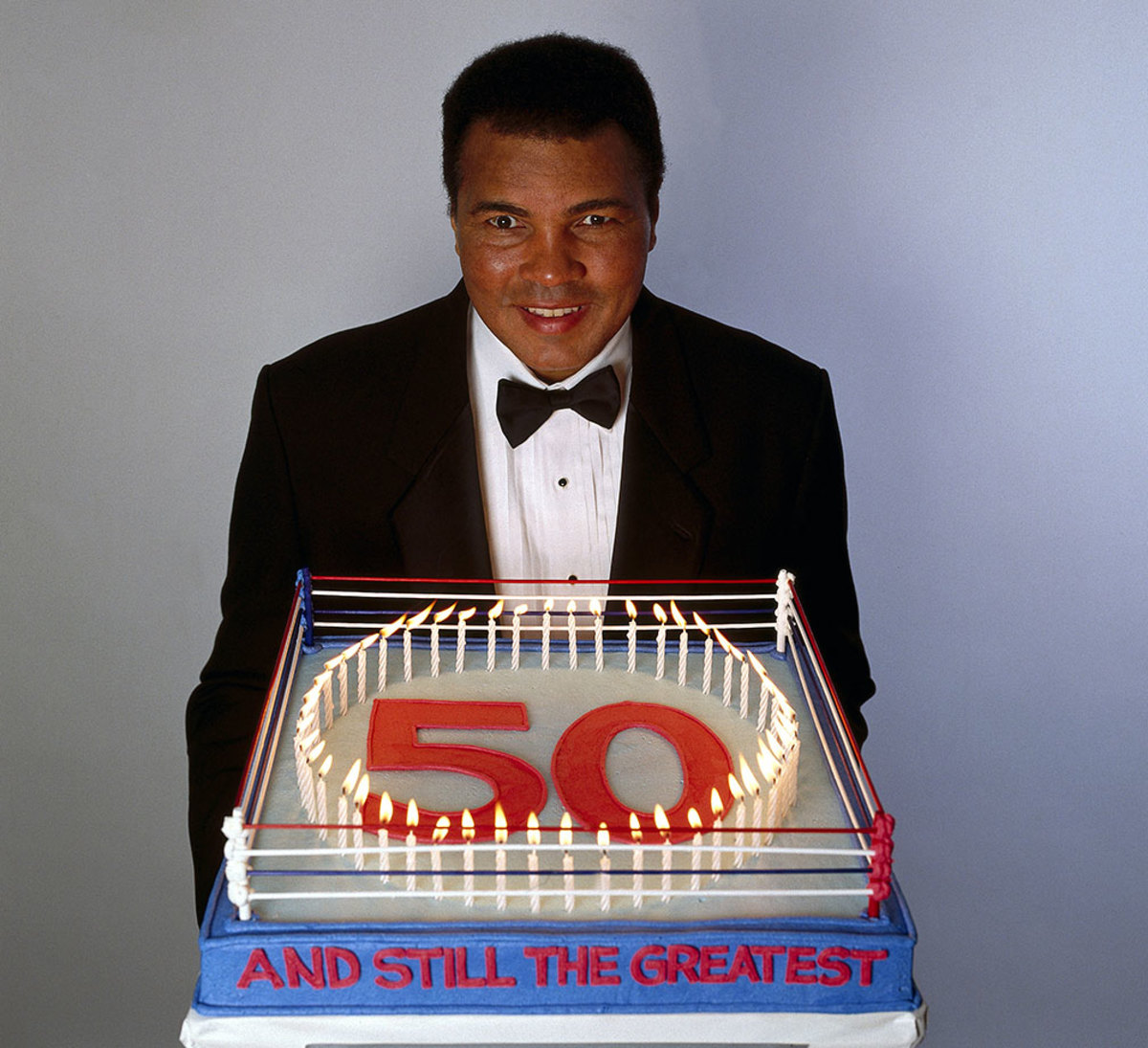

Cake in hand, Ali poses for a 50th birthday portrait in 1991. Although diagnosed with Parkinson's syndrome seven years earlier, Ali was still active, traveling to Iraq during the Gulf War to meet with Saddam Hussein in an attempt to negotiate the release of American hostages.

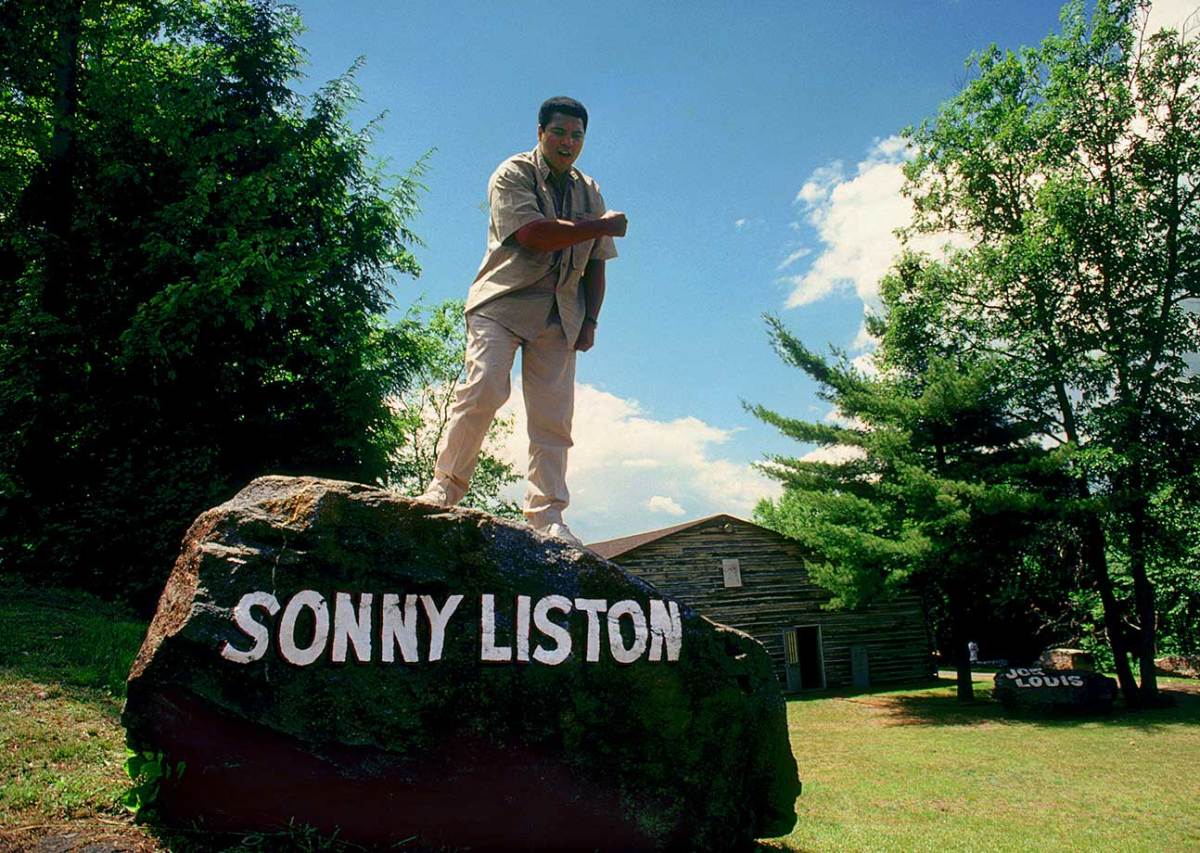

The same year, Ali stands atop of the Sonny Liston rock at his old training camp cabin. Ali and his father painted the names of famous boxers he admired on 18 boulders at the camp.

Ali carries the Olympic torch inside Centennial Olympic Stadium at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics. Despite trembling hands, Ali had the honor to light the Olympic flame in the stadium.

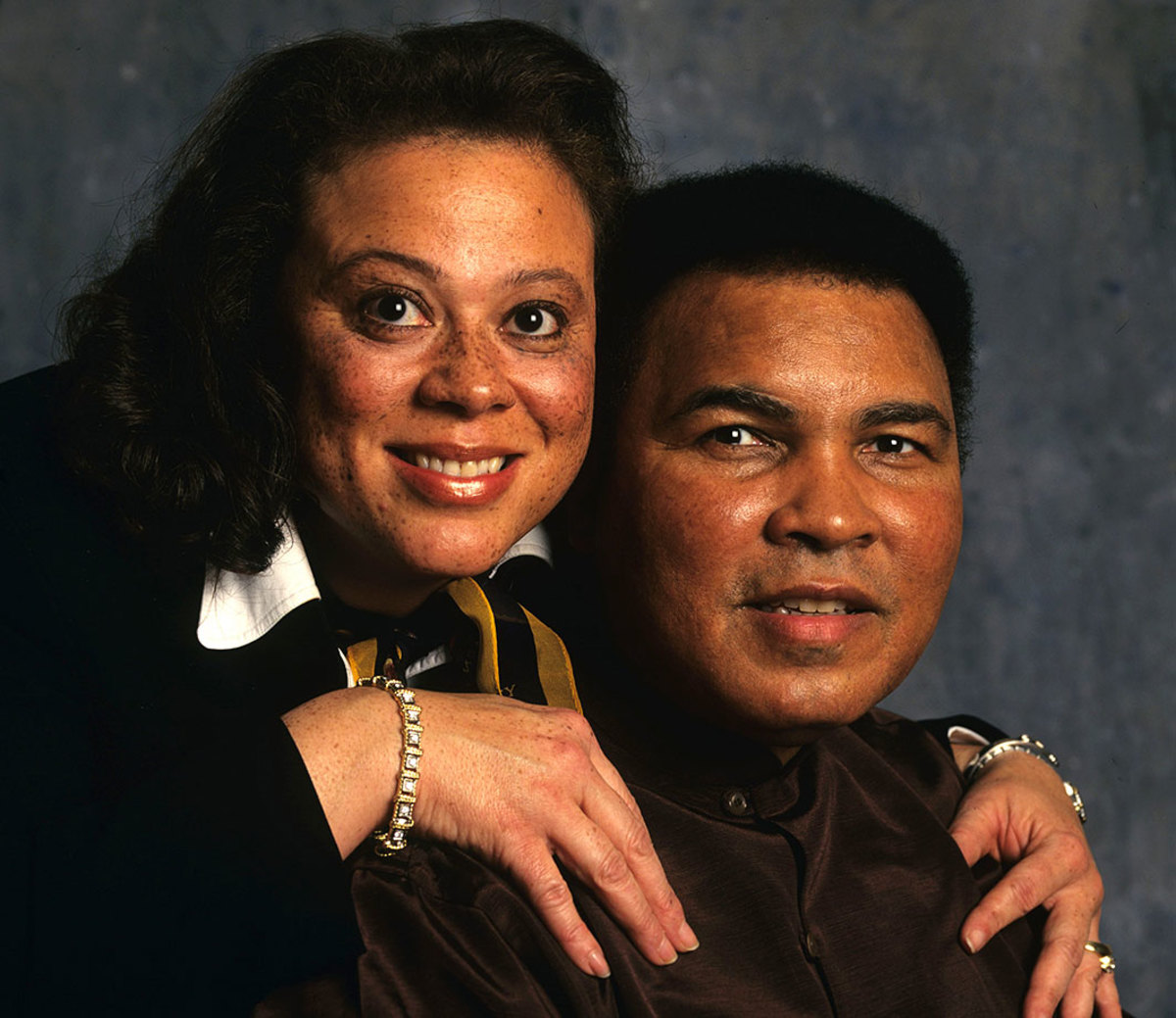

Husband and wife pose for a portrait during a photo shoot in 1997. Muhammad and Lonnie married in 1986 and have an adopted son together, Asaad Amin Ali.

Ali messes around with actor Billy Crystal during a photo shoot in 2000. Crystal's impression of Ali was notorious, and he performed at a tribute to the boxer on his 50th birthday in December 1991.

Ali lies on the canvas as his son, Assad Amin Ali, stands over him invoking memories of Ali's victory over Sonny Liston during a photo shoot in the gym at his farm on Kephart Road near Berrien Springs in 2001.

Fierce rivals in the ring, Ali and Joe Frazier pose for a portrait in the boxing robes they wore the night of their first bout at Frazier's Gym in 2003. Ali said after Frazier's death in 2011 that he was "a great champion."

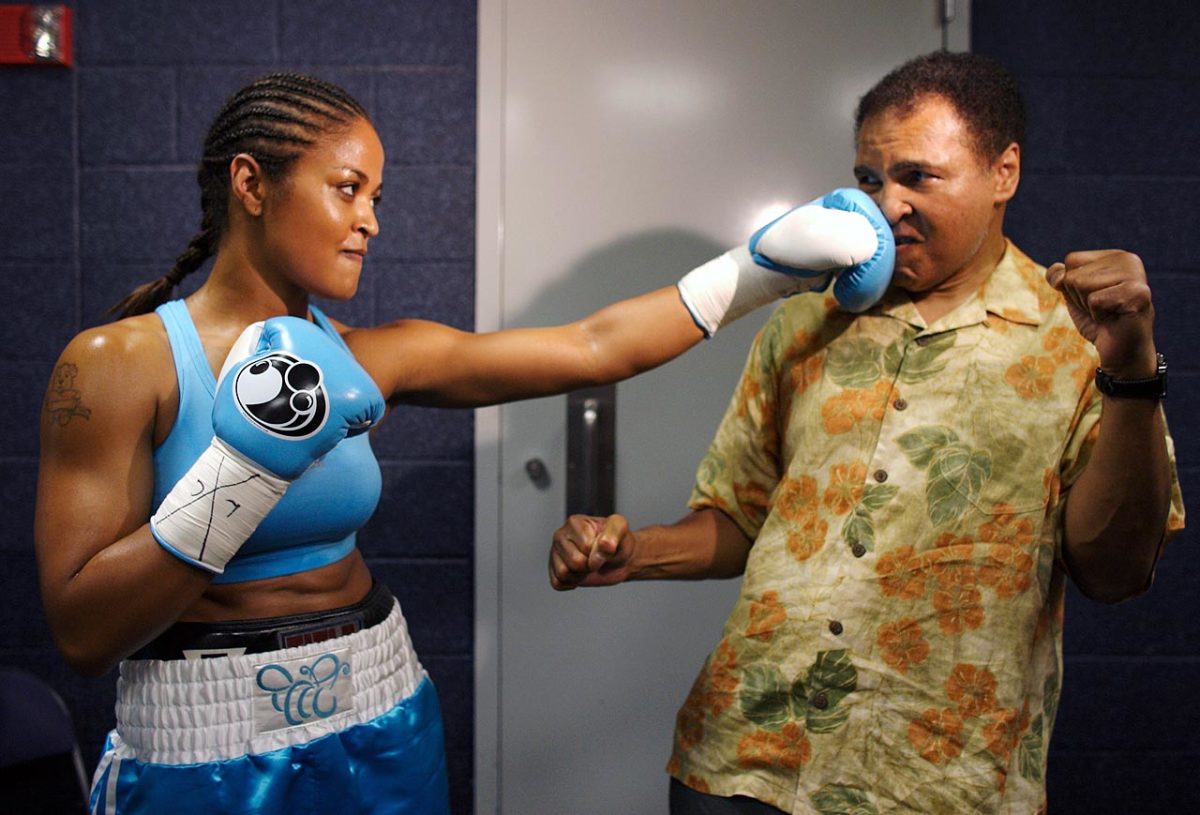

Ali takes a punch from his daughter Laila Ali while sparring before her fight against Erin Toughill in 2005. Laila retired from her own successful boxing career with a professional record of 24-0.

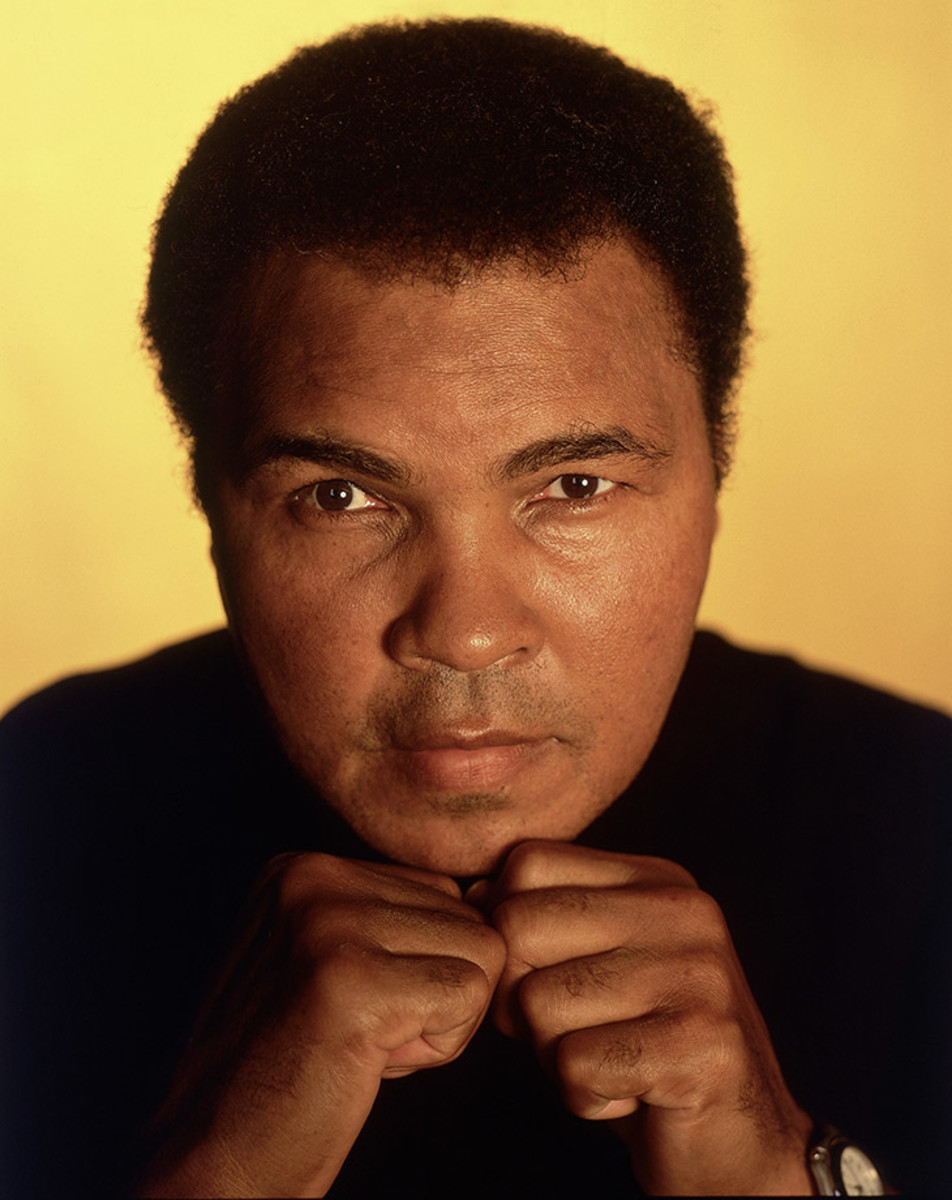

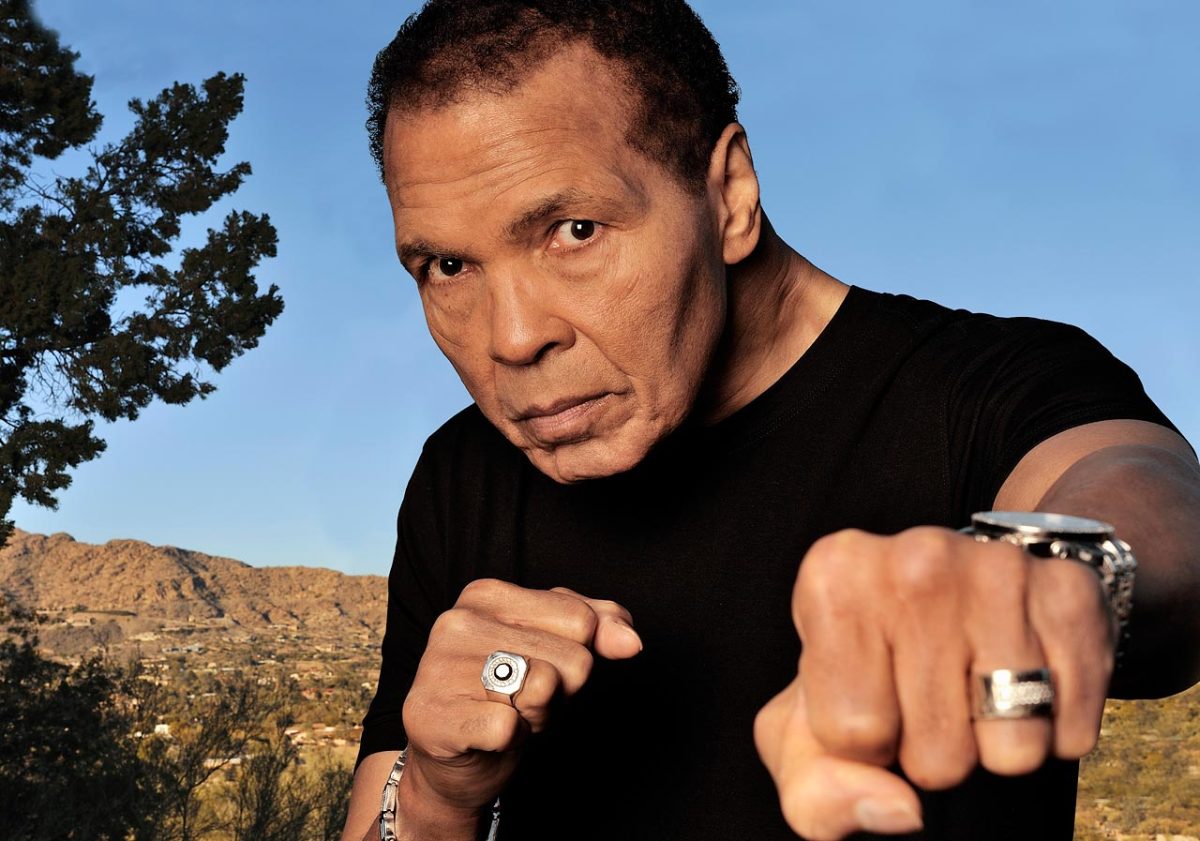

Ali poses with his fists up for a portrait in 2005.

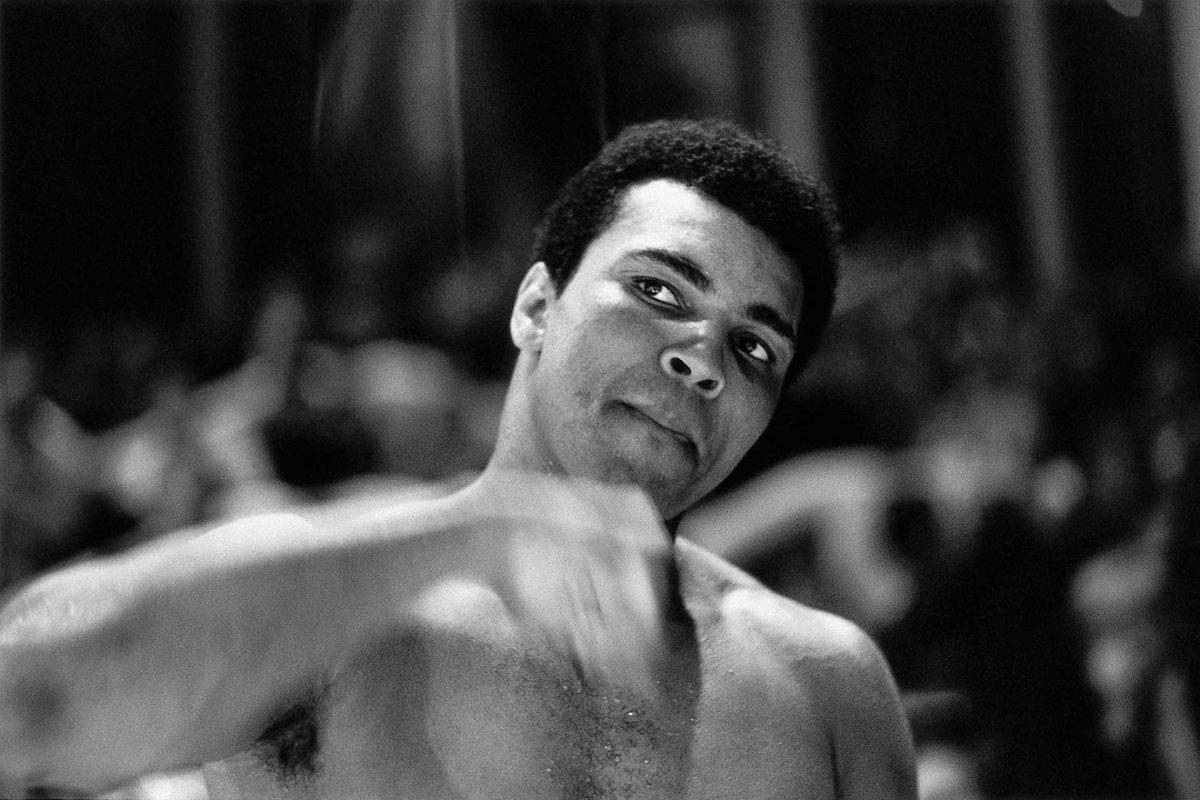

Ali poses with an extended punch in a 2012 photo shoot at his home in Paradise Valley, Ariz., to mark his 70th birthday.

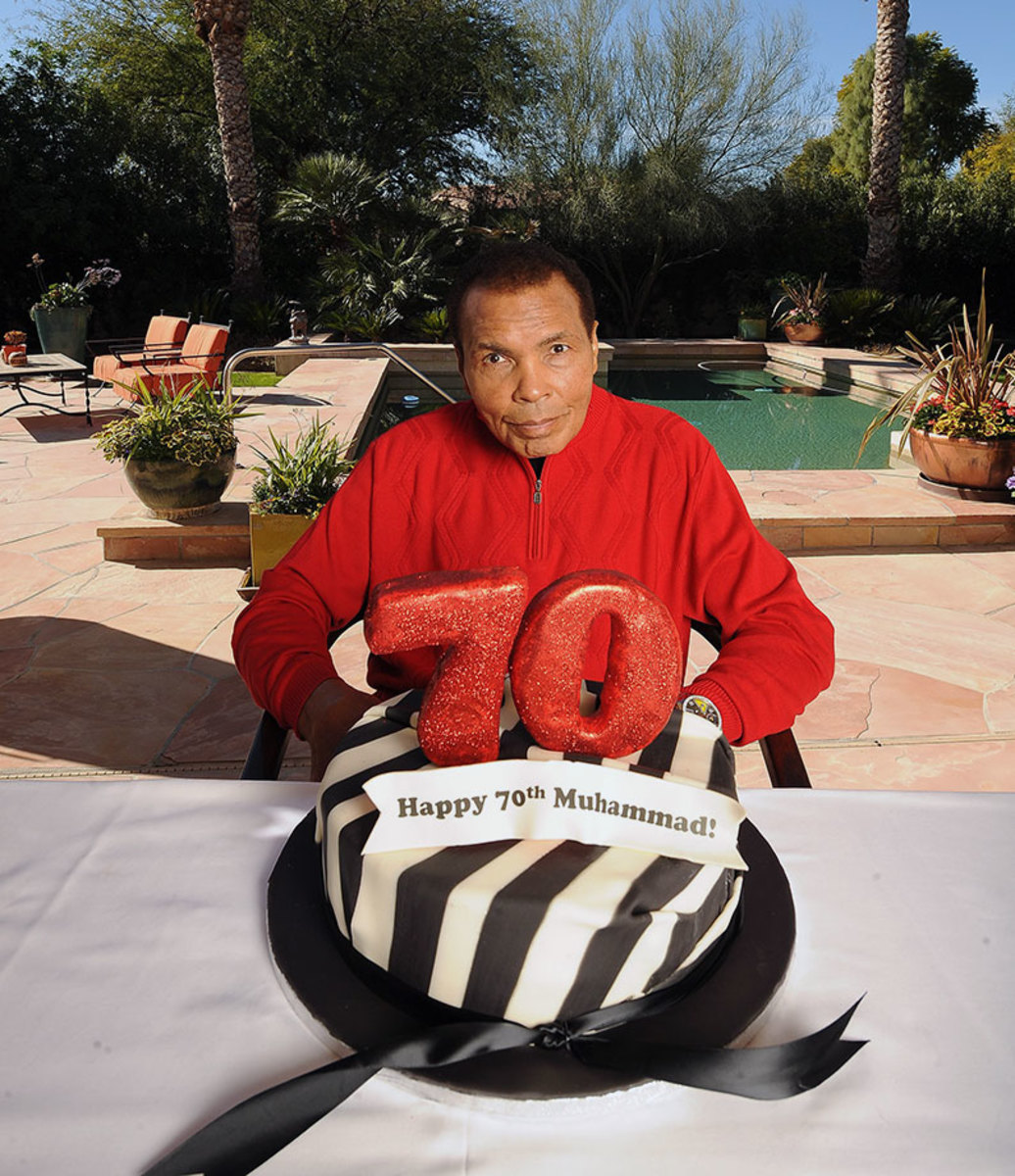

Ali sits in front of a 70th birthday cake in January 2012 at his Arizona home. Later that year he appeared at the opening ceremonies for the 2012 Olympics in London to escort the Olympic flag into the stadium, 52 years after he won gold in Rome.