One more time to the top

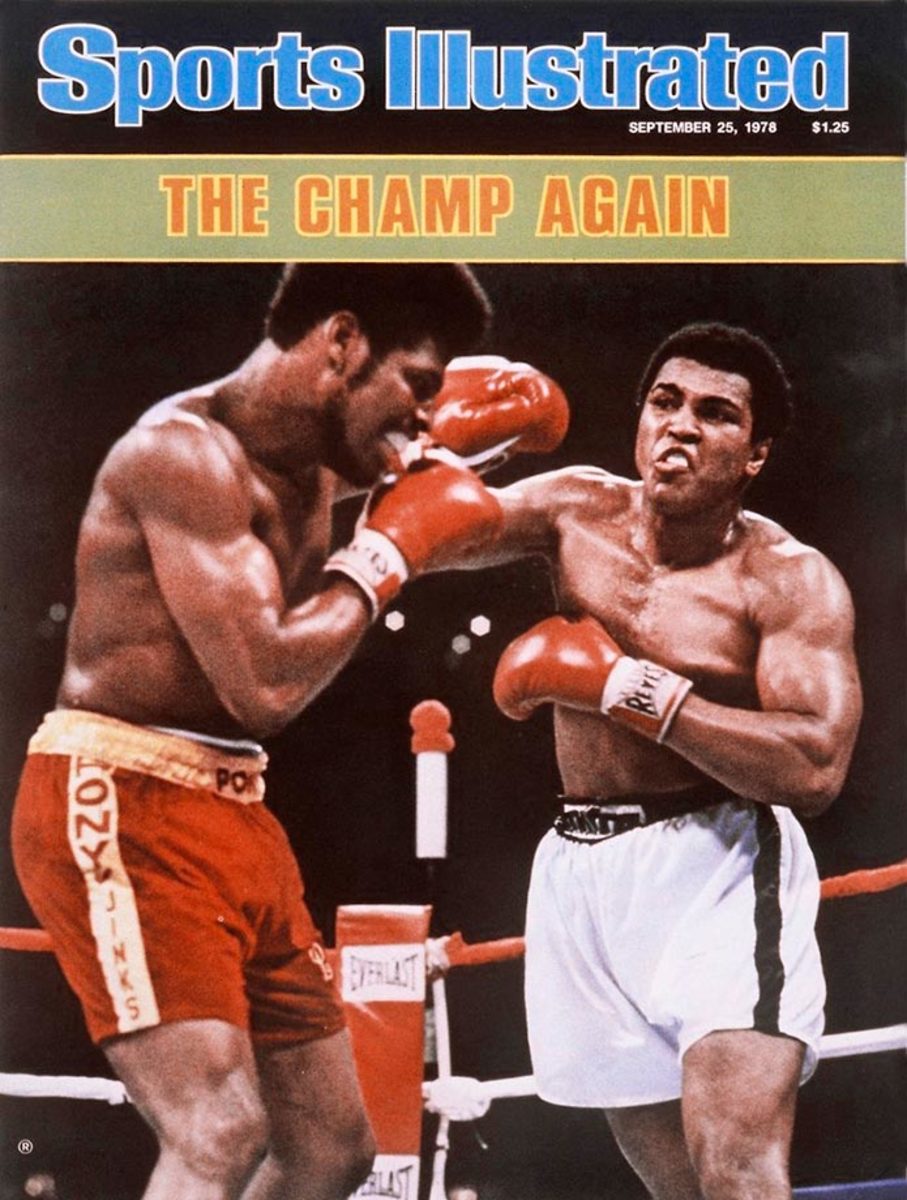

This story originally appeared in the Sept. 25, 1978 issue of Sports Illustrated. Subscribe to the magazine here.

This was not the old Muhammad Ali, not by a half. But last Friday night in the New Orleans Superdome, driven by an ambition as vaulting as the structure, Ali dominated without letup a badly confused Leon Spinks. And after 15 perpetual-motion rounds, Ali had won the world heavyweight championship for an unprecedented third time. The decision was unanimous and indisputable.

As a fight it was not so much a contest as it was a demonstration by an old master educating an inexperienced youngster in the fine points of the craft. But at 36, Ali teaches a better game than he plays. The result was that, as a whole, the fight was sloppy.

“Sloppy?” howled a happy Angelo Dundee, the trainer who had plotted Ali’s battle plan. “It was beautifully sloppy. It was gorgeous sloppy, wonderful sloppy. And it was the only damn way we were going to beat Spinks.”

From The Vault: Every Ali Cover Story

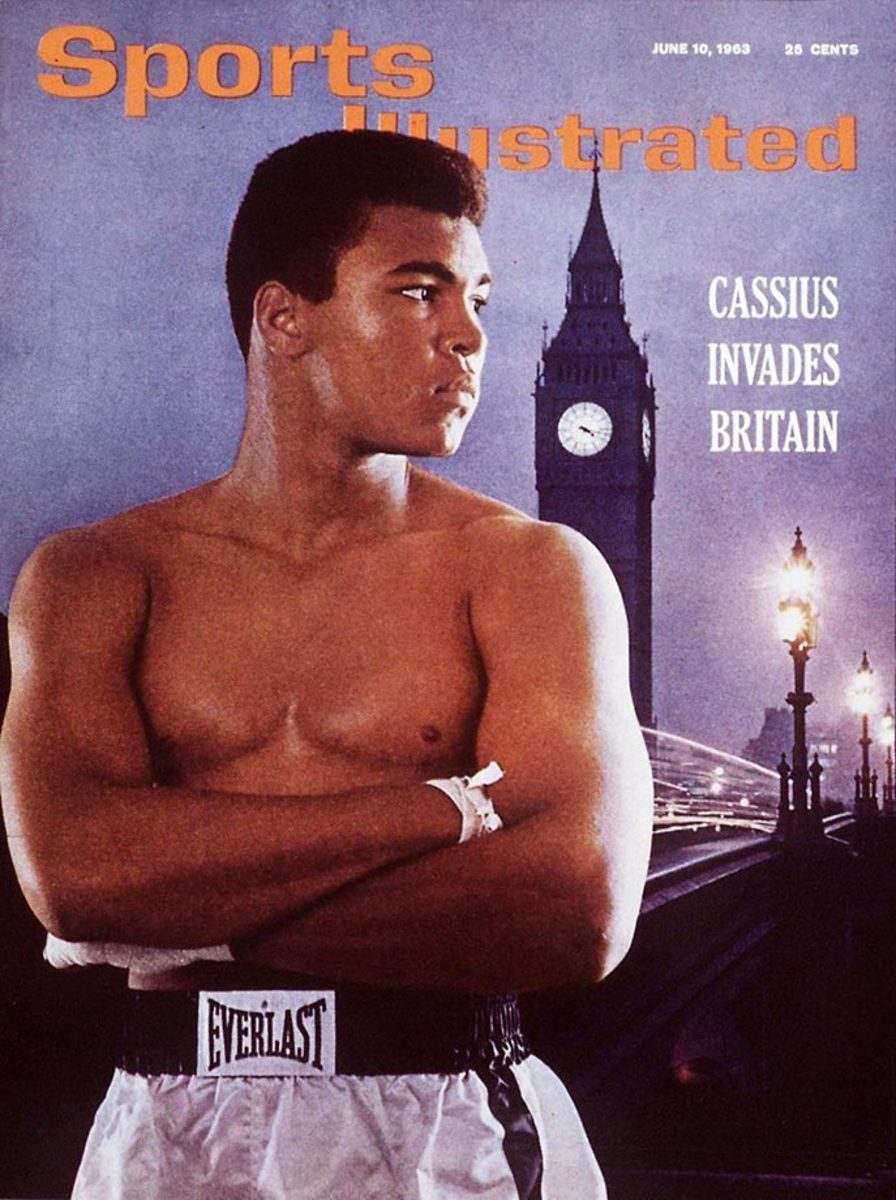

- Cassius invades Britain

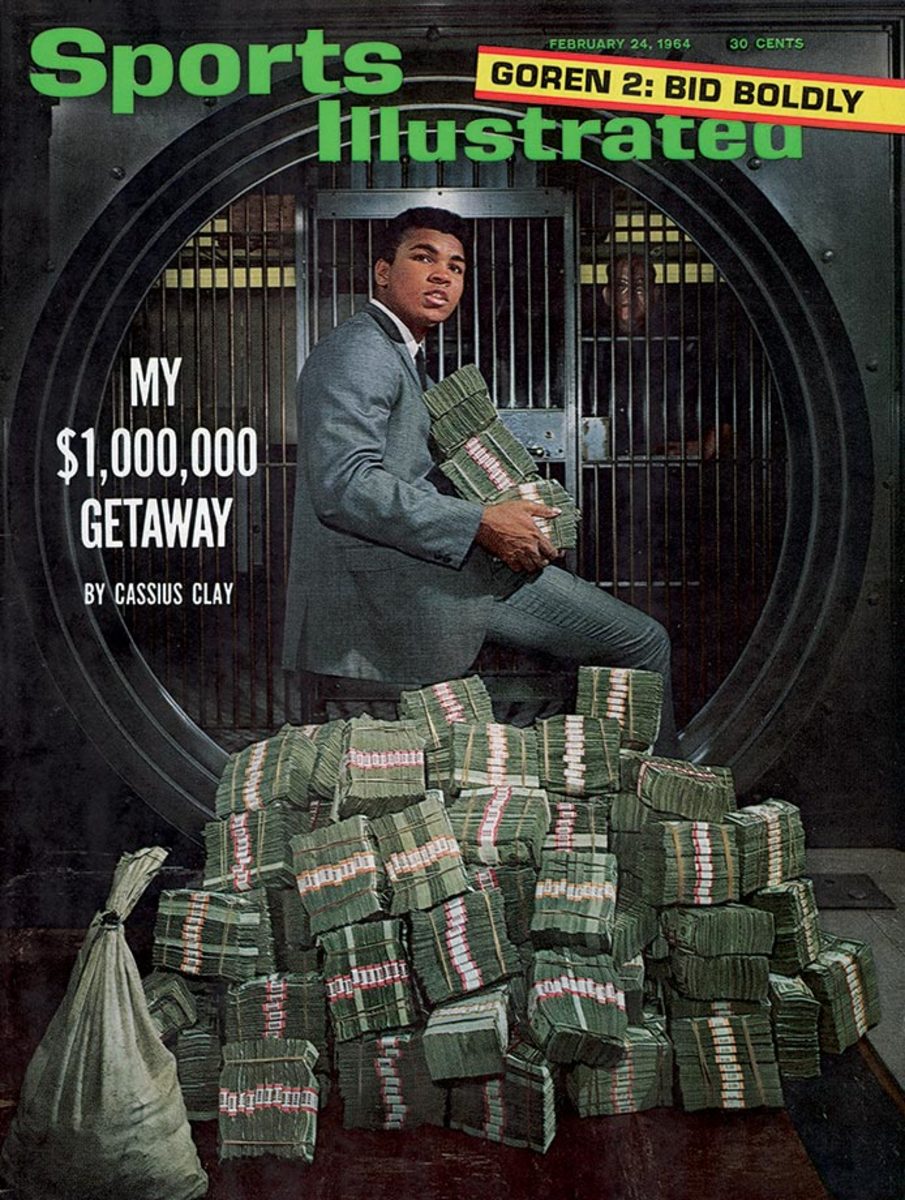

- My $1,000,000 Getaway

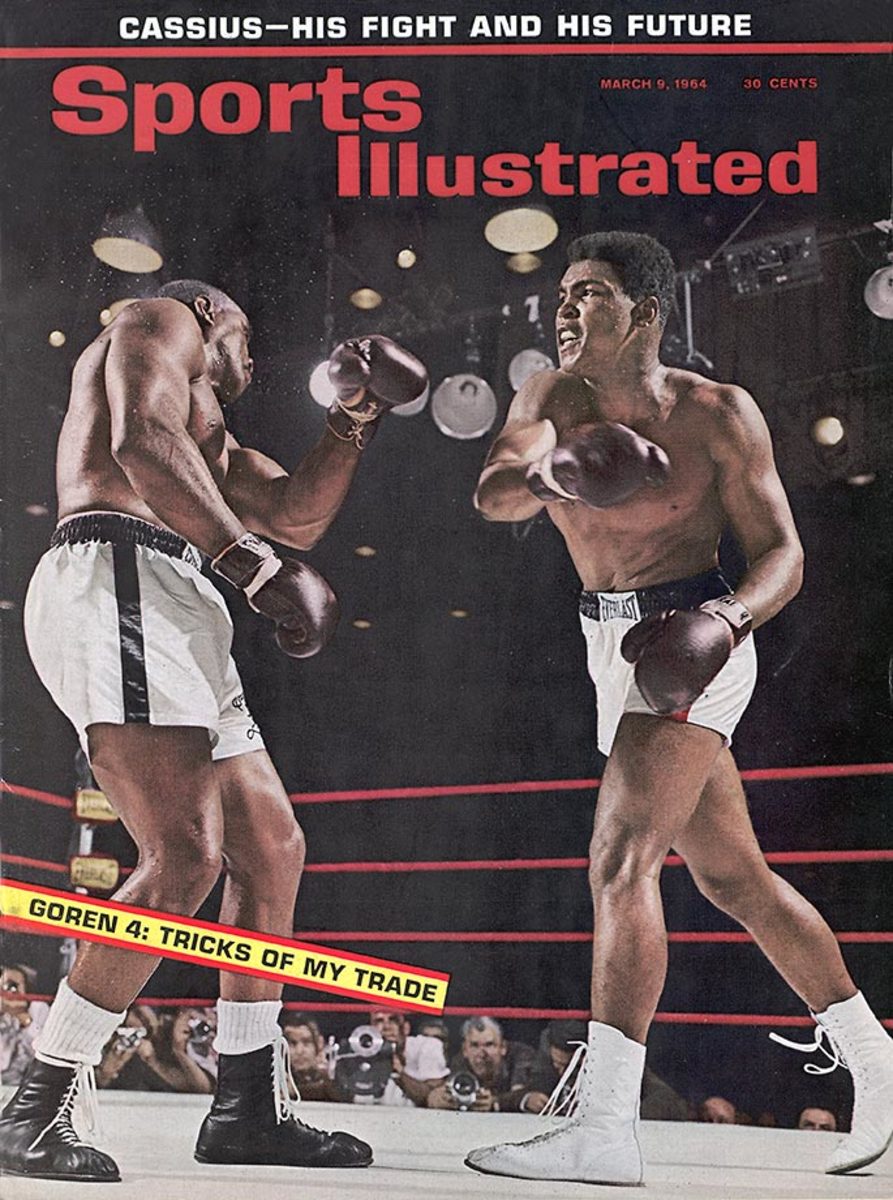

- Cassius—His Fight And His Future

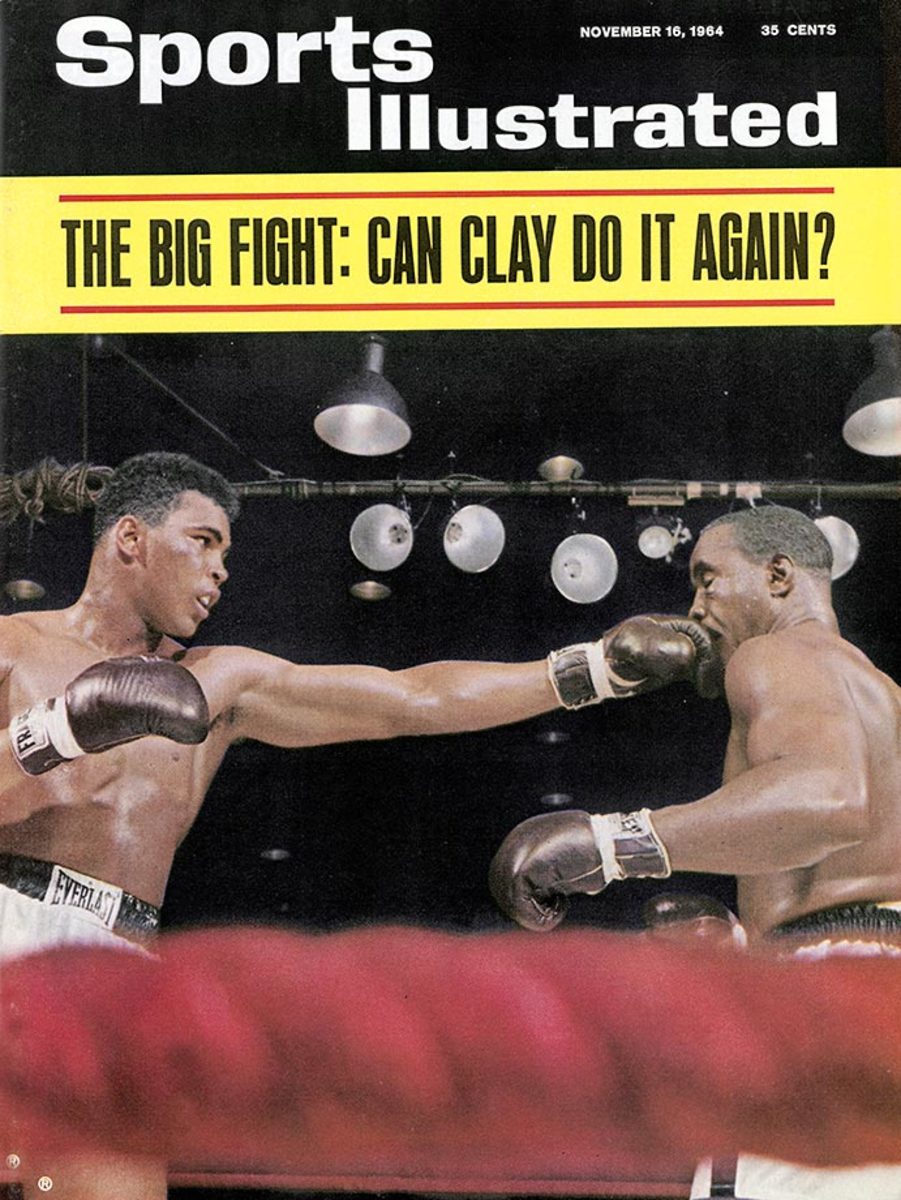

- The Big Fight: Can Clay Do It Again?

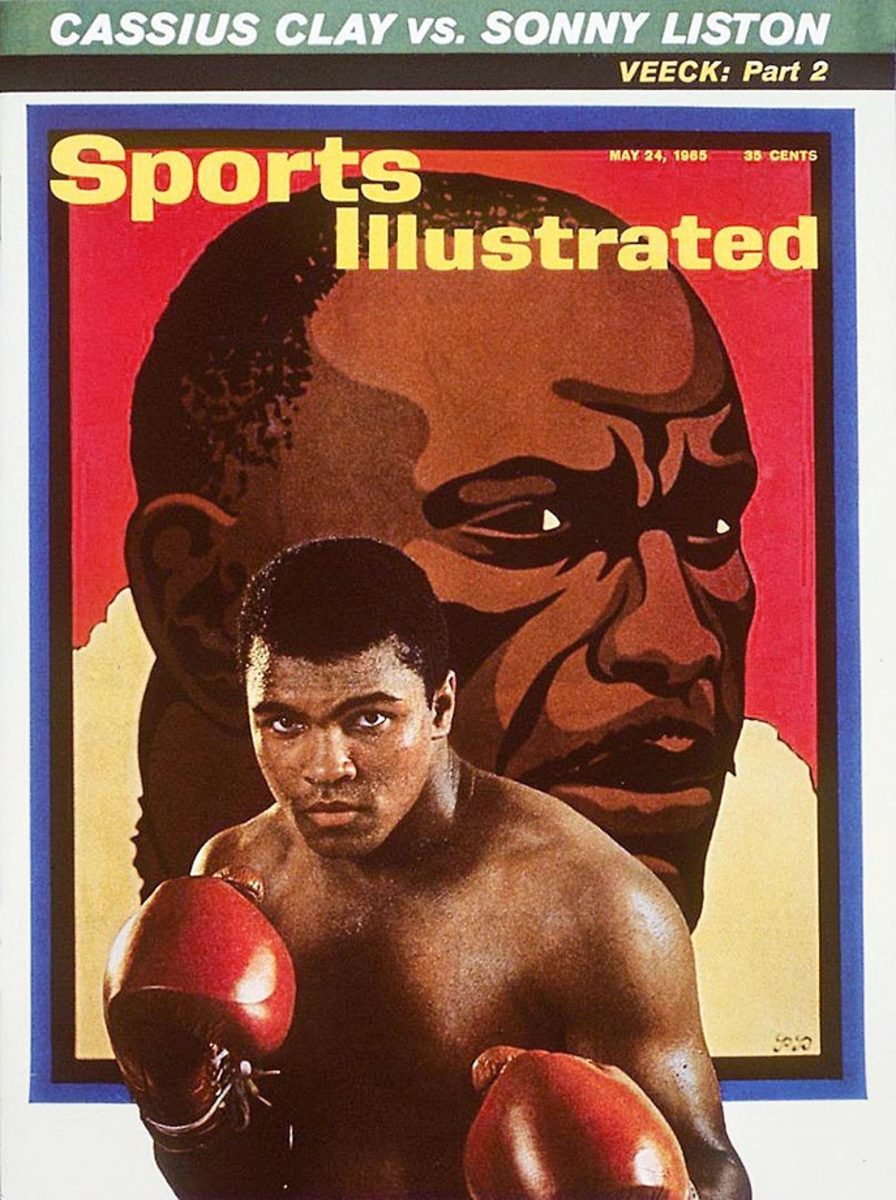

- Cassius Clay vs. Sonny Liston

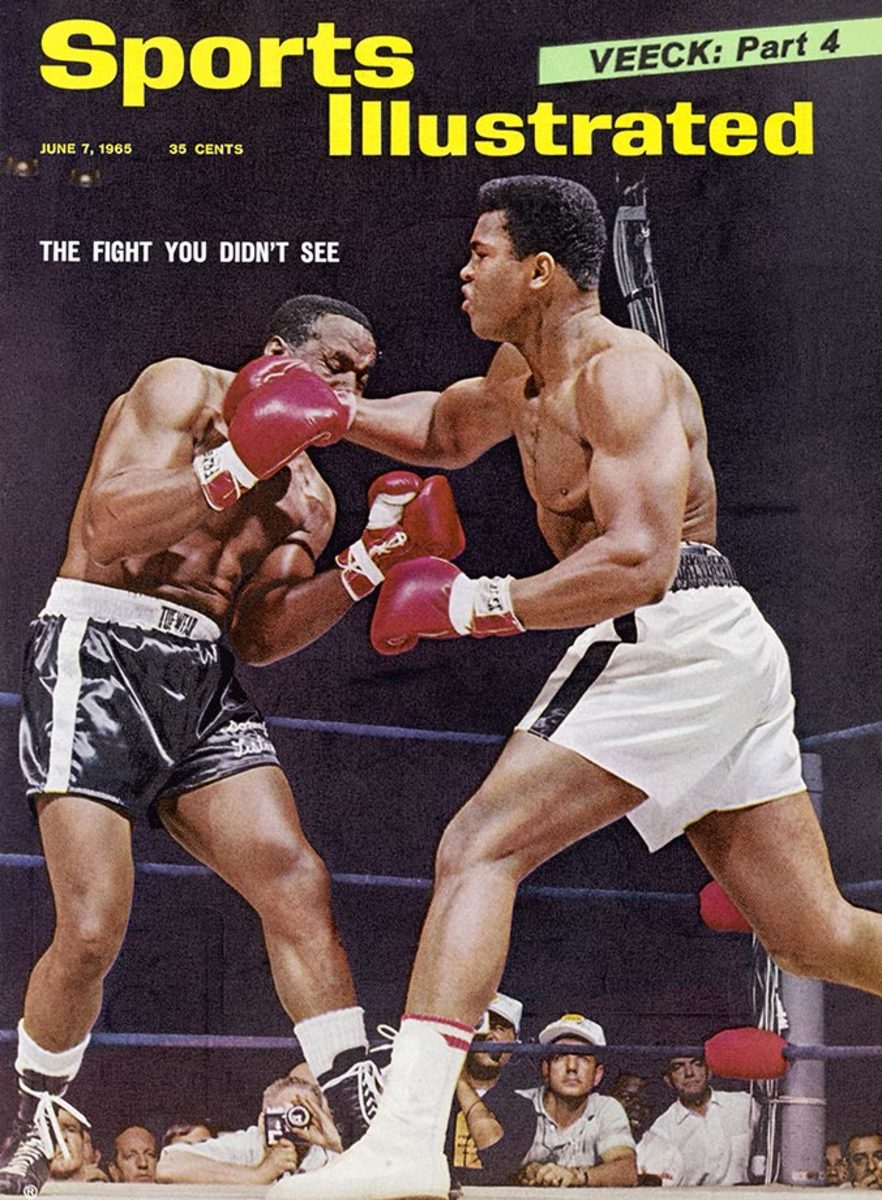

- The Fight You Didn't See

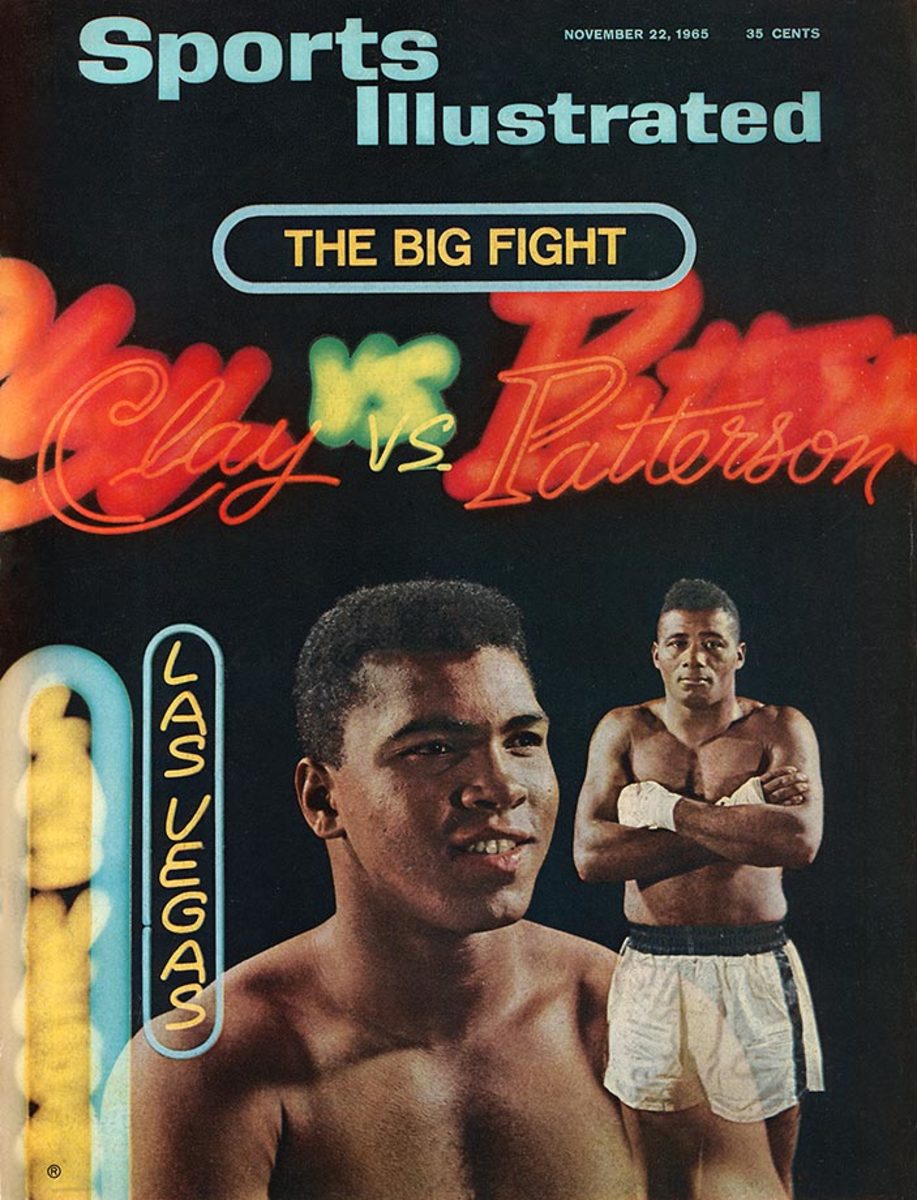

- The Big Fight: Clay vs. Patterson

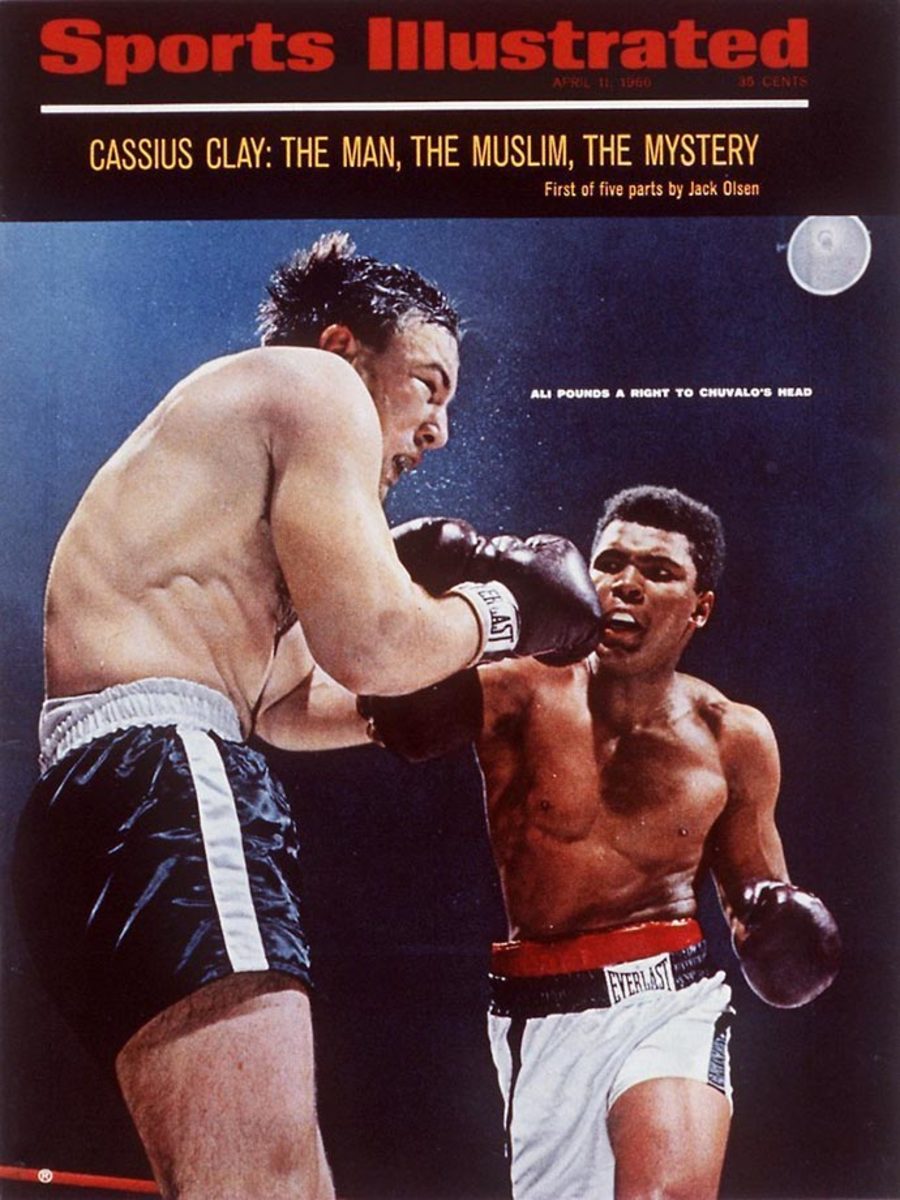

- Cassius Clay: The Man, the Muslim, the Mystery

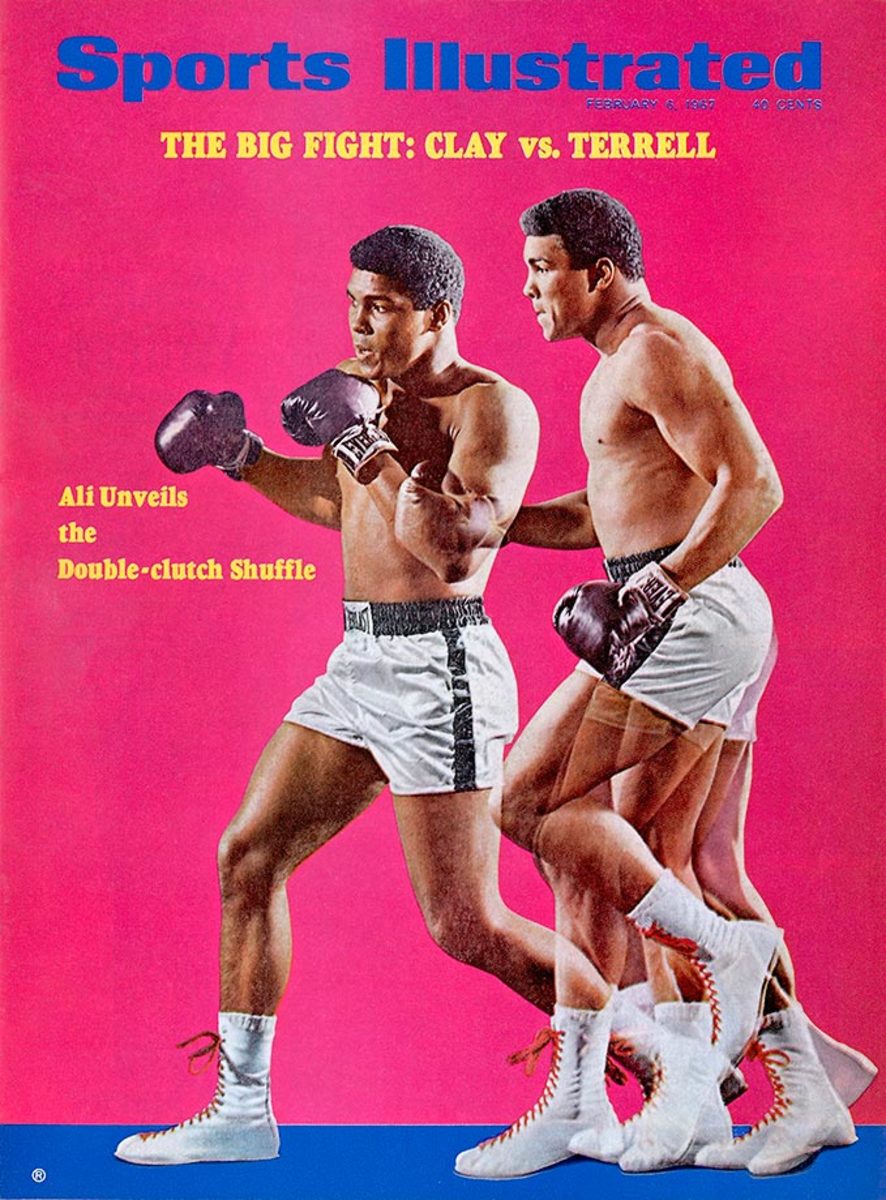

- The Big Fight: Clay vs. Terrell

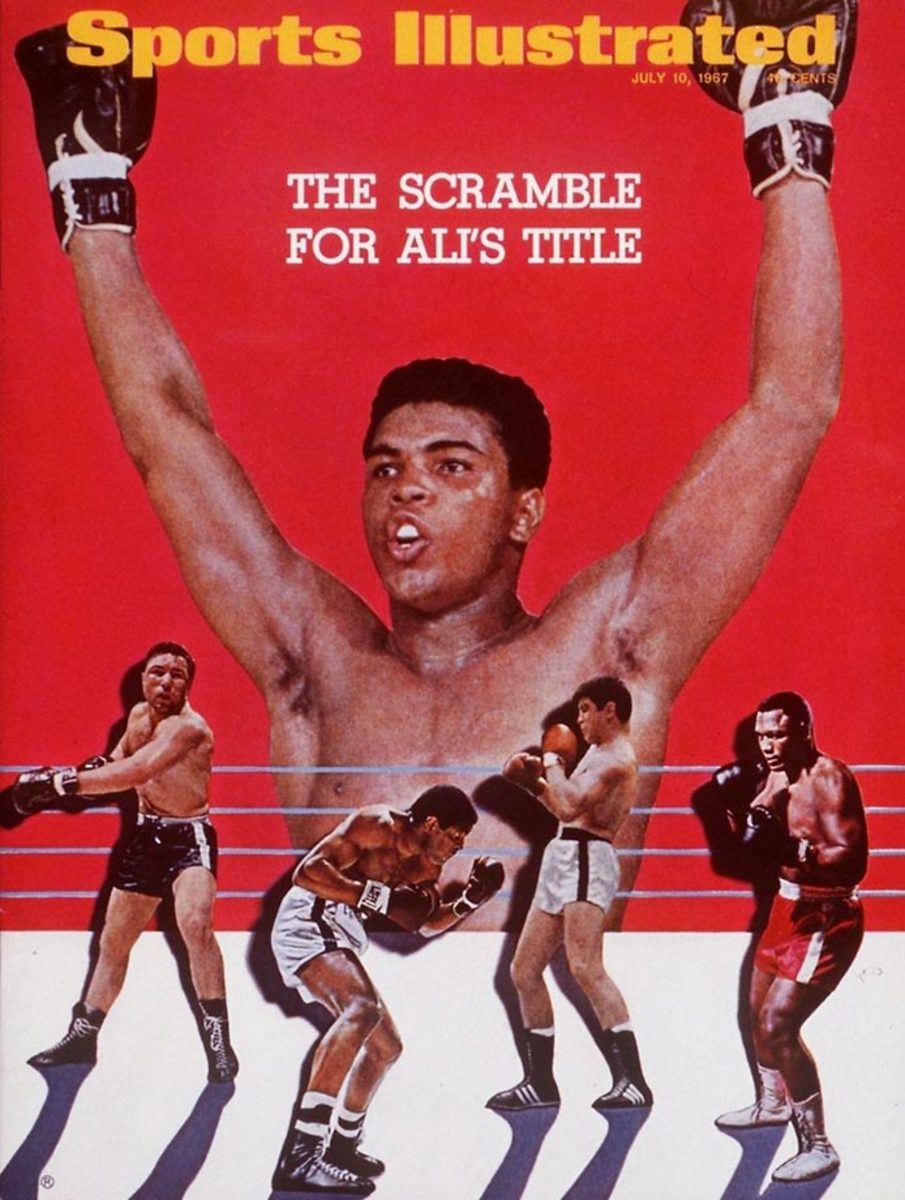

- Scramble for Ali's title

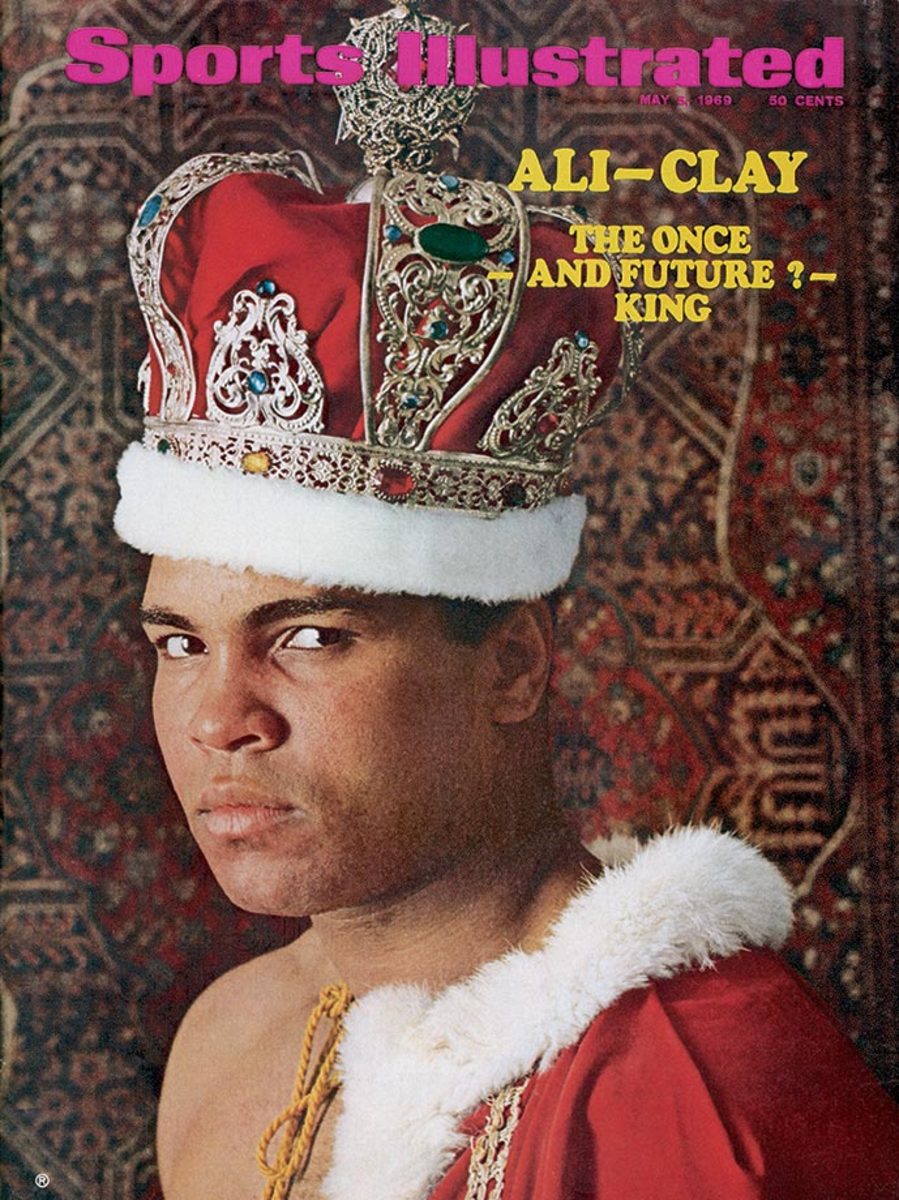

- Ali-Clay; the once and future king?

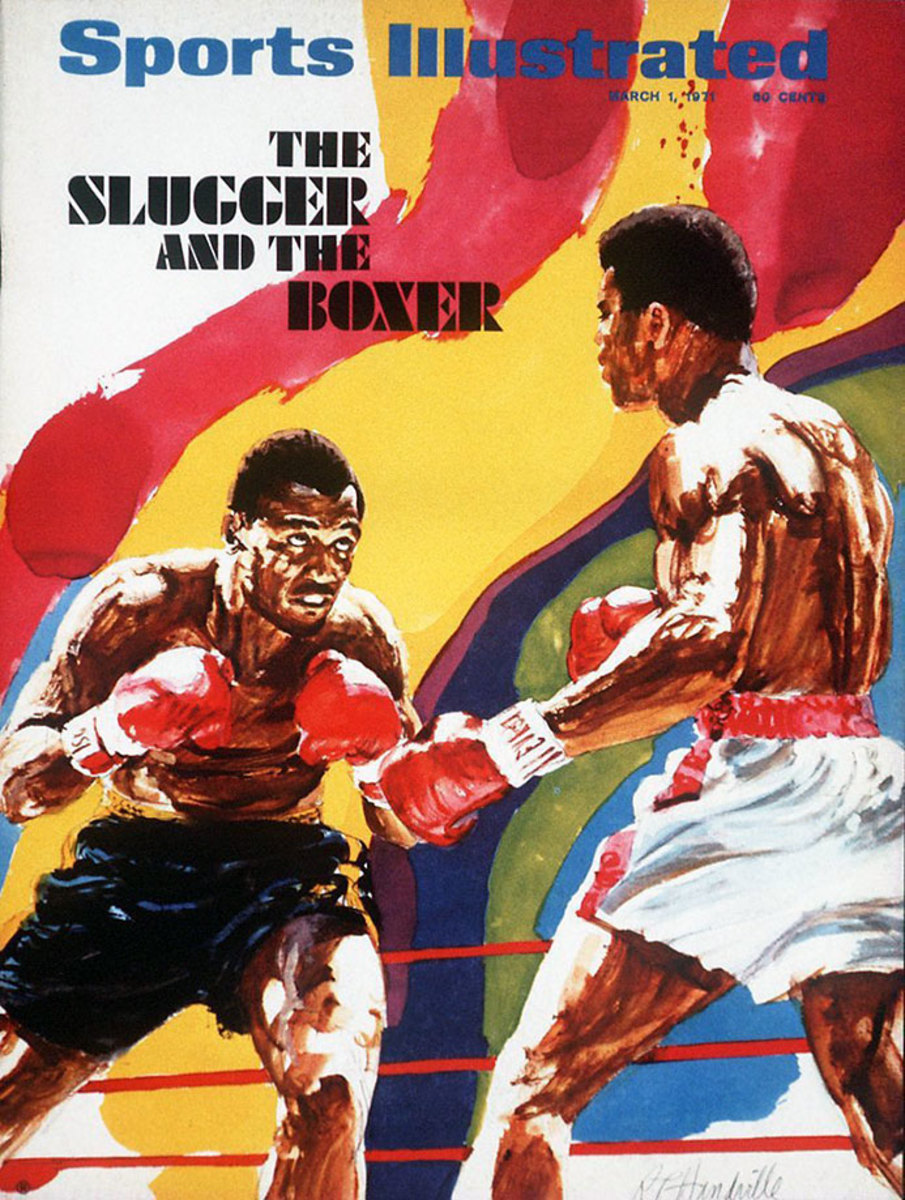

- The Slugger And The Boxer

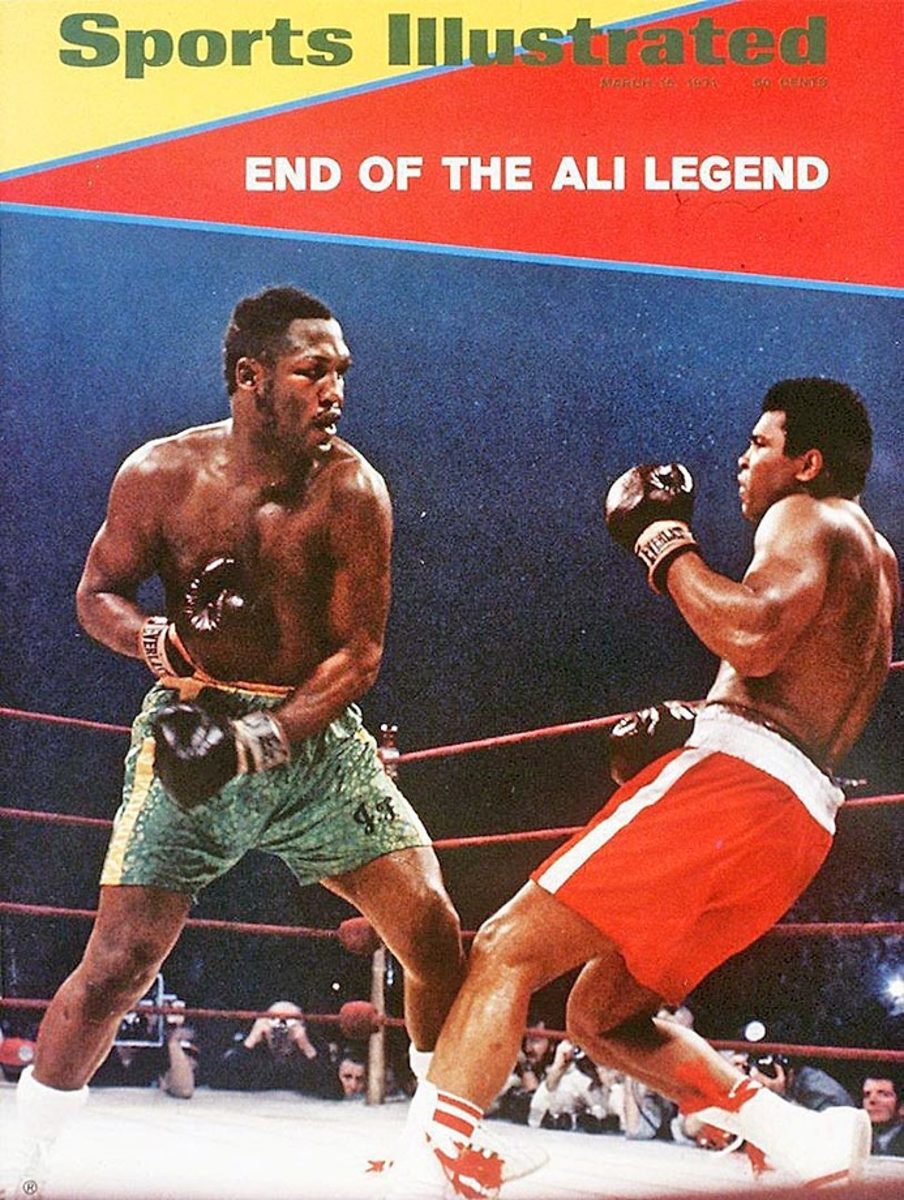

- End of the Ali legend

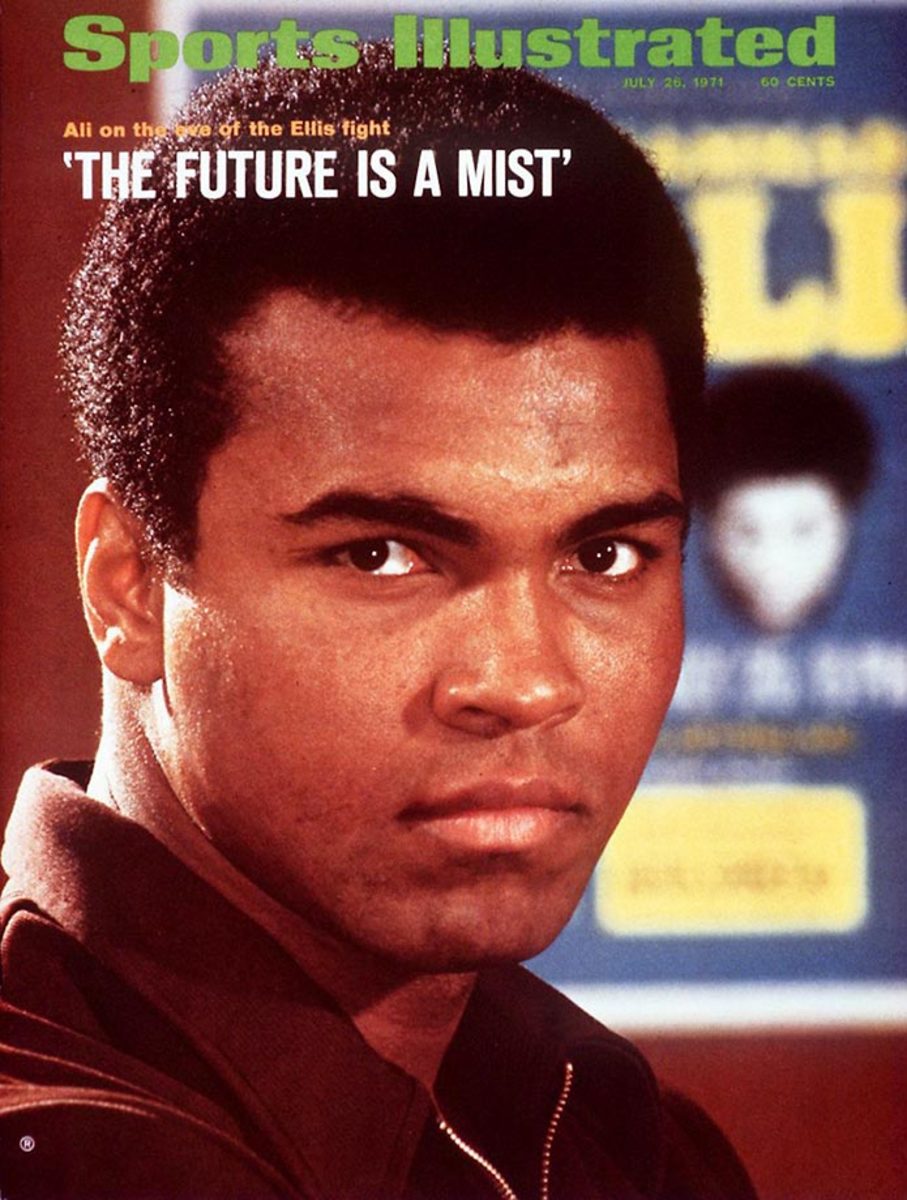

- The future is a mist

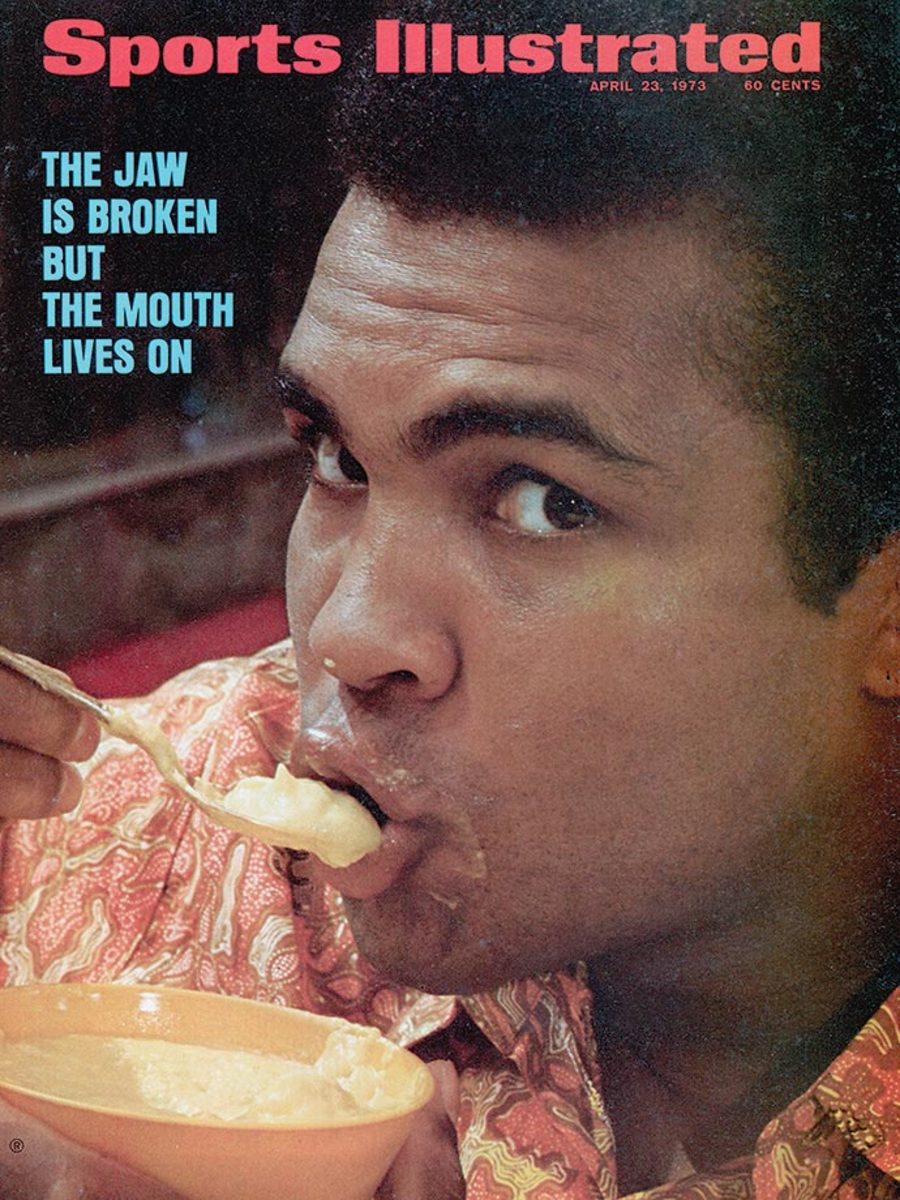

- The Jaw is broken

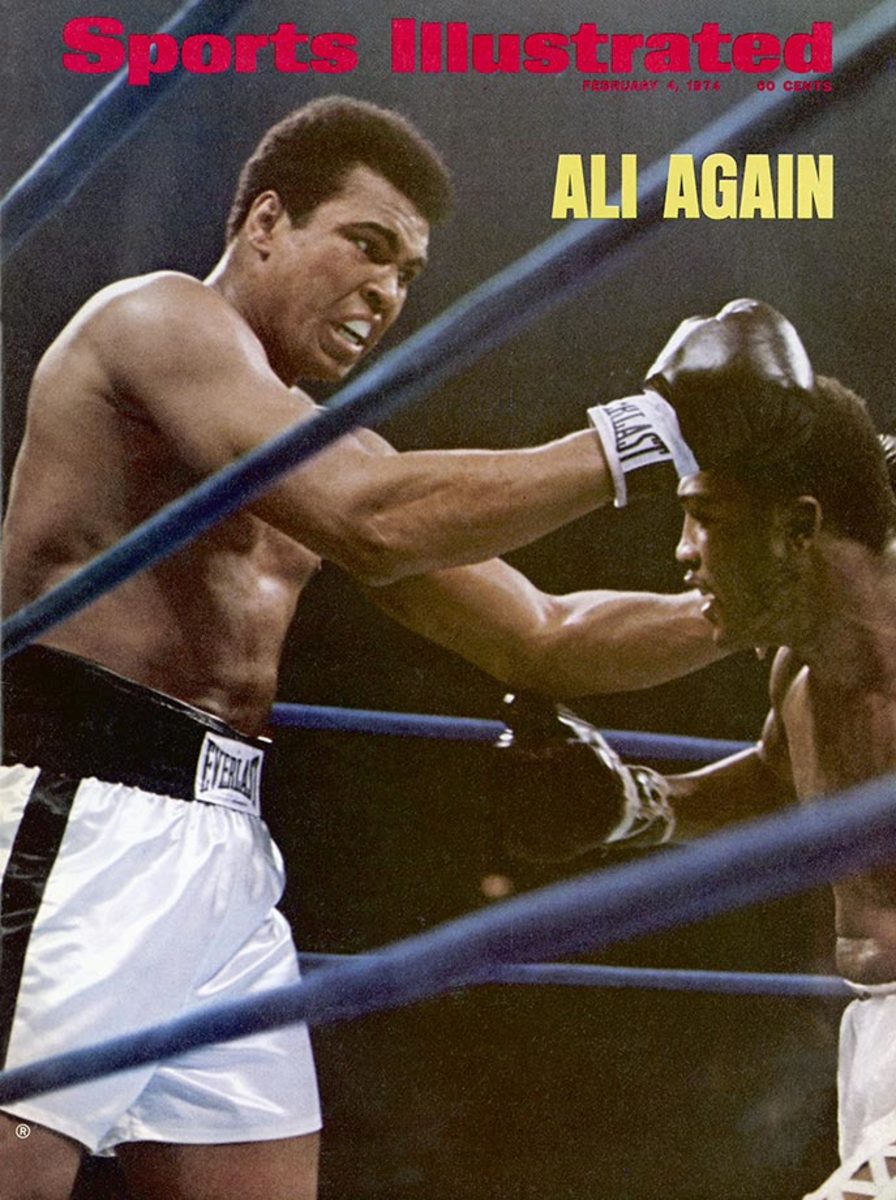

- Ali Again

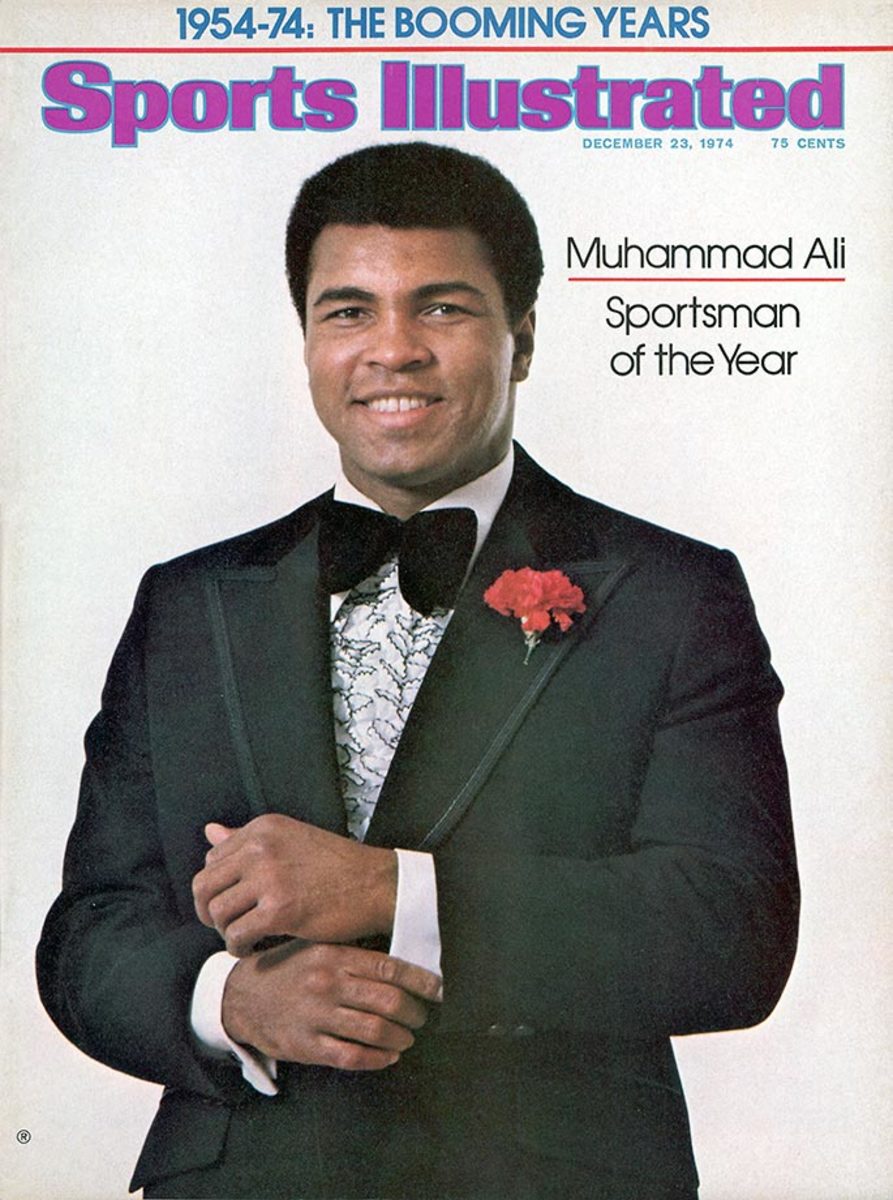

- Muhammad Ali: Sportsman of the Year

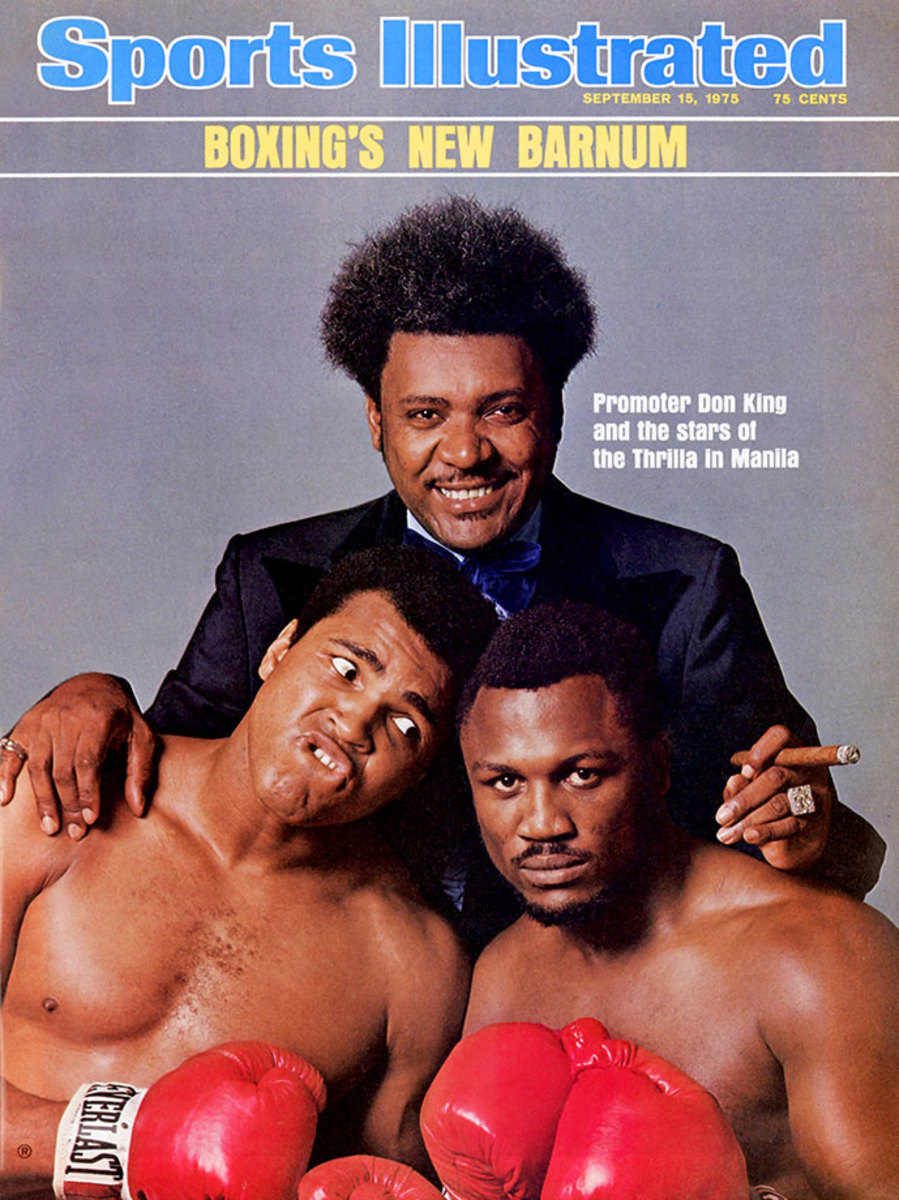

- Boxing's New Barnum

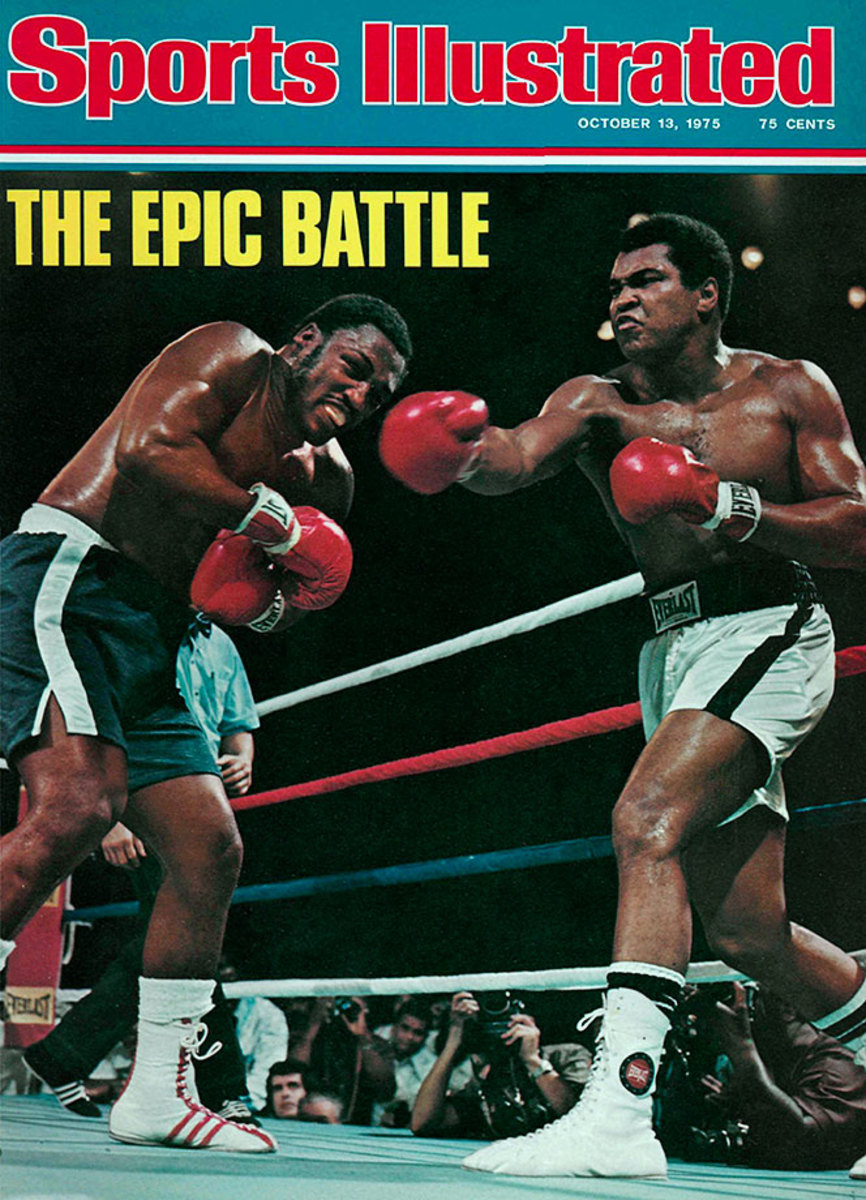

- The Epic Battle

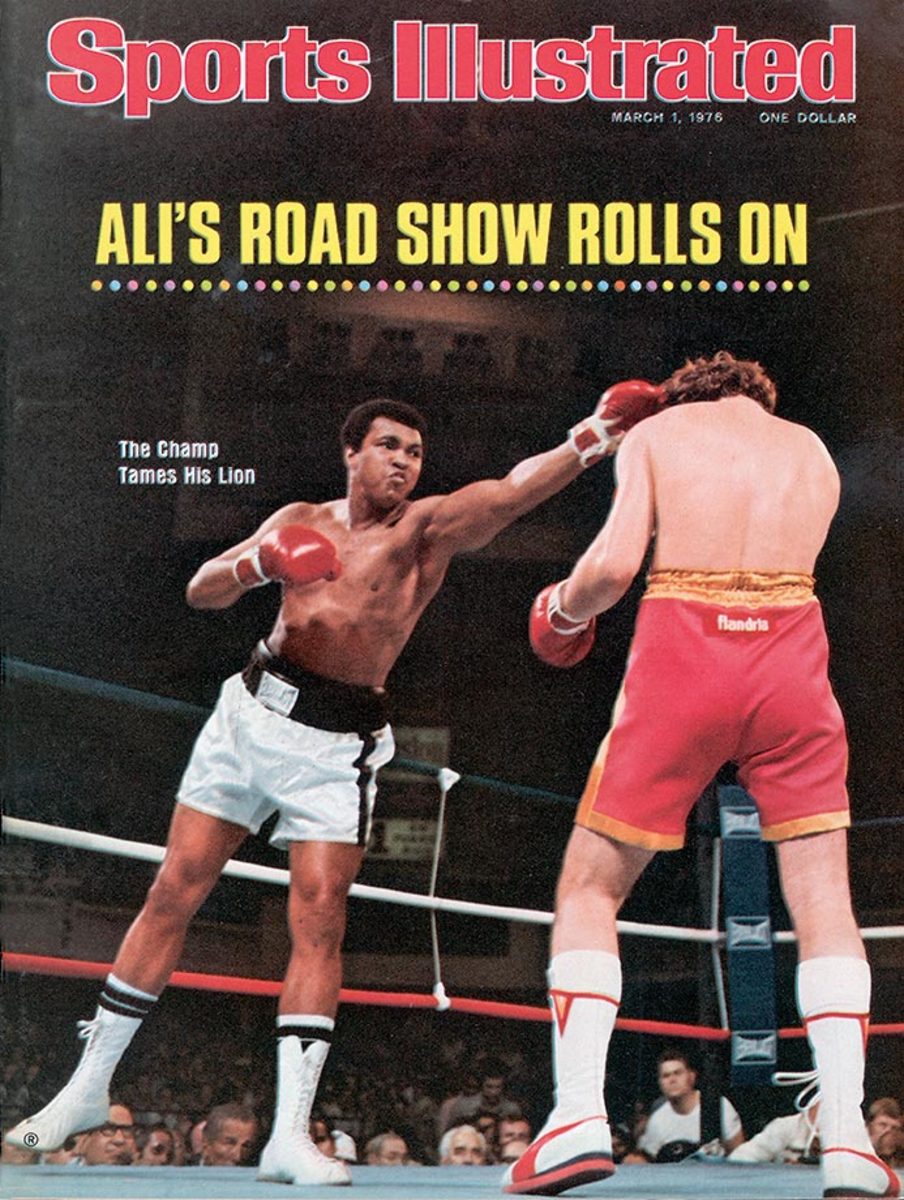

- Ali's Road Show Rolls On

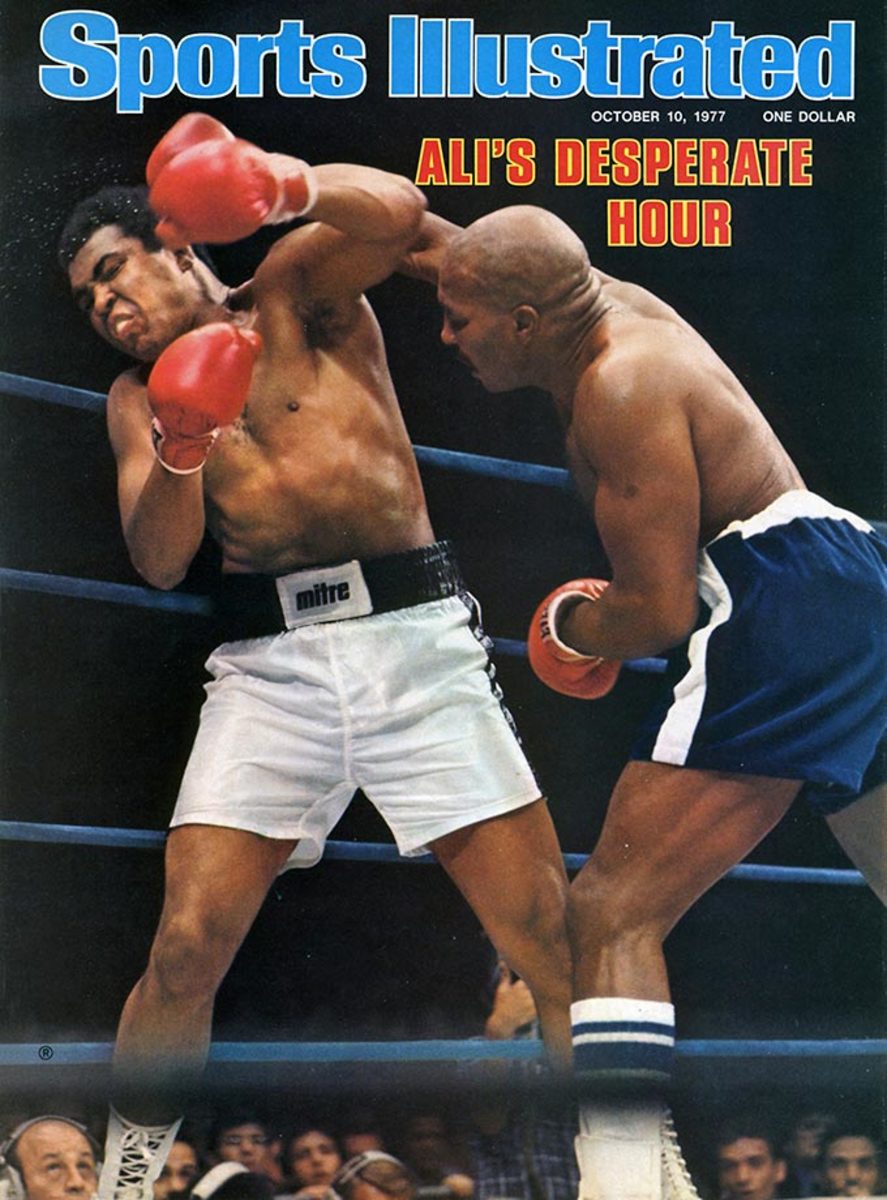

- Ali's Desperate Hour

- The Champ Again

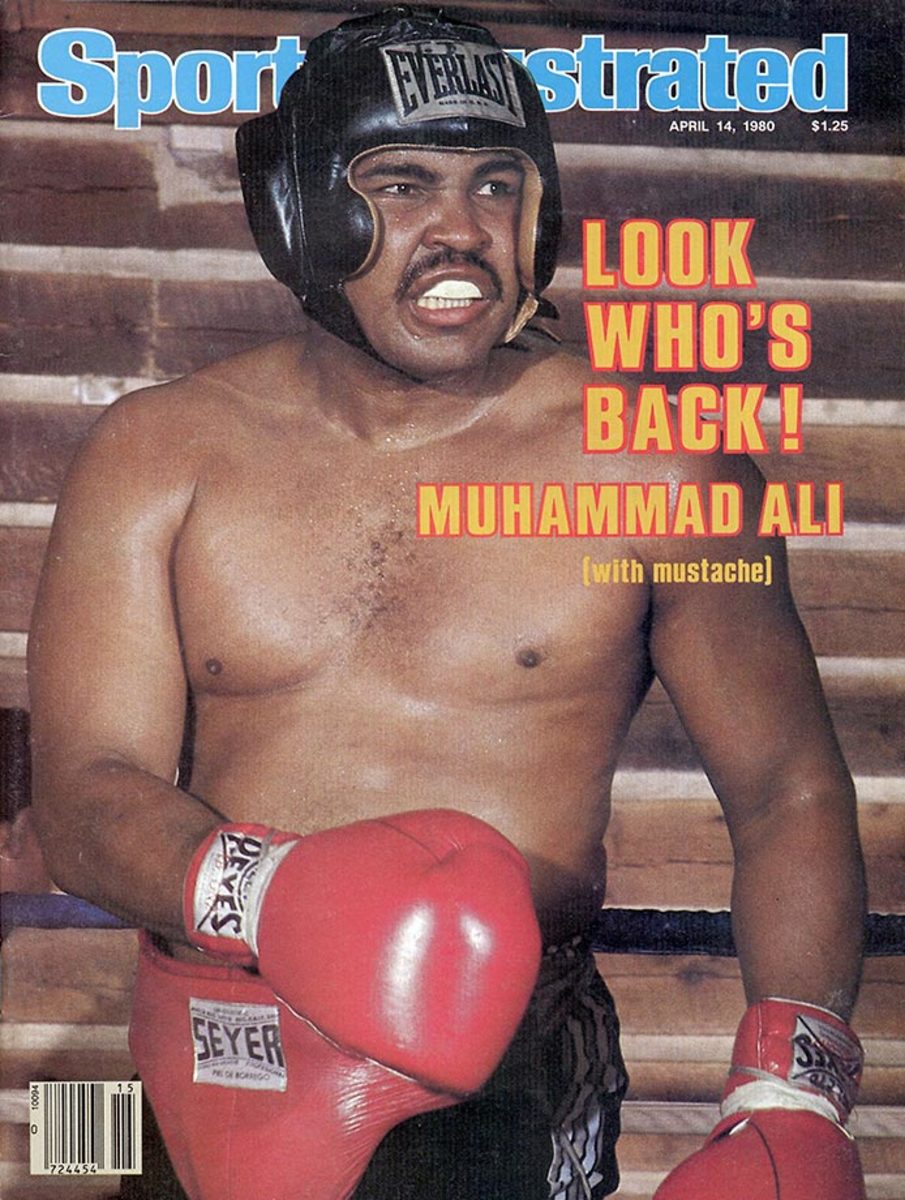

- Look Who's Back!

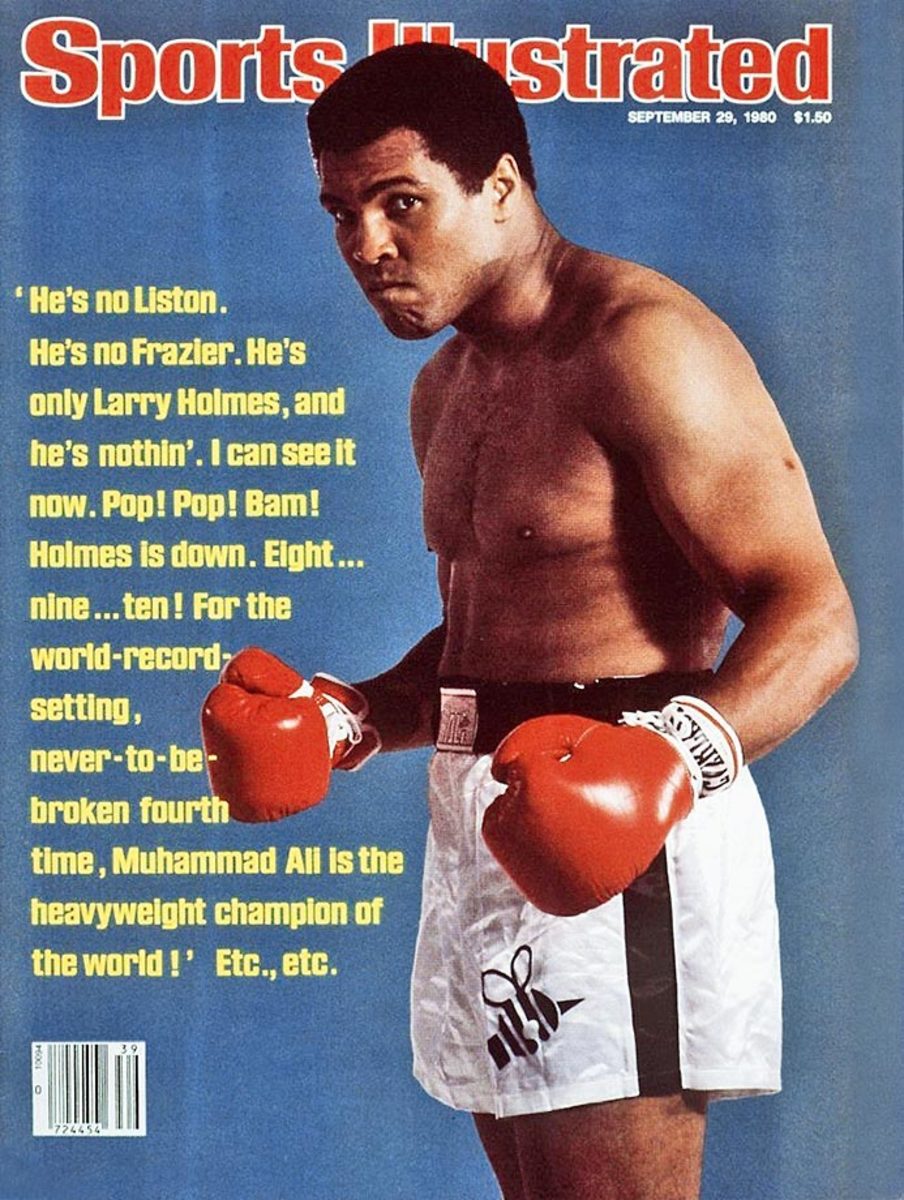

- He's no Liston. He's no Frazier.

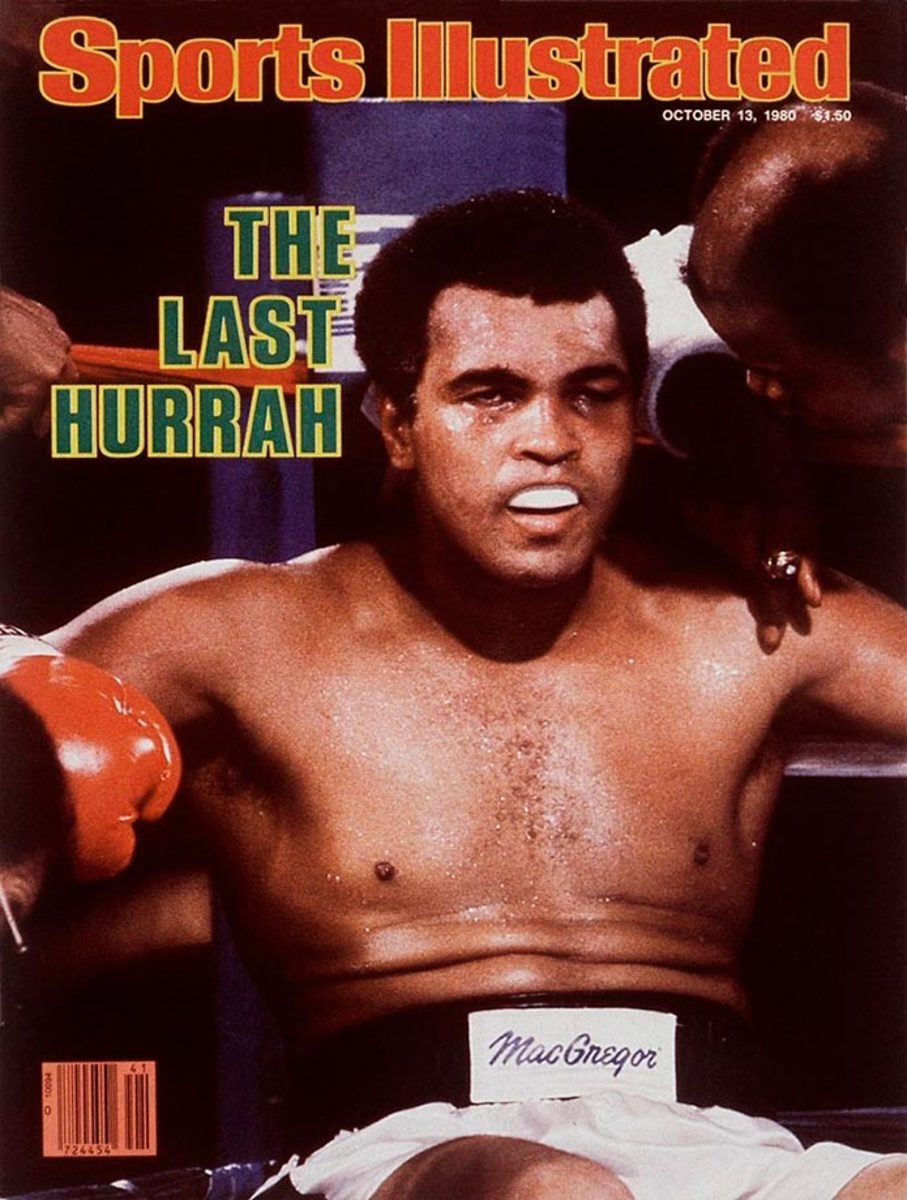

- The Last Hurrah

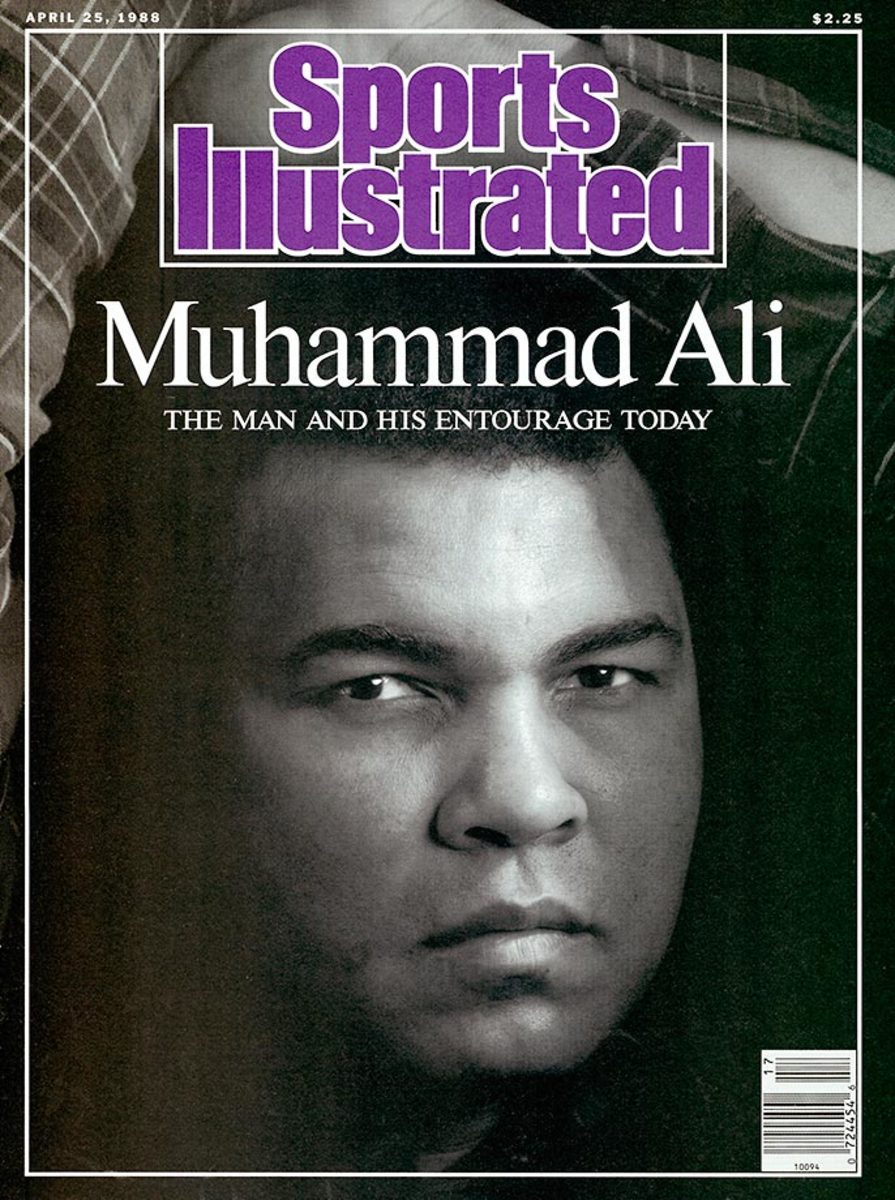

- The man and his entourage today

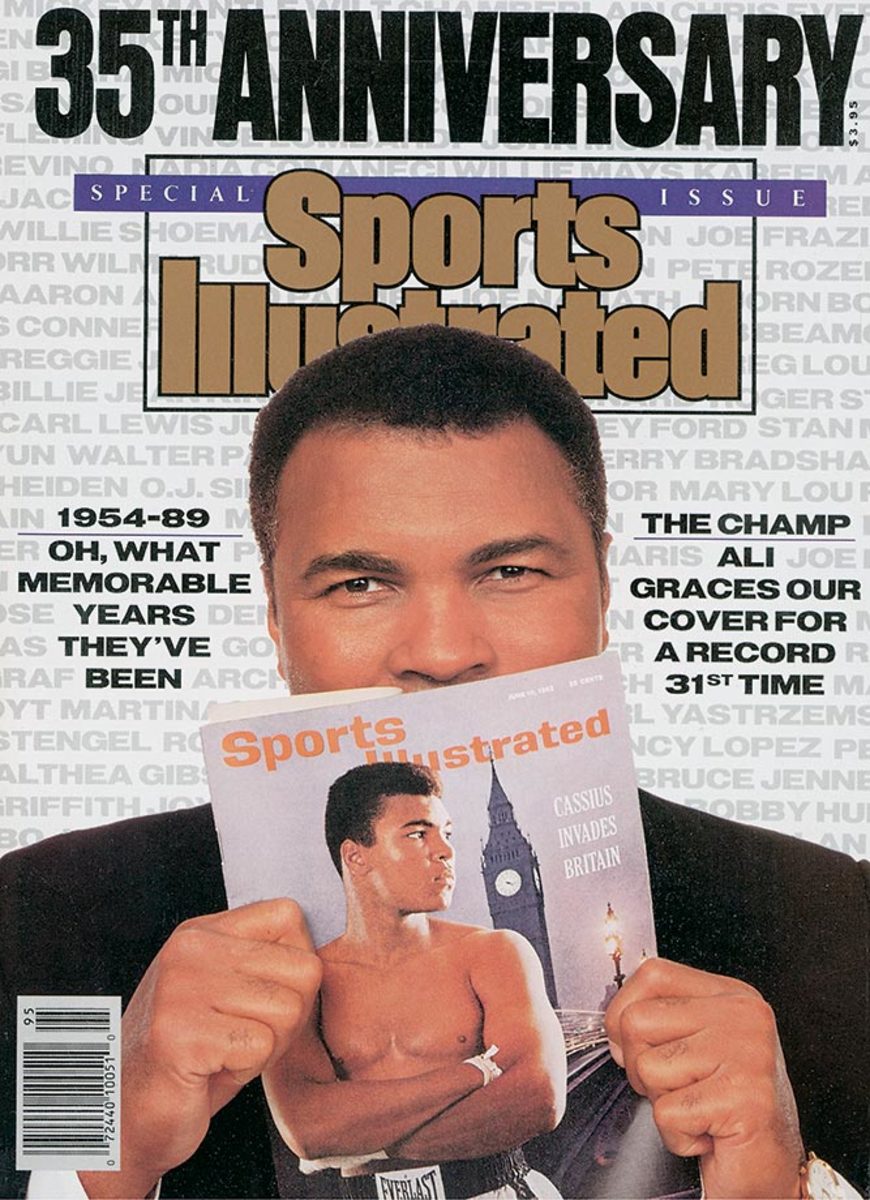

- 35th anniversary

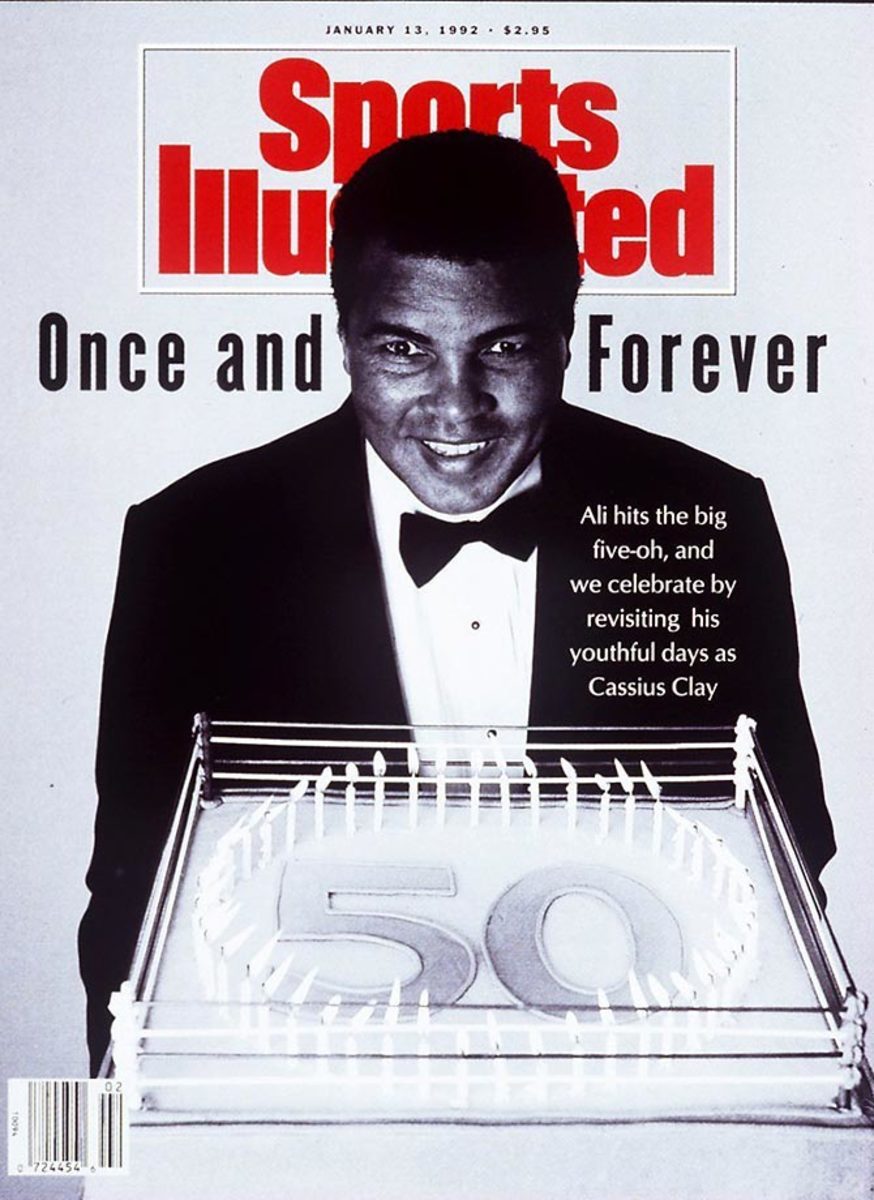

- Once and Forever

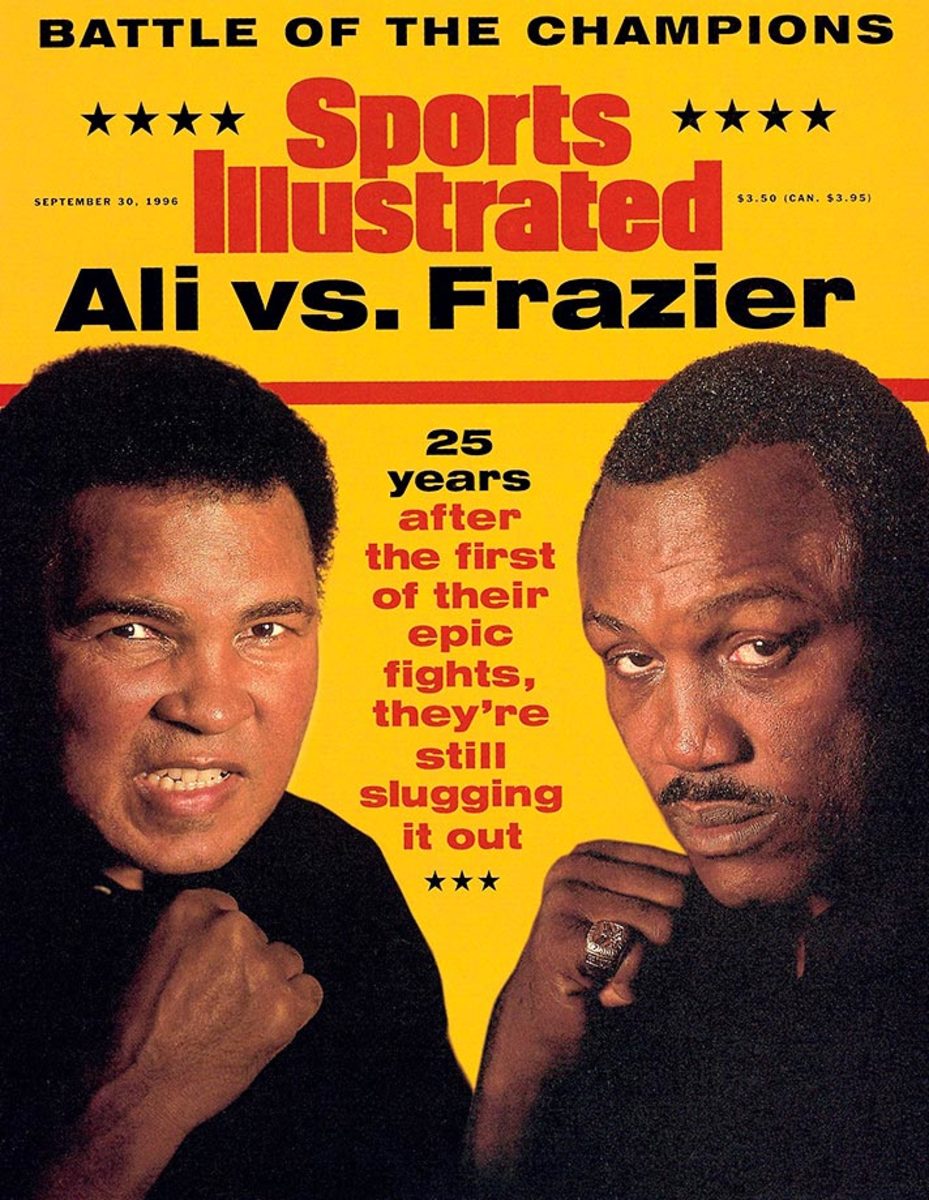

- Battle of Champions: Ali vs. Frazier

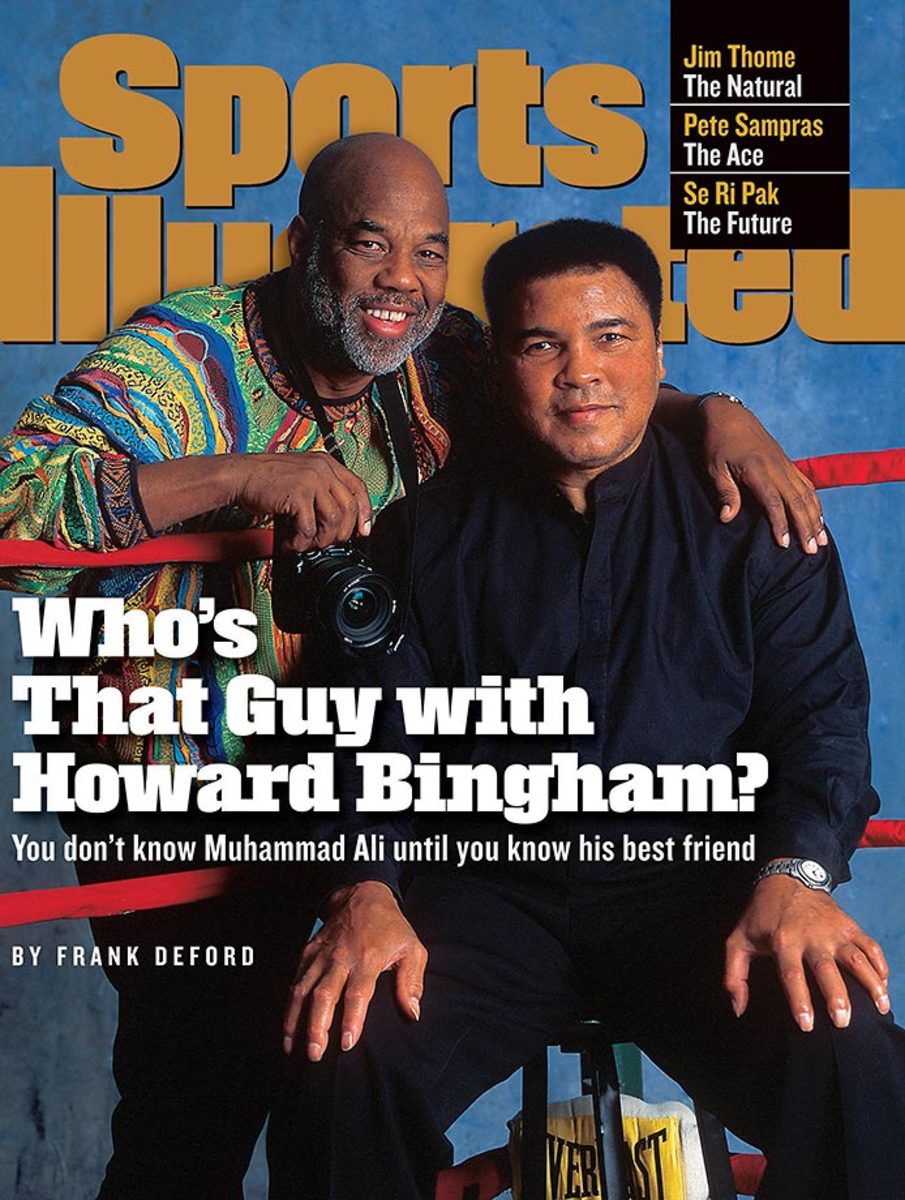

- Who's that guy with Howard Bingham?

The plan was simple. Ali would jab, jab, throw a right and grab. When Spinks came flailing in, Ali would hook his left hand around the back of Spink’s head and pull him into an embrace, effectively limiting Spinks to one or two punches or pulling him off balance. And Ali would dance, baby, dance. He would tie up Spinks and then dance away from him on the break, circling to the right, circling to the left. And the fight went as plotted. From the fifth round on, Dundee was shouting across the ring at Spinks, “Where did he go, Leon? Where did he go?”

Spinks was clearly asking himself the same question. Where Ali assuredly did not go was to the ropes, as he had done while losing his beloved championship to Leon in their fight in Las Vegas in February. Gone was the infamous rope-a-dope, by means of which Ali had coasted for long periods during his last few fights. This was the first time in recent memory that Ali stayed in the center of the ring, circling, jabbing and throwing occasional, if not very accurate, combinations, the first time in years he had not engaged in any extraneous foolishness. And when in doubt, he would seize Spinks in a mighty bear hug. At 221 pounds against 201, it was no contest.

Like many in the mammoth crowd, Referee Lucien Joubert would have preferred something more pure in the way of boxing, and in the early rounds he warned Ali repeatedly as he unclasped Ali’s hand from Spinks’s head. Finally, at the end of the sixth round, he told Dundee that he had taken the fifth round away from Ali.

“For what?” Dundee said.

“For holding. I warned him about it.”

“Now you tell me,” Dundee yelled. “You take a round away from my guy and now you tell me? What the hell were you waiting for?”

But at this stage in the fight it didn’t matter. Now, instead of throwing just one punch after the jab, Ali began unloading combinations, and if they weren’t causing any particular pain, many of them were scoring points.

“Goodbye, Leon!” Dundee shouted.

Spinks looked across the ring at Dundee and smiled. And at the end of the seventh round, when Ali permitted himself the luxury of a little Ali shuffle on the way back to his corner, the outcome seemed clear.

All through the fight Spinks kept looking desperately to his corner for advice, but all was chaos. He had arrived at ringside with an entourage of 11 persons, including a clutch of Marine Corps buddies, and every one of them was shouting instructions. Across the ring, Dundee watched the confusion, then turned and surveyed the usual two dozen or so members of Ali’s team. “Well,” he said, “their crazies can match our crazies, anyway.”

Ali is used to such bedlam. For the 25-year-old Spinks, the situation was serious. It became more so when George Benton, the well-regarded trainer who had masterminded the upset victory over Ali seven months ago, quit in disgust. Overcome with frustration, he walked out on the fight at the end of the fifth round. “My God,” he said, “it’s a zoo.”

Only minutes before the fight, Sam Solomon, Spinks’s principal trainer, had told Benton his plan for instructing Spinks during the fight: Benton would be permitted to give advice only every third or fourth round. They would alternate. One round, Solomon would whisper in Spinks’s ear; the next round, it would be Michael, the champion’s younger brother; then it would be Benton’s turn. Unless, of course, Art Reddon, the gunnery sergeant who had coached Spinks in the Marines, had some counsel he thought might be helpful. And at one point Marshall Warren, Spinks’s accountant, was shouting advice as loudly as any of them.

“Remember,” Solomon told Benton, “if it’s not your turn in the corner and you have something to say to Leon, just tell the guy whose turn it is and he’ll relay the message.”

The situation had been even more chaotic in the dressing room before the fight, when it was discovered that no one among the horde of friends, relatives and functionaries jammed into the room had remembered to bring Spinks’s protective cup, his water bucket and water bottle. “Go get a cup,” Solomon said to Chet Cummings, a public-relations man for Top Rank, the fight co-promoters. “For God’s sake, get Leon a cup.”

“A cup?” said Cummings, a knowledgeable fight man who never dreamed that anyone could be that dumb. Cummings turned to Vickie Blain, another Top Rank employee, and said, “Go get Leon a cup for ice.”

“Not that kind of a cup,” Solomon yelled. “A cup cup, for God’s sake. A cup cup!”

Finally they borrowed a protective cup, two water bottles and a bucket from Mike Rossman, who had won the WBA world light-heavyweight championship earlier in the evening and was sharing the dressing room with Spinks.

“You couldn’t believe the scene in there,” Benton said later. “There’s at least 30 outsiders hanging around getting in everybody’s way. Then Sam tells me how every fourth round I might get to talk to Leon. I mean, I’m no freaking yo-yo. What am I supposed to do? Go in and say, `Remember four rounds ago when I said to. ...’ Then he tells me how we can relay instructions. Now it’s rule by committee. It was amateur hour and amateurs were running the show.”

Benton had not wanted to be there at all. The first fight had been quite enough. But in July he had received a letter inviting him to New Orleans as a special guest. The letter was from Mitt Barnes, Spinks’s manager in absentia. Benton had not replied and had decided not to go. He knew Solomon didn’t want him there.

But then, two weeks before the fight, as Spinks’s training sessions grew less and less productive, Michael Spinks and Butch Lewis, a Top Rank vice-president who at one time was in charge of Spinks’s career, had convinced Leon that he needed former middleweight contender Benton in his corner. After four phone calls Lewis finally persuaded Benton to come. He arrived nine days before the fight.

“When I got there I saw Leon was doing all the wrong things,” Benton said. “He’d forgotten all the things I had him doing for the last fight. The boy could be a hell of a fighter but he needs a teacher, and I can only do so much for him in a week or two. He’d lost his jab. He wasn’t bobbing and weaving. I told him, `Leon, it’s about time you got to work.’”

Benton went to work, but there was little he could do about what was going on inside Spinks’s head. The young man has a deep love for his family and a great loyalty to old friends. He tries desperately to make them all happy, and when squabbles began during the weeks before the fight Spinks was deeply disturbed.

Seven days before the fight, there was a shouting match with Michael. Later Michael said, “I laid something on him I couldn’t get off my mind. I told him that I had to chase him to New Orleans, that he was trying to run away from the family and that he owed them more than that.” After the argument Leon went out to train. As he began jumping rope, tears began to stream down his cheeks.

That night, as he had for many of the previous nights, and as he did for the rest of the nights leading up to the fight, Spinks fled alone to the many small and dangerous bars deep inside the New Orleans ghetto. There he tried to drink away the pain.

“He was drunk every night he was here,” said Bob Arum, the Top Rank president. “Leon went to places our people didn’t dare go. I’m surprised he didn’t wind up with a knife in him.”

At one point Spinks moved out of the fight headquarters at the Hilton Hotel and disappeared. No one, not even Solomon, knew where he had gone. “He had left the hotel and moved into a house and didn’t tell anybody where it was,” Butch Lewis said. “Nobody knew how to reach him. We almost went crazy. Finally we had to get a policeman to beat on a policeman who was part of Leon’s security guard to find out where he was.”

While Spinks trained and drank his way through the disharmony, Ali was maintaining his strenuous training pace. He rented a yellow brick home near Lake Pontchartrain, north of town, and there he ran each morning and there he suffered on the green rubbing table set up in the living room.

Every morning at seven, after running between three and five miles, Ali stretched out on the table while trainer Luis Sarria held his ankles with powerful hands, and he went through 12 groups of varying sit-ups, doing 30 or so in each group. The last 40 days before the fight he did 8,014 sit-ups, a number logged by one of his many aides.

On the fourth day before the fight, after Ali had complained of unnatural weariness after a workout, a local doctor discovered that his blood was low in salt, iron and potassium. After that, each morning with his breakfast of two trout, scrambled eggs and two slices of unbuttered whole-wheat toast, Ali swallowed 11 pills to make up the deficiencies.

“God, I have suffered and suffered and suffered. It really hurts,” Ali said one morning from the table. He lay face down staring at a green flowered rug, his arms dangling almost to the floor as Sarria’s fingers worked on his body. “The last fight. It’s time for a new life. I’m going to put on a three-piece suit, carry a briefcase and fly around the world working for human rights and dignity. I’m going to form my own United Nations with a headquarters in Washington and the flags of the world flying from the top. I’m going to have a big warehouse in Cleveland filled with food and clothes, and when there is a disaster anywhere in the world I’m going to fly there in my Learjet and help the people. I don’t want to fight no more. I’ve been doing it for 25 years and you can only do so much wear to the body. It changes a man. It has changed me. I can see it. I can feel it.”

“I think this time he is ready,” said Dundee, who had been watching Ali get messaged. “He has been cruel to himself. The bricks are all there, but he is 36 and they can tilt and fall. Nobody knows what’s inside. What I’m counting on is how badly he wants to win it for the third time, to be the only man ever to do it. He has a sense of history. And, let’s face it, Ali is not like other men.”

A day later Benton was saying pretty much the same thing. Despite his nocturnal adventures, Spinks had trained hard. He was in excellent shape. Benton could see no way he could lose. Yet... ?

“Forget all the nonsense that has been going on around him,” Benton said. “This kid has no business losing this fight. No business at all. I can’t see anything the other guy can do to beat him. Ali can’t win this fight. The only way he can win is if Leon falls on his face. Or if he lets what is inside his head beat him. But I’ve said that so many times about Ali before. Liston. Foreman. Frazier. The draft thing. Ali always comes up on his feet. It’s like there is a mystical force guiding his life, making him not like other men. When I think of that--and when I think of the fight--it’s scary.”

Then came the fight, and Benton’s scary feeling turned to outrage. After leaving the corner he watched a few more rounds on a TV monitor in the dressing room. After the 12th round he picked up his equipment bag and left.

Back in the ring, Spinks was looking to his corner again.

“Wiggle,” Michael shouted at him.

“Wiggle.”

“Give him the old gusto,” Solomon yelled.

Equally cogent advice was shouted by the others. In the 13th, so far behind that he could win only by a knockout, Spinks was advised by one of his cornermen to start jabbing to the body. Why not? It was as good as telling him to wiggle or to give him the old gusto.

And then it was all over, with Ali still dancing, and Spinks doggedly chasing him, still trying to find him, still trying to hit him.

The decision was announced: 10-4-1, 10-4-1, 11-4. And Spinks was there in the middle of the ring, one of the first to raise his idol’s right arm in victory. Score one more for the venerable master. And shed a tear for the kid from the ghetto who really never had a chance.

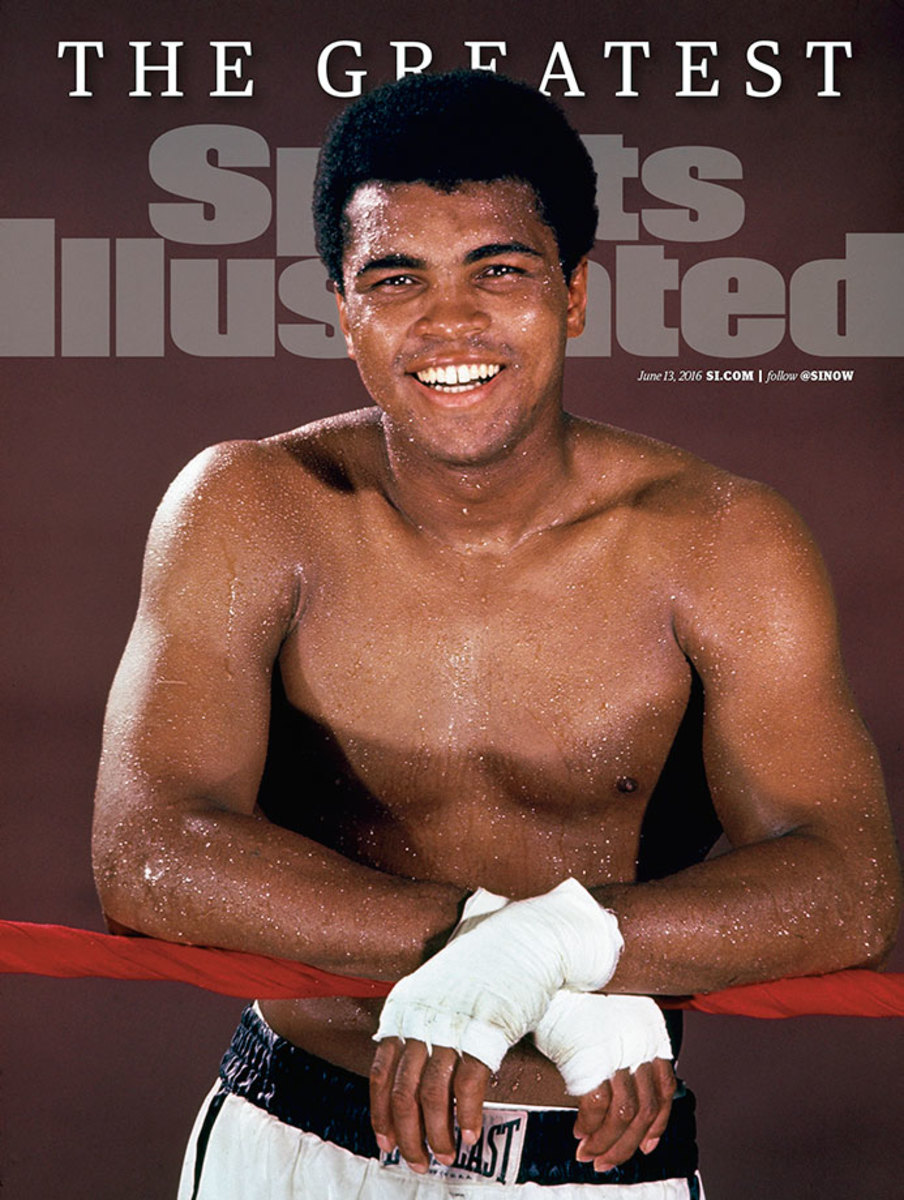

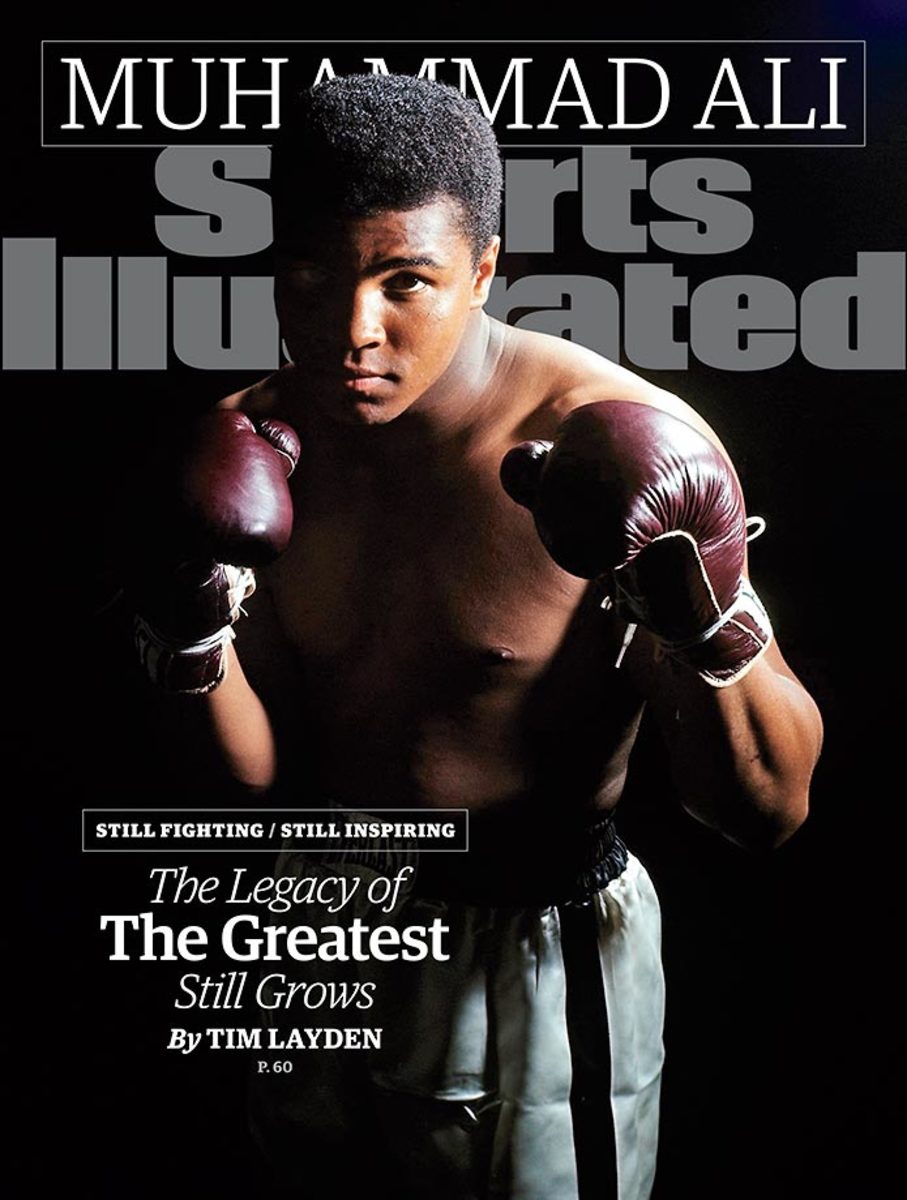

Muhammad Ali's SI Covers

June 10, 1963

February 24, 1964

March 9, 1964

November 16, 1964

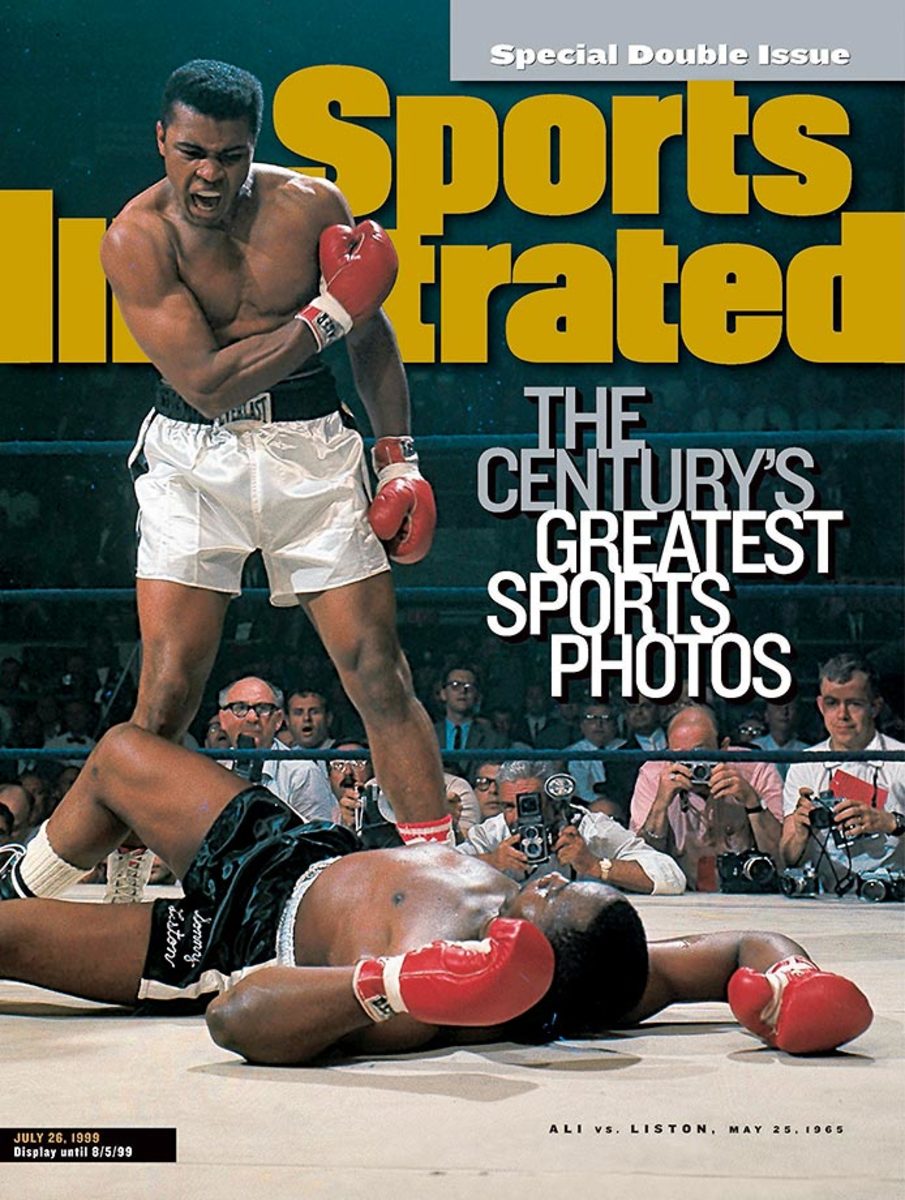

May 24, 1965

June 7, 1965

November 22, 1965

April 11, 1966

February 6, 1967

July 10, 1967

May 5, 1969

March 1, 1971

March 15, 1971

July 26, 1971

April 23, 1973

February 4, 1974

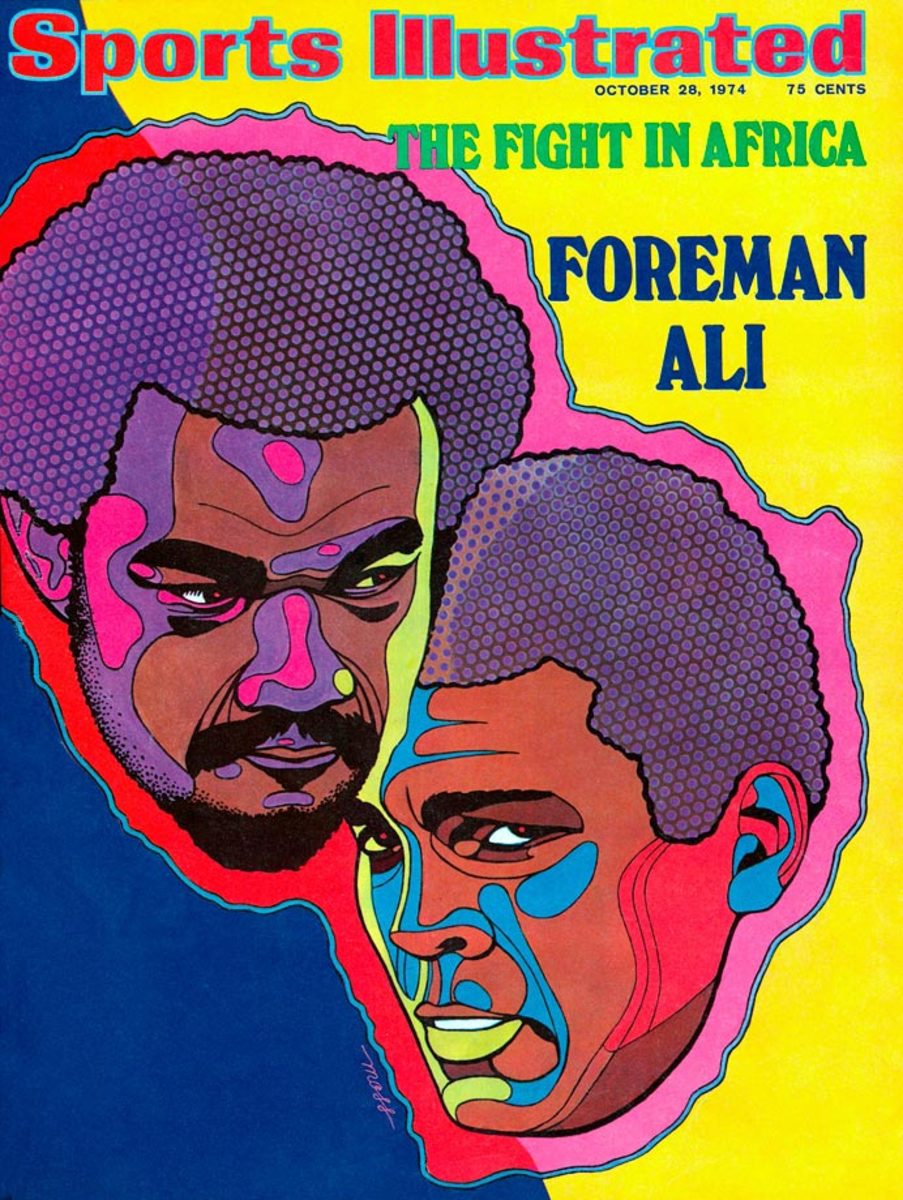

October 28, 1974

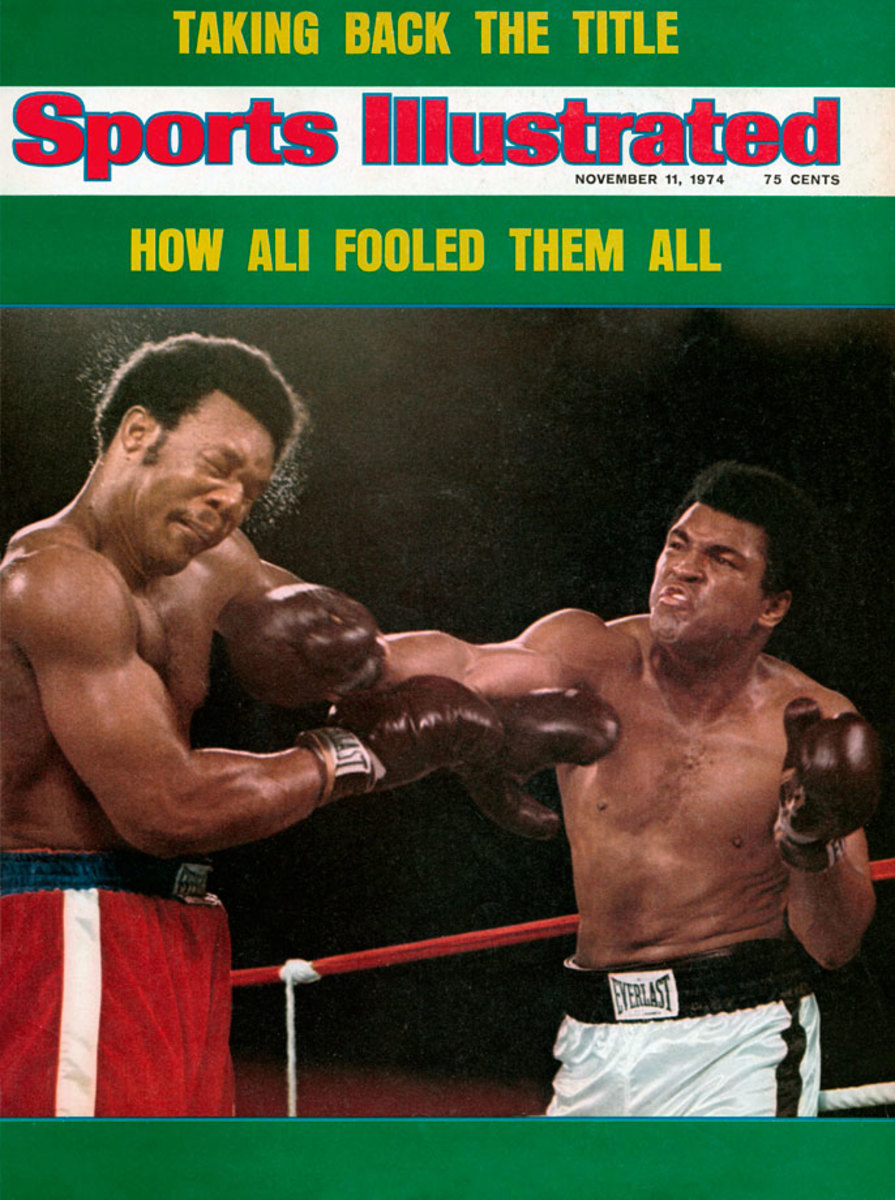

November 11, 1974

December 23, 1974

September 15, 1975

October 13, 1975

March 1, 1976

October 10, 1977

September 25, 1978

April 14, 1980

September 29, 1980

October 13, 1980

April 25, 1988

November 15, 1989

January 13, 1992

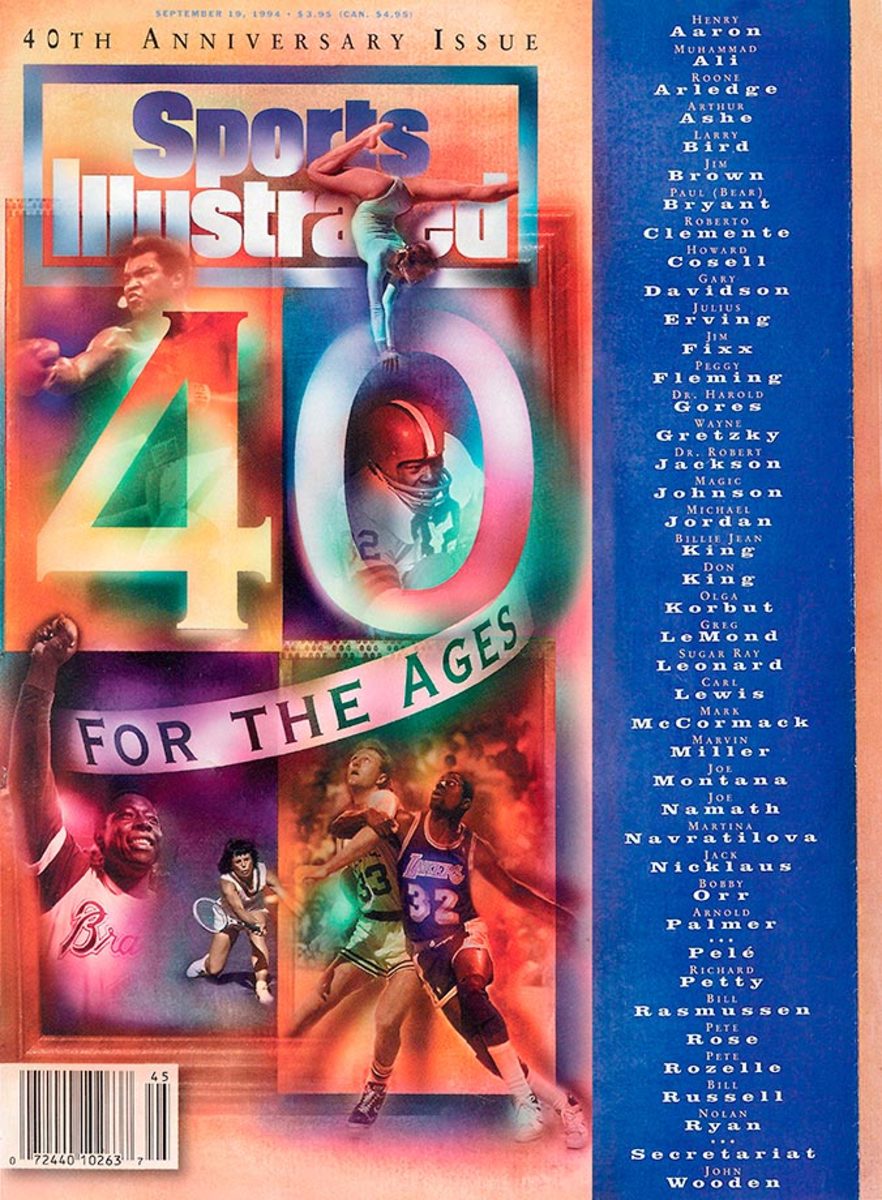

September 19, 1994

September 30, 1996

July 13, 1998

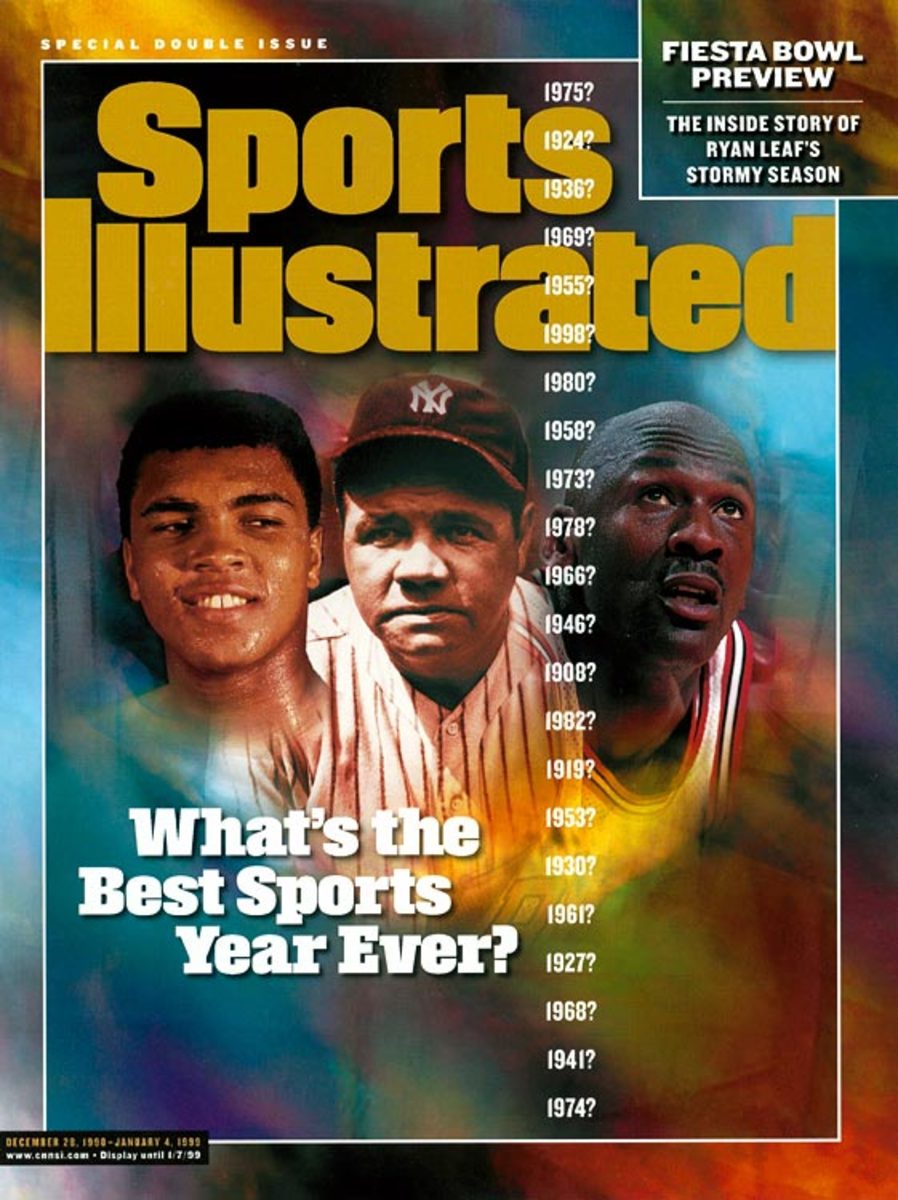

December 28, 1998

July 26, 1999

November 29, 1999

April 26, 2004

October 5, 2015

June 13, 2016